An Application of Mikhail Bakhtin's Theory of the Grotesque to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chaosmosis : an Ethico-Aesthetic Paradigm I Felix Guattari ; Translated by Paul Bains and Julian Pefanis

Chaosmosis an ethico-aesthetic paradigm Felix Guattari translated by Paul Bains and Julian Pefanis INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS BLOOMINGTON & INDIANAPOLIS English translation© 1995, Power Institute, Paul Bains, and Julian Pefanis Chaosmosis was originally published in French as Chaosmose. © 1992, Editions Galilee All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses' Resolutions on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39 .48-1984. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guattari, Felix. [Chaosmose. English] Chaosmosis : an ethico-aesthetic paradigm I Felix Guattari ; translated by Paul Bains and Julian Pefanis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-253-32945-0 (alk. paper). - ISBN 0-253-21004-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Psychoanalysis-Philosophy. 2. Subjectivity. I. Title. BFl 75.G81313 1995' 95-31403 194-dc20 1 2 3 4 5 00 99 98 97 96 95 On the planking, on the ship's bulwarks, on the sea, with the course of the sun through the sky and the ship, an unreadable and wrenching script takes shape, takes shape and destroys itself at the same slow pace - shadows, spines, shafts of broken light refocused in the angles, the triangles of a fleeting geometry that yields to the shadow of the ocean waves. -

Bakhtin's Theory of the Literary Chronotope: Reflections, Applications, Perspectives

literary.chronotope.book Page 3 Tuesday, May 4, 2010 5:47 PM BAKHTIN'S THEORY OF THE LITERARY CHRONOTOPE: REFLECTIONS, APPLICATIONS, PERSPECTIVES Nele Bemong, Pieter Borghart, Michel De Dobbeleer, Kristoffel Demoen, Koen De Temmerman & Bart Keunen (eds.) literary.chronotope.book Page 4 Tuesday, May 4, 2010 5:47 PM © Academia Press Eekhout 2 9000 Gent T. (+32) (0)9 233 80 88 F. (+32) (0)9 233 14 09 [email protected] www.academiapress.be The publications of Academia Press are distributed by: Belgium: J. Story-Scientia nv Wetenschappelijke Boekhandel Sint-Kwintensberg 87 B-9000 Gent T. 09 255 57 57 F. 09 233 14 09 [email protected] www.story.be The Netherlands: Ef & Ef Eind 36 NL-6017 BH Thorn T. 0475 561501 F. 0475 561660 Rest of the world: UPNE, Lebanon, New Hampshire, USA (www.upne.com) Nele Bemong, Pieter Borghart, Michel De Dobbeleer, Kristoffel Demoen, Koen De Temmerman & Bart Keunen (eds.) Bakhtin's Theory of the Literary Chronotope: Reflections, Applications, Perspectives Proceedings of the workshop entitled “Bakhtin’s Theory of the Literary Chronotope: Reflections, Applications, Perspectives” (27-28 June 2008) supported by the Royal Flemish Academy for Sciences and the Arts. Gent, Academia Press, 2010, v + 213 pp. ISBN 978 90 382 1563 1 D/2010/4804/84 U 1414 Layout: proxess.be Cover: Steebz/KHUAN No part of this publication may be reproduced in print, by photocopy, microfilm or any other means, without the prior written permission of the publisher. literary.chronotope.book Page i Tuesday, May 4, 2010 5:47 PM I CONTENTS Preface . -

Characters in Bakhtin's Theory

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 9 Issue 1 Special Issue on Mikhail Bakhtin Article 5 9-1-1984 Characters in Bakhtin's Theory Anthony Wall Queen's University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Modern Literature Commons, and the Russian Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Wall, Anthony (1984) "Characters in Bakhtin's Theory," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 9: Iss. 1, Article 5. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1151 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Characters in Bakhtin's Theory Abstract A common focus in many modern theories of literature is a reassessment of the traditional view of the character in a narrative text. The position that this article defends is that a revised conception is necessary for an understanding of the means by which dialogism is said to function in novelistic discourse. Revising the notion does not, however, involve discarding it outright as recent theories of the subject would have us do. Nor can we simply void it of all "psychological" content as suggested by many structuralist proposals. To retain Bakhtin's concept of the notion of character, we must understand the term "psychological" in the context of his early book on Freud. In artificially combining Bakhtin's isolated remarks on the literary character, we arrive at a view which postulates textualized voice-sources in the novel. -

