Chisholm-Batten, E, the Forest Trees of Somerset, Part II, Volume 36

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feral Wild Boar: Species Review.' Quarterly Journal of Forestry, 110 (3): 195-203

Malins, M. (2016) 'Feral wild boar: species review.' Quarterly Journal of Forestry, 110 (3): 195-203. Official website URL: http://www.rfs.org.uk/about/publications/quarterly-journal-of-forestry/ ResearchSPAce http://researchspace.bathspa.ac.uk/ This version is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite using the reference above. Your access and use of this document is based on your acceptance of the ResearchSPAce Metadata and Data Policies, as well as applicable law:- https://researchspace.bathspa.ac.uk/policies.html Unless you accept the terms of these Policies in full, you do not have permission to download this document. This cover sheet may not be removed from the document. Please scroll down to view the document. 160701 Jul 2016 QJF_Layout 1 27/06/2016 11:34 Page 195 Features Feral Wild Boar Species review Mark Malins looks at the impact and implications of the increasing population of wild boar at loose in the countryside. ild boar (Sus scrofa) are regarded as an Forests in Surrey, but meeting with local opposition, were indigenous species in the United Kingdom with soon destroyed. Wtheir place in the native guild defined as having Key factors in the demise of wild boar were considered to been present at the end of the last Ice Age. Pigs as a species be physical removal through hunting and direct competition group have a long history of association with man, both as from domestic stock, such as in the Dean where right of wild hunted quarry but also much as domesticated animals with links traced back to migrating Mesolithic hunter-gatherer tribes in Germany 6,000-8,000 B.P. -

Hamish Graham

14 French History and Civilization “Seeking Information on Who was Responsible”: Policing the Woodlands of Old Regime France Hamish Graham In a sense Pierre Robert was simply unlucky. Robert was a forest guard from Saint-Macaire, a small town on the right bank of the Garonne about twelve leagues (or nearly fifty kilometers) upstream from the regional capital of Bordeaux. In 1780 he was convicted of corruption and dismissed from the royal forest service, the Eaux et Forêts. According to lengthy testimonies compiled by his superiors, Robert had identified breaches by local landowners of the regulations about woodland exploitation set down in the 1669 Ordonnance des Eaux et Forêts. He then demanded payment directly from the offenders. The forestry officials took a dim view of these charges, and the full force of the law was brought to bear: Robert’s case went as far as the “sovereign court” of the Parlement in Bordeaux.1 Michel Marchier was also an eighteenth-century forest guard in south-western France whose actions could be considered corrupt: like Robert, Marchier was accused of soliciting a bribe from a known forest offender. Unlike Robert, however, Marchier was not subjected to judicial proceedings, and he was certainly not dismissed. His case was not even reported to the regional headquarters of the Eaux et Forêts in Bordeaux. Instead Marchier’s punishment was extra-judicial: he was publicly denounced in a local market-place, and then beaten up by his target’s son.2 There are several possible ways we could explain the different ways in which these two matters were handled, perhaps by focusing on issues of individual personality or the seriousness of the men’s offenses. -

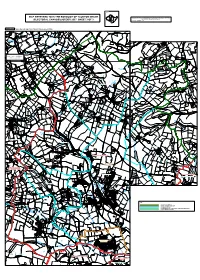

MAP REFERRED to in the BOROUGH of TAUNTON DEANE Created by the Ordnance Survey Boundaries Section, Southampton, SO16 4GU

