Some German Contributions to Wisconsin Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 FINAL REPORT-NORTHSIDE PITTSBURGH-Bob Carlin

1 FINAL REPORT-NORTHSIDE PITTSBURGH-Bob Carlin-submitted November 5, 1993 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I Fieldwork Methodology 3 II Prior Research Resources 5 III Allegheny Town in General 5 A. Prologue: "Allegheny is a Delaware Indian word meaning Fair Water" B. Geography 1. Neighborhood Boundaries: Past and Present C. Settlement Patterns: Industrial and Cultural History D. The Present E. Religion F. Co mmunity Centers IV Troy Hill 10 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. German a. The Fichters 2. Czech/Bohemian D. Community Celebrations V Spring Garden/The Flats 14 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity VI Spring Hill/City View 16 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. German D. Community Celebrations VII East Allegheny 18 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. German a. Churches b. Teutonia Maennerchor 2. African Americans D. Community Celebrations E. Church Consolidation VIII North Shore 24 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Community Center: Heinz House D. Ethnicity 1. Swiss-German 2. Croatian a. St. Nicholas Croatian Roman Catholic Church b. Javor and the Croatian Fraternals 3. Polish IX Allegheny Center 31 2 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Community Center: Farmers' Market D. Ethnicity 1. Greek a. Grecian Festival/Holy Trinity Church b. Gus and Yia Yia's X Central Northside/Mexican War Streets 35 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. African Americans: Wilson's Bar BQ D. Community Celebrations XI Allegheny West 36 A. -

Heritage Matters

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HERITAGE MATTERS NEWS OF THE NATION’S DIVERSE CULTURAL HERITAGE National Museum of the American Indian Opens to Great Fanfare INSIDE THIS ISSUE The Smithsonian Institution, entrance to catch the rising sun, in honor of Private First Class Curriculum materials National Museum of the American a prism window, and a 120-foot- Lori A. Piestewa, who was the first available, p. 3 Indian (NMAI), opened its doors high atrium called the Potomac. Native American servicewoman to Conferences to the public on September 21, NMAI was designed by Jones & give her life in overseas combat. A upcoming, p. 17 2004 on the National Mall in Jones, SmithGroup in association song was performed in her honor Grant Washington, DC. The museum, with Lou Weller and the Native by Black Eagle, a drum group recipients, p. 4 which was 15 years in the making, American Design Collaborative and from the Jemez Pueblo in New National Register is the first national museum in the Polshek Partnership Architects in Mexico. Remarks were delivered nominations, p. 7 country dedicated exclusively to consultation with Native American by Lawrence M. Small, Secretary Publication Native Americans, the first to pres- communities over a four-year of the Smithsonian Institution; of note, p. 17 ent all exhibitions from a Native period. Alejandro Toledo, President of viewpoint, and the first constructed The opening day ceremonies Peru; Senators Ben Nighthorse on the National Mall since 1987. began with more than 25,000 Campbell of Colorado and Daniel More than 92,000 people visited Native Americans from more than K. -

Library and Special Collections

Swiss Center of North America Library and Special Collections Finding Aid of the HELVETIA SINGERS / SWISS SINGERS, TOLEDO, OHIO Protokoll-Buch and Programs, 1923-1937 Mss 4 Helvetia Singers / Swiss Singers, Mss 4 - 1 Mss 4 Helvetia Singers / Swiss Singers, Toledo, Ohio. Protokoll-Buch and Programs, 1923-1937. 2 folders, including one volume. Restrictions There are no restrictions on this collection. Description Handwritten in German (1923-1932) and English (1923-1937), the Protokoll-Buch records the activities, January 16, 1923-September 30, 1937, of the Helvetia Singers or as later named, the Swiss Singers, Toledo, Ohio. References to performances by separate men’s (Helvetia Männerchor or Maennerchor), women’s (Helvetia Damenchor), and mixed choirs (Helvetia Gemischterchor, formed about 1924) also appear in the Protokoll-Buch. The full title of the volume as inscribed on the title page is: “Protokoll-Buch vom Helvetia Manner und Frauen Gesang-Verein, Toledo, Ohio,” or (approximately) “Record Book of the Swiss Men’s and Women’s Singing Club, Toledo, Ohio.” The singing club began its activities as part of the Grϋtli-Verein of Toledo (or Toledo Swiss Society), formed by Swiss immigrants on May 9, 1869 as a fraternal benefit, educational, and cultural organization, later separating into the three separate choirs listed above. As indicated on the club’s website as of 2015, “its aim is to retain and preserve the culture and songs of Switzerland, to live up to the singers’ ancestors’ tenets of faith and behavior, help others, and to be good citizens.” The club has been in existence continuously since its founding and continues to perform. -

