The Tree of Life Design 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Present-Day Veneration of Sacred Trees in the Holy Land

ON THE PRESENT-DAY VENERATION OF SACRED TREES IN THE HOLY LAND Amots Dafni Abstract: This article surveys the current pervasiveness of the phenomenon of sacred trees in the Holy Land, with special reference to the official attitudes of local religious leaders and the attitudes of Muslims in comparison with the Druze as well as in monotheism vs. polytheism. Field data regarding the rea- sons for the sanctification of trees and the common beliefs and rituals related to them are described, comparing the form which the phenomenon takes among different ethnic groups. In addition, I discuss the temporal and spatial changes in the magnitude of tree worship in Northern Israel, its syncretic aspects, and its future. Key words: Holy land, sacred tree, tree veneration INTRODUCTION Trees have always been regarded as the first temples of the gods, and sacred groves as their first place of worship and both were held in utmost reverence in the past (Pliny 1945: 12.2.3; Quantz 1898: 471; Porteous 1928: 190). Thus, it is not surprising that individual as well as groups of sacred trees have been a characteristic of almost every culture and religion that has existed in places where trees can grow (Philpot 1897: 4; Quantz 1898: 467; Chandran & Hughes 1997: 414). It is not uncommon to find traces of tree worship in the Middle East, as well. However, as William Robertson-Smith (1889: 187) noted, “there is no reason to think that any of the great Semitic cults developed out of tree worship”. It has already been recognized that trees are not worshipped for them- selves but for what is revealed through them, for what they imply and signify (Eliade 1958: 268; Zahan 1979: 28), and, especially, for various powers attrib- uted to them (Millar et al. -

FEATURE TYPES Revised 2/2001 Alcove

THE CROW CANYON ARCHAEOLOGICAL CENTER FEATURE TYPES Revised 2/2001 alcove. A small auxiliary chamber in a wall, usually found in pit structures; they often adjoin the east wall of the main chamber and are substantially larger than apertures and niches. aperture. A generic term for a wall opening that cannot be defined more specifically. architectural petroglyph (not on bedrock). A petroglyph in a standing masonry wall.A piece of wall fall with a petroglyph on it should be sent in as an artifact if size permits. ashpit. A pit used primarily as a receptacle for ash removed from a hearth or firepit. In a pit structure, the ash pit is commonly oval or rectangular and is located south of the hearth or firepit. bedrock feature. A feature constructed into bedrock that does not fit any of the other feature types listed here. bell-shaped cist. A large pit whose greatest diameter is substantially larger than the diameter of its opening.A storage function is implied, but the feature may not contain any stored materials, in which case the shape of the pit is sufficient for assigning this feature type. bench surface. The surface of a wide ledge in a pit structure or kiva that usually extends around at least three-fourths of the circumference of the structure and is often divided by pilasters.The southern recess surface is also considered a bench surface segment; each bench surface segment must be recorded as a separate feature. bin: not further specified. An above-ground compartment formed by walling off a portion of a structure or courtyard other than a corner. -

Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts

Guide to Research at Hirsch Library Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts Before researching a work of art from the MFAH collection, the work should be viewed in the museum, if possible. The cultural context and descriptions of works in books and journals will be far more meaningful if you have taken advantage of this opportunity. Most good writing about art begins with careful inspections of the objects themselves, followed by informed library research. If the project includes the compiling of a bibliography, it will be most valuable if a full range of resources is consulted, including reference works, books, and journal articles. Listing on-line sources and survey books is usually much less informative. To find articles in scholarly journals, use indexes such as Art Abstracts or, the Bibliography of the History of Art. Exhibition catalogs and books about the holdings of other museums may contain entries written about related objects that could also provide guidance and examples of how to write about art. To find books, use keywords in the on-line catalog. Once relevant titles are located, careful attention to how those items are cataloged will lead to similar books with those subject headings. Footnotes and bibliographies in books and articles can also lead to other sources. University libraries will usually offer further holdings on a subject, and the Electronic Resources Room in the library can be used to access their on-line catalogs. Sylvan Barnet’s, A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 6th edition, provides a useful description of the process of looking, reading, and writing. -

