T?Gtozz7 USAF IOGISTIC PI,ANS and POLICIES - I : Appru,Ieu for in , Pllblti RELEASE It SOUTHEAST ASIA Ld;;'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(1I?I - 1Iii ): the >TRATEQ10 S1GNJF8QANQE ©F Om Muu BAY TH[ and Mm

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE ACADEMY BAMU BAY REVISITED (1i?i - 1iii ): THE >TRATEQ10 S1GNJF8QANQE ©F Om mUU BAY TH[ AND mm. BY CAPTAIN JUAN A. DE LEON PN (GSC) NOVEMBER 1989 A SUB-THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES II PREFACF AND ACKNOWLEDGMENT Southeast Asia is a region fast becoming the center stage of the 21st Century. One historian said that "the Mediterranean is the past, Europe is the present and the Asia-Pacific Region is the future." The future is now! This sub-thesis deals with contemporary issues now determining the future of the region going into the year 2000. Soviet attention was refocused on the Asia-Pacific region after Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev made his historic speech at Vladivostock on 28 July 1986. Since then developments have gone on at a pace faster than expected. The Soviets have withdrawn from Afghanistan. Then in September 1988, Gorbachev spelled out in detail his Vladivostock initiative through his Krasnoyarsk speech and called on major powers, the US, China and Japan, to respond to his peace offensives. He has offered to give up the Soviet presence in Cam Ranh if the US did likewise at Subic and Clark in the Philippines. To some it may appear attractive, while others consider that it is like trading "a pawn for a queen". This sub-thesis completes my ten-month stay in a very progressive country, Australia. I was fortunate enough having been given the chance to undertake a Master of Defence Studies Course (MDef Studies) at the University College, University of New South Wales, Australian Defence Force Academy upon the invitation of the Australian Government. -

Survey on Socio-Economic Development Strategy for the South-Central Coastal Area in Vietnam

Survey on Socio-Economic Development Strategy for the South-Central Coastal Area in Vietnam Final Report October 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY(JICA) Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. KRI International Corp. 1R Pacet Corp. JR 12-065 Dak Lak NR-26 Khanh Hoa PR-2 PR-723 NR-1 NR-27 NR-27 NR-27B Lam Dong NR-27 Ninh Thuan NR-20 NR-28 NR-1 NR-55 Binh Thuan Legend Capital City City NR-1 Railway(North-South Railway) National Road(NR・・・) NR-55 Provincial Road(PR・・・) 02550 75 100Km Study Area(Three Provinces) Location Map of the Study Area Survey on Socio-Economic Development Strategy for the South-Central Coastal Area in Vietnam Survey on Socio-Economic Development Strategy for the South-Central Coastal Area in Vietnam Final Report Table of Contents Page CHAPTER 1 OBJECTIVE AND STUY AREA .............................................................. 1-1 1.1 Objectives of the Study ..................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Study Schedule ................................................................................................. 1-1 1.3 Focus of Regional Strategy Preparation ........................................................... 1-2 CHAPTER 2 GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDY AREA .................. 2-1 2.1 Study Area ......................................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Outline of the Study Area ................................................................................. 2-2 2.3 Characteristics of Ninh Thuan Province -

Chapter 7 Hydrogeology

CHAPTER 7 HYDROGEOLOGY The Study on Groundwater Development in the Rural Provinces of the Southern Coastal Zone in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam Final Report - Supporting - Chapter 7 Hydrogeology CHAPTER 7 HYDROGEOLOGY 7.1 Hydro-geological Survey 7.1.1 Purpose of Survey The hydrogeological survey was conducted to know the geomorphology, the hydrogeology and the distribution and quantities of surface water (rivers, pond, swamps, springs etc.) in the targeted 24 communes. 7.1.2 Survey Method The Study Team conducted the survey systematically with following procedure. a) Before visiting each target commune, the Study Team roughly grasp the hydrogeological images (natural condition, geomorphology, geology, resource of water supply facilities, water quality of groundwater and surface water) of the Study Area using the result of review, analysis of the existing data and the remote sensing analysis. b) Interview on the distribution of main surface water (the location and quantity), main water resources in the 24 target communes. c) Verification of the interview results in the site and acquisition of the location data using handy GPS and simple water quality test equipments. 7.1.3 The Survey Result The field survey conducted from 25 June 2007 to 26 July 2007. Phu Yen, Khanh Hoa and Nin Thuan provinces were in dry season, and Binh Thuan was in rainy season. The each survey result was shown in data sheets with tabular forms for identified surface waters (refer to annex). The results are summarized to from Table 7.1.1 to Table 7.1.24 by every target commune. The main outputs of the survey result are as follows: a. -

