Transcript of Spoken, Rather Than Written Prose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holocaust Education Teacher Resources Why Teach The

Holocaust Education Teacher Resources Compiled by Sasha Wittes, Holocaust Education Facilitator For Ilana Krygier Lapides, Director, Holocaust & Human Rights Education Calgary Jewish Federation Why Teach The Holocaust? The Holocaust illustrates how silence and indifference to the suffering of others, can unintentionally, serve to perpetuate the problem. It is an unparalleled event in history that brings to the forefront the horrors of racism, prejudice, and anti-Semitism, as well as the capacity for human evil. The Canadian education system should aim to be: democratic, non-repressive, humanistic and non-discriminating. It should promote tolerance and offer bridges for understanding of the other for reducing alienation and for accommodating differences. Democratic education is the backbone of a democratic society, one that fosters the underpinning values of respect, morality, and citizenship. Through understanding of the events, education surrounding the Holocaust has the ability to broaden students understanding of stereotyping and scapegoating, ensuring they become aware of some of the political, social, and economic antecedents of racism and provide a potent illustration of both the bystander effect, and the dangers posed by an unthinking conformity to social norms and group peer pressure. The study of the Holocaust coupled with Canada’s struggle with its own problems and challenges related to anti-Semitism, racism, and xenophobia will shed light on the issues facing our society. What was The Holocaust? History’s most extreme example of anti- Semitism, the Holocaust, was the systematic state sponsored, bureaucratic, persecution and annihilation of European Jewry by Nazi Germany and its collaborators between 1933-1945. The term “Holocaust” is originally of Greek origin, meaning ‘sacrifice by fire’ (www.ushmm.org). -

Essays on Holocaust and Genocide Editor: Colin Tatz

Genocide Perspectives IV Essays on Holocaust and Genocide Editor: Colin Tatz The Australian Institute for Holocaust & Genocide Studies UTSePress 2012 2 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Tatz, Colin Genocide perspectives IV : essays on holocaust and genocide/Colin Tatz. ISBN: 9780987236975 Genocide. Antisemitism. Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945) 304.663 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This volume owes much to Sandra Tatz. It was Sandra who initiated the collection, contacted the contributors, arranged the peer reviews, helped organise the framework, proofed the contents, and designed the layout of this volume. My thanks to Gabrielle Gardiner and Cornelia Cronje at the University of Technology Sydney for this e-book and Agata Mrva-Montoya and Susan Murray-Smith from Sydney University Press for hard copies. Thanks to Konrad Kwiet, Graeme Ward, Winton Higgins, and Rowan Savage for their assistance and to Torunn Higgins for her cover design. Three of the essays are modified, extended and updated versions of articles that have appeared elsewhere, as indicated in their contributions here. We acknowledge Oxford University Press as the publishers of the Michael Dudley and Fran Gale essay; Patterns of Prejudice (UK) for the Ruth Balint paper; and Interstitio (Republic of Moldova) for Shannon Woodcock's essay. Cover design: Torunn Higgins The essays in this volume are refereed. Copyright rests with the individual authors © 2012. 4 CONTENTS Colin Tatz The Magnitude of Genocide 5 Rowan Savage ‘With Scorn and Bias’: Genocidal 21 Dehumanisation -

Censorship and Holocaust Film in the Hollywood Studio System Nancy Copeland Halbgewachs

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Sociology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2012 Censorship and Holocaust Film in the Hollywood Studio System Nancy Copeland Halbgewachs Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/soc_etds Recommended Citation Halbgewachs, Nancy Copeland. "Censorship and Holocaust Film in the Hollywood Studio System." (2012). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/soc_etds/18 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nancy Copeland Halbgewachs Candidate Department of Sociology Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. George A. Huaco , Chairperson Dr. Richard Couglin Dr. Susan Tiano Dr. James D. Stone i CENSORSHIP AND HOLOCAUST FILM IN THE HOLLYWOOD STUDIO SYSTEM BY NANCY COPELAND HALBGEWACHS B.A., Sociology, University of Kansas, 1962 M.A., Sociology, University of Kansas, 1966 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December, 2011 ii DEDICATION In memory of My uncle, Leonard Preston Fox who served with General Dwight D. Eisenhower during World War II and his wife, my Aunt Bonnie, who visited us while he was overseas. My friend, Dorothy L. Miller who as a Red Cross worker was responsible for one of the camps that served those released from one of the death camps at the end of the war. -

