Themartinlutherking,Jr.Papersproject

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BERKELEY SUMMER SESSIONS the Political Philosophy of Martin Luther King, Jr

Syllabus https://elearning.berkeley.edu/AngelUploads/Content/2013SUC... Printer Friendly Version BERKELEY SUMMER SESSIONS The Political Philosophy of Martin Luther King, Jr. (African American Studies 124, Summer Session 2013) about the course | materials | learning activities | grading | course policies | course outline About the Course Back to Top Course Description The life of Martin Luther King, Jr., provides a rare opportunity to understand the crucial issues of an era that shaped a good deal of contemporary America. As that era’s greatest leader, King’s life helps us both focus history and humanize it. As a profound thinker, as well as an activist, King epitomizes the interdependence of academic excellence and social responsibility. By examining the forces that shaped King’s life and his impact on society, we should gain some sense of history and historical possibility. By critically reviewing his political philosophy we should gain some appreciation of its depth and relevance for today. Recently, for example, protesters in Egypt were singing "We Shall Overcome." Each student will be expected to fully participate in the course including daily reading, watching the multimedia lecture presentations, engaging in interaction with the graduate student instructors and professor, posting short essays to a discussion board, interacting with peers in study sections, writing a critical book review of the Tyson book, taking four quizzes, and completing the mid-term and final examinations. Each quiz will count ten points. The mid-term and final examinations will count 20 points each and the critical book review will count 20 points. Extensions and incompletes will only be granted in rare circumstances. -

Negroes Are Different in Dixie: the Press, Perception, and Negro League Baseball in the Jim Crow South, 1932 by Thomas Aiello Research Essay ______

NEGROES ARE DIFFERENT IN DIXIE: THE PRESS, PERCEPTION, AND NEGRO LEAGUE BASEBALL IN THE JIM CROW SOUTH, 1932 BY THOMAS AIELLO RESEARCH ESSAY ______________________________________________ “Only in a Negro newspaper can a complete coverage of ALL news effecting or involving Negroes be found,” argued a Southern Newspaper Syndicate advertisement. “The good that Negroes do is published in addition to the bad, for only by printing everything fit to read can a correct impression of the Negroes in any community be found.”1 Another argued that, “When it comes to Negro newspapers you can’t measure Birmingham or Atlanta or Memphis Negroes by a New York or Chicago Negro yardstick.” In a brief section titled “Negroes Are Different in Dixie,” the Syndicate’s evaluation of the Southern and Northern black newspaper readers was telling: Northern Negroes may ordain it indecent to read a Negro newspaper more than once a week—but the Southern Negro is more consolidated. Necessity has occasioned this condition. Most Southern white newspapers exclude Negro items except where they are infamous or of a marked ridiculous trend… While his northern brother is busily engaged in ‘getting white’ and ruining racial consciousness, the Southerner has become more closely knit.2 The advertisement was designed to announce and justify the Atlanta World’s reformulation as the Atlanta Daily World, making it the first African-American daily. This fact alone probably explains the advertisement’s “indecent” comment, but its “necessity” argument seems far more legitimate.3 For example, the 1932 Monroe Morning World, a white daily from Monroe, Louisiana, provided coverage of the black community related almost entirely to crime and church meetings. -

Race, Riots, and Public Space in Harlem, 1900-1935

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-9-2017 The Breath Seekers: Race, Riots, and Public Space in Harlem, 1900-1935 Allyson Compton CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/166 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Breath Seekers: Race, Riots, and Public Space in Harlem, 1900-1935 by Allyson Compton Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2017 Thesis Sponsor: April 10, 2017 Kellie Carter Jackson Date Signature April 10, 2017 Jonathan Rosenberg Date Signature of Second Reader Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Public Space and the Genesis of Black Harlem ................................................. 7 Defining Public Space ................................................................................................... 7 Defining Race Riot ....................................................................................................... 9 Why Harlem? ............................................................................................................. 10 Chapter 2: Setting -