Motzer, Lawrence R., Jr. OH1486

Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of an Oral History Interview with LAWRENCE R. MOTZER, JR. Security Forces Officer, U.S. Air Force, Vietnam War 2011 OH 1486 OH 1486 Motzer Jr., Lawrence R., (b.1952). Oral History Interview, 2011. Approximate length: 1 hour 40 minutes Contact WVM Research Center for access to original recording. Abstract: Lawrence R. Motzer, Jr. an Eau Claire, Wisconsin native discusses his service during the Vietnam War as a security forces officer in the Air Force as well as his experience returning home, and his career in the military which took him to Germany, Guam and Korea. Motzer enlisted in the Air Force in his senior year of high school and went to basic training in 1971. He comments on his father’s service in World War II and his patriotism as reasons for joining. Motzer describes his first impressions of Vietnam, the living and working conditions on the base at Cam Ranh Bay, and his assignment as base security guard. He discusses substance abuse, particularly heroin, by other service members and the effects that it had on them. Motzer mentions temporary duty assignments at different bases in Vietnam including Tan Son Nhut Airbase in Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City), experiences of going off-base, and seeing exchanges of North and South Vietnamese prisoners. He talks returning to Wisconsin at the end of his tour and from there being assigned to Whiteman Air Force Base. Motzer describes his various tours of duty in Germany, Guam and Korea before being discharged in 1988. He returned to Eau Claire the same year and briefly talks about his life since leaving the military. -

Maritime Issues in the East and South China Seas

Maritime Issues in the East and South China Seas Summary of a Conference Held January 12–13, 2016 Volume Editors: Rafiq Dossani, Scott Warren Harold Contributing Authors: Michael S. Chase, Chun-i Chen, Tetsuo Kotani, Cheng-yi Lin, Chunhao Lou, Mira Rapp-Hooper, Yann-huei Song, Joanna Yu Taylor C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/CF358 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2016 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover image: Detailed look at Eastern China and Taiwan (Anton Balazh/Fotolia). Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Disputes over land features and maritime zones in the East China Sea and South China Sea have been growing in prominence over the past decade and could lead to serious conflict among the claimant countries. -

Preparing the Ban Sok–Pleiku Power Transmission Project in the Greater Mekong Subregion (Financed by the Japan Special Fund)

Regional Technical Assistance Report Project Number: 41450 August 2008 Preparing the Ban Sok–Pleiku Power Transmission Project in the Greater Mekong Subregion (Financed by the Japan Special Fund) The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s members, Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 31 July 2008) Lao PDR Currency Unit – kip (KN) KN1.00 = $0.00012 $1.00 = KN8,657 Viet Nam Currency Unit – dong (D) D1.00 = $0.00006 $1.00 = D16,613 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank EdL – Electricité du Laos EIA – Environmental Impact Assessment EVN – Vietnam Electricity GMS – Greater Mekong Subregion IEE – initial environmental examination kV – kilovolt Lao PDR – Lao People’s Democratic Republic MW – megawatt NTC – National Transmission Company O&M – operation and maintenance PPA – power purchase agreement TA – technical assistance TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE CLASSIFICATION Targeting Classification – General intervention Sector – Energy Subsector – Transmission and distribution Themes – Sustainable economic growth, private sector development, regional cooperation Subthemes – Fostering physical infrastructure development, public– private partnership, crossborder infrastructure NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. Vice-President C. Lawrence Greenwood, Jr., Operations 2 Director General A. Thapan, Southeast Asia Department (SERD) Director J. Cooney, Infrastructure Division, SERD Team leader X. Humbert, Senior Energy Specialist, -

Air Force Women in the Vietnam War by Jeanne M

Air Force Women in the Vietnam War By Jeanne M. Holm, Maj. Gen., USAF (Ret) and Sarah P. Wells, Brig. Gen. USAF NC (Ret) At the time of the Vietnam War military women Because women had no military obligation, in the United States Air Force fell into three either legal or implied, all who joined the Air categories:female members of the Air Force Nurse Force during the war were true volunteers in Corps (AFNC) and Bio-medical Science Corps every sense. Most were willing to serve (BSC), all of whom were offlcers. All others, wherever they were needed. But when the first offlcers and en-listed women, were identified as American troops began to deploy to the war in WAF, an acronym (since discarded) that stood for Vietnam, the Air Force had no plans to send its Women in the Air Force. In recognition of the fact military women. It was contemplated that all that all of these women were first and foremost USAF military requirements in SEA would be integral members of the U.S. Air Force, the filled by men, even positions traditionally authors determined that a combined presentation considered “women’s” jobs. This was a curious of their participation in the Vietnam War is decision indeed considering the Army Air appropriate. Corps’ highly successful deployment of thousands of its military women to the Pacific When one recalls the air war in Vietnam, and Southeast Asia Theaters of war during visions of combat pilots and returning World War II. prisoners of war come easily to mind. Rarely do images emerge of the thousands of other When the U.S. -