Transcript of Spoken, Rather Than Written Prose

https://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Interview with Selma Engel February 12, 1992 RG-50.042*0010 https://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection PREFACE The following oral history testimony is the result of a videotaped interview with Selma Engel, conducted on February 12, 1992 in Bradford, Connecticut on behalf of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The interview is part of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum's collection of oral testimonies. Rights to the interview are held by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The reader should bear in mind that this is a verbatim transcript of spoken, rather than written prose. This transcript has been neither checked for spelling nor verified for accuracy, and therefore, it is possible that there are errors. As a result, nothing should be quoted or used from this transcript without first checking it against the taped interview. https://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection SELMA ENGEL February 12, 1992 Beep. Why don't we start with your arrival in Westerbork and a-- Westerbork? Yeah, and then going on the train to Sobibór. (Clears throat) I came from um, Vught, from the concentration camp, Vught, I came to Westerbork in 194...2, 43, and, uh, uh, when I came there, I found an uncle and my mother was there with the five children, and we came together with these girls that I met, we stayed together with them, and, and a whole bunch of uh, Dutch girls, we stayed always very close together. -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 20 Wild Westerns: Marshals & Gunman 2 Days in the Valley (2 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 24: Redemption 2 Discs (4 Discs) 27 Dresses 4 Movies With Soul 40 Year Old Virgin, The 400 Years of the Telescope 50 Icons of Comedy 5 Action Movies 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 5 Great Movies Rated G 1917 5th Wave, The 1961 U.S. Figure Skating Championships 6 Family Movies (2 Discs) 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) A 8 Mile A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family A.R.C.H.I.E. 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Abandon 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Abduction 10,000 BC About Schmidt 102 Minutes That Changed America Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Absolute Power 11:14 Accountant, The 12 Angry Men Act of Valor 12 Years a Slave Action Films (2 Discs) 13 Ghosts of Scooby-Doo, The: The Action Pack Volume 6 complete series (2 Discs) Addams Family, The 13 Hours Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Brother, The Heritage Adventures in Babysitting 16 Blocks Adventures in Zambezia 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Dally & Spanky 2005 Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 20 Movie Star Films Adventures of Huck Finn, The Hartford Public Library DVD Title List Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. -

Hoose Civility

hoose civility T11(; Modesto Citv Sdhlols Board ot Education tlw countY-\,\'ide "Choose Civility" initiativE' and to encourage and model (ivil behavior. MODESTO CITY SCHOOLS BOARD OF EDUCATION AGENDA BOARD ROOM IN THE STAFF DEVELOPMENT CENTER 1326th REGULAR MEETING July 9, 2012 Period for Public Presentations 6:15 p.m.* In compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, if you need special assistance to participate in this meeting, please contact the Superintendent's office, 576-4141. Notification 48 hours prior to the meeting will enable the District to make reasonable arrangements to ensure accessibility to this meeting. Any writings or documents that are public records and are provided to a majority of the governing board regarding an open session item on this agenda will be made available for public inspection in the District office located at 426 Locust Street during normal business hours. * Times are approximate. Individuals wishing to address an agenda item should plan accordingly. A. INITIAL MATTERS: 5:00 to 5:01 1. Call to Order. 5:01 to 6:00 2. Closed Session. Public comment regarding closed session items will be received before the Board goes into closed session. 1 Conference with Legal Counsel: Pending Litigation; No. Cases: One Stanislaus Superior Court Case No. CV 647498 . .2 Public Employee Appointments: >- Appointment of Directors, Educational Services >- Appointment of Director, Parent and Community Involvement >- Appointment of Principal, 9-12 .3 Conference with District Labor Negotiator: Craig Rydquist regarding employee organizations: Modesto Teachers' Association and California School Employees Association, Chapter No. 007; and Unrepresented Employees (Managers and Administrators) . Regular Meeting July 9, 2012 A. -