Redalyc.GROTESQUE REALISM, SATIRE, CARNIVAL AND

Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI E-ISSN: 1576-3420 [email protected] Sociedad Española de Estudios de la Comunicación Iberoamericana España Asensio Aróstegui, Mar GROTESQUE REALISM, SATIRE, CARNIVAL AND LAUGHTER IN SNOOTY BARONET BY WYNDHAM LEWIS Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, núm. 15, marzo, 2008, pp. 95-115 Sociedad Española de Estudios de la Comunicación Iberoamericana Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=523552801005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative REVISTA DE LA SEECI. Asensio Aróstegui, Mar (2008): Grotesque realism, satire, carnival and laughter in Snooty Baronet by Wyndham Lewis. Nº 15. Marzo. Año XII. Páginas: 95-115 ISSN: 1576-3420 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2008.15.95-115 ___________________________________________________________________ GROTESQUE REALISM, SATIRE, CARNIVAL AND LAUGHTER IN SNOOTY BARONET BY WYNDHAM LEWIS REALISMO GROTESCO, LA SÁTIRA, EL CARNAVAL Y LA RISA EN SNOOTY BARONET DE WYNDHAM LEWIS AUTORA Mar Asensio Aróstegui: Profesora de la Facultad de Letras y de la Educación. Universidad de La Rioja. Logroño (España). [email protected] RESUMEN Aunque la obra del escritor británico Percy Wyndham Lewis muestra una visión satírica de la realidad, cuyas raíces se sitúan en el humor carnavalesco típico de la Edad Media y esto hace que sus novelas tengan rasgos comunes a las de otros escritores Latinoamericanos como Borges o García Márquez, la repercusión que la obra de Lewis ha tenido en los países de habla hispana es prácticamente nula. -

Dialogic Pedagogy and Semiotic-Dialogic Inquiry Into Visual Literacies and Augmented Reality

ISSN: 2325-3290 (online) Dialogic pedagogy and semiotic-dialogic inquiry into visual literacies and augmented reality Zoe Hurley Zayed University, Dubai Abstract Technological determinism has been driving conceptions of technology enhanced learning for the last two decades at least. The abrupt shift to the emergency delivery of online courses during COVID-19 has accelerated big tech’s coup d’état of higher education, perhaps irrevocably. Yet, commercial technologies are not necessarily aligned with dialogic conceptions of learning while a technological transmission model negates learners’ input and interactions. Mikhail Bakhtin viewed words as the multivocal bridge to social thought. His theory of the polysemy of language, that has subsequently been termed dialogism, has strong correlations with the semiotic philosophy of American pragmatist Charles Sanders Peirce. Peirce’s semiotic philosophy of signs extends far beyond words, speech acts, linguistics, literary genres, and/or indeed human activity. This study traces links between Bakhtin’s dialogism with Peirce’s semiotics. Conceptual synthesis develops the semiotic-dialogic framework. Taking augmented reality as a theoretical case, inquiry illustrates that while technologies are subsuming traditional pedagogies, teachers and learners, this does not necessarily open dialogic learning. This is because technologies are never dialogic, in and of themselves, although semiotic learning always involves social actors’ interpretations of signs. Crucially, semiotic-dialogism generates theorising of the visual literacies required by learners to optimise technologies for dialogic learning. Key Words: Dialogism / signs / semiotics / questioning / opening / augmented reality / technologies Zoe Hurley (PhD, Lancaster University, UK) is the Assistant Dean for Student Affairs in the College of Communication and Media Sciences at Zayed University, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. -

