The Magic Lantern Gazette

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Victorian Photography

THE ART OF VICTORIAN Dr. Laurence Shafe [email protected] PHOTOGRAPHY www.shafe.uk The Art of Victorian Photography The invention and blossoming of photography coincided with the Victorian era and photography had an enormous influence on how Victorians saw the world. We will see how photography developed and how it raised issues concerning its role and purpose and questions about whether it was an art. The photographic revolution put portrait painters out of business and created a new form of portraiture. Many photographers tried various methods and techniques to show it was an art in its own right. It changed the way we see the world and brought the inaccessible, exotic and erotic into the home. It enabled historic events, famous people and exotic places to be seen for the first time and the century ended with the first moving images which ushered in a whole new form of entertainment. • My aim is to take you on a journey from the beginning of photography to the end of the nineteenth century with a focus on the impact it had on the visual arts. • I focus on England and English photographers and I take this title narrowly in the sense of photographs displayed as works of fine art and broadly as the skill of taking photographs using this new medium. • In particular, • Pre-photographic reproduction (including drawing and painting) • The discovery of photography, the first person captured, Fox Talbot and The Pencil of Light • But was it an art, how photographers created ‘artistic’ photographs, ‘artistic’ scenes, blurring, the Pastoral • The Victorian -

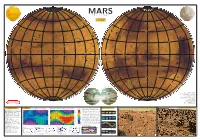

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

"Alfred Stieglitz: Known and Unknown" on View at the National

Office of Press and Public Information Fourth Street and Constitution Av enue NW Washington, DC Phone: 202-842-6353 Fax: 202-789-3044 www.nga.gov/press Release Date: May 20, 2002 "Alfred Stieglitz: Known and Unknown" On View at the National Gallery of Art, June 2 - September 2, 2002 Provides New Insights into the 50-Year Career of This Seminal Artist Washington, DC--Alfred Stieglitz has been renowned for his introduction of modern European art to America and for his support of contemporary American artists, but he was first and foremost a photographer. His photographs, which span more than five decades from the 1880s through the 1930s, are widely celebrated as some of the most compelling ever made. Alfred Stieglitz: Known and Unknown, on view at the National Gallery of Art West Building June 2 through September 2, 2002, presents 102 of Stieglitz's photographs from the National Gallery's collection. Encompassing the full range and evolution of his art, the exhibition includes many works that have not been exhibited in the last fifty years. It highlights less well-known images in order to demonstrate how they expand our understanding of the development of his art and his contributions to 20th-century photography. The exhibition, which is the culmination of a multi-year project on Stieglitz at the National Gallery, also celebrates the publication of Alfred Stieglitz: The Key Set, a definitive study of this seminal figure in the history of photography. Consisting of 1,642 photographs, the key set of Stieglitz's photographs was donated to the National Gallery by Georgia O'Keeffe in 1949 and 1980 and contains the finest example of every mounted print that was in Stieglitz's possession at the time of his death. -

Professionalizing Science and Engineering Education in Late- Nineteenth Century America Paul Nienkamp Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2008 A culture of technical knowledge: professionalizing science and engineering education in late- nineteenth century America Paul Nienkamp Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Other History Commons, Science and Mathematics Education Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Nienkamp, Paul, "A culture of technical knowledge: professionalizing science and engineering education in late-nineteenth century America" (2008). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 15820. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/15820 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A culture of technical knowledge: Professionalizing science and engineering education in late-nineteenth century America by Paul Nienkamp A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: History of Technology and Science Program of Study Committee: Amy Bix, Co-major Professor Alan I Marcus, Co-major Professor Hamilton Cravens Christopher Curtis Charles Dobbs Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2008 Copyright © Paul Nienkamp, 2008. All rights reserved. 3316176 3316176 2008 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii ABSTRACT v CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION – SETTING THE STAGE FOR NINETEENTH CENTURY ENGINEERING EDUCATION 1 CHAPTER 2. EDUCATION AND ENGINEERING IN THE AMERICAN EAST 15 The Rise of Eastern Technical Schools 16 Philosophies of Education 21 Robert Thurston’s System of Engineering Education 36 CHAPTER 3. -