PT Barnum and the Transcontinental Railroad

The Saber and Scroll Journal Volume 8, Number 3 • Spring 2020 © 2020 Policy Studies Organization TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome Letter ...................................................................................................... 1 Lew Taylor Reconnecting America: P.T. Barnum and the Transcontinental Railroad ................................................................................................................. 3 Chelsea Tatham Zukowski Soviet Russia’s Reaction to the Nazi Holocaust and the Implications of the Suppression of Jewish Suffering ............................................................... 17 Mike Pratt Tea Table Sisterhood and Rebel Dames: The Contributions of Women Jacobites 1688–1788 .............................................................................. 37 Gina Pittington The Hitler Youth & Communism: The Impacts of a Brainwashed Generation in Post-War Politics in Eastern Germany ...................................... 63 Devin Davis The Effects of the Bolshevik Revolution Of 1917: A Case Study ...................... 81 Mason Krebsbach Reinhard Heydrich and the Development of the Einsatzgruppen, 1938–1942 ............................................................................................................ 99 William E. Brennan Book Review: Tom Chaffin. Revolutionary Brothers: Thomas Jefferson, the Marquis de Lafayette, and the Friendship that Helped Forge Two Nations ............................................................................................................... 115 Peggy Kurkowski -

Sarah Shewchuk

University of Alberta Silence and Voices: Family History and Memorialization in Intergenerational Holocaust Literature by Sarah Shewchuk A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Comparative Literature ©Sarah Shewchuk Fall 2012 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-89901-4 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-89901-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

The Survivor's Hunt for Nazi Fugitives in Brazil: The

THE SURVIVOR’S HUNT FOR NAZI FUGITIVES IN BRAZIL: THE CASES OF FRANZ STANGL AND GUSTAV WAGNER IN THE CONTEXT OF INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE by Kyle Leland McLain A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Charlotte 2016 Approved by: ______________________________ Dr. Heather Perry ______________________________ Dr. Jürgen Buchenau ______________________________ Dr. John Cox ii ©2016 Kyle Leland McLain ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSTRACT KYLE LELAND MCLAIN. The survivor’s hunt for Nazi fugitives in Brazil: the cases of Franz Stangl and Gustav Wagner in the context of international justice (Under the direction of DR. HEATHER PERRY) On April 23, 1978, Brazilian authorities arrested Gustav Wagner, a former Nazi internationally wanted for his crimes committed during the Holocaust. Despite a confirming witness and petitions from West Germany, Israel, Poland and Austria, the Brazilian Supreme Court blocked Wagner’s extradition and released him in 1979. Earlier in 1967, Brazil extradited Wagner’s former commanding officer, Franz Stangl, who stood trial in West Germany, was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. These two particular cases present a paradox in the international hunt to bring Nazi war criminals to justice. They both had almost identical experiences during the war and their escape, yet opposite outcomes once arrested. Trials against war criminals, particularly in West Germany, yielded some successes, but many resulted in acquittals or light sentences. Some Jewish survivors sought extrajudicial means to see that Holocaust perpetrators received their due justice. Some resorted to violence, such as vigilante justice carried out by “Jewish vengeance squads.” In other cases, private survivor and Jewish organizations collaborated to acquire information, lobby diplomatic representatives and draw public attention to the fact that many Nazi war criminals were still at large. -

Make PDF Z Tej Stronie

Truth About Camps | W imię prawdy historycznej (en) https://en.truthaboutcamps.eu/thn/german-camps/concentration-camps-fun/15598,Concentration-camps039-func tionaries-biographical-notes-and-witness-account.html 2021-09-23, 13:49 Concentration camps' functionaries - biographical notes and witness’ account Rudolf Höss, ur. 25 XI 1900, SS-Obersturmbannführer, komendant obozu koncentracyjnego Auschwitz w latach 1940–1943. Po wojnie sądzony przez polski Najwyższy Trybunał Narodowy i skazany na karę śmierci. Wyrok wykonano 16 IV 1947 r. Ze wspomnień R. Hössa: By the will of the Reichsführer SS, Auschwitz became the greatest human extermination centre of all time. When in the summer of 1941 he himself gave me the order to prepare installations at Auschwitz where mass exterminations could take place, and personally to carry out these exterminations, I did not have the slightest idea of their scale or consequences. It was certainly an extraordinary and monstrous order. Nevertheless the reasons behind the extermination program seemed to me right. I did not reflect on it at the time: I had been given an order, and I had to carry it out. […] If the Führer had himself given the order for the “final solution of the Jewish question”, then, for a veteran National-Socialist and even more so for an SS officer, there could be no question of considering its merits. “The Führer commands, we follow”, was never a mere phrase or slogan. It was meant in bitter earnest. Źródło: Commandant of Auschwitz: the autobiography of Rudolf Höss, London 1959, s. 144–145. Na temat swojej roli w zagładzie: Again and again during these confidential conversations [chodzi o przesłuchania w śledztwie – przyp. -