KINGSTON MAENNERCHOR and DAMENCHOR NEWS Saengerfest Edition March 2018

KINGSTON MAENNERCHOR AND DAMENCHOR NEWS Saengerfest Edition March 2018 KINGSTON PRESIDENT’S WELCOME MAENNERCHOR AND DAMENCHOR, INC. Welcome to you all. It’s amazing! We are celebrating our 150th anniversary in 2018. As part of our celebration year 37 Greenkill Avenue we will be hosting the 38th Saengerfest of the New York State Kingston, New York 12401 Saengerbund on June 9th and 10th. We look forward to having you, our members and friends, join us as we celebrate this 845-338-3763 major milestone in the life of the Maennerchor. http://www.kingstonmaennerchor anddamenchor.org In this newsletter you will find much information about the weekend’s events along with quite a bit of historic information about the singing societies participating, the venues at which events will be held and about the New York State Saengerbund itself. Our music director, Dr. Dorcinda Knauth will be directing the combined choruses in the mass chorus portion of the Saengerfest concert and our Assistant Music Director Sherry Thomas will be the accompanist. The other societies participating are from Binghamton, Buffalo, Poughkeepsie, Syracuse and Utica. Finally we encourage all of you to support us financially by taking out an ad in our Anniversary Journal. Information on ad sizes and prices are in this letter along with a form for you to use in submitting your information. Please feel free to copy the form if you wish. You may also wish to make copies of this newsletter to share with friends as a way of expanding knowledge about our society. Hildegard Edling 1897 New York State Saengerbund Inc. -

The Musical Legacy of Theodore Thomas by Joseph E

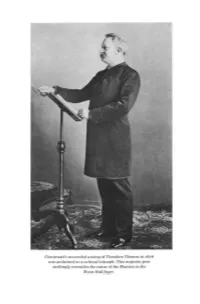

Cincinnati's successful wooing of Theodore Thomas in 1878 was acclaimed as a cultural triumph. This majestic pose strikingly resembles the statue of the Maestro in the Music Hall foyer. The Musical Legacy of Theodore Thomas by Joseph E. Holliday hen, in 1878, the officers of the newly-organized College of Music of WCincinnati secured Theodore Thomas of New York City as the school's first musical director, it was regarded as a cultural triumph. As the Albany (N. Y.) Journal said, "Cincinnati danced hornpipes over the capture of Theo- dore Thomas."1 The local newspapers proudly printed the congratulations from the press of other cities on the acquisition of this prize musical person- ality.2 As for Thomas's own reaction, he was weary of the continual tours and travel which he found necessary to keep his orchestra personnel employed, and he looked forward to "settling down."3 He also welcomed the financial security insured by an annual salary of $10,000. Thomas was highly enthusi- astic about the challenge and opportunities in Cincinnati: "its good geograph- ical location" for a music college, its considerable professional talent for a symphony orchestra, and "the first-rate summer garden business for the sum- mer employment of musicians."4 Thomas later wrote that "music had been a large part of the daily life of the Cincinnati people, and the city at that time ranked second only to New York, Boston, or Philadelphia in musical achieve- ment."5 When Thomas assumed direction of the college he was no stranger to the city. He had started his western orchestral tours in 1869, blazing a trail so frequently traversed that in music history it has been called "the Thomas Highway." Cincinnati was an important stop on this highway. -

