The Values of Ordination: the Bhikkhuni, Gender, and Thai Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination

Journal of Buddhist Ethics ISSN 1076-9005 http://blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/ Volume 22, 2015 The Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination Bhikkhu Anālayo University of Hamburg Copyright Notice: Digital copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no change is made and no alteration is made to the content. Reproduction in any other format, with the exception of a single copy for private study, requires the written permission of the author. All en- quiries to: [email protected]. The Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination Bhikkhu Anālayo1 Abstract With this paper I examine the narrative that in the Cullavagga of the Theravāda Vinaya forms the background to the different rules on bhikkhunī ordination, alternating between translations of the respective portions from the original Pāli and discussions of their implications. An appendix to the paper briefly discusses the term paṇḍaka. Introduction In what follows I continue exploring the legal situation of bhikkhunī or- dination, a topic already broached in two previous publications. In “The Legality of Bhikkhunī Ordination” I concentrated in particular on the legal dimension of the ordinations carried out in Bodhgayā in 1998.2 Based on an appreciation of basic Theravāda legal principles, I discussed the nature of the garudhammas and the need for a probationary training 1 Numata Center for Buddhist Studies, University of Hamburg, and Dharma Drum Insti- tute of Liberal Arts, Taiwan. I am indebted to bhikkhu Ariyadhammika, bhikkhu Bodhi, bhikkhu Brahmāli, bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā, and Petra Kieffer-Pülz for commenting on a draft version of this article. 2 Anālayo (“The Legality”). Anālayo, The Cullavagga on Bhikkhunī Ordination 402 as a sikkhamānā, showing that this is preferable but not indispensable for a successful bhikkhunī ordination. -

Book (2) (All) Guide to Life Maýgalà Literature Class Second and Third Grade Maýgalà Examination

Guide to life: Maýgala Literature Class Second and Third Grade Maýgala Examination CONTENTS 1. Author’s preface ------------------------------------------------- 2 2. Maýgalà is the guide of life ------------------------------------ 4 3. Maýgalà in Pàli and poetry -------------------------------------- 6 4. Maýgalà examples for second and third level--------------- 8 5. The nature and guideline of 38 Maýgalas ----------------- 26 6. Primary Mangala model essays ------------------------------- 36 7. Model essays for middle and higher forms --------------- 37 8. Extracts from "Introduction To Maýgalà" ------------------- 43 9. Selections of 38 Maýgalas explanations ---------------------- 47 10. Serial numbers of the Maýgalà ------------------------------ 109 11. Analysis of Maýgalà -------------------------------------------- 110 12. The presented text method of examination of Maýgala ---- 114 13. Old questions for second grade examination --------------- 131 14. Old third grade questions ------------------------------------ 136 15. Answers to the second grade old questions -------------- 141 16. Third great old questions and answers --------------------- 152 17. The lllustrated history of Buddha --------------------------- 206 18. Proverbs to write essays ------------------------------------- 231 19. Great abilities of Maýgalà ------------------------------------ 234 Book (2) (all) Guide To Life Maýgalà literature class Second and Third Grade Maýgalà Examination Written by Lay-Ein-Su Ashin Vicittasàra Translated by U Han Htay, B.A Advisor, -

BUDDHA SRAVAKA DHARMAPITHAYA [Cap.386

BUDDHA SRAVAKA DHARMAPITHAYA [Cap.386 CHAPTER 386 BUDDHA SRAVAKA DHARMAPITHAYA Act AN ACT TO MAKE PROVISION FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT AND REGULATION OF No, 16 of 1968. A UNIVERSITY FOR BHIKKHUS. [31st May, 1968.] Short title. 1. This Act may be cited as the Buddha (d) to sell, hypothecate, lease, exchange Sravaka Dharmapithaya Act. or otherwise dispose of any such property; and PART I (e) to exercise and perform in accordance with the provisions of this Act and of the Statutes and THE BUDDHA SRAVAKA Rules, whenever necessary, all the DHARMAPITHAYA powers and duties conferred or imposed on the University by any of such provisions: Establishment 2. (1) There shall be established a and unitary and residential University for incorporation bhikkhus. The University*, so established, Provided that any sale, hypothecation, of Buddha lease, exchange or other disposition of any Sravaka shall have the name and style of "The such property shall be void if it is made in Dharma- Buddha Sravaka Dharmapithaya ". pithaya. contravention of any restriction, condition or prohibition imposed by law or by the (2) The University shall have its seat on instrument by which the property was such site as the Minister may determine by vested in the University. Order published in the Gazette. 3. The objects of the University shall Objects of the be_ University. (3) The Dharmapithadhipati and the members for the time being of the (a) to train bhikkhus in accordance with Anusasaka Mandalaya, the Board of the teachings of the Buddha; Education and Administration and the Dayaka Mandalaya shall be a body (b) to promote meditation among the corporate with perpetual succession and students of the University ; with the same name as that assigned to the (c) to train bhikkhus for the University by subsection (1), and shall have propagation of the teachings of the power in such name— Buddha in Sri Lanka and abroad; to sue and be sued in all courts; (d) to encourage the study of, and (a) research in. -

Buddhism Illuminated: Manuscript Art from Southeast Asia London: the British Library, 2018

doi: 10.14456/jms.2018.27 ISBN 978 0 7123 5206 2. Book Review: San San May and Jana Igunma. Buddhism Illuminated: Manuscript Art from Southeast Asia London: The British Library, 2018. 272 pages. Bonnