Performance and the Spiritual Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

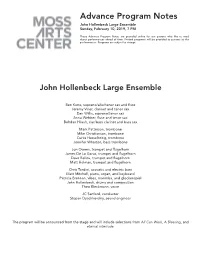

Advance Program Notes John Hollenbeck Large Ensemble Sunday, February 10, 2019, 7 PM

Advance Program Notes John Hollenbeck Large Ensemble Sunday, February 10, 2019, 7 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. John Hollenbeck Large Ensemble Ben Kono, soprano/alto/tenor sax and flute Jeremy Viner, clarinet and tenor sax Dan Willis, soprano/tenor sax Anna Webber, flute and tenor sax Bohdan Hilash, clar/bass clarinet and bass sax Mark Patterson, trombone Mike Christianson, trombone Curtis Hasselbring, trombone Jennifer Wharton, bass trombone Jon Owens, trumpet and flugelhorn James De La Garza, trumpet and flugelhorn Dave Ballou, trumpet and flugelhorn Matt Holman, trumpet and flugelhorn Chris Tordini, acoustic and electric bass Matt Mitchell, piano, organ, and keyboard Patricia Brennan, vibes, marimba, and glockenspiel John Hollenbeck, drums and composition Theo Bleckmann, voice JC Sanford, conductor Stepan Dyachkovskiy, sound engineer The program will be announced from the stage and will include selections from All Can Work, A Blessing, and eternal interlude. Program Notes From the Liner Notes of All Can Work After pondering many titles for this record, I realized All Can Work epitomizes the flexible, optimistic resolve that is needed by everyone involved to do a record like this. This phrase, “All Can Work,” and the lyrics in this title track are taken directly from the emails in my inbox from Laurie Frink, our beloved trumpeter, whom we lost in 2013. When I first moved to NYC and started playing with and hearing big bands, Laurie was a special thread that wove through them all—it seemed like she played in every band I saw! A master of the short, perfect email reply, Laurie was also the consummate team player, the type of personality that is profoundly needed in a large ensemble. -

MEREDITH MONK and ANN HAMILTON: Aaron Copland Fund for Music, Inc

The House Foundation for the Arts, Inc. | 260 West Broadway, Suite 2, New York, NY 10013 | Tel: 212.904.1330 Fax: 212.904.1305 | Email: [email protected] Web: www.meredithmonk.org Incorporated in 1971, The House Foundation for the Arts provides production and management services for Meredith Monk, Meredith Monk & Vocal Ensemble, and The House Company. Meredith Monk, Artistic Director • Olivia Georgia, Executive Director • Amanda Cooper, Company Manager • Melissa Sandor, Development Consultant • Jahna Balk, Development Associate • Peter Sciscioli, Assistant Manager • Jeremy Thal, Bookkeeper Press representative: Ellen Jacobs Associates | Tel: 212.245.5100 • Fax: 212.397.1102 Exclusive U.S. Tour Representation: Rena Shagan Associates, Inc. | Tel: 212.873.9700 • Fax: 212.873.1708 • www.shaganarts.com International Booking: Thérèse Barbanel, Artsceniques | [email protected] impermanence(recorded on ECM New Series) and other Meredith Monk & Vocal Ensemble albums are available at www.meredithmonk.org MEREDITH MONK/The House Foundation for the Arts Board of Trustees: Linda Golding, Chair and President • Meredith Monk, Artistic Director • Arbie R. Thalacker, Treasurer • Linda R. Safran • Haruno Arai, Secretary • Barbara G. Sahlman • Cathy Appel • Carol Schuster • Robert Grimm • Gail Sinai • Sali Ann Kriegsman • Frederieke Sanders Taylor • Micki Wesson, President Emerita MEREDITH MONK/The House Foundation for the Arts is made possible, in part, with public and private funds from: MEREDITH MONK AND ANN HAMILTON: Aaron Copland Fund for -

Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth-Century America

CRUMP, MELANIE AUSTIN. D.M.A. When Words Are Not Enough: Tracing the Development of Extended Vocal Techniques in Twentieth-Century America. (2008) Directed by Mr. David Holley, 93 pp. Although multiple books and articles expound upon the musical culture and progress of American classical, popular and folk music in the United States, there are no publications that investigate the development of extended vocal techniques (EVTs) throughout twentieth-century American music. Scholarly interest in the contemporary music scene of the United States abounds, but few sources provide information on the exploitation of the human voice for its unique sonic capabilities. This document seeks to establish links and connections between musical trends, major artistic movements, and the global politics that shaped Western art music, with those composers utilizing EVTs in the United States, for the purpose of generating a clearer musicological picture of EVTs as a practice of twentieth-century vocal music. As demonstrated in the connecting of musicological dots found in primary and secondary historical documents, composer and performer studies, and musical scores, the study explores the history of extended vocal techniques and the culture in which they flourished. WHEN WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH: TRACING THE DEVELOPMENT OF EXTENDED VOCAL TECHNIQUES IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICA by Melanie Austin Crump A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Greensboro 2008 Approved by ___________________________________ Committee Chair To Dr. Robert Wells, Mr. Randall Outland and my husband, Scott Watson Crump ii APPROVAL PAGE This dissertation has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The School of Music at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

A. Mihalyi: Meredith Monkl, WAM Casopis, Recenzije, Glazba, Classical

MAGIJA VOKALA MEREDITH MONK Aleksandar Mihalyi Ako bi smo odabrali kreativno uspješnu i jedinstvenu skladateljicu i vokalisticu temeljem uspješnosti njezinog dosadašnjeg djelovanja te glasovnih mogućnosti koje izmiču uobičajenim klasifikacijama, onda bi se Meredith Jane Monk nametnula kao prvi izbor. Dodatni povod je i obilježavanje njezinog 70. rođendana ove godine – rođena je 1942. godine u New Yorku, SAD. Njezina pozicija vodeće umjetnice u američkoj avangardnoj glazbi traje od Karijeru je započela kasnih šezdesetih kao plesačica i koreograf kada je samih početaka minimalizma, a već i tada je imala izdvojenu poziciju jer je izučila umijeće poniranja do esencijalne ekspresivnosti pokretom, te nedugo vokalnu tehniku temeljila na istočnjačkim tradicijama (tzv. ekstenizirani glas zatim i glasom prije nego riječima. Monk u ovom kontekstu ističe da se – ponajprije upotrebom posebnih tehnika disanja) te u ponavljanju kratkih riječima štitimo od direktnog iskustva – tijelo treba pustiti da se fraza sličnim mantri (što su činili i ostali minimalisti). Na tu njenu izdvojenu izražava/reagira glasom (vokalizama) i pokretom. Potom, u vrijeme poziciju ponajviše je utjecalo njezino rano pohađanje škole euritmije koje tolerantne klime za diletantizam kada otkriva u sebi: „.. snažniji kreativni joj je potom i usmjerilo karijeru, odnosno interese ka povezivanju glazbe sa od interpretativnog impulsa“, ona započinje i svoju glazbenu karijeru kao pokretom s ciljem da glazbi scenom i koreografijom doda mitsko i povijesno pjevačica (inače ima izniman lirski sopran širokog raspona) i skladateljica, tumačenje. No, teško se kod nje ne može govoriti o eklekticizmu budući da kompletirajući tako autorstvo svojim scenskim djelima, koja se, uz neke Monk ponajprije asimilira ono što drži potrebnim za tehnički aspekt njezinih ograde, mogu svrstati u glazbeni teatar. -

Influencersnfluencers

Professionals MA 30 The of the year IInfluencersnfluencers december 2015 1. GEOFFREY JOHN DAVIES on the cover Founder and CEO The Violin Channel 2. LEILA GETZ 4 Founder and Artistic Director 3 Vancouver Recital Society 1 5 3. JORDAN PEIMER Executive Director ArtPower!, University of CA, San Diego 2 4. MICHAEL HEASTON 10 11 Director of the Domingo-Cafritz Young 6 7 9 Artist Program & Adviser to the Artistic Director Washington National Opera Associate Artistic Director Glimmerglass Festival 15 8 5. AMIT PELED 16 Cellist and Professor Peabody Conservatory 12 6. YEHUDA GILAD 17 Music Director, The Colburn Orchestra The Colburn School 13 Professor of Clarinet 23 Colburn and USC Thornton School of Music 14 7. ROCÍO MOLINA 20 Flamenco Dance Artist 22 24 8. FRANCISCO J. NÚÑEZ 19 21 Founder and Artistic Director 18 Young People’s Chorus of New York City 26 25 9. JON LIMBACHER Managing Director and President St. Paul Chamber Orchestra 28 10. CHERYL MENDELSON Chief Operating Officer 27 Harris Theater for Music and Dance, Chicago 30 11. MEI-ANN CHEN 29 Music Director Chicago Sinfonietta and 18. UTH ELT Memphis Symphony Orchestra R F Founder and President 24. AFA SADYKHLY DWORKIN San Francisco Performances President and Artistic Director 12. DAVID KATZ Sphinx Organization Founder and Chief Judge 19. HARLOTTE EE The American Prize C L President and Founder 25. DR. TIM LAUTZENHEISER Primo Artists Vice President of Education 13. JONATHAN HERMAN Conn-Selmer Executive Director 20. OIS EITZES National Guild for Community Arts Education L R Director of Arts and Cultural Programming 26. JANET COWPERTHWAITE WABE-FM, Atlanta Managing Director 14. -

Battles Around New Music in New York in the Seventies

Presenting the New: Battles around New Music in New York in the Seventies A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David Grayson, Adviser December 2012 © Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher 2012 i Acknowledgements One of the best things about reaching the end of this process is the opportunity to publicly thank the people who have helped to make it happen. More than any other individual, thanks must go to my wife, who has had to put up with more of my rambling than anybody, and has graciously given me half of every weekend for the last several years to keep working. Thank you, too, to my adviser, David Grayson, whose steady support in a shifting institutional environment has been invaluable. To the rest of my committee: Sumanth Gopinath, Kelley Harness, and Richard Leppert, for their advice and willingness to jump back in on this project after every life-inflicted gap. Thanks also to my mother and to my kids, for different reasons. Thanks to the staff at the New York Public Library (the one on 5th Ave. with the lions) for helping me track down the SoHo Weekly News microfilm when it had apparently vanished, and to the professional staff at the New York Public Library for Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, and to the Fales Special Collections staff at Bobst Library at New York University. Special thanks to the much smaller archival operation at the Kitchen, where I was assisted at various times by John Migliore and Samara Davis. -

NEW MUSIC COMPOSITION for LIVE PEFORMANCE and INTERACTIVE MULTIMEDIA DOCTOR of CREATIVE ARTS from by THOMAS A. FITZGERALD Bmus

NEW MUSIC COMPOSITION FOR LIVE PEFORMANCE AND INTERACTIVE MULTIMEDIA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF CREATIVE ARTS from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by THOMAS A. FITZGERALD BMus(Hons), MMus(Melb) FACULTY of CREATIVE ARTS 2004 Thesis Certification CERTIFICATION I, Thomas A. Fitzgerald, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Creative Arts, in the Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Thomas A. Fitzgerald 23rd October 2004 Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge the invaluable support of my Supervisors, Professor Stephen Ingham and Dr. Houston Dunleavy, whose insight and wisdom illuminated my journey in this creative research project. In addition, their patience and resourcefulness remained constant throughout these demanding four years. I also received considerable technical and administrative assistance from the staff at the Creative Arts Department, especially Des Fitzsimons, Alaister Davies, and Olena Cullen. The U.O.W. Library and Research Student Centre staff at U.O.W., led by Julie King, were consistently resourceful. This research was made possible through a University of Wollongong Post Graduate Award, and I remain deeply appreciative of this financial assistance. My associate research collaborative artists, especially Lycia Danielle Trouton, and as well, Elizabeth Cameron-Dalman, Hilary Rhodes, and John Bennett, provided invaluable insight and creative inspiration. Finally, I am appreciative of the emotional and personal support of my own family-Lindy, Jessica, Alice, as well as my parents and siblings. -

THE ARMITAGE BALLET • MEREDITH MONK an ARTIST and HER MUSIC BROOKLYN ACADEMY of MUSIC Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Executive Producer

