Guide to GIS for Public Gardens: Botanical Gardens, Zoos, and Parks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Paper on Spatial Data Infrastructure Standards

Integrated Spatial Planning Toolkit Module X: Technical Paper on Spatial Data Infrastructure Standards Draft October 28 2009 - for circulation and comment Prepared by: Dr Melissa Burgess Integrated Spatial Planning and Communications Specialist United Nations Development Programme Regional Center Bangkok Email: [email protected] Background: The United Nations Development Program - Regional Centre in Bangkok (UNDP-RCB) is managing a project funded by the Government of Japan titled “Better Informed Environmental Decision Making through Integrated Spatial Planning”, which is under implementation in the Asia-Pacific Region. A Toolkit designed to assist governments develop their capacity for Integrated Spatial Planning is being developed as part of this project. This document comprises the first draft of Module X of this Integrated Spatial Planning Toolkit, on Spatial Data Infrastructure Standards. Integrated Spatial Planning Toolkit Module X: Spatial Data Infrastructure Standards Page 1 Technical Paper on Spatial Data Introduction Spatial Data Infrastructure standards Spatial Data Infrastructure (SDI) comprise of those policies, organisational remits, data, technologies, standards, delivery mechanisms, and financial and human resources necessary to ensure that users of spatial data are supported in meeting their objectives by improving capacity for geographic information exchanges, harmonization and integration. SDI Standards describe objects, features and items that are collected, automated or affected by the activities or the functions of organisations. The development, publication and acceptance of data standards are important goals of an integrated information management solution. Such standards are essential for all users and producers of data and information. They are particularly important in any co-management, co-maintenance or partnership arrangements where data and information need to be shared or aggregated. -

Overview of GIS Applications Risk Assessment and Risk Management of Climate Change Hazards

Overview of GIS applications risk assessment and risk management of climate change hazards Fact irrigated lands Planed irrigated lands Watershed Water bodies Settlements River Soil types Overview of GIS applications risk assessment and risk management of climate change hazards © 2010 PREPARED The European Commission is funding the Collaborative project ‘PREPARED Enabling Change’ (PREPARED, project number 244232) within the context of the Seventh Framework Programme 'Environment'.All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a database or retrieval system, or published, in any form or in any way, electronically, mechanically, by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means without prior written permission from the publisher COLOPHON Title Overview of GIS applications, risk assessment and risk management of climate change hazards Report number Prepared 2011.015 Deliverable number D2.5.1 Author(s) Ielizaveta Dunaieva (Crimean Scientific and Research Center) Victor Popovych (Crimean Scientific and Research Center) Elisa Traverso (Iren Acqua Gas) Quality Assurance Patrick Smeets (KWR Watercycle Research Institute) Document history Version Team member Status Date update Comments 01 Ielizaveta Dunaieva Draft 27-08-2010 Chapters 1-4, 6 02 Ielizaveta Dunaieva Draft 24-06-2011 Applications from cities Simferopol and Genoa added 03 Patrick Smeets Final 03-08-2011 QA by WA leader This report is: PU = Public Summary The first step to prepare for climate change effects on the water cycle is a risk assessment for the observed system to be prepared and, if it is necessary, protected. Risk assessment (RA) means the determination of qualitative and quantitative value of risks, related to a certain situation and the recognized hazards. -