STANDING COMMITTEES of the HOUSE Agriculture

STANDING COMMITTEES OF THE HOUSE [Democrats in roman; Republicans in italic; Resident Commissioner and Delegates in boldface] [Room numbers beginning with H are in the Capitol, with CHOB in the Cannon House Office Building, with LHOB in the Longworth House Office Building, with RHOB in the Rayburn House Office Building, with H1 in O’Neill House Office Building, and with H2 in the Ford House Office Building] Agriculture 1301 Longworth House Office Building, phone 225–2171, fax 225–8510 http://agriculture.house.gov meets first Wednesday of each month Collin C. Peterson, of Minnesota, Chair Tim Holden, of Pennsylvania. Bob Goodlatte, of Virginia. Mike McIntyre, of North Carolina. Terry Everett, of Alabama. Bob Etheridge, of North Carolina. Frank D. Lucas, of Oklahoma. Leonard L. Boswell, of Iowa. Jerry Moran, of Kansas. Joe Baca, of California. Robin Hayes, of North Carolina. Dennis A. Cardoza, of California. Timothy V. Johnson, of Illinois. David Scott, of Georgia. Sam Graves, of Missouri. Jim Marshall, of Georgia. Jo Bonner, of Alabama. Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, of South Dakota. Mike Rogers, of Alabama. Henry Cuellar, of Texas. Steve King, of Iowa. Jim Costa, of California. Marilyn N. Musgrave, of Colorado. John T. Salazar, of Colorado. Randy Neugebauer, of Texas. Brad Ellsworth, of Indiana. Charles W. Boustany, Jr., of Louisiana. Nancy E. Boyda, of Kansas. John R. ‘‘Randy’’ Kuhl, Jr., of New York. Zachary T. Space, of Ohio. Virginia Foxx, of North Carolina. Timothy J. Walz, of Minnesota. K. Michael Conaway, of Texas. Kirsten E. Gillibrand, of New York. Jeff Fortenberry, of Nebraska. Steve Kagen, of Wisconsin. Jean Schmidt, of Ohio. -

Black Women As Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools During the 1950S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Hostos Community College 2019 Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools during the 1950s Kristopher B. Burrell CUNY Hostos Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ho_pubs/93 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] £,\.PYoo~ ~ L ~oto' l'l CILOM ~t~ ~~:t '!Nll\O lit.ti t~ THESTRANGE CAREERS OfTHE JIMCROW NORTH Segregation and Struggle outside of the South EDITEDBY Brian Purnell ANOJeanne Theoharis, WITHKomozi Woodard CONTENTS '• ~I') Introduction. Histories of Racism and Resistance, Seen and Unseen: How and Why to Think about the Jim Crow North 1 Brian Purnelland Jeanne Theoharis 1. A Murder in Central Park: Racial Violence and the Crime NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS Wave in New York during the 1930s and 1940s ~ 43 New York www.nyupress.org Shannon King © 2019 by New York University 2. In the "Fabled Land of Make-Believe": Charlotta Bass and All rights reserved Jim Crow Los Angeles 67 References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or John S. Portlock changed since the manuscript was prepared. 3. Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in Names: Purnell, Brian, 1978- editor. -

The Honorable Harold H. Greene

THE HONORABLE HAROLD H. GREENE U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia Oral History Project The Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit Oral History Project United States Courts The Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit District of Columbia Circuit The Honorable Harold H. Greene U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia Interviews conducted by: David Epstein, Esquire April 29, June 25, and June 30, 1992 NOTE The following pages record interviews conducted on the dates indicated. The interviews were electronically recorded, and the transcription was subsequently reviewed and edited by the interviewee. The contents hereof and all literary rights pertaining hereto are governed by, and are subject to, the Oral History Agreements included herewith. © 1996 Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit. All rights reserved. PREFACE The goal of the Oral History Project of the Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit is to preserve the recollections of the judges who sat on the U.S. Courts of the District of Columbia Circuit, and judges’ spouses, lawyers and court staff who played important roles in the history of the Circuit. The Project began in 1991. Most interviews were conducted by volunteers who are members of the Bar of the District of Columbia. Copies of the transcripts of these interviews, a copy of the transcript on 3.5" diskette (in WordPerfect format), and additional documents as available – some of which may have been prepared in conjunction with the oral history – are housed in the Judges’ Library in the United States Courthouse, 333 Constitution Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. -