AN INTRODUCTION to INTERTEXTUALITY AS a LITERARY THEORY: DEFINITIONS, AXIOMS and the ORIGINATORS Mevlüde ZENGİN∗ “The Good of a Book Lies in Its Being Read

Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi Sayı 25/1, 2016, Sayfa 299-326 AN INTRODUCTION TO INTERTEXTUALITY AS A LITERARY THEORY: DEFINITIONS, AXIOMS AND THE ORIGINATORS Mevlüde ZENGİN∗ “The good of a book lies in its being read. A book is made up of signs that speak of other signs, which in their turn speak of things. Without an eye to read them, a book contains signs that produce no concepts; therefore it is dumb.” Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose Abstract The aim of this study is to provide a succinct discussion of intertextuality from a theoretical perspective. The concept of intertextuality dates back to the ancient times when the first human history and the discourses about texts began to exist. As a phenomenon it has sometimes been defined as a set of relations which a text has with other texts and/or discourses belonging to various fields and cultural domains. Yet the commencement of intertextuality as a critical theory and an approach to texts was provided by the formulations of such theorists as Ferdinand de Saussure, Mikhail Bakhtin and Roland Barthes before the term ‘intertextuality’ was coined by Julia Kristeva in 1966. This study, focusing on firstly, the path from ‘work’ to ‘text’ and ‘intertext’, both of which ultimately became synonymous, and secondly, the shifting position of the reader/interpreter becoming significant in the discipline of literary studies, aims to define intertextuality as a critical theory and state its fundamentals and axioms formulated by the mentioned originators of the intertextual theory and thus to betray the fact that intertextuality had a poststructuralist and postmodern vein at the outset. -

Dialogue in Peirce, Lotman, and Bakhtin: a Comparative Study

Dialogue in Peirce, Lotman, andSign Bakhtin: Systems AStudies comparative 44(4), 2016, study 469–493 469 Dialogue in Peirce, Lotman, and Bakhtin: A comparative study Oliver Laas School of Humanities, Tallinn University Narva mnt 25, 10120, Tallinn, Estonia/ The Chair of Graphic Art, Faculty of Fine Arts Estonian Academy of Art, Lembitu 12, 10114, Tallinn, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Th e notion of dialogue is foundational for both Juri Lotman and Mikhail Bakhtin. It is also central in Charles S. Peirce’s semeiotics and logic. While there are several scholarly comparisons of Bakhtin’s and Lotman’s dialogisms, these have yet to be compared with Peirce’s semeiotic dialogues. Th is article takes tentative steps toward a comparative study of dialogue in Peirce, Lotman, and Bakhtin. Peirce’s understanding of dialogue is explicated, and compared with both Lotman’s as well as Bakhtin’s con- ceptions. Lotman saw dialogue as the basic meaning-making mechanism in the semio sphere. Th e benefi ts and shortcomings of reconceptualizing the semiosphere on the basis of Peircean and Bakhtinian dialogues are weighed. Th e aim is to explore methodological alternatives in semiotics, not to challenge Lotman’s initial model. It is claimed that the semiosphere qua model operating with Bakhtinian dialogues is narrower in scope than Lotman’s original conception, while the semiosphere qua model operating with Peircean dialogues appears to be broader in scope. It is concluded that the choice between alternative dialogical foundations must be informed by attentiveness to their diff erences, and should be motivated by the researcher’s goals and theoretical commitments. -