Navy and Coast Guard Ships Associated with Service in Vietnam and Exposure to Herbicide Agents

Navy and Coast Guard Ships Associated with Service in Vietnam and Exposure to Herbicide Agents Background This ships list is intended to provide VA regional offices with a resource for determining whether a particular US Navy or Coast Guard Veteran of the Vietnam era is eligible for the presumption of Agent Orange herbicide exposure based on operations of the Veteran’s ship. According to 38 CFR § 3.307(a)(6)(iii), eligibility for the presumption of Agent Orange exposure requires that a Veteran’s military service involved “duty or visitation in the Republic of Vietnam” between January 9, 1962 and May 7, 1975. This includes service within the country of Vietnam itself or aboard a ship that operated on the inland waterways of Vietnam. However, this does not include service aboard a large ocean- going ship that operated only on the offshore waters of Vietnam, unless evidence shows that a Veteran went ashore. Inland waterways include rivers, canals, estuaries, and deltas. They do not include open deep-water bays and harbors such as those at Da Nang Harbor, Qui Nhon Bay Harbor, Nha Trang Harbor, Cam Ranh Bay Harbor, Vung Tau Harbor, or Ganh Rai Bay. These are considered to be part of the offshore waters of Vietnam because of their deep-water anchorage capabilities and open access to the South China Sea. In order to promote consistent application of the term “inland waterways”, VA has determined that Ganh Rai Bay and Qui Nhon Bay Harbor are no longer considered to be inland waterways, but rather are considered open water bays. -

Weather Diary Cam Ranh Bay Airbase, Republic of Vietnam Nov

Weather Diary Cam Ranh Bay Airbase, Republic of Vietnam Nov. 28, 1968 to Sept. 26, 1969. By Joel Rosenbaum Former USAF weather officer 111 Malibu Drive Eatontown, New Jersey 07724 Introduction As a USAF weather officer stationed at Cam Ranh Bay Airbase, South Vietnam from October 1968 to October 1969, I kept a daily weather diary briefly describing each day's weather, including unusual weather activity and the probable cause. I thought I might use the data in the diary for an advanced degree in meteorology. Instead the diary was tucked away in a drawer for many years. Since there is some interest in this information I am sharing this material with the USAF History Office, Texas A&M University Dept of Meteorology and the Vietnam archives of Texas Tech. University. I have included maps, a climatic summary, and a brief discussion of the climate of Vietnam. I have also included photos to illustrate the diary. As the Russians vacate Cam Ranh Bay there is renewed American interest in using the base for Naval and Air units. So the information in this dairy may be useful in the near future. The Vietnamese were once dominated by the Chinese and even fought a short but brutal border war with them in 1979. They usually seek the friendship of a larger power to keep the Chinese out of Vietnam. It would therefore be possible for the Vietnamese allow the American military some type of usage of Cam Ranh Bay in the future. Educational Background I received a BS in agriculture from Rutgers College of Agriculture and Environmental Science (now Cook College) in 1966. -

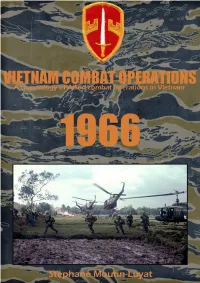

1966 Vietnam Combat Operations

VIETNAM COMBAT OPERATIONS – 1966 A chronology of Allied combat operations in Vietnam 1 VIETNAM COMBAT OPERATIONS – 1966 A chronology of Allied combat operations in Vietnam Stéphane Moutin-Luyat – 2009 distribution unlimited Front cover: Slicks of the 118th AHC inserting Skysoldiers of the 173d Abn Bde near Tan Uyen, Bien Hoa Province. Operation DEXTER, 4 May 1966. (118th AHC Thunderbirds website) 2 VIETNAM COMBAT OPERATIONS – 1966 A chronology of Allied combat operations in Vietnam This volume is the second in a series of chronologies of Allied headquarters: 1st Cav Div. Task organization: 1st Bde: 2-5 combat operations conducted during the Vietnam War from Cav, 1-8 Cav, 2-8 Cav, 1-9 Cav (-), 1-12 Cav, 2-19 Art, B/2-17 1965 to 1973, interspersed with significant military events and Art, A/2-20 Art, B/6-14 Art. 2d Bde: 1-5 Cav, 2-12 Cav, 1-77 augmented with a listing of US and FWF units arrival and depar- Art. Execution: The 1st Bde launched this operation north of ture for each months. It is based on a chronology prepared for Route 19 along the Cambodian border to secure the arrival of the Vietnam Combat Operations series of scenarios for The the 3d Bde, 25th Inf Div. On 4 Jan, the 2d Bde was committed to Operational Art of War III I've been working on for more than conduct spoiling attacks 50 km west of Kontum. Results: 4 three years, completed with additional information obtained in enemy killed, 4 detained, 6 US KIA, 41 US WIA. -