The Tree of LIFE

The Tree of LIFE ~ 2 ~ ~ 3 ~ ~ 4 ~ Trees of Life. From the highest antiquity trees were connected with the gods and mystical forces in nature. Every nation had its sacred tree, with its peculiar characteristics and attributes based on natural, and also occasionally on occult properties, as expounded in the esoteric teachings. Thus the peepul or Âshvattha of India, the abode of Pitris (elementals in fact) of a lower order, became the Bo-tree or ficus religiosa of the Buddhists the world over, since Gautama Buddha reached the highest knowledge and Nirvâna under such a tree. The ash tree, Yggdrasil, is the world-tree of the Norsemen or Scandinavians. The banyan tree is the symbol of spirit and matter, descending to the earth, striking root, and then re-ascending heavenward again. The triple- leaved palâsa is a symbol of the triple essence in the Universe - Spirit, Soul, Matter. The dark cypress was the world-tree of Mexico, and is now with the Christians and Mahomedans the emblem of death, of peace and rest. The fir was held sacred in Egypt, and its cone was carried in religious processions, though now it has almost disappeared from the land of the mummies; so also was the sycamore, the tamarisk, the palm and the vine. The sycamore was the Tree of Life in Egypt, and also in Assyria. It was sacred to Hathor at Heliopolis; and is now sacred in the same place to the Virgin Mary. Its juice was precious by virtue of its occult powers, as the Soma is with Brahmans, and Haoma with the Parsis. -

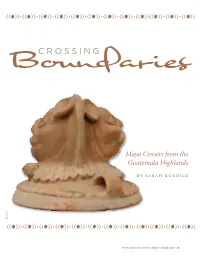

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

Museum of New Mexico

MUSEUM OF NEW MEXICO OFFICE OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDIES ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE MOGOLLON HIGHLANDS: SETTLEMENT SYSTEMS AND ADAPTATIONS edited by Yvonne R. Oakes and Dorothy A. Zamora VOLUME 6. SYNTHESIS AND CONCLUSIONS Yvonne R. Oakes Submitted by Timothy D. Maxwell Principal Investigator ARCHAEOLOGY NOTES 232 SANTA FE 1999 NEW MEXICO TABLE OF CONTENTS Figures............................................................................iii Tables............................................................................. iv VOLUME 6. SYNTHESIS AND CONCLUSIONS ARCHITECTURAL VARIATION IN MOGOLLON STRUCTURES .......................... 1 Structural Variation through Time ................................................ 1 Communal Structures......................................................... 19 CHANGING SETTLEMENT PATTERNS IN THE MOGOLLON HIGHLANDS ................ 27 Research Orientation .......................................................... 27 Methodology ................................................................ 27 Examination of Settlement Patterns .............................................. 29 Population Movements ........................................................ 35 Conclusions................................................................. 41 REGIONAL ABANDONMENT PROCESSES IN THE MOGOLLON HIGHLANDS ............ 43 Background for Studying Abandonment Processes .................................. 43 Causes of Regional Abandonment ............................................... 44 Abandonment Patterns in the Mogollon Highlands -

Michael M. Hobby, June M. Hobby, and Troy J

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 8 Number 1 Article 12 1996 Michael M. Hobby, June M. Hobby, and Troy J. Smith. Angular Chronology: The Precolumbian Dating of Ancient America V. Garth Norman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Norman, V. Garth (1996) "Michael M. Hobby, June M. Hobby, and Troy J. Smith. Angular Chronology: The Precolumbian Dating of Ancient America," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol8/iss1/12 This Historical and Cultural Studies is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Author(s) V. Garth Norman Reference FARMS Review of Books 8/1 (1996): 112–17. ISSN 1099-9450 (print), 2168-3123 (online) Abstract Review of Angular Chronology: The Precolumbian Dating of Ancient America (1994), by Michael M. Hobby, June M. Hobby, and Troy J. Smith. Michael M. Hobby, June M. Hobby, and Troy J. Smith. Angular Chronology: The Precolumbian Dating of Ancient America. Coto Laurel, Puerto Rico: Zarahemla Foundation, 1994. 81 pp. $6.95 Reviewed by V. Garth Norman This publication by the Zarahemla Foundation (ZF, not to be confused with the Zarahemla Research Foundation), with Michael M . Hobby as director and principal author, purports to enlighten Book of Mormon students by revealing startling di scoveries on the realities of Book of Mormon geography and history. -