Sheet 3 3 MAP REFERRED TO IN THE BOROUGH OF TAUNTON DEANE Created by the Ordnance Survey Boundaries Section, Southampton, SO16 4GU. 2 1 Tel: 023 8030 5092 Fax: 023 8079 2035 (ELECTORAL CHANGES) ORDER 2007 SHEET 3 OF 3 © Crown Copyright 2007 SHEET 3, MAP 3 Taunton Deane Borough. Parish Wards in Bishop's Lydeard Parish E N A L E AN D L L OO O P O D W UN RO Roebuck Farm Wes t So mer set Rai lway A 3 5 8 Ashfield Farm Aisholt Wood Quarry L (dis) IL H E E R T H C E E B Hawkridge Common All Saints' Church E F Aisholt AN L L A TE X Triscombe A P Triscombe Quarry Higher Aisholt G O Quarries K O Farm C (Stone) (disused) BU L OE H I R L L Quarry (dis) Flaxpool Roebuck Gate Farm Quarry (dis) Scale : 1cm = 0.1000 km Quarry (dis) Grid interval 1km Heathfield Farm Luxborough Farm Durborough Lower Aisholt Farm Caravan G Site O O D 'S L Triscombe A N W House Quarry E e Luxborough s t (dis) S A Farm o 3 m 5 8 e Quarry r s e (dis) t R a i l w a y B Quarry O A (dis) R P A T H L A N E G ood R E E N 'S Smokeham R H OCK LANE IL Farm L L HIL AK Lower Merridge D O OA BR Rock Farm ANE HAM L SMOKE E D N Crowcombe e A L f Heathfield K Station C O R H OL FO Bishpool RD LA Farm NE N EW Rich's Holford RO AD WEST BAGBOROUGH CP Courtway L L I H S E O H f S H e E OL S FOR D D L R AN E E O N Lambridge H A L Farm E Crowcombe Heathfield L E E R N H N T E K Quarry West Bagborough Kenley (dis) Farm Cricket Ground BIRCHES CORNER E AN Quarry 'S L RD Quarry (dis) FO BIN (dis) D Quarry e f (dis) Tilbury Park Football Pitch Coursley W e s t S Treble's Holford o m e E Quarry L -

Northern Devon in the Domesday Book

NORTHERN DEVON IN THE DOMESDAY BOOK INTRODUCTION The existence of the Domesday Book has been a source of national pride since the first antiquarians started to write about it perhaps four hundred years ago. However, it was not really studied until the late nineteenth century when the legal historian, F W Maitland, showed how one could begin to understand English society at around the time of the Norman Conquest through a close reading and analysis of the Domesday Book (Maitland 1897, 1987). The Victoria County Histories from the early part of the twentieth century took on the task of county-wide analysis, although the series as a whole ran out of momentum long before many counties, Devon included, had been covered. Systematic analysis of the data within the Domesday Book was undertaken by H C Darby of University College London and Cambridge University, assisted by a research team during the 1950s and 1960s. Darby(1953), in a classic paper on the methodology of historical geography, suggested that two great fixed dates for English rural history were 1086, with Domesday Book, and circa 1840, when there was one of the first more comprehensive censuses and the detailed listings of land-use and land ownership in the Tithe Survey of 1836-1846. The anniversary of Domesday Book in 1986 saw a further flurry of research into what Domesday Book really was, what it meant at the time and how it was produced. It might be a slight over-statement but in the early-1980s there was a clear consensus about Domesday Book and its purpose but since then questions have been raised and although signs of a new shared understanding can be again be seen, it seems unlikely that Domesday Book will ever again be taken as self-evident. -

Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England Shawn Hale Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hale, Shawn, "Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England" (2016). Masters Theses. 2418. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2418 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� EASTERNILLINOIS UNIVERSITY " Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

