The Cowherd's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sagar Shiv Mandir

Sagar Shiv Mandir Sagar Shiv Mandir, Mauritius. Take a look at this place in Mauritius through the eyes of tourists. View View View View View View View View. Share your visit experience about Sagar Shiv Mandir, Mauritius and rate it: Details. coordinates Sagar Shiv Mandir is on the eastern part of Mauritius. It is a place of worship for Hindus settled in Mauritius and it is also visited by tourists. The temple was constructed in 2007 and it hosts a 108 feet height bronze coloured statue of Shiva. On every maha shivratri day at least 3 lakh people throng this place to pay their respect to the temple of Lord shiva . also next to it another statue of Ma Durga is being constructed. The temple is on bank of Ganga talao, which was supposed to be the creation of Lord shiva. Sagar Shiv Mandir is a hindu temple sitting on the island of Goyave de Chine, Mauritius territory. It is a place of worship for many hindus around the world and. vics12.wix.com. album. Album Sept 2012. Sagar Shiv Mandir Mauritius added 19 new photos to the album Sept 2012. · 3 September 2012 ·. Sept 2012 - after abhishek. Sept 2012. 19 photos. Sagar Shiv Mandir Mauritius. · 24 July 2012 ·. http://youtu.be/Y9Jstt8iXFs. Sagar Shiv Mandir - 3.1. Hindu Temple on sea, Poste de Flacq, Mauritius. youtube.com. Sagar Shiv Mandir is a Hindu temple sitting on the island of Goyave de Chine, Poste de Flacq, Mauritius. Sagar Shiv Mandir is on the eastern part of Mauritius. -

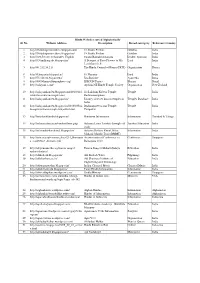

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Hindus in South Asia & the Diaspora: a Survey of Human Rights 2007

Hindus in South Asia and the Diaspora: A Survey of Human Rights 2007 www.HAFsite.org May 19, 2008 “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948, Article 1) “Religious persecution may shield itself under the guise of a mistaken and over-zealous piety” (Edmund Burke, February 17, 1788) Endorsements of the Hindu American Foundation's 3rd Annual Report “Hindus in South Asia and the Diaspora: A Survey of Human Rights 2006” I would like to commend the Hindu American Foundation for publishing this critical report, which demonstrates how much work must be done in combating human rights violations against Hindus worldwide. By bringing these abuses into the light of day, the Hindu American Foundation is leading the fight for international policies that promote tolerance and understanding of Hindu beliefs and bring an end to religious persecution. Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH) Freedom of religion and expression are two of the most fundamental human rights. As the founder and former co-chair of the Congressional Caucus on India, I commend the important work that the Hindu American Foundation does to help end the campaign of violence against Hindus in South Asia. The 2006 human rights report of the Hindu American Foundation is a valuable resource that helps to raise global awareness of these abuses while also identifying the key areas that need our attention. Congressman Frank Pallone, Jr. (D-NJ) Several years ago in testimony to Congress regarding Religious Freedom in Saudi Arabia, I called for adding Hindus, Sikhs and Buddhists to oppressed religious groups who are banned from practicing their religious and cultural rights in Saudi Arabia. -

A Survey of Human Rights 2008

HINDUS IN SOUTH ASIA AND THE DIASPORA: A Survey of Human Rights 2008 HINDU AMERICAN FOUNDATION Hindus in South Asia and the Diaspora: A Survey of Human Rights 2008 www.HAFsite.org March 13, 2009 “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948, Article 1) “Religious persecution may shield itself under the guise of a mistaken and over-zealous piety” (Edmund Burke, February 17, 1788) Endorsements of Hindu American Foundation's 4th Annual Report “Hindus in South Asia and the Diaspora: A Survey of Human Rights 2007” All of us share common values: a respect for other people, their cultures and the beliefs that they hold. But as this report demonstrates, there are still too many instances where that respect is violated and people’s rights are horribly abused. The Hindu American Foundation has done a great service by bringing these human rights abuses to light. Working together, I believe we can deliver the basic freedoms every person is due. Senator Frank Lautenberg (D-NJ) I commend the Hindu American Foundation on its report, "Hindus in South Asia and the Diaspora: A Survey of Human Rights 2007." This report importantly documents the plight of persecuted Hindus throughout South Asia. As the Ranking Member of the Subcommittee on Terrorism, I have seen how the growth of radical Islam impacts the well-being of the Hindu population. Reports like this are important in documenting these human rights abuses. Rep. Ed Royce (R-CA) As the world increasingly becomes a global village, it is important to monitor, acknowledge and work towards promoting freedom of speech and conscience for all. -

PILGRIM CENTRES of INDIA (This Is the Edited Reprint of the Vivekananda Kendra Patrika with the Same Theme Published in February 1974)

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA A DISTINCTIVE CULTURAL MAGAZINE OF INDIA (A Half-Yearly Publication) Vol.38 No.2, 76th Issue Founder-Editor : MANANEEYA EKNATHJI RANADE Editor : P.PARAMESWARAN PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA (This is the edited reprint of the Vivekananda Kendra Patrika with the same theme published in February 1974) EDITORIAL OFFICE : Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan Trust, 5, Singarachari Street, Triplicane, Chennai - 600 005. The Vivekananda Kendra Patrika is a half- Phone : (044) 28440042 E-mail : [email protected] yearly cultural magazine of Vivekananda Web : www.vkendra.org Kendra Prakashan Trust. It is an official organ SUBSCRIPTION RATES : of Vivekananda Kendra, an all-India service mission with “service to humanity” as its sole Single Copy : Rs.125/- motto. This publication is based on the same Annual : Rs.250/- non-profit spirit, and proceeds from its sales For 3 Years : Rs.600/- are wholly used towards the Kendra’s Life (10 Years) : Rs.2000/- charitable objectives. (Plus Rs.50/- for Outstation Cheques) FOREIGN SUBSCRIPTION: Annual : $60 US DOLLAR Life (10 Years) : $600 US DOLLAR VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements 1 2. Editorial 3 3. The Temple on the Rock at the Land’s End 6 4. Shore Temple at the Land’s Tip 8 5. Suchindram 11 6. Rameswaram 13 7. The Hill of the Holy Beacon 16 8. Chidambaram Compiled by B.Radhakrishna Rao 19 9. Brihadishwara Temple at Tanjore B.Radhakrishna Rao 21 10. The Sri Aurobindo Ashram at Pondicherry Prof. Manoj Das 24 11. Kaveri 30 12. Madurai-The Temple that Houses the Mother 32 13. -

Ramleela in Trinidad, 2006–2008

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Faculty Scholarship Spring 2010 Performing in the Lap and at the Feet of God: Ramleela in Trinidad, 2006–2008 Milla C. Riggio Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/facpub Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Performing in the Lap and at the Feet of God Ramleela in Trinidad, 2006–2008 Milla Cozart Riggio The performance was like a dialect, a branch of its original language, an abridgement of it, but not a distortion or even a reduction of its epic scale. Here in Trinidad I had discovered that one of the greatest epics of the world was seasonally performed, not with that desperate resignation of preserving a culture, but with an openness of belief that was as steady as the wind bending the cane lances of the Caroni plain. —Derek Walcott, Nobel Prize Lecture (1992) As a child living in Wagoner, Oklahoma, I was enlisted by my Baptist evangelist father both to play the piano for his monthly hymn singing fests and to “teach” Wednesday night Bible classes. “What,” I asked my father, “shall I tell these people? I don’t know anything about the Bible.” “Oh,” he responded, “neither do they. Just make it up, but always assure them that—as our good hymn says—they are all ‘sitting in the lap of God.’ That’s what they want to know.” So week after week, while I unwittingly practiced for my future vocation, some dozen or so Baptist parishioners were asked by a nine-year-old girl to sit together “in the lap of God.” Having no idea what that meant, I conjured up an image of a gray-bearded, department store Santa/God with all of us piling at once into his opulent lap. -

Pradipta(SEPHIS)

CONTENTS Editorial Symposia South 02 Samita Sen, Shamil Jeppie, Carlos I. Degregori 36 Chandak Sengoopta, Relocating Ray: Beyond Renoir, Renaissance and Revolution. 03 Letters Across the South Vishnu Padayachee, The Story of Ike’s Bookshop, 3 38 Interview 33 Durban, South Africa. Manujendra Kundu, Third Theatre in Bengal: An 04 Interview with Badal Sircar 39 Lakshmi Subramanian, A recent trip to Thailand. 40 Zulfah Otto-Sallies, Weaving a filmmaker’s dream. 34 Articles 42 Gairoonisa Paleker, Cinematic South: Shifting Centres, Human Rights and the Tri-Continents Film Festival. Aishika Chakraborty, Navanritya: Her Body, 07 Her Dance. 43 Angela Figueiredo, Report for the VIII Fábrica de Idéias. Gairoonisa Paleker, Film as History– Some 12 Reflections on the Student Documentary Film Cissie Gool. 44 Lara Mancuso, Trip to Mexico City. Meg Samuelson, Historical Time, Gender and 15 the ‘New’ South Africa in Zakes Mda’s The Reviews Heart of Redness. 45 Nubia Pinto, City of God: The life of black people in Brazilian slums. Contemporary South 46 Zakariyau Sadiq Sambo, Transforming the Cellu- 19 Nilosree Biswas, Where is Thelma and Louise? loid: Nollywood films and Nigerian Society. Kumar Mahabir, Temples and tourism in Trinidad 48 Cecilia Gallero, Memories of War. Iluminados Por El 21 and Tobago. Fuego / Enlighten by Fire. 23 Jishnu Dasgupta, Twists and Turns. 49 Announcements Archives and Field Notes Abanti Adhikari, Bangladesh in the eyes of an 54 Our Team 25 observer. A Photo-Essay 41 Sanchari Sur, Shameek Sarkar & Jishnu 28 Dasgupta, The Biggest Sculpture Show in the World: Durga Puja in Calcutta. Contact us at [email protected] SEPHIS e-magazine 2, 2, January 2006 02 Editorial Samita Sen Shamil Jeppie Carlos I. -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

'Even Fish Have an Ethnicity'

‘Even fish have an ethnicity’: Livelihoods and Identities of Men and Women in War-affected Coastal Trincomalee, Sri Lanka Coastal War-affected Women in ‘Even fish have an ethnicity’: Livelihoods and Identities of Men ‘Even fish have an ethnicity’: Livelihoods and Identities of Men and Women in War-affected Coastal Trincomalee, Sri Lanka Gayathri Lokuge Gayathri Lokuge ‘Even Fish Have an Ethnicity’: Livelihoods and Identities of Men and Women in War-affected Coastal Trincomalee, Sri Lanka Gayathri Hiroshani Hallinne Lokuge 1 Thesis committee Supervisor Prof. dr. ir. D.J.M. (Thea) Hilhorst Special Chair for Humanitarian Aid and Reconstruction (HAR) Wageningen University, the Netherlands Co-promotors Dr Malathi de Alwis Visiting Professor, Faculty of Graduate Studies University of Colombo, Sri Lanka Prof. dr. ir. Georg Frerks Chair of Conflict Prevention and Conflict Management Utrecht University, the Netherlands Chair of International Security Studies Netherlands Defence Academy Other members Prof. dr. S.R. (Simon) Bush (Wageningen University, the Netherlands) Prof. dr. Jonathan Goodhand (School of Oriental and African Studies [SOAS], University of London, United Kingdom) Dhr. dr. J.M. (Maarten) Bavinck (Amsterdam University, the Netherlands) Dr. Shyamika Jayasundara-Smits (International Institute of Social Science, Erasmus University, the Netherlands) This research was conducted under the auspices of the Graduate School of Social Sciences. 2 ‘Even Fish Have an Ethnicity’: Livelihoods and Identities of Men and Women in War-affected Coastal Trincomalee, Sri Lanka Gayathri Hiroshani Hallinne Lokuge Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr A. P. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

'Even Fish Have an Ethnicity': Livelihoods and Identities of Men and Women in War-Affected Coastal Trincomalee, Sri Lanka

‘Even Fish Have an Ethnicity’: Livelihoods and Identities of Men and Women in War-affected Coastal Trincomalee, Sri Lanka Gayathri Hiroshani Hallinne Lokuge 1 Thesis committee Supervisor Prof. dr. ir. D.J.M. (Thea) Hilhorst Special Chair for Humanitarian Aid and Reconstruction (HAR) Wageningen University, the Netherlands Co-promotors Dr Malathi de Alwis Visiting Professor, Faculty of Graduate Studies University of Colombo, Sri Lanka Prof. dr. ir. Georg Frerks Chair of Conflict Prevention and Conflict Management Utrecht University, the Netherlands Chair of International Security Studies Netherlands Defence Academy Other members Prof. dr. S.R. (Simon) Bush (Wageningen University, the Netherlands) Prof. dr. Jonathan Goodhand (School of Oriental and African Studies [SOAS], University of London, United Kingdom) Dhr. dr. J.M. (Maarten) Bavinck (Amsterdam University, the Netherlands) Dr. Shyamika Jayasundara-Smits (International Institute of Social Science, Erasmus University, the Netherlands) This research was conducted under the auspices of the Graduate School of Social Sciences. 2 ‘Even Fish Have an Ethnicity’: Livelihoods and Identities of Men and Women in War-affected Coastal Trincomalee, Sri Lanka Gayathri Hiroshani Hallinne Lokuge Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr A. P. J. Mol in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Monday 3 July 2017 at 1.30 p.m. in the Aula 3 Gayathri Hiroshani Hallinne Lokuge ‘Even Fish Have an Ethnicity’: Livelihoods and Identities of Men and Women in War-affected Coastal Trincomalee, Sri Lanka PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, the Netherlands. -

Fairs and Festival, 4 West Godavari, Part VII

PRO. 179.4 (N) o . 7S0 .~ WEST GODAVARI CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME II ANDHRA PRADESH PART VII - B (4) FAIRS AND FESTIV (4. West Godavari District) A: CHANDRA SEKHAR OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICB Superintendent o.J,...J;_"UJIF. Q_wations, Andhra Pradesh Pnce: Rs .. 6.50 P. or 15 Sh. 2 d. or $ 2.34 c. ~9t{ CENSUS PUBLICATIONS, ANDHRA PRADESH . , ,! (All the Census Publications of this State bear Vol. No. II) PART I-A General Report PART J-B Report on Vital Statistics PART I-C Subsidiary Tables PART II-A General Population Tables PART II-B (i) Economic Tables [B-1 to B-IV] PART IJ-B (ii) Economic Tables fB-V to B-IXJ PART n-c Cultural and Migration Tables PART III .J Household Economic Tables PART IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments (with Subsidiary Tables) PART IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables PART V-A Special Tables for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART VI Village Survey MonogTaphs (46) PART VII-A (1) ~ Handicrafts Survey Reports (Selected Crafts) PART VII-A (2) PART VII-B (1 to 20), .. Fairs and Festivals (Separate Book for each District) PART VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration I ~ (Not for sale) PART VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation .J PART IX State Atlas PART X Special Report on Hyderabad City District Census Handbooks (Separate Volume for each District) ! I, f Plate I: Sri Venkateswaraswamv-Dwaraka Thirumala. Eluru Taluk - Courtesy : Commissioner. H.R.&C .E . (Admn.) Dept., A .