Spatial Data Management for Disaster Risk Management

Collecting, creating and analysing spatial data for Disaster Risk Assessments: the issues and pitfalls Maryna Strydom (GIS Tg SA) Tel: (011) 441 6163 [email protected] Overview Spatial data types, representation and formats X and Y axes, and offsets Projections Data management principles Metadata Data analyses Storage/Curation of data “… data is every scientist’s second priority. When scientists are evaluated … their efforts in curating, managing and quality assurance of data sets that future generations of researchers can use are not taken into account … .” Dr J-B Minster, Chair: ICSU World Data Center System. Collecting and analysing spatial data during Disaster Risk Assessments is generally seen as a relatively easy one where data is collected and thereafter most of the actual project work revolves around the analysis of the data and modeling the risks… However, the time and effort that it takes to get the spatial data into a usable format and eventually give it back to the end-users in a way that they would be able to utilize it effectively in future exercises/projects, is generally underestimated… Spatial Data types Notable commercial or proprietary GIS software CAD / GIS (vector/raster): Autodesk – MapGuide and AutoCAD . Intergraph – photogrammetry . ERDAS IMAGINE – Remote Sensing , and Photogrammetry by Leica Geosystems Geospatial Imaging. ESRI – ArcView 3.x , ArcGIS , ArcSDE , ArcIMS , ArcServer, ArcPad (for GPS). IDRISI – imagery/remote sensing by Clark Labs. MapInfo – MapInfo Professional . MapPoint – by Microsoft. Caliper –Maptitude , TransCAD and TransModeler . GIS for transportation. Pictometry – allows oblique images to be draped with shapefiles. Black Coral Inc —geospatial collaboration capabilities that enable better outcomes for personnel and tactical teams operating in emergency response and military environments. -

What Is Openjump

http://tsusiatsoftware.net/jts/javadoc/index.html What is OpenJUMP Download OpenJUMP facts sheet "JUMP is a computer program that uses a unified mapping platform as a visualisation framework..." (changed ESRI keynote on What is GIS? by M. Bobzien) But to be a bit more serious - OpenJUMP is an open source GIS software written in Java and it is based on JUMP GIS by Vivid Solutions. Furthermore... It is a Vector GIS that can read rasters as well . OpenJUMP is known to work on Windows, Linux and Mac platforms, but should work on any operating system that runs Java 1.5 or later. It is not just another free demo viewer, but you can edit, save, analyze etc. with JUMP / OpenJUMP . It works, even with medium size datasets, and with professional touch . It provides a GIS API with a flexible plugin structure, so that new features are relatively easy to develope around the sound mapping platform. It utilizes OGC standards like SFS, GML, WMS and WFS . It is already translated in English, Finnish, French, German, Italian, Portugese and Spanish. The translation in other languages is in progress. ..and it is free (under the GPL license). OpenJUMP finally adds some key enhancements to the original JUMP software, including: . I18N (internationalization), . more drawing and geometry editing tools, . advanced attribute query, . enhanced set of selection tools, . image export in Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) format, . function to copy objects including attributes, . it can show layers dependent on the current map scale, . more classification methods for thematic coloring . ... OpenJUMP is the result of a larger umbrella project called the JUMP Pilot Project (JPP). -

Evolution Et Ressources Des Logiciels SIG Libres

Evolution et ressources des logiciels SIG libres Veille Technologique 2009 Fabrice Dubertret Raphaël Loué Chloé Romier 2 Introduction Qu’est-ce qu’un logiciel SIG Open-Source? • Un système d'information géographique (SIG) est un système d'information capable d'organiser et de présenter des données alphanumériques spatialement référencées, ainsi que de produire des plans et des cartes • La désignation Open Source, "source ouverte" en français ou code source libre, s'applique aux logiciels dont la licence respecte des critères précisément établis par l'Open Source Initiative, c'est-à-dire la possibilité de libre redistribution, d'accès au code source, et de travaux dérivés • Intérêt économique, fonctionnel et évolutif 3 Sommaire I Fonctionnement général des logiciels SIG Open-Source 1 Projets et standards – OGC 2 Développement, financement 3 Compatibilité et longévité II Présentation de quelques logiciels 1 OpenJUMP 2 gvSIG 3 uDig 4 GRASS et QGIS III Ressources 1 Forums 2 Didacticiels / Tutoriels Conclusion 4 1 _ Projets et standards - OGC 2 _ Développement, financement 3 _ Compatibilité et longévité 5 Généralités L’Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) • Consortium international fondé en 1994 pour développer et promouvoir des standards ouverts (spécifications OpenGIS®) garantir l'interopérabilité des contenus, des services et des échanges favoriser la coopération entre développeurs, fournisseurs et utilisateurs basé sur le principe du consensus volontaire • Recommandations faites et normes: WMS (Web Map Service), WFS (Web Feature Service), SFS (Simple Features – SQL), etc. 6 Généralités Développement et financement • L’aide initiale Développement d’un code fonctionnel Aide souvent gouvernementale GRASS (US Army Corps of Engineers) MapServer (NASA & Minnesota DNR), etc. -

STANDARD SOFTWARE for GIS (Unit: II) Semester: II Paper Code: GIS 09 Name of Paper: Advanced Remote Sensing & GIS PG Diploma in RS & GIS Dr

STANDARD SOFTWARE FOR GIS (Unit: II) Semester: II Paper Code: GIS 09 Name of Paper: Advanced Remote Sensing & GIS PG Diploma in RS & GIS Dr. SHYAMA PRASAD MUKHERJEE UNIVERSITY, RANCHI STANDARD SOFTWARE FOR GIS Software that is used to create, manage, analyze and visualize geographic data is usually incorporated under the umbrella term ‘GIS software’ (Steiniger & Weibel, 2009). Typical applications for GIS software include the evaluation of places for the location of new stores, the management of power and gas lines, the creation of maps, the analysis of past crimes for crime prevention, route calculations for transport tasks, the management of forests, parks and infrastructure, such as roads and water ways, as well as applications in risk analysis of natural hazards, and emergency planning and response. For this multitude of applications different types of GIS functions are required and different categories of GIS software exist, which provide a particular set of functions needed to fulfil certain data management tasks. Different functional categories of GIS software can be identified with respect to the tool sets that GIS software offers, and with respect to the tasks that can be accomplished. Such tasks involve basic activities that are common to daily computer usage such as (1) data visualization and exploration, (2) data creation, (3) data editing and (4) data storage. Other common GIS tasks include (5) data conflation, i.e., integration of data from different sources (Blasby, Davis, & Kim, 2002), (6) data queries to select a subset of the data, (7) data analysis, which we consider to be the creation of new information (output) from existing data (input), (8) data transformation, as some analysis tasks require the user to transform, or manipulate, the data beforehand (e.g. -

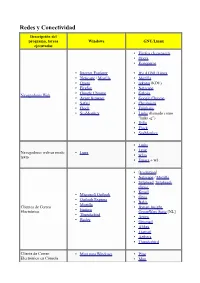

Redes Y Conectividad Descripción Del Programa, Tareas Windows GNU/Linux Ejecutadas • Firefox (Iceweasel) • Opera • Konqueror

Redes y Conectividad Descripción del programa, tareas Windows GNU/Linux ejecutadas • Firefox (Iceweasel) • Opera • Konqueror • Internet Explorer • IEs 4 GNU/Linux • Netscape / Mozilla • Mozilla • Opera • rekonq (KDE) • Firefox • Netscape • Google Chrome • Galeón Navegadores Web • Avant Browser • Google Chrome • Safari • Chromium • Flock • Epiphany • SeaMonkey • Links (llamado como "links -g") • Dillo • Flock • SeaMonkey • Links • • Lynx Navegadores web en modo Lynx • texto w3m • Emacs + w3. • [Evolution] • Netscape / Mozilla • Sylpheed , Sylpheed- claws. • Kmail • Microsoft Outlook • Gnus • Outlook Express • Balsa • Mozilla Clientes de Correo • Bynari Insight • Eudora Electrónico GroupWare Suite [NL] • Thunderbird • Arrow • Becky • Gnumail • Althea • Liamail • Aethera • Thunderbird Cliente de Correo • Mutt para Windows • Pine Electrónico en Cónsola • Mutt • Gnus • de , Pine para Windows • Elm. • Xemacs • Liferea • Knode. • Pan • Xnews , Outlook, • NewsReader Lector de noticias Netscape / Mozilla • Netscape / Mozilla. • Sylpheed / Sylpheed- claws • MultiGet • Orbit Downloader • Downloader para X. • MetaProducts Download • Caitoo (former Kget). Express • Prozilla . • Flashget • wxDownloadFast . • Go!zilla • Kget (KDE). Gestor de Descargas • Reget • Wget (console, standard). • Getright GUI: Kmago, QTget, • Wget para Windows Xget, ... • Download Accelerator Plus • Aria. • Axel. • Httrack. • WWW Offline Explorer. • Wget (consola, estándar). GUI: Kmago, QTget, Extractor de Sitios Web Teleport Pro, Webripper. Xget, ... • Downloader para X. • -