The Grottesche Part 1. Fragment to Field

CHAPTER 11 The Grottesche Part 1. Fragment to Field We touched on the grottesche as a mode of aggregating decorative fragments into structures which could display the artist’s mastery of design and imagi- native invention.1 The grottesche show the far-reaching transformation which had occurred in the conception and handling of ornament, with the exaltation of antiquity and the growth of ideas of artistic style, fed by a confluence of rhe- torical and Aristotelian thought.2 They exhibit a decorative style which spreads through painted façades, church and palace decoration, frames, furnishings, intermediary spaces and areas of ‘licence’ such as gardens.3 Such proliferation shows the flexibility of candelabra, peopled acanthus or arabesque ornament, which can be readily adapted to various shapes and registers; the grottesche also illustrate the kind of ornament which flourished under printing. With their lack of narrative, end or occasion, they can be used throughout a context, and so achieve a unifying decorative mode. In this ease of application lies a reason for their prolific success as the characteristic form of Renaissance ornament, and their centrality to later historicist readings of ornament as period style. This appears in their success in Neo-Renaissance style and nineteenth century 1 The extant drawings of antique ornament by Giuliano da Sangallo, Amico Aspertini, Jacopo Ripanda, Bambaia and the artists of the Codex Escurialensis are contemporary with—or reflect—the exploration of the Domus Aurea. On the influence of the Domus Aurea in the formation of the grottesche, see Nicole Dacos, La Découverte de la Domus Aurea et la Formation des grotesques à la Renaissance (London: Warburg Institute, Leiden: Brill, 1969); idem, “Ghirlandaio et l’antique”, Bulletin de l’Institut Historique Belge de Rome 39 (1962), 419– 55; idem, Le Logge di Raffaello: Maestro e bottega di fronte all’antica (Rome: Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, 1977, 2nd ed. -

The Proliferation of the Grotesque in Four Novels of Nelson Algren

THE PROLIFERATION OF THE GROTESQUE IN FOUR NOVELS OF NELSON ALGREN by Barry Hamilton Maxwell B.A., University of Toronto, 1976 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department ot English ~- I - Barry Hamilton Maxwell 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY August 1986 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME : Barry Hamilton Maxwell DEGREE: M.A. English TITLE OF THESIS: The Pro1 iferation of the Grotesque in Four Novels of Nel son A1 gren Examining Committee: Chai rman: Dr. Chin Banerjee Dr. Jerry Zaslove Senior Supervisor - Dr. Evan Alderson External Examiner Associate Professor, Centre for the Arts Date Approved: August 6, 1986 I l~cr'ct~ygr.<~nl lu Sinnri TI-~J.;~;University tile right to lend my t Ire., i6,, pr oJcc t .or ~~ti!r\Jc~tlcr,!;;ry (Ilw tit lc! of which is shown below) to uwr '. 01 thc Simon Frasor Univer-tiity Libr-ary, and to make partial or singlc copic:; orrly for such users or. in rcsponse to a reqclest from the , l i brtlry of rllly other i111i vitl.5 i ty, Or c:! her- educational i r\.;t i tu't ion, on its own t~l1.31f or for- ono of i.ts uwr s. I furthor agroe that permissior~ for niir l tipl c copy i rig of ,111i r; wl~r'k for .;c:tr~l;rr.l y purpose; may be grdnted hy ri,cs oi tiI of i Ittuli I t ir; ~lntlc:r-(;io~dtt\at' copy in<) 01. -

The Monopteros in the Athenian Agora

THE MONOPTEROS IN THE ATHENIAN AGORA (PLATE 88) O SCAR Broneerhas a monopterosat Ancient Isthmia. So do we at the Athenian Agora.' His is middle Roman in date with few architectural remains. So is ours. He, however, has coins which depict his building and he knows, from Pau- sanias, that it was built for the hero Palaimon.2 We, unfortunately, have no such coins and are not even certain of the function of our building. We must be content merely to label it a monopteros, a term defined by Vitruvius in The Ten Books on Architecture, IV, 8, 1: Fiunt autem aedes rotundae, e quibus caliaemonopteroe sine cella columnatae constituuntur.,aliae peripteroe dicuntur. The round building at the Athenian Agora was unearthed during excavations in 1936 to the west of the northern end of the Stoa of Attalos (Fig. 1). Further excavations were carried on in the campaigns of 1951-1954. The structure has been dated to the Antonine period, mid-second century after Christ,' and was apparently built some twenty years later than the large Hadrianic Basilica which was recently found to its north.4 The lifespan of the building was comparatively short in that it was demolished either during or soon after the Herulian invasion of A.D. 267.5 1 I want to thank Professor Homer A. Thompson for his interest, suggestions and generous help in doing this study and for his permission to publish the material from the Athenian Agora which is used in this article. Anastasia N. Dinsmoor helped greatly in correcting the manuscript and in the library work. -