December 2004

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers National Park Service 12-2004 Heritage Matters- December 2004 Fran P. Mainella National Park Service, [email protected] Janet Snyder Matthews National Park Service John Robbins National Park Service, [email protected] Antoinette J. Lee National Park Service, [email protected] Brian D. Joyner National Park Service, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark Mainella, Fran P.; Snyder Matthews, Janet; Robbins, John; Lee, Antoinette J.; and Joyner, Brian D., "Heritage Matters- December 2004" (2004). U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers. 62. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark/62 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Park Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. NATIONAL PARK SERVICE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HERITAGE MATTERS NEWS OF THE NATION’S DIVERSE CULTURAL HERITAGE National Museum of the American Indian Opens to Great Fanfare INSIDE THIS ISSUE The Smithsonian Institution, entrance to catch the rising sun, in honor of Private First Class Curriculum materials National Museum of the American a prism window, and a 120-foot- Lori A. Piestewa, who was the first available, p. 3 Indian (NMAI), opened its doors high atrium called the Potomac. Native American servicewoman to Conferences to the public on September 21, NMAI was designed by Jones & give her life in overseas combat. -

GAR Posts in PA

Grand Army of the Republic Posts - Historical Summary National GAR Records Program - Historical Summary of Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Posts by State PENNSYLVANIA Prepared by the National Organization SONS OF UNION VETERANS OF THE CIVIL WAR INCORPORATED BY ACT OF CONGRESS No. Alt. Post Name Location County Dept. Post Namesake Meeting Place(s) Organized Last Mentioned Notes Source(s) No. PLEASE NOTE: The GAR Post History section is a work in progress (begun 2013). More data will be added at a future date. 000 (Department) N/A N/A PA Org. 16 January Dis. 1947 Provisional Department organized 22 November 1866. Permanent Beath, 1889; Carnahan, 1893; 1867 Department 16 January 1867 with 19 Posts. The Department National Encampment closed in 1947, and its remaining members were transferred to "at Proceedings, 1948 large" status. 001 GEN George G. Meade Philadelphia Philadelphia PA MG George Gordon Meade (1815- Wetherill House, Sansom Street Chart'd 16 Oct. Originally chartered by National HQ. It was first commanded by Beath, 1889; History of the 1872), famous Civil War leader. above Sixth (1866); Home Labor 1866; Must'd 17 COL McMichael. Its seniority was challenged by other Posts George G. Meade Post No. League Rooms, 114 South Third Oct. 1866 named No. 1 in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. It was found to be One, 1889; Philadelphia in the Street (1866-67); NE cor. Broad the ranking Post in the Department and retained its name as Post Civil War, 1913 and Arch Streets (1867); NE cor. No. 1. It adopted George G. Meade as its namesake on 8 Jan. -

German- American Studies NEWSLETTER SGAS.ORG

SOCIETY FOR VOLUME 37 NO. 1 German- American Studies NEWSLETTER SGAS.ORG PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE An Excursion to the Cradle of German Texas North. It turns out there was wine involved. According to the Cat Spring chronicle, one Lorenz Mueller suggested the An invitation from the New Ulm Chamber of Commerce name to New Ulm in honor of his origins, stressing his point provided the occasion for a pleasant drive last weekend “by treating those present at the discussion to a case of to the area where Germans first gained a foothold in Texas, Rhine wine.” In some ways Cat Spring, a dozen miles east even before the Lone Star Republic was established. Heading of New Ulm, rivals Industry as the cradle of German Texas. Its west out of my college town, you soon cross the Brazos River Landwirtschaftlicher Verein, the oldest agricultural society in and then turn south, traversing the bottomlands and cotton Texas, kept its minutes in German all the way down to 1942, fields that still bear traces of plantation society. Then on past and is still thriving as it approaches its 160th anniversary. the Baptist Church that Sam Houston attended and a side Nearby Millheim once claimed six holders of German road to the creek where he was baptized. From there on, doctorates; at the Verein, these Latin farmers discussed you’re in a different cultural landscape. Even with names with peasant farmers the most effective techniques of Texas like William Penn, or Sandy Hill, and Prairie Hill, the Lutheran agriculture, and also engaged in a bit of conviviality. -

Pittsburgh Concert Programs at Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

Use Command F (⌘F) or CTRL + F to search this document ORGANIZATION DATE YEAR PROGRAM VENUE LOCATION John H. Mellor 11/27/1855 1855 Soiree by the pupils of Mrs. Ernest Piano warerooMs Music of John H. Mellor DepartMent: Pittsburgh Music Archive, #41 Protestant Episcopal Church of 12/29/1856 1856 Concert of Sacred Music Lafayette Hall Music East Liberty DepartMent: Pittsburgh Music Archive, #46 St. Andrew’s Church 1858 1858 Festival Concert by choral society at St. St. Andrew’s Music Andrew’s Church Church DepartMent: Pittsburgh Music Archive, #46 Lafayette Hall 2/9/1858 1858 Soiree Musicale in Lafayette Hall Lafayette Hall Music DepartMent: Pittsburgh Music Archive, #46 2/21/1859 1859 Mlle. PiccoloMini Music DepartMent: Pittsburgh Music Archive, #46 Grand Concert 186- 1860 The Grand Vocal & InstruMental concert of unknown Music the world-faMed Vienna Lady Orchestra DepartMent: Pittsburgh Concert PrograMs, v. 4 Presbyterian Church, East 5/20/186- 1860 Concert in the Presbyterian Church, East Presbyterian Churc Music Liberty Liberty, Charles C. Mellor, conductor h, East Liberty DepartMent: Pittsburgh Music Archive, #41 St. Peter’s Church 6/18/1860 1860 Oratorios - benefit perforMance for St. Peter’s Church Music purchase of organ for St. Mark’s Church in on Grant Street DepartMent: East BirMinghaM Pittsburgh Music Archive, #46 Returned Soldier Boys 1863 1863 Three PrograMs ChathaM and Wylie Music Ministrels Ave. DepartMent: Pittsburgh Concert PrograMs, v. 1 Green FaMily Minstrels 12/11/1865 1865 Benefit PrograM AcadeMy of Music Music DepartMent: Pittsburgh Concert PrograMs, v. 1 St. John's Choir 12/30/1865 1865 Benefit PrograM BirMinghaM Town Music Hall, South Side DepartMent: Pittsburgh Concert PrograMs, v. -

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania ?

THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA President, Boyd Lee Spahr Vice-Presidents Boies Penrose William C. Tuttle Ernest C. Savage Roy F. Nichols Charles Stewart Wurts Isaac H. Clothier, Jr. Secretary, Richmond P. Miller Treasurer, Frederic R. Kirkland Councilors Thomas C. Cochran Henry S. Jeanes, Jr. Harold D. Saylor William Logan Fox A. Atwater Kent, Jr. Grant M. Simon J. Welles Henderson Sydney E. Martin Frederick B. Tolles Penrose R. Hoopes Henry R. Pemberton H. Justice Williams Counsel, R. Sturgis Ingersoll ? Director, R. N. Williams, 2nd DEPARTMENT HEADS: Nicholas B. Wainwright, Research; Lois V. Given, Publications; J. Harcourt Givens, Manuscripts; Raymond L. Sutcliffe, Library; Sara B. Pomerantz, Assistant to the Treasurer; Howard T. Mitchell, Photo-reproduction; David T. McKee, Building Superintendent. * ¥ ¥ <*> Founded in 1824, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania has long been a center of research in Pennsylvania and American history. It has accumulated an important historical collection, chiefly through contributions of family, political, and business manuscripts, as well as letters, diaries, newspapers, magazines, maps, prints, paintings, photographs, and rare books. Additional contributions of such a nature are urgently solicited for preservation in the Society's fireproof building where they may be consulted by scholars. Membership. There are various classes of membership: general, $10.00; associate, $25.00; patron, $100.00; life, $250.00; benefactor, $1,000. Members receive certain privileges in the use of books, are invited to the Society's historical addresses and receptions, and receive The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Those interested in joining the Society are invited to submit their names. Hours. The Society is open to the public Monday, 1 P.M. -

German Day Week Come Celebrate the Tri-State’S 123Rd Deutscher Tag

Ge rman- Ame rican N ews Deutsch-Amerikanische Nachrichten Volume 24 April, May, June 2018 Issue 2 German Day Week Come Celebrate the Tri-State’s 123rd Deutscher Tag German Day Week Kickoff Keg Tapping Date: Wednesday, May 30, 2018 Time 7:00 p.m. Place: Hofbräuhaus Newport German-American German Day Kickoff Citizens League of Greater Cincinnati Date: Saturday, June 2, 2018 Time: 10:30 a.m. Place: Findlay Market German Day Celebration Date: Sunday, June 3, 2018 Time: 11:00 a.m. - 11:00 p.m. Place: Hofbräuhaus Newport This marks the 123rd celebration of German Day sponsored by the German-American Citizens League (GACL). In honor of this historic occasion German Day Week has been proclaimed in the Tri-State (Hamilton County and the Cities of Cincinnati, Covington and Newport) for the week of May 28 - June 3, 2018. German Day Week Kickoff Keg Tapping at HBH Newport - Wednesday, May 30, 2018 at 7 PM. On Saturday, June 2, 2018 at 10:30 AM the parade and opening ceremonies will take place at the historic Findlay Market, featuring representatives of area German-American societies, as well as the German heritage of the Market. This will include performances by German dance and music groups as well. On Sunday, June 3, beginning at 11:00 AM until 11:00 PM enjoy the fi ne food and beverage and German music at the Hofbräuhaus Newport. This year’s German Day Grand Prize consists of a dinner party for 30 at the Hofbräuhaus (excluding beverages), The GACL will offer hourly raffl e prizes throughout the day, and a grand raffl e at 5:30 P.M. -

The History of Pope Farms Owners, Settlers, and Farmers

The History of Pope Farms Owners, Settlers, and Farmers By: The Friends of Pope Farm Conservancy Contents Page Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……….iii Preface…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……iv-v Figures Figure 1 - State of Wisconsin, Dane County highlighted………………………………………….……vi Figure 2 - Dane County Map, Town of Middleton highlighted……………………………….….….vi Figure 3 - Plat Map 1861, Section 17…………………………………………………..…………………......vii Figure 4 - Town of Middleton, Section 17…………………………………………………………………..viii Figure 5 - Three Farms, Satellite image with three farms………………………………..….………..ix Figure 6 - Glacial Debris, LiDAR image of glacial debris on three farms….………………………x Figure 7 - Town of Middleton, Section 20……………………………………………………………………..xi CHAPTER 1 - Pre-Settlement of Pope Farm Conservancy Pre-Settlement timeline of Pope Farm Conservancy ………………………………………….……..…………..1-2 Genevieve Grignon family, Third Treaty of Prairie Du Chien…..……………………………..……………….2-4 Emanuel Boizard ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….4-5 CHAPTER 2 – Eastern Portion of Pope Farm Conservancy Historical Timeline of the Eastern Portion of Pope Farm Conservancy ……………….……….………..7-9 Chronology George and Christina Seibert …………………………………………………………………….…………..10-13 Carl Schenk and Charles T. Schwenn families……………………………………………….…………14-22 Lappley, Grob, and Mahoney families ……………………………………………………………………22-28 Pope family, Eastern Farm …………………………………………………………………………………….29-30 Pope Farm Elementary School ………………………………………………………………………………33-34 Remembrances