Silk Cotton Vs. Bombax Vs. Banyan

Ceiba pentandra Kopok tree, Silk-cotton tree Ta Prohm, Cambodia By Isabel Zucker Largest known specimen in Lal Bagh Gardens in Bangalore, India. http://scienceray.com/biology/botany/amazing-trees-from-around-the-world-the-seven-wonder-trees/ Ceiba pentandra Taxonomy • Family: Malvaceae • Sub family: Bombacaceae -Bombax spp. in same family - much online confusion as to which tree is primarily in Ta Praham, Cambodia. • Fig(Moraceae), banyan and kapok trees in Ta Praham • Often referred to as a banyan tree, which is quite confusing. Distribution • Originated in the American tropics, natural and human distribution. • Africa, Asia. – Especially Indonesia and Thailand • Indian ocean islands • Ornamental shade tree • Zone – Humid areas, rainforest, dry areas – Mean annual precipitation 60-224 inches per year – Temperatures ranging from 73-80 unaffected by frost – Elevation from 0-4,500 feet – Dry season ranging from 0-6 months Characteristics • Rapidly growing, deciduous • Reaches height up to 200 feet • Can grow 13 feet per year • Diameter up to 9 feet above buttress – Buttress can extend 10 feet from the trunk and be 10 feet tall • large umbrella-shaped canopies emerge above the forest canopy • http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/caribarch/ceiba.htm • Home to many animals – Birds, frogs, insects – Flowers open in the evening, pollinated by bats • Epiphytes grow in branches • Compound leaves with 5-8 lance- shaped leaflets 3-8 inches long • Dense clusters of whitish to pink flowers December to February – 3-6 inch long, elliptical fruits. – Seeds of fruit surrounded by dense, cottony fibers. – Fibers almost pure cellulose, buoyant, impervious to water, low thermal conductivity, cannot be spun. -

Milwaukee County Historical Society

Title: White Family Collection Manuscript Number: Mss-3325 Inclusive Dates: ca. 1925-2009 Quantity: 14.4 cu. ft. Location: WHW, Sh. B004-B006 (14.0 cu. ft.) RC21A, Sh. 005 (0.4 cu. ft.) Abstract: The White Family consisted of husband and wife Joseph Charles White and Nancy Metz White, and their twin daughters Michele and Jacqueline. Nancy was a local artist who designed and created sculptures constructed out of discarded scrap metal, heating and cooling ventilation pipes, and other recycled items. Originally from Madison, she graduated from UW- Madison with a bachelor’s degree in art education and also did graduate study there. She is primarily noted for creating large-scale outdoor public sculptures, which include Tree of Life in Mitchell Boulevard Park in 2002, Magic Grove in Enderis Park in 2006, Helping Hands at Mead Public Library in Sheboygan, and Fantasy Garden at St. John’s On the Lake. In addition to being a sculptor, Nancy also was an art teacher and the Creative Art Coordinator at Urban Day School Elementary from 1970 to 1978. Joseph C. White was born in 1925 in Michigan. He earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Northwestern University and also served in the Navy during World War II and the Korean conflict. In the 1960s, as Vice President of Inland Steel Products Company, he led the company’s involvement in the pioneering School Construction Systems Development (SCSD) project for California schools. He left Inland Steel and formed his own company, Syncon, to focus on modular construction projects. He was also an adjunct architecture professor at UW- Milwaukee. -

P S Y C H O S O C I a L W E L L B E I N G S E R I

PSYCHOSOCIAL WELLBEING SERIES Tree of Life A workshop methodology for children, young people and adults Adapted by Catholic Relief Services with permission from REPSSI Third Edition for a Global Audience 1 REPSSI is a non-profit organisation working to lessen the devastating social and Catholic Relief Services (CRS) was founded in 1943 by the Catholic Bishops of emotional (psychosocial) impact of poverty, conflict, HIV and AIDS among children the United States to serve World War II survivors in Europe. Since then, we have and youth. It is led by Noreen Masiiwa Huni, Chief Executive Officer. REPSSI’s aim is expanded in size to reach 100 million people annually in over 100 countries on five to ensure that all children have access to stable care and protection through quality continents. psychosocial support. We work at the international, regional and national level in East and Southern Africa. Our mission is to assist impoverished and disadvantaged people overseas, working in the spirit of Catholic social teaching to promote the sacredness of human life The best way to support vulnerable children and youth is within a healthy family and and the dignity of the human person. Catholic Relief Services works in partnership community environment. We partner with governments, development partners, with local, national and international organizations and structures in emergency international organisations and NGOs to provide programmes that strengthen response, agriculture and health, as well as microfinance, water and sanitation, communities’ and families’ competencies to better promote the psychosocial peace and justice, capacity strengthening, and education. Although our mission wellbeing of their children and youth. -