Newsletter Ecdl-Gis@Lartu Ecdl-Gis

NEWSLETTER ECDL-GIS@LARTU ECDL-GIS NEWSLETTER Anno I - Numero 2 – Novembre 2011 - Politecnico e Università di Torino - Dipartimento Interateneo Territorio [ DITER ] - Laboratorio di Analisi e Rappresentazioni Territoriali ed Urbane [ LARTU ] - Castello del Valentino Manica Chevalley - Primo e secondo piano interrato - Viale Mattioli, 39 - 10125 Torino - Tel. +390115647478 - Fax. +390115647451 – www.ecdlgis.polito.it - www.lartu.polito.it – [email protected] – Test Center ECDL-GIS NEWSLETTER ECDL-GIS@LARTU Useful resources [!Update Your Bookmarks!] - Unsorted, unclassified GIS tools, blogs and other resources… ..................................................................................................................................5 GeoNetwork .............................................................................................................................................5 Nasa World Wind ....................................................................................................................................5 NatureServe Vista: Decision Support for Better Planning ................................................................5 Digital Media Center ...............................................................................................................................6 Biodiversity Informatics ..........................................................................................................................7 Open Topography ...................................................................................................................................7 -

Exploring Opportunities with Open Source GIS

Published by : International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) http://www.ijert.org ISSN: 2278-0181 Vol. 9 Issue 05, May-2020 Exploring Opportunities with Open Source GIS Sandhya M C Asst. Prof. Department of Civil Engineering Ahmedabad Institute of Technology Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. Abstract—There are many Commercial software developers and other independent users who wanted to available for various GIS Applications. These Software are extend the core functionality of this software. These very costly and making unaffordable for the General users. plugins are available for all users, according to our needs So we need an alternate option which is Economical, Feature we can install the appropriate plugins. There are more than rich & similar Capabilities as that of Commercial ones. Such 650 plugins available right now. possibilities can be explored by Evaluating Open Source GIS software. Recently open source software start playing vital role in Industry, Academics and Research. Quantum GIS The Distribution and sharing of Geo-spatial data to a wider (QGIS) is most popular, leading and user friendly open community play an important role in development. These source GIS software. It is very easy to use, extensible, and data can be accessed by any sources Desktops, Laptops or has a constantly growing community and user base. More mobiles through internet. Sharing and Dissemination of and more Private users and organizations choose QGIS as data offers possibilities to access right data at right time to their mainstream GIS software. Hence it is necessary to make right kind of decisions. It provides communication study the opportunities of this open source software as an between different stakeholders such as Government alternative to the established proprietary software. -