~'f& •. & OF MUSIC THE ARMITAGE BALLET • MEREDITH MONK AN ARTIST AND HER MUSIC BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Executive Producer BAM Carey Playhouse November 20-22, 1987 presents MEREDITH MONK AN ARTIST AND HER MUSIC with ALLISON EASTER WAYNE HANKIN ROBERTEEN NAAZ HOSSEINI CHING GONZALEZ NICKY PARAISO ANDREA GOODMAN NURIT TILLES and guest artist BOBBY McFERRIN Music Composed by Lighting Designed by MEREDITH MONK· TONY GIOVANNETTI Costumes Designed by 1echnical Director Stage Manager YOSHIO YABARA DAVID MooDEY PEGGY GOULD Sound 1echnician Costume Assistant DAVE MESCHTER ANNEMARIE HOLLANDER Meredith Monk: An Artist And Her Music is presented in association with THE HOUSE FOUNDATION FOR THE AIUS, INC. The music events of the NEXT WAVE Festival are made possible, in part, with a grant from the MARY FLAGLER CARY CHARITABLE TRUST BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC E i ;II-----,FEIS;~AL·1 SPONSORED BY PHILIP MORRIS COMPANIES INC. The 1987 NEXT WAVE Festival is sponsored by PllILIPMORRISCOMPANIES INC. The NEXT WAVE Production and Touring Fund and Festival are supported by: the NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FORTIlE AKfS, TIlEROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION, TIlEFORD FOUNDATION, TIlE ELEANOR NAYWR DANA CHARITABLE TRUST, PEW CHARITABLE TRUSTS, the BOOI'II FERRIS FOUNDATION, TIlE IlENRYLuCEFOUNDATlON, INC., theAT&if FOUNDATION, TIlEHOWARD GILMAN FOUNDATION, TIlEWILLIAM AND FIDRA HEWLEITFOUNDATlON, theMARY FLAGLER CARY CHARITAl'LETRUST, TllEHINDUJAFOUNDATlON, TIlEEDUCATIONAL FOUNDATION OFAMERICA, the MORGAN GUARANTY TRUST coMPANY, ROBERI' w. WILSON, 'DIEREFJ)FOUNDATION INC., theEMMA A. SIIEAFERCHARITABLE TRUST, SCHLUMBERGER, YVES SAINT LAURENT INTERNATIONAL, andtheNEW lQRK STATE COUNCD.. ON TIlE AR1K Additional funds for the NEXT WAVE Festival are provided by: TIlEBEST PRODUcm FOUNDATION, C~OLA ENTEKI'AINMENT, INC., MEET TIlECOMPOSER, INC., the CIGNA CORPORATION, TIlEWILLIAM AND MARY GREVE FOUNDATION, INC., the SAMUEL I. -

OOT 2020 Packet 10.Pdf

OOT 2020: [The Search for a Middle Clue] Written and edited by George Charlson, Nick Clanchy, Oli Clarke, Laura Cooper, Daniel Dalland, Alexander Gunasekera, Alexander Hardwick, Claire Jones, Elisabeth Le Maistre, Matthew Lloyd, Lalit Maharjan, Alexander Peplow, Barney Pite, Jacob Robertson, Siân Round, Jeremy Sontchi, and Leonie Woodland. THE ANSWER TO THE LAST TOSS-UP SHOULD HAVE BEEN: Henry Packet 10 Toss-ups: 1. Rana Sweid and Eyal Goldman attend this tournament in the experimental film Strangers. The manager of one team in this tournament said after one match that ‘Jesus Christ may be able to turn the other cheek, but [one player] isn't Jesus Christ’. Another player was called ‘the most hated man in Trinidad and Tobago’ after pulling Brent Sancho’s dreadlocks before scoring a header for England in this tournament. Valentin Ivanov handed out four red cards and sixteen yellows during a match in this tournament between Portugal and the Netherlands called ‘the Battle of Nuremberg’. David Trezeguet missed the only penalty in its final. Zinedine Zidane was sent off for head-butting a player in the final of, for 10 points, what football tournament hosted by Germany? ANSWER: 2006 FIFA World Cup [prompt on World Cup with ‘which year?’] <GDC> 2. A hypothesis named for a thinker from this country claims that scientific advancement is mainly the result of the work of mediocre researchers. One thinker from this country tried to resolve the conflict between experience and reason by developing the concept of ‘ratio-vitalism’. That thinker from this country argued for a life lived nobly as opposed to as a ‘mass-man’ in their work The Revolt of the Masses. -

Meredith Monk / the House Foundation for the Arts

Meredith Monk / Meredith Monk & Vocal Ensemble 2015-2016 COMPANY INFORMATION PIECE: On Behalf of Nature A new music theater work by Meredith Monk NUMBER OF PEOPLE: 8 performers and 5-6 staff/crew - Total 13-14 SET UP: Two days before first performance STAGE SIZE: Proscenium opening 44’ wide; 16’ wing space left and right; 66’ from plaster line to rear theatre wall including on-stage crossover; Orchestra pit with lifts or platforms for leveling. RECENT VENUES: On Behalf of Nature premiered January 18th, 2013 at Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA with additional performances at the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center at the University of Maryland, the Edinburgh International Festival, Krannert Center at the University of Illinois, and this season at the Brooklyn Academy of Music and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION: For her newest music-theater work, Meredith Monk offers a poetic meditation on our intimate connection to nature and the fragility of its ecology. Within this world, Monk evokes the Buddhist notion of the existence of different realm categories—the idea of joining heaven and earth by way of human beings. Drawing additional inspiration from writers and researchers who have sounded the alarm on the precarious state of our global ecology, Monk and her acclaimed Vocal Ensemble create a liminal space where human, natural and spiritual elements are woven into a delicate whole, illuminating the interconnection and interdependency of us all. The Vocal Ensemble consists of multitalented singers / performers / instrumentalists Sidney Chen, Ellen Fisher, Katie Geissinger, Bohdan Hilash, John Hollenbeck, Bruce Rameker and Allison Sniffin. -

To the Fullest: Organicism and Becoming in Julius Eastman's Evil

Title Page To the Fullest: Organicism and Becoming in Julius Eastman’s Evil N****r (1979) by Jeffrey Weston BA, Luther College, 2009 MM, Bowling Green State University, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2020 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jeffrey Weston It was defended on April 8, 2020 and approved by Jim Cassaro, MM, MLS, Department of Music Autumn Womack, PhD, Department of English (Princeton University) Amy Williams, PhD, Department of Music Dissertation Co-Director: Michael Heller, PhD, Department of Music Dissertation Co-Director: Mathew Rosenblum, PhD, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Jeffrey Weston 2020 iii Abstract To the Fullest: Organicism and Becoming in Julius Eastman’s Evil N****r (1979) Jeffrey Weston, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2020 Julius Eastman (1940-1990) shone brightly as a composer and performer in the American avant-garde of the late 1970s- ‘80s. He was highly visible as an incendiary queer black musician in the European-American tradition of classical music. However, at the end of his life and certainly after his death, his legacy became obscured through a myriad of circumstances. The musical language contained within Julius Eastman’s middle-period work from 1976-1981 is intentionally vague and non- prescriptive in ways that parallel his lived experience as an actor of mediated cultural visibility. The visual difficulty of deciphering Eastman’s written scores compounds with the sonic difference in the works as performed to further ambiguity. -

Canto Difónico

SELECCIÓN DE TEXTOS INDICE ARTISTAS Y PERFORMERS David Moss y su posibilidades de la voz 4 Ensambla Ritornelo 7 Meredith Monk: El arte en las fronteras 8 ¿Qué es la música? Un Viaje Maravilloso: Bobby McFerrin de Angel Vargas 13 Tribe of Sound 15 TÉCNICAS VOCALES CONTEMPORÁNEAS NO CONVENCIONALES Scat Singing (Texto en Inglés) 16 Louis Armstrong 16 Beatbox (Texto en inglés) 17 Beardyman (Texto en Inglés) 18 Rahzel 18 CANTOS TRADICIONALES TranQuang hai devant un spectre de chant diphonique (Texto en francés) 20 Dhrupad (Texto en Inglés) 23 The origin and Grammar of Dhrupad ((Texto en inglés) 23 Mapuche 27 “Escuchando la voz de los pueblos indígenas…” 29 Canto difónico: todas las voces en una 35 Música Tibetana: el sonido que llega del techo del mundo 37 Los cantantes de garganta de Tuva 41 La Cábala 45 Los tonos de la octava cósmica de Hans Cousto 48 Maria Sabina 50 POESÍA SONORA Ubuweb: Ethnopoetics-Section Curated by Jerome Rothenberg (Texto en Inglés) 64 Poesia Fonética (las avanguardias históricas) 65 La poesía experimental en America Latina de Clemente Padín 69 Poesía Sonora 72 Poetas Sonoros 72 ARTE RADIOFÓNICO Radio (Texto en Francés) 76 Radiotopia on site (Texto en Inglés) 76 Radia Futurista 77 Lear- Laboratorio Experimental de arte Radiofónico 79 Radio Arte Fluxus [extracto] 80 Arte Radiofónico: Bibliografía recomendada 83 1-ARTISTAS Y PERFORMERS DAVID MOSS Y SU MANIFIESTO DE LAS POSIBILI- DADES DE LA VOZ www.radioeducacion.edu.mx www.bienalderadio.com COMUNICADO DE PRENSA 6 / MAYO DE 2006 “Durante más de 100 mil años, la voz humana ha sido una de las primigenias fuentes de emoción, comuni- cación, información y trascendencia.