Crater Ice Deposits Near the South Pole of Mars Owen William Westbrook

Crater Ice Deposits Near the South Pole of Mars by Owen William Westbrook Submitted to the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Earth and Planetary Sciences at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2009 © Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2009. All rights reserved. A uth or ........................................ Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences May 22, 2009 Certified by . Maria T. Zuber E. A. Griswold Professor of Geophysics Thesis Supervisor 6- Accepted by.... ...... ..... ........................................... Daniel Rothman Professor of Geophysics Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences MASSACHUSETTS INSTWITE OF TECHNOLOGY JUL 2 0 2009 ARCHIES LIBRARIES Crater Ice Deposits Near the South Pole of Mars by Owen William Westbrook Submitted to the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences on May 22, 2009, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Earth and Planetary Sciences Abstract Layered deposits atop both Martian poles are thought to preserve a record of past climatic conditions in up to three km of water ice and dust. Just beyond the extent of these south polar layered deposits (SPLD), dozens of impact craters contain large mounds of fill material with distinct similarities to the main layered deposits. Previously identified as outliers of the main SPLD, these deposits could offer clues to the climatic history of the Martian south polar region. We extend previous studies of these features by cataloging all crater deposits found near the south pole and quantifying the physical parameters of both the deposits and their host craters. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

In Pdf Format

lós 1877 Mik 88 ge N 18 e N i h 80° 80° 80° ll T 80° re ly a o ndae ma p k Pl m os U has ia n anum Boreu bal e C h o A al m re u c K e o re S O a B Bo l y m p i a U n d Planum Es co e ria a l H y n d s p e U 60° e 60° 60° r b o r e a e 60° l l o C MARS · Korolev a i PHOTOMAP d n a c S Lomono a sov i T a t n M 1:320 000 000 i t V s a Per V s n a s l i l epe a s l i t i t a s B o r e a R u 1 cm = 320 km lkin t i t a s B o r e a a A a A l v s l i F e c b a P u o ss i North a s North s Fo d V s a a F s i e i c a a t ssa l vi o l eo Fo i p l ko R e e r e a o an u s a p t il b s em Stokes M ic s T M T P l Kunowski U 40° on a a 40° 40° a n T 40° e n i O Va a t i a LY VI 19 ll ic KI 76 es a As N M curi N G– ra ras- s Planum Acidalia Colles ier 2 + te . -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse. -

Geography and Vision

Geography and Vision Vision and visual imagery have always played a central role in geographical under- standing, and geographical description has traditionally sought to present its audience with rich and compelling visual images, be they the elaborate cosmo- graphic images of seventeenth century Europe or the computer and satellite imagery of modern geographical information science. Yet the significance of images goes well beyond the mere transcription of spatial and environmental facts and today there is a marked unease among some geographers about their discipline’s association with the pictorial. The expressive authority of visual images has been subverted, shifting attention from the integrity of the image itself towards the expression of truths that lie elsewhere than the surface. In Geography and Vision leading geographer Denis Cosgrove provides a series of personal reflections on the complex connections between seeing, imagining and representing the world geographically. In a series of eloquent and original essays he draws upon pictorial images – including maps, sketches, cartoons, paintings, and photographs – to explore and elaborate upon the many and varied ways in which the vast and varied earth, and at times the heavens beyond, have been both imagined and represented as a place of human habitation. Ranging historically from the sixteenth century to the present day, the essays include reflections upon geographical discovery and Renaissance landscape; urban cartography and utopian visions; ideas of landscape and the shaping of America; widerness and masculinity; conceptions of the Pacific; and the imaginative grip of the Equator. Extensively illustrated, this engaging work reveals the richness and complexity of the geographical imagination as expressed over the past five centuries. -

