Jointness and the Norwegian Campaign, 1940 Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Permanently Neutral State in the Security Council Heribert Franz Koeck

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Cornell Law Library Cornell International Law Journal Volume 6 Article 2 Issue 2 May 1973 A Permanently Neutral State in the Security Council Heribert Franz Koeck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Koeck, Heribert Franz (1973) "A Permanently Neutral State in the Security Council," Cornell International Law Journal: Vol. 6: Iss. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj/vol6/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell International Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Permanently Neutral State in the Security Council HERIBERT FRANZ KOECK* On October 20, 1972, the Republic of Austria was elected, by the General Assembly of the United Nations, a non-permanent member of the Security Council.' This was the first time that a permanently neu- tral state had obtained a seat in the Council, which, since the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice on the Competence of the General Assembly for the Admission of a State to the United Na- tions,2 must be considered the leading political organ of the United Nations. This recent step in the development of the United Nations position towards neutrality was certainly not foreseen by the founding fathers of the Charter. -

Telling the Story of the Royal Navy and Its People in the 20Th & 21St

NATIONAL Telling the story of the Royal Navy and its people MUSEUM in the 20th & 21st Centuries OF THE ROYAL NAVY Storehouse 10: New Galleries Project: Exhibition Design Report JULY 2011 NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE ROYAL NAVY Telling the story of the Royal Navy and its people in the 20th & 21st Centuries Storehouse 10: New Galleries Project: Exhibition Design Report 2 EXHIBITION DESIGN REPORT Contents Contents 1.0 Executive Summary 2.0 Introduction 2.1 Vision, Goal and Mission 2.2 Strategic Context 2.3 Exhibition Objectives 3.0 Design Brief 3.1 Interpretation Strategy 3.2 Target Audiences 3.3 Learning & Participation 3.4 Exhibition Themes 3.5 Special Exhibition Gallery 3.6 Content Detail 4.0 Design Proposals 4.1 Gallery Plan 4.2 Gallery Plan: Visitor Circulation 4.3 Gallery Plan: Media Distribution 4.4 Isometric View 4.5 Finishes 5.0 The Visitor Experience 5.1 Visuals of the Gallery 5.2 Accessibility 6.0 Consultation & Participation EXHIBITION DESIGN REPORT 3 Ratings from HMS Sphinx. In the back row, second left, is Able Seaman Joseph Chidwick who first spotted 6 Africans floating on an upturned tree, after they had escaped from a slave trader on the coast. The Navy’s impact has been felt around the world, in peace as well as war. Here, the ship’s Carpenter on HMS Sphinx sets an enslaved African free following his escape from a slave trader in The slave trader following his capture by a party of Royal Marines and seamen. the Persian Gulf, 1907. 4 EXHIBITION DESIGN REPORT 1.0 Executive Summary 1.0 Executive Summary Enabling people to learn, enjoy and engage with the story of the Royal Navy and understand its impact in making the modern world. -

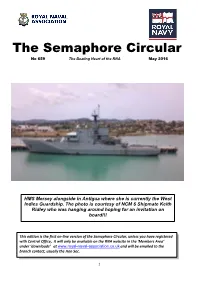

The Semaphore Circular No 659 the Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016

The Semaphore Circular No 659 The Beating Heart of the RNA May 2016 HMS Mersey alongside in Antigua where she is currently the West Indies Guardship. The photo is courtesy of NCM 6 Shipmate Keith Ridley who was hanging around hoping for an invitation on board!!! This edition is the first on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec. 1 Daily Orders 1. April Open Day 2. New Insurance Credits 3. Blonde Joke 4. Service Deferred Pensions 5. Guess Where? 6. Donations 7. HMS Raleigh Open Day 8. Finance Corner 9. RN VC Series – T/Lt Thomas Wilkinson 10. Golf Joke 11. Book Review 12. Operation Neptune – Book Review 13. Aussie Trucker and Emu Joke 14. Legion D’Honneur 15. Covenant Fund 16. Coleman/Ansvar Insurance 17. RNPLS and Yard M/Sweepers 18. Ton Class Association Film 19. What’s the difference Joke 20. Naval Interest Groups Escorted Tours 21. RNRMC Donation 22. B of J - Paterdale 23. Smallie Joke 24. Supporting Seafarers Day Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Crossed the Bar – Celebrating a life well lived RNA Benefits Page Shortcast Swinging the Lamp Forms Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General -