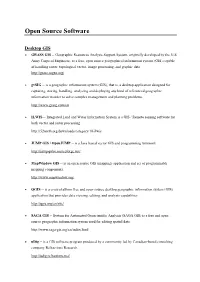

Open Source Software

Open Source Software Desktop GIS GRASS GIS -- Geographic Resources Analysis Support System, originally developed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers:, is a free, open source geographical information system (GIS) capable of handling raster, topological vector, image processing, and graphic data. http://grass.osgeo.org/ gvSIG -- is a geographic information system (GIS), that is, a desktop application designed for capturing, storing, handling, analyzing and deploying any kind of referenced geographic information in order to solve complex management and planning problems. http://www.gvsig.com/en ILWIS -- Integrated Land and Water Information System is a GIS / Remote sensing software for both vector and raster processing. http://52north.org/downloads/category/10-ilwis JUMP GIS / OpenJUMP -- is a Java based vector GIS and programming formwork. http://jump-pilot.sourceforge.net/ MapWindow GIS -- is an open source GIS (mapping) application and set of programmable mapping components. http://www.mapwindow.org/ QGIS -- is a cross-platform free and open-source desktop geographic information system (GIS) application that provides data viewing, editing, and analysis capabilities http://qgis.org/en/site/ SAGA GIS -- System for Automated Geoscientific Analysis (SAGA GIS) is a free and open source geographic information system used for editing spatial data. http://www.saga-gis.org/en/index.html uDig -- is a GIS software program produced by a community led by Canadian-based consulting company Refractions Research. http://udig.refractions.net/ Capaware -- is a 3D general purpose virtual world viewer. http://www.capaware.org/ FalconView -- is a mapping system created by the Georgia Tech Research Institute. https://www.falconview.org/trac/FalconView Web map servers GeoServer -- an open-source server written in Java - allows users to share process and edit geospatial data. -

Open Source GIS Software Applications Include GRASS, a Project Started in 1982 by the US Army but Is Now Open Source, and QGIS (Otherwise Known As Quantum GIS)

Open Source GIS and Freeware GIS Applications An open source application by definition is software that you can freely access and modify the source code for. Open source projects typically are worked on by a community of volunteer programmers. Open source GIS programs are based on different base programming languages. Three main groups of open source GIS (outside of web GIS) in terms of programming languages are: “C” languages, Java, and .NET. The first group would be the group that uses “C” language for its implementation. This is the more mature of the groups of open source GIS, probably for the simple reason that is the group that has been working on GIS software applications the longest and has a long history of reuse of code. The libraries in the “C” group, from the base infrastructure, and include some capabilities like coordinate projection that make them very useful and popular. Popular “C” based open source GIS software applications include GRASS, a project started in 1982 by the US Army but is now open source, and QGIS (otherwise known as Quantum GIS). The second group of Open Source GIS would be the ones that use JAVA as the implementation language. JTS, central library for the Java GIS development, offers some geospatial functions that allow to compare objects and return a boolean true/false result indicating the existence (or absence) of any questioned spatial relationship. Other operators, like Union or Buffer, which are very hard to code, are offered in this group making it very appreciated by GIS developers. GeoTools, Geoserve, and OpenMap, are among the most popular open source GIS in this group of JAVA tools. -

1 Geographical Information Systems (GIS)

Geographical Information Systems (GIS) Introduction Geographical Information System (GIS) is a technology that provides the means to collect and use geographic data to assist in the development of Agriculture. A digital map is generally of much greater value than the same map printed on a paper as the digital version can be combined with other sources of data for analyzing information with a graphical presentation. The GIS software makes it possible to synthesize large amounts of different data, combining different layers of information to manage and retrieve the data in a more useful manner. GIS provides a powerful means for agricultural scientists to better service to the farmers and farming community in answering their query and helping in a better decision making to implement planning activities for the development of agriculture. Overview of GIS A Geographical Information System (GIS) is a system for capturing, storing, analyzing and managing data and associated attributes, which are spatially referenced to the Earth. The geographical information system is also called as a geographic information system or geospatial information system. It is an information system capable of integrating, storing, editing, analyzing, sharing, and displaying geographically referenced information. In a more generic sense, GIS is a software tool that allows users to create interactive queries, analyze the spatial information, edit data, maps, and present the results of all these operations. GIS technology is becoming essential tool to combine various maps and remote sensing information to generate various models, which are used in real time environment. Geographical information system is the science utilizing the geographic concepts, applications and systems.