Mintie, Portrait on the Move

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: Katherine Mintie, “A Portrait on the Move: Photography Literature and Transatlantic Exchanges in the Nineteenth Century,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.9729. A Portrait on the Move: Photography, Literature, and Transatlantic Exchanges in the Nineteenth Century Katherine Mintie, John R. and Barbara Robinson Family Curatorial Fellow in Photography, Harvard Art Museums As a fellow in the Conservation Division of the Library of Congress during the summer of 2015, I worked with Adrienne Lundgren, senior conservator of photographs, on a project to catalogue the photographs tipped into nineteenth- and early twentieth-century photography manuals and periodicals in the library collections. We came across numerous rare and Research Note–worthy photographs, but I will focus here on two versions of a photograph both titled Portraitstudie (figs. 1, 2). Although the portrait itself is typical of the era, it caught my attention because it was one of several prints that appeared in photography periodicals published on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. The print was featured first in the German photography journal Photographische Mitteilungen in November 1871 (fig. 1), and then it reappeared eight months later to United States readers in The Philadelphia Photographer (fig. 2). The transatlantic crossing of this print (and others like it) led me to reconsider two significant features of histories of early photography in the United States: their national focus and emphasis on origins. Figs. 1. 2. Loescher & Petsch (negative)/J. B. Obernetter (print), Portraitstudie in Photographische Mitteilungen, November 1871 (left), and The Philadelphia Photographer, July 1872 (right). -

08Keultjes Final

Dagmar Keultjes Let’s Talk about the Weather! Negative Manipulation Techniques Used to Produce Atmosphere in Landscape Photography 1850–1900 Lecture on November 22, 2013 on the occasion of the symposium “Inspirations – Interactions: Pictorialism Reconsidered” Thank you for the invitation and for making pictures from the Museum of Photography’s Juhl Collection available, enabling me to include some landscape photographs in the presentation. Although the emphasis of the Juhl collection is on portrait photography, there are 32 landscape photographs with sky. Striking is that only two of these photographs don’t depict clouds, from which may already be understood that the representation of clouds is of particular interest to photography. A. Böhmer (photographer); Rudolph Dührkoop (printer), Sheep at Pasture, Platinum print, 1897, 15.6 x 21.4 cm, Ernst Juhl Collection, Kunstbibliothek Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Id. Nr. 1910,150 William Boyd Post, Bermuda Clouds, Platinum print, 1893-1903, 13.7 x 21.3 cm, Ernst Juhl Collection, Kunstbibliothek Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Id.Nr. 1915,258 The two photographs from the collection shown here originated in the same period: the Sheep at Pasture in 1897, the Bermuda Clouds between 1893–1903. The first image shows a pastoral scene: On the left of the image, three sheep graze in front of a small shrub. In front of them a small path divides the image diagonally into two halves. The horizon line is high, set approximately on the line of the golden ratio. The focal depth decreases towards the horizon. The sky is completely cloudless, although it becomes gradually lighter towards the horizon, as if a light source were concealed there, which imparts depth to the firmament. -

Color Photography

Class ^.n\^>4 Book JfeB PRESENTED BY Scanned from the collections of The Library of Congress AUDIO-VISUAL CONSERVATION at Tht LIBRARY of CONGRESS * or Packard Campus for Audio Visual Conservation www.loc.gov/avconservation Motion Picture and Television Reading Room www.loc.gov/rr/mopic Recorded Sound Reference Center www.loc.gov/rr/record COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY A LIST OF REFERENCES IN THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY COMPILED BY WILLIAM BURT GAMBLE Chief of the Science and Technology Division WITH INTRODUCTION BY E. J. WALL Associate Editor of "American Photography'' NEW YORK 1924 / COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY A LIST OF REFERENCES IN THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY WILLIAM BURT GAMBLE Chief of the Science and Technology Division WITH INTRODUCTION BY E. J. WALL Associate Editor of "American Photography" NEW YORK 1924 NOTE This list includes books and periodical articles available in the Reference Depart- ment of The New York Public Library on June 1, 1924. They may be consulted in the Central Building at Fifth Avenue and Forty- second Street. No attempt has been made to cite references to patent records. REPRINTED OCTOBER 1924 FROM THE BULLETIN OF THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY JUNE. JULY, AUGUST AND SEPTEMBER. 1924 PRINTED AT THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY form plSS [x-29-24 3c] COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY A LIST OF REFERENCES IN THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY INTRODUCTION IT is interesting to note that a print in the approximate colors of nature was obtained before photography, as we now understand it, had become an accomplished fact. J. T. Seebeck sent to the poet Goethe a note: "On the chemical action of light and colored illumination," in which he described the reproduction of a spectrum in colors on damp silver chloride.