Implementation of the Helsinki Accords Hearings

BASKET III: IMPLEMENTATION OF THE HELSINKI ACCORDS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE NINETY-SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION THE CRISIS IN POLAND AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE HELSINKI PROCESS DECEMBER 28, 1981 Printed for the use of the - Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 9-952 0 'WASHINGTON: 1982 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE DANTE B. FASCELL, Florida, Chairman ROBERT DOLE, Kansas, Cochairman ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah SIDNEY R. YATES, Illinois JOHN HEINZ, Pennsylvania JONATHAN B. BINGHAM, New York ALFONSE M. D'AMATO, New York TIMOTHY E. WIRTH, Colorado CLAIBORNE PELL, Rhode Island MILLICENT FENWICK, New Jersey PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont DON RITTER, Pennsylvania EXECUTIVE BRANCH The Honorable STEPHEN E. PALMER, Jr., Department of State The Honorable RICHARD NORMAN PERLE, Department of Defense The Honorable WILLIAM H. MORRIS, Jr., Department of Commerce R. SPENCER OLIVER, Staff Director LYNNE DAVIDSON, Staff Assistant BARBARA BLACKBURN, Administrative Assistant DEBORAH BURNS, Coordinator (II) ] CONTENTS IMPLEMENTATION. OF THE HELSINKI ACCORDS The Crisis In Poland And Its Effects On The Helsinki Process, December 28, 1981 WITNESSES Page Rurarz, Ambassador Zdzislaw, former Polish Ambassador to Japan .................... 10 Kampelman, Ambassador Max M., Chairman, U.S. Delegation to the CSCE Review Meeting in Madrid ............................................................ 31 Baranczak, Stanislaw, founder of KOR, the Committee for the Defense of Workers.......................................................................................................................... 47 Scanlan, John D., Deputy Assistant Secretary for European Affairs, Depart- ment of State ............................................................ 53 Kahn, Tom, assistant to the president of the AFL-CIO .......................................... -

Unwise and Untimely? (Publication of "Letter from a Birmingham Jail"), 1963

,, te!\1 ~~\\ ~ '"'l r'' ') • A Letter from Eight Alabama Clergymen ~ to Martin Luther J(ing Jr. and his reply to them on order and common sense, the law and ~.. · .. ,..., .. nonviolence • The following is the public statement directed to Martin My dear Fellow Clergymen, Luther King, Jr., by eight Alabama clergymen. While confined h ere in the Birmingham City Jail, I "We the ~ders igned clergymen are among those who, in January, 1ssued 'An Appeal for Law and Order and Com· came across your r ecent statement calling our present mon !)ense,' in dealing with racial problems in Alabama. activities "unwise and untimely." Seldom, if ever, do We expressed understanding that honest convictions in I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas. If racial matters could properly be pursued in the courts I sought to answer all of the criticisms that cross my but urged that decisions ot those courts should in the mean~ desk, my secretaries would he engaged in little else in time be peacefully obeyed. the course of the day, and I would have no time for "Since that time there had been some evidence of in constructive work. But since I feel that you are men of creased forbearance and a willingness to face facts. Re genuine goodwill and your criticisms are sincerely set sponsible citizens have undertaken to work on various forth, I would like to answer your statement in what problems which cause racial friction and unrest. In Bir I hope will he patient and reasonable terms. mingham, recent public events have given indication that we all have opportunity for a new constructive and real I think I should give the reason for my being in Bir· istic approach to racial problems. -

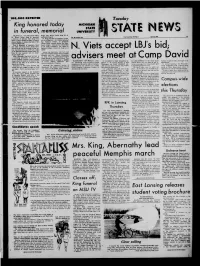

King Honored Today in Fu Nera H Memorial Grieving, Widow East

1 0 0,000 EXPECTKD »1 T u e s d a y King honored today MICHIGAN STATI in fu nera h memorial UNIVERSITY ATLANTA, Ga. (AP)--The church where King's sons, Martin Luther King III, 10, East Lansing, Michigan April 9,1968 10c Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. preached and Dexter King, 8. Vol. 60 Number 152 a doctrine of defiance that rang from Dr. King also had two daughters, Yolan shore to shore opened its doors in funeral da, 12, and Bernice, 5. Dr. Gloster indicated silence Monday to receive the body of the that Spelman College, an all-female m a rt y re d N e g r o idol. college whose campus adjoins the More Tens of thousands of mourners, black house campus, would grant scholarships and while and from every social level, to Dr. King’s daughters. The chapel at b i d Spelman College is where Dr. King lay in N . Viets accept arrived in the city of his birth for the fun eral. Services will be at 10:30 a.m. today repose. at the Ebenezer Baptist Church where Dr. Among the dignitaries who have said King, 39. was co-pastor with his father they will attend the funeral are Sen. Robert the past eight years. Kennedy and Gov. Nelson Rockefeller Other thousands filed past his bier in of New York, Undersecretary-General advisers meet at Cam p David a sorrowing procession of tribute that Ralph Bunche of the United Nations, New wound endlessly toward a quiet campus York M a y o r John V. -