Trauma E Narrazione

Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN Letterature classiche, moderne, comparate e postcoloniali Ciclo: XXIX Settore Concorsuale di afferenza: 10F4 Settore Scientifico disciplinare: L-FIL-LET/14 TITOLO TESI Per-formare il trauma: la narrazione post- traumatica tra i conflitti mondiali e il terrorismo Presentata da: Aureliana Natale Coordinatore Dottorato: Relatore: Prof.ssa Silvia Albertazzi Prof. Massimo Fusillo Correlatore: Prof. Maurizio Ascari Esame finale anno 2017 A Giovannella Fusco Girard 2 What kind of idea are you? Are you the kind that compromises, does deals, accomodates itself to society, aims to find a niche, to survive; or are you the cussed, bloody-minded, ramrod-backed type of damnfool notion that would rather break than sway with the breeze? – The kind that will almost certainly, ninety-nine times out of hundred, be smashed to bits; but, the hundredth time, will change the world. Salman Rushdie, The Satanic Verses 3 Indice Introduzione: Raccontare per immagini: il trauma ‘rimediato’ nella cultura di massa 1. Trauma pop……………………………………………………………………. p. 6 2. Psicoanalisi e letteratura…………………………………………………. p. 16 3. La performance del trauma……………………………………………… p. 22 Prima parte: Dal terrore della guerra alla guerra del terrore 1. Scrivere il trauma della guerra………………………………………. p. 26 2. La nascita di una nuova memoria: testimonianze della Grande Guerra………………………………………………………………………….. p. 32 3. Il mémoire tra ricordo e strumentalizzazione…………………. p. 41 4. Testimonianze dirette…………………………………………………… p. 47 5. Testimoni dalla parte del male ……………………………………… p. 53 6. Testimonianza indiretta: testimoni di testimoni…………….. p. 64 7. Disegnare il silenzio………………………………………………………. p. 84 8. Trappole per topi………………………………………………………….. p. 89 Seconda parte: 9/11: Nuove estetiche post-traumatiche 1. -

Everyday Objects from the Holocaust-PT 2

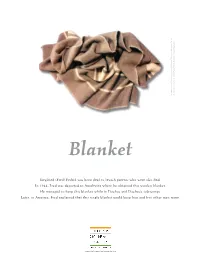

On display at the Washington State Holocaust Education Resource Center. State Holocaust Education Resource Center. Washington On display at the Harve Photo by of Siegfried Fedrid. On loan from the family Bergmann. Blanket Siegfried (Fred) Fedrid was born deaf to Jewish parents who were also deaf. In 1944, Fred was deported to Auschwitz where he obtained this woolen blanket. He managed to keep this blanket while in Dachau and Dachau’s sub-camps. Later, in America, Fred explained that this single blanket could keep him and five other men warm. www.HolocaustCenterSeattle.org A seven year-old Siegfried “Fred” Fedrid pictured with his mother, an aunt, and other cousins in Vienna, circa 1927. Fred was the only survivor. iegfried “Fred” Fedrid was born in April 1920 When Fred returned to Vienna to look for his friends in Vienna, Austria. Fred was born deaf to and relatives, he found no one. Further, he was told Jewish parents who were also deaf. In 1936 Fred that the Nazis had sold all of the possessions he and his Sgraduated from the School for the Deaf in Vienna. At parents had left behind. He had lost everything. 16 years old, he began an apprenticeship in a custom tailor shop. He trained there until 1938, when the Fred was hired at a Nazis forced the owner of the shop, a Jewish man, to “He wanted people to custom tailor shop, close his business. know that deaf people lived in a rented room, are capable, intelligent, and supported himself. In October of 1941, the Gestapo arrested Fred and his and able to support family.