Phylogeny and Biogeography of Ceiba Mill. (Malvaceae, Bombacoideae)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.10.196238; this version posted July 10, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 TITLE PAGE 2 3 Pezzini et al. Evolutionary History of Tropical Dry Forest 4 5 Research article: Phylogeny and biogeography of Ceiba Mill. (Malvaceae, Bombacoideae) 6 7 Flávia Fonseca Pezzini1,2,8, Kyle G. Dexter3, Jefferson G. de Carvalho-Sobrinho4, Catherine A. Kidner1,2, 8 James A. Nicholls5, Luciano P. de Queiroz6, R. Toby Pennington1,7 9 10 1 Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom 11 2 School of Biological Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom 12 3 School of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom. 13 4 Colegiado de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal do Vale do São Francisco, Petrolina, Brazil 14 5 Australian National Insect Collection, CSIRO, Acton, Australia 15 6 Herbario, Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, Feira de Santana, Brazil 16 7 Geography, College of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Exeter, Exeter, United Kingdom 17 8 Corresponding author: [email protected] | 20a Inverleith Row Edinburgh, EH3 5LR, UK 18 19 ABSTRACT 20 The Neotropics is the most species-rich area in the world and the mechanisms that generated and 21 maintain its biodiversity are still debated. This paper contributes to the debate by investigating 22 the evolutionary and biogeographic history of the genus Ceiba Mill. -

Sources of Mythology: National and International

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY & EBERHARD KARLS UNIVERSITY, TÜBINGEN SEVENTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY SOURCES OF MYTHOLOGY: NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL MYTHS PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS May 15-17, 2013 Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany Conference Venue: Alte Aula Münzgasse 30 72070, Tübingen PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, MAY 15 08:45 – 09:20 PARTICIPANTS REGISTRATION 09:20 – 09:40 OPENING ADDRESSES KLAUS ANTONI Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany JÜRGEN LEONHARDT Dean, Faculty of Humanities, Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany 09:40 – 10:30 KEYNOTE LECTURE MICHAEL WITZEL Harvard University, USA MARCHING EAST, WITH A DETOUR: THE CASES OF JIMMU, VIDEGHA MATHAVA, AND MOSES WEDNESDAY MORNING SESSION CHAIR: BORIS OGUIBÉNINE GENERAL COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY AND METHODOLOGY 10:30 – 11:00 YURI BEREZKIN Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, Saint Petersburg, Russia UNNOTICED EURASIAN BORROWINGS IN PERUVIAN FOLKLORE 11:00 – 11:30 EMILY LYLE University of Edinburgh, UK THE CORRESPONDENCES BETWEEN INDO-EUROPEAN AND CHINESE COSMOLOGIES WHEN THE INDO-EUROPEAN SCHEME (UNLIKE THE CHINESE ONE) IS SEEN AS PRIVILEGING DARKNESS OVER LIGHT 11:30 – 12:00 Coffee Break 12:00 – 12:30 PÁDRAIG MAC CARRON RALPH KENNA Coventry University, UK SOCIAL-NETWORK ANALYSIS OF MYTHOLOGICAL NARRATIVES 2 NATIONAL MYTHS: NEAR EAST 12:30 – 13:00 VLADIMIR V. EMELIANOV St. Petersburg State University, Russia FOUR STORIES OF THE FLOOD IN SUMERIAN LITERARY TRADITION 13:00 – 14:30 Lunch Break WEDNESDAY AFTERNOON SESSION CHAIR: YURI BEREZKIN NATIONAL MYTHS: HUNGARY AND ROMANIA 14:30 – 15:00 ANA R. CHELARIU New Jersey, USA METAPHORS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF MYTHICAL LANGUAGE - WITH EXAMPLES FROM ROMANIAN MYTHOLOGY 15:00 – 15:30 SAROLTA TATÁR Peter Pazmany Catholic University of Hungary A PECHENEG LEGEND FROM HUNGARY 15:30 – 16:00 MARIA MAGDOLNA TATÁR Oslo, Norway THE MAGIC COACHMAN IN HUNGARIAN TRADITION 16:00 – 16:30 Coffee Break NATIONAL MYTHS: AUSTRONESIA 16:30 – 17:00 MARIA V.