Learning from History the Nashville Sit-In Campaign with Joanne Sheehan

Building a Culture of Peace Forum Learning From History The Nashville Sit-In Campaign with Joanne Sheehan Thursday, January 12, 2017 photo: James Garvin Ellis 7 to 9 pm (please arrive by 6:45 pm) Unitarian Universalist Church Free and 274 Pleasant Street, Concord NH 03301 Open to the Public Starting in September, 1959, the Rev. James Lawson began a series of workshops for African American college students and a few allies in Nashville to explore how Gandhian nonviolence could be applied to the struggle against racial segregation. Six months later, when other students in Greensboro, NC began a lunch counter sit-in, the Nashville group was ready. The sit- As the long-time New in movement launched the England Coordinator for Student Nonviolent Coordinating the War Resisters League, and as former Chair of War James Lawson Committee, which then played Photo: Joon Powell Resisters International, crucial roles in campaigns such Joanne Sheehan has decades as the Freedom Rides and Mississippi Freedom Summer. of experience in nonviolence training and education. Among those who attended Lawson nonviolence trainings She is co-author of WRI’s were students who would become significant leaders in the “Handbook for Nonviolent Civil Rights Movement, including Marion Barry, James Bevel, Campaigns.” Bernard Lafayette, John Lewis, Diane Nash, and C. T. Vivian. For more information please Fifty-six years later, Joanne Sheehan uses the Nashville contact LR Berger, 603 496 1056 Campaign to help people learn how to develop and participate in strategic nonviolent campaigns which are more The Building a Culture of Peace Forum is sponsored by Pace e than protests, and which call for different roles and diverse Bene/Campaign Nonviolence, contributions. -

UBIQUS Document

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND CULTURE Civil Rights History Project Smithsonian Institute's National Museum of African American History & Culture and the Library of Congress, 2011 Reverend C.T. Vivian oral history interview conducted by Taylor Branch in Atlanta, Georgia, March 29, 2011 Irvine, CA Ubiqus Reporting, Inc. New York, NY (949) 477 4972 (212) 227 7440 www.ubiqus.com NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY & CULTURE 2 Civil Rights History Project Line# Timecode Quote 1 [START AFC2010039_CRHP0006_MV1.WMV] 2 [crosstalk] 3 01:00:00 REVEREND C.T. VIVIAN: --When you're 4 talking. 5 INTERVIEWER: Oh, yes. 6 REVEREND VIVIAN: Excuse me. 7 INTERVIEWER: Oh, yes. 8 REVEREND VIVIAN: But there were 9 three of them. But by the way, did 10 you know this story is-- 11 [break in audio] 12 INTERVIEWER: They're in Nashville? 13 01:00:09 REVEREND VIVIAN: Mm-hmm. 14 INTERVIEWER: No. Why? 15 REVEREND VIVIAN: And there's about 16 15 of them--there used to be about 15 17 of them, 12 to 15. 18 INTERVIEWER: Uh-huh. 19 REVEREND VIVIAN: Is because they 20 were looking for the center of 21 population in the United States. 22 INTERVIEWER: Uh-huh. 23 01:00:21 REVEREND VIVIAN: Right, and it was a 24 part of the great Sunday school 25 movement in the country, right? NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY & CULTURE 3 Civil Rights History Project Line# Timecode Quote 26 INTERVIEWER: Uh-huh. 27 REVEREND VIVIAN: And that was the 28 01:00:33 closest one where they could get real 29 railroad and get the materials out to 30 every place in the country. -

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

CASE STUDY The Montgomery Bus Boycott What objectives, targets, strategies, demands, and rhetoric should a nascent social movement choose as it confronts an entrenched system of white supremacy? How should it make decisions? Peter Levine December 2020 SNF Agora Case Studies The SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins University offers a series of case studies that show how civic and political actors navigated real-life challenges related to democracy. Practitioners, teachers, organizational leaders, and trainers working with civic and political leaders, students, and trainees can use our case studies to deepen their skills, to develop insights about how to approach strategic choices and dilemmas, and to get to know each other better and work more effectively. How to Use the Case Unlike many case studies, ours do not focus on individual leaders or other decision-makers. Instead, the SNF Agora Case Studies are about choices that groups make collectively. Therefore, these cases work well as prompts for group discussions. The basic question in each case is: “What would we do?” After reading a case, some groups role-play the people who were actually involved in the situation, treating the discussion as a simulation. In other groups, the participants speak as themselves, dis- cussing the strategies that they would advocate for the group described in the case. The person who assigns or organizes your discussion may want you to use the case in one of those ways. When studying and discussing the choices made by real-life activists (often under intense pres- sure), it is appropriate to exhibit some humility. You do not know as much about their communities and circumstances as they did, and you do not face the same risks.