Resistance Rising: Fighting the Shadow War Against the Germans

Activity: Resistance Rising: Fighting the Shadow War against the Germans Guiding question: What, if any, impact did the French Resistance have on the Allied invasion of France? DEVELOPED BY MATTHEW POTH Grade Level(s): 6-8, 9-12 Subject(s): Social Studies, English/Language Arts, Journalism Cemetery Connection: Rhone American Cemetery Fallen Hero Connection: Sergeant Charles R. Perry Activity: Resistance Rising: Fighting the Shadow War against the Germans 1 Overview Using primary and secondary sources and interactive maps from the American Battle Monuments Commission, stu- dents will learn about the impact of the French Resistance “Often, civilians and on the battle for France and the overall outcome of the war. members of the military in Students will critically analyze documents to learn about the non-traditional roles are overlooked when teaching ways in which the Resistance operated. Students will create World War II. To more fully a newspaper to inform the public and recruit potential mem- understand the impact and bers to the movement. scale of the war, students must hear the stories of these men and women.” Historical Context — Matthew Poth The French Resistance was a collection of French citizens who united against the German occupation. In addition to the Poth is a teacher at Park View High School German military, which controlled northern France, many in Sterling, Virginia. French people objected to the Vichy government, the govern- ment of southern France led by World War I General Marshal Philippe Pétain. The Resistance played a vital role in the Allied advancement through France. With the aid of the men and women of the Resistance, the Allies gathered accurate intelligence on the Atlantic Wall, the deployment of German troops, and the capabilities of their enemy. -

Contribution of Greece to the Victory of the Allies During Ww Ii

CONTRIBUTION OF GREECE TO THE VICTORY OF THE ALLIES DURING WW II Lt Colonel of Engineering Panayiotis Spyropoulos Historian of the History Directorate of Hellenic Army General Staff The peninsula of Greece has, since antiquity, been a point of confrontation be- tween East and West, as it constitutes an area of utmost strategic value, situated on the flanks of the main axis of operations in East-West direction and vice-versa. Who- ever occupies Greece can effortlessly with his forces harass the flanks or even the rear of troops operating along the aforementioned axis, control the sea line of com- munication from Gibraltar to Suez, and block from the west the sea route from the Black Sea to Propontis (Marmara) Sea, the Hellespont (Straits), the Aegean Sea and the Mediterranean Sea. The geo-strategic value of Greece has been dramatically enhanced during the XXth century, due to the rapid technological development of war equipment (as per the quote of sir Halford Mackinder on the «Heartland»). During the 2nd World War, Italy launched the attack against Greece, without informing its ally, Germany. Berlin was enraged by the Italian action and considered it «totally incoherent» and mistimed, because it was initiated just before wintertime, a season unsuitable for mountain operations, as well as just before the elections in the (still neutral) USA, providing Roosevelt with even more convincing arguments for go- ing to war. Moreover, it criticised the Italians refraining from any seaborne operation, a fact that facilitated the British in debarking on Crete and other islands, significant for their strategic importance; while they left them the margin to deploy in Thessalo- nica. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

The Economics of Neutrality: Spain, Sweden and Switzerland in the Second World War

The Economics of Neutrality: Spain, Sweden and Switzerland in the Second World War Eric Bernard Golson The London School of Economics and Political Science A thesis submitted to the Department of Economic History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, 15 June 2011. Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. ‐ 2 ‐ Abstract Neutrality has long been seen as impartiality in war (Grotius, 1925), and is codified as such in The Hague and Geneva Conventions. This dissertation empirically investigates the activities of three neutral states in the Second World War and determines, on a purely economic basis, these countries actually employed realist principles to ensure their survival. Neutrals maintain their independence by offering economic concessions to the belligerents to make up for their relative military weakness. Depending on their position, neutral countries can also extract concessions from the belligerents if their situation permits it. Despite their different starting places, governments and threats against them, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland provided similar types of political and economic concessions to the belligerents. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Hans Kammler, Hitler's Last Hope, in American Hands

WORKING PAPER 91 Hans Kammler, Hitler’s Last Hope, in American Hands By Frank Döbert and Rainer Karlsch, August 2019 THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann and Charles Kraus, Series Editors This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources from all sides of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. Among the activities undertaken by the Project to promote this aim are the Wilson Center's Digital Archive; a periodic Bulletin and other publications to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for historians to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; and international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars. The CWIHP Working Paper series provides a speedy publication outlet for researchers who have gained access to newly-available archives and sources related to Cold War history and would like to share their results and analysis with a broad audience of academics, journalists, policymakers, and students. CWIHP especially welcomes submissions which use archival sources from outside of the United States; offer novel interpretations of well-known episodes in Cold War history; explore understudied events, issues, and personalities important to the Cold War; or improve understanding of the Cold War’s legacies and political relevance in the present day. -