The Grotesque in El Greco

Konstvetenskapliga institutionen THE GROTESQUE IN EL GRECO BETWEEN FORM - BEYOND LANGUAGE - BESIDE THE SUBLIME © Författare: Lena Beckman Påbyggnadskurs (C) i konstvetenskap Höstterminen 2019 Handledare: Johan Eriksson ABSTRACT Institution/Ämne Uppsala Universitet. Konstvetenskapliga institutionen, Konstvetenskap Författare Lena Beckman Titel och Undertitel THE GROTESQUE IN EL GRECO -BETWEEN FORM - BEYOND LANGUAGE - BESIDE THE SUBLIME Engelsk titel THE GROTESQUE IN EL GRECO -BETWEEN FORM - BEYOND LANGUAGE - BESIDE THE SUBLIME Handledare Johan Eriksson Ventileringstermin: Hösttermin (år) Vårtermin (år) Sommartermin (år) 2019 2019 Content: This study attempts to investigate the grotesque in four paintings of the artist Domenikos Theotokopoulos or El Greco as he is most commonly called. The concept of the grotesque originated from the finding of Domus Aurea in the 1480s. These grottoes had once been part of Nero’s palace, and the images and paintings that were found on its walls were to result in a break with the formal and naturalistic ideals of the Quattrocento and the mid-renaissance. By the end of the Cinquecento, artists were working in the mannerist style that had developed from these new ideas of innovativeness, where excess and artificiality were praised, and artists like El Greco worked from the standpoint of creating art that were more perfect than perfect. The grotesque became an end to reach this goal. While Mannerism is a style, the grotesque is rather an effect of the ‘fantastic’.By searching for common denominators from earlier and contemporary studies of the grotesque, and by investigating the grotesque origin and its development through history, I have summarized the grotesque concept into three categories: between form, beyond language and beside the sublime. -

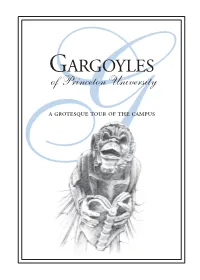

Gargoyles of Princeton University Ga Grotesque Tour of the Campus

GARGOYLES of Princeton University Ga grotesque tour of the campus 1 2 Here we were taught by men and Gothic towers democracy and faith and righteousness and love of unseen things that do not die. H. E. Mierow ’14 or centuries scholars have asked why gargoyles inhabit their most solemn churches and institutions. Fantastic explanations have come downF from the Middle Ages. Some art historians believe that gargoyles were meant to depict evil spirits over which the Christian church had triumphed. One theory suggests that these devils were frozen in stone as they fled the church. Supposedly, Christ set these spirits to work as useful examples to men instead of sending them straight to damnation. Others say they kept evil spirits away. Psychologists suggest that gargoyles represent the fears and superstitions of medieval men. As life became more secure, the gargoyles became more comical and whimsical. This little book introduces you to some men, women, and beasts you may have passed a hundred times on the campus but never noticed. It invites you to visit some old favorites. A pair of binoculars will bring you face-to-face with second- and third- story personalities. Why does Princeton have gargoyles and grotesques? Here is one excuse: … If the most fanciful and wildest sculptures were placed on the Gothic cathedrals, should they be out of place on the walls of a secular educational establishment? (“Princeton’s Gargoyles,” New York Sun, May 13, 1927) Note: Taking some technical license, the creatures and carvings described in this publication are referred to as “gargoyles” and “grotesques.” Typically, gargoyles are defined as such only when they also serve to convey water away from a building.