Somersetshire

400 TAUNTON. SOMERSETSHIRE. [ KELLY's Halse, Ham, Hatch Beauchamp, Heathfield, Henlade, Prince Albert's Somersetshire Light Infantry Regiment, Huish Cha.mpflower, Kingston, Langford, Lillesdon, 4th Battalion (2nd Somerset Militia); head quarters, Lydeard St. Lawrence, Milverton Na.ilesbourne, Barracks, Mount street; Hon. Col. W. Long, command Norton Fitzwarren, Newport, North Curry, Orchard ing; Hon. Lt.-Col. E. H. Llewellyn & C. S. Shepherd Portman, Otterford, Pitminster, Quantock, Ra.ddington, D.S.O. majors; Capt. E. A. B. Warry, instructor of Rowbarton, Ruishton, Staplegrove, Staple Fitzpaine, musketry; Capt. W. H. Lovett, adjutant; Lieut. li. Staplehay, Stoke St. Mary, Taunton, with Haydon, Powis, quartermaster Holway & Shoreditch, Thornfalcon, Thurlbear, Tul land, Trull, West Bagborough, West Hatch, West YEOMANRY CAVALRY. Monkton, Wilton, Wiveliscombe & Wrantage 4th Yeomanry Brigade. The Court has also Bankruptcy Jurisdiction & includes Brigade Office, Church square. for Bankruptcy purposes the following courts : Taunton, Officer Commanding Brigade, the Senior Commanding Williton, Chard & Wellington; George Philpott, Ham· met street, Taunton, official receiver Officer Certified Bailiffs under the " Law of Distress Amend Brigade Adjutant, Capt. Wilfred Edward Russell Collis West Somerset; depot, II Church square; Lieut.-Col. ment Act, 1888" : William James Villar, 10 Hammet Commanding, F. W. Forrester; H. T. Daniel, major ; street; Joseph Darby, 13 Hammet street; William Surgeon-Lieut.-Col. S. Farrant, medical officer • Waterman, 31 Paul street; Thomas David Woollen, Veterinary-Lieut. George Hill Elder M.R.C.V.S. Shire hall ; Howard Maynard, Hammet street ; John M. veterinary officer; Frederick Short, regimental sergt.- Chapman, 10 Canon street ; Horace White Goodman, • maJor 10 Hammet street; Frederick Williain Waterman, 31 B Squadron, Capt. E. -

Trull Somerset 1871 Census

1871 Census of Trull Somerset UK (Transcribed by Roy Parkhouse [email protected]) rg102367 Civil Parish ED Folio Page Schd House Address X Surname Forenames X Rel. C Sex Age X Occupation E X CHP Place of birth X Dis. W Notes abcdefghijklmnopqrst ###a ####a #### ###a ####a abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzabcd X abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwx abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwx X abcdef C S ###a X abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzabcd E X abc abcdefghijklmnopqrst X abcdef W abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzabcdefghijklmnopqr Trull 5 49 3 12 Budleigh Farm Clark William head M M 49 farmer 110 acres empl 2 labs SOM Pitminster Clark Alice wife M F 54 farmer's wife SOM Broadway Clark Thomas son U M 21 farmer's son DEV Yarcombe Clark William son U M 18 farmer's son SOM Bishops Hull Clark Edwin son U M 15 farmer's son SOM Bishops Hull Clark Charles son U M 15 farmer's son SOM Bishops Hull Clark James Daniel son U M 13 farmer's son SOM Bishops Hull Clark William father W M 75 retired farmer GLS Gloucester Pinney Mary niece U F 27 house keeper SOM Cricket St Malherbie? Trickey Ann servnt U F 13 dairymaid DEV Churchstanton 13 Budleigh Farm Braddick William Ellis head M M 62 farmer 150 acres empl 3 labs DEV Clayhidon Braddick Ann Eliza W wife M F 59 farmer's wife SOM Bickenhall Braddick Eliza Ann dau U F 19 farmer's daughter SOM Trull Braddick Jemima dau U F 17 farmer's daughter SOM Trull Braddick Laura dau U F 15 farmer's daughter SOM Trull Cozens Edward servnt U M 45 farm servant SOM Bickenhall Trickey Robert servnt U M 17 farm servant DEV Clayhidon 14 Harpers Cottage Griffin John -