Army Co-Operation Command and Tactical Air Power Development in Britain, 1940-1943: the Role of Army Co-Operation Command in Army Air Support

ARMY CO-OPERATION COMMAND AND TACTICAL AIR POWER DEVELOPMENT IN BRITAIN, 1940-1943: THE ROLE OF ARMY CO-OPERATION COMMAND IN ARMY AIR SUPPORT By MATTHEW LEE POWELL A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham September 2013 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the impact of the developments made during the First World War and the inter-war period in tactical air support. Further to this, it will analyse how these developments led to the creation of Army Co-operation Command and affected the role it played developing army air support in Britain. Army Co-operation Command has been neglected in the literature on the Royal Air Force during the Second World War and this thesis addresses this neglect by adding to the extant knowledge on the development of tactical air support and fills a larger gap that exists in the literature on Royal Air Force Commands. Army Co-operation Command was created at the behest of the army in the wake of the Battle of France. -

1 Introduction

Notes 1 Introduction 1. Donald Macintyre, Narvik (London: Evans, 1959), p. 15. 2. See Olav Riste, The Neutral Ally: Norway’s Relations with Belligerent Powers in the First World War (London: Allen and Unwin, 1965). 3. Reflections of the C-in-C Navy on the Outbreak of War, 3 September 1939, The Fuehrer Conferences on Naval Affairs, 1939–45 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1990), pp. 37–38. 4. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 10 October 1939, in ibid. p. 47. 5. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 8 December 1939, Minutes of a Conference with Herr Hauglin and Herr Quisling on 11 December 1939 and Report of the C-in-C Navy, 12 December 1939 in ibid. pp. 63–67. 6. MGFA, Nichols Bohemia, n 172/14, H. W. Schmidt to Admiral Bohemia, 31 January 1955 cited by Francois Kersaudy, Norway, 1940 (London: Arrow, 1990), p. 42. 7. See Andrew Lambert, ‘Seapower 1939–40: Churchill and the Strategic Origins of the Battle of the Atlantic, Journal of Strategic Studies, vol. 17, no. 1 (1994), pp. 86–108. 8. For the importance of Swedish iron ore see Thomas Munch-Petersen, The Strategy of Phoney War (Stockholm: Militärhistoriska Förlaget, 1981). 9. Churchill, The Second World War, I, p. 463. 10. See Richard Wiggan, Hunt the Altmark (London: Hale, 1982). 11. TMI, Tome XV, Déposition de l’amiral Raeder, 17 May 1946 cited by Kersaudy, p. 44. 12. Kersaudy, p. 81. 13. Johannes Andenæs, Olav Riste and Magne Skodvin, Norway and the Second World War (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1966), p. -

Churchill, Wavell and Greece, 1941*

Robin Higham Duty, Honor and Grand Strategy: Churchill, Wavell and Greece, 1941* In our previous works, then Capt. Harold E. Raugh and I took too limited a Mediterranean view of the background of the Greek campaign of 6-26 April 19411. Far from its being Raugh’s “disastrous mistake,” I argue that General Sir Archibald Wavell’s actions fitted both traditional British practice and the general policy worked out in London. In 1986 and 1987 I argued after long and careful thought since 1967 that Wavell went to Greece as part of a loyal deception of Prime Minister Winston Churchill, whose bellicose way at war was the antithesis of Wavell’s own professionalism. Further, whereas Raugh took the narrow military view, mine was a grand-strategic approach relating ends to means. My argument here is that a restudy of the campaign in Greece of 6-27 April 1941 utilizing the Orange Leonard ULTRA messages reconfirms my thesis that going to Greece was a deception and that far from being the miserable defeat which Raugh imagined, the withdrawal was a strategic triumph in the manner of a Wellington in Spain and Portugal or of the BEF’s in France in 1940. For this Wavell deserves full credit. In this respect, then, the so-called campaign in Greece must be seen not as an ignominious retreat in the face of superior forces, but rather as a skilful, carefully planned withdrawal and ultimate evacuation. It was a successful, though materially costly, gamble. * This paper was accepted for publication in late 2005 but delayed by the Balkan Studies financial crisis.