Vietnam Is Wonderful Destination Vietnam Has Exerted Itself to Be a Favorite Destination of More and More Tourists

Vietnam is Wonderful Destination Vietnam has exerted itself to be a favorite destination of more and more tourists. There’s a Hanoi elegant with friendly people, a Sapa with colourful-dressed minorities, a Halong Bay with amazing caves listed on UNESCO World Heritage. There’s a Hue romantic with palace and rain, a tranquil Hoi An where you can have clothes made in one day, a Danang dynamic by Han river. There’s a Nha Trang with best bays of the world, a Saigon busy and modern like Newyork, a Mekong-delta with fascinating floating market. The North, Centre, and South of Vietnam all bear a deep cultural trace, which remains in tourists’ memories for years. Lying on the east of Indochina Peninsula with a distance of 1650 km from south to north, Vietnam is one of the most romantic and naturally beautiful destinations in the world. The diverse natural environment, geography, history, and culture have created a great potential for the tourism, that is wonderful destination for tourists. Moreover, foreign tourists can get Vietnam visa on arrival online easily. 1. Ha Long Bay - Quang Ninh Looking down from above, Ha Long Bay as a huge picture of hydraulic wear extremely lively. Thousands of islands bobbing on the waves of shimmering, both boast spectacular but also very soft and graceful and lively. To take the boat in the middle Ha Long Bay with thousands of islands, seemingly lost in a fairy world was petrified. The island is like someone is looking to land - The First Island; island is like a dragon hovering above the water - Hon Rong; island is like a old man sitting fishing - Hon La Vong; and the other two beefy brown sails are turning out to sea waves. -

List of Districts of Vietnam

S.No Province Name of District 1 An Giang Province An Phú 2 An Giang Province Châu Đốc 3 An Giang Province Châu Phú 4 An Giang Province Châu Thành 5 An Giang Province Chợ Mới 6 An Giang Province Long Xuyên 7 An Giang Province Phú Tân 8 An Giang Province Tân Châu 9 An Giang Province Thoại Sơn 10 An Giang Province Tịnh Biên 11 An Giang Province Tri Tôn 12 Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province Bà Rịa 13 Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province Châu Đức 14 Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province Côn Đảo 15 Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province Đất Đỏ 16 Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province Long Điền 17 Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province Tân Thành 18 Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province Vũng Tàu 19 Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province Xuyên Mộc 20 Bắc Giang Province Bắc Giang 21 Bắc Giang Province Hiệp Hòa 22 Bắc Giang Province Lạng Giang 23 Bắc Giang Province Lục Nam 24 Bắc Giang Province Lục Ngạn 25 Bắc Giang Province Sơn Động 26 Bắc Giang Province Tân Yên 27 Bắc Giang Province Việt Yên 28 Bắc Giang Province Yên Dũng 29 Bắc Giang Province Yên Thế 30 Bắc Kạn Province Ba Bể 31 Bắc Kạn Province Bắc Kạn 32 Bắc Kạn Province Bạch Thông 33 Bắc Kạn Province Chợ Đồn 34 Bắc Kạn Province Chợ Mới 35 Bắc Kạn Province Na Rì 36 Bắc Kạn Province Ngân Sơn 37 Bắc Kạn Province Pác Nặm 38 Bạc Liêu Province Bạc Liêu 39 Bạc Liêu Province Đông Hải 40 Bạc Liêu Province Giá Rai 41 Bạc Liêu Province Hòa Bình 42 Bạc Liêu Province Hồng Dân 43 Bạc Liêu Province Phước Long 44 Bạc Liêu Province Vĩnh Lợi 45 Bắc Ninh Province Bắc Ninh 46 Bắc Ninh Province Gia Bình www.downloadexcelfiles.com 47 Bắc Ninh Province Lương Tài 48 Bắc Ninh Province Quế Võ 49 Bắc Ninh Province Thuận