Ancient Hampshire Forests and the Geological Conditions of Their Growth

40 ANCIENT HAMPSHIRE FORESTS AND THE GEOLOGICAL CONDITIONS OF THEIR GROWTH. ,; BY T. W, SHORE, F.G.S., F.C.S. If we examine the map oi Hampshire with the view of considering what its condition, probably was' at that time which represents the dawn of history, viz., just before the Roman invasion, and consider what is known of the early West Saxon settlements in the county, and of the earthworks of their Celtic predecessors, we can .scarcely fail to come to the conclusion that in pre-historic Celtic time it must have been almost one continuous forest broken only by large open areas of chalk down land, or by the sandy heaths of the Bagshot or Lower Greensand formations. On those parts of the chalk down country which have only a thin soil resting on the white chalk, no considerable wood could grow, and such natural heath and furze land as the upper Bagshot areas of the New Forest, of Aldershot, and Hartford Bridge Flats, or the sandy areas of the Lower Bagshot age, such as exists between Wellow and Bramshaw, or the equally barren heaths of the Lower Greensand age, in the neighbourhood of Bramshot and Headley, must always have been incapable of producing forest growths. The earliest traces of human settlements in this county are found in and near the river valleys, and it as certain as any matter which rests on circumstantial evidence, can be that the earliest clearances in the primaeval woods of Hampshire were on the gently sloping hill sides which help to form these valleys, and in those dry upper vales whicli are now above the permanent sources of the rivers. -

Dedicattons of Tfte Cfjutcbcs of ©Ometsetsftire. “L

DeDicattons of tfte Cfjutcbcs of ©ometsetsftire. BY THE KEY. E. H. BATES, M.A HE late Mr. W illiam Long contributed to the seventeenth “L volume of the Proceedings in 1871 a classified list of the Church Dedications given by Ecton in his Thesaurus Rerum Ecclesiasticarum, 1742. As Editor of the Bath and Wells Diocesan Kalendar my attention has been frequently drawn, from my own knowledge as well as by numerous correspon- dents, to the many errors and gaps in that list. It became plainly necessary to go behind the Thesaurus to the original sources of information. And here I may be allowed to repro- duce what I have already stated in the preface to the Kalendar for 1905. It should be clearly understood that there is no authoritative list in existence. Among the Public Becords are two works known as Pope Nicholas’ Taxatio of 1291, and the Valor Ec- clesiasticus of 27 Henry VIII (1536), containing the names of all parishes in England and Wales. These were primarily drawn up to ascertain the value of the benefices, and only in- cidentally, as in the case of towms with many churches, are the dedications added. The latter work, to which the title of V^ahr Ecclesiasticus or Liber Regis is generally given, was first printed in 1711 by J ohn Ecton. His preface contains a very interesting account of the early work of the Queen Anne’s Bounty Fund, of which he was Receiver, and of the serious state of affairs in the large towns which led to its foundation. -

Situation of Polling Stations

SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS UK Parliamentary General Election Taunton Deane Constituency Date of Election: Thursday 12 December 2019 Hours of Poll: 7:00 am to 10:00 pm Notice is hereby given that: The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Station Ranges of electoral register numbers Situation of Polling Station Number of persons entitled to vote thereat Ashbrittle Village Hall, Ashbrittle, Wellington 201 DAA - T-1 to DAA - T-179 Ash Priors Village Hall, Ash Priors, Taunton 202 DAB - T-1 to DAB - T-146 Bathealton Village Hall, Bathealton, Taunton 203 DAC - T-1 to DAC - T-141 Neroche Hall Bickenhall, New Road, Bickenhall 204 DAD - T-1 to DAD - T-81 Neroche Hall Bickenhall, New Road, Bickenhall 204 DBC - T-1 to DBC - T-126 Neroche Hall Bickenhall, New Road, Bickenhall 204 DDB - T-1 to DDB - T-146 St Peter & St Pauls Church Hall, Bishops Hull, Taunton 205 DAF - T-1 to DAF - T-1559 St Peter & St Pauls Church Hall, Bishops Hull, Taunton 206 DAF - T-1561 to DAF - T-2853 Bishops Lydeard Village Hall, Mount St, Bishops Lydeard 207 DAG - T-1173 to DAG - T-2319 Bishops Lydeard Village Hall, Mount St, Bishops Lydeard 208 DAG - T-1 to DAG - T-1172 Bishops Lydeard Village Hall, Mount St, Bishops Lydeard 208 DAH - T-1 to DAH - T-101 Bradford on Tone Village Hall, Bradford on Tone, Taunton 209 DAI - T-1 to DAI - T-554 Coronation Hall, West Yeo Road, Burrowbridge 210 DAN - T-1 to DAN - T-420 Cheddon Fitzpaine Memorial Hall, Cheddon Fitzpaine 211 DAQ - T-1 to DAQ - T-256 West Monkton Village -

ROYAL FOREST of EXMOOR: RESEARCH FRAMEWORK Exmoor National Park Historic Environment Report Series No 7 the ROYAL FOREST of EXMOOR: RESEARCH FRAMEWORK

Exmoor National Park Historic Environment Report Series No 7 THE ROYAL FOREST OF EXMOOR: RESEARCH FRAMEWORK Exmoor National Park Historic Environment Report Series No 7 THE ROYAL FOREST OF EXMOOR: RESEARCH FRAMEWORK Exmoor National Park Historic Environment Report Series Author: Faye Balmond Design: Pete Rae March 2012 This report series includes interim reports, policy documents and other information relating to the historic environment of Exmoor National Park. Further hard copies of this report can be obtained from the Exmoor National Park Historic Environment Record: Exmoor House, Dulverton, Somerset. TA22 9HL email [email protected], 01398 322273 FRONT COVER: Simonsbath Tower ©Exmoor National Park Authority CONTENTS Page SUMMARY . 1 INTRODUCTION, BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES . 1 RESEARCH FRAMEWORK . 3 THE ROYAL FOREST OF EXMOOR (ORIGINS – 1818) . 6 THE RECLAMATION OF EXMOOR FOREST (1818 – 1897) . 8 20TH CENTURY . 11 SOCIAL HISTORY AND OTHER THEMES . 11 DISSEMINATION . 12 REVIEW AND EVALUATION . 13 BILBLIOGRAPHY . 13 THE ROYAL FOREST OF EXMOOR: RESEARCH FRAMEWORK SUMMARY This document sets out the research priorities for the historic environment in the former Royal Forest of Exmoor. The priorities it lists were identified by those with an active interest in this area of Exmoor at a seminar at Ashwick in March 2012. INTRODUCTION, BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES A research framework for the former Royal Forest of Exmoor was proposed in an attempt to direct research and address the inability to answer with any degree of certainty some of the most basic questions related to the historical use and operation of this area of Exmoor National Park. The Exmoor Moorland Landscape Partnership Scheme (EMLPS) provided an opportunity to promote further research into the former Royal Forest of Exmoor, with funding available through the ‘Treeless Forest’ project. -

Village Newsletter

Lydeard St Lawrence & Tolland Village Newsletter April 2020 Editorial Well, what an odd month this has been. How quickly our lives have changed in the past couple of weeks and how good to see our villages coming together to help our communities. We have all been inundated with information recently and I know I have been sending out copious emails adding to those you may also be getting from elsewhere. But information is good and I believe it is better to see something twice than not at all. On a positive note, my call for an old second-hand bike, (remember that email from two weeks ago?), had a very positive response and an old bike has been passed on to a new, delighted owner. Below I have included a number of bits of information to do with our current situation together with a couple of non Corona things. Stay safe everyone, keep smiling and most of all if you need anything at all, ask. Liz Message from Revd. Maureen I am here for everyone in our village - whether they go to church or not - and am holding everyone in my prayers and for a good outcome. However, because of my age I am obliged to stay in the house and am very sad that there is no worship happening in our church building. However the church is not about buildings but about people, and in our concern for one another we are showing our love and care and, in a way, being church. We don't need to kneel down and put our hands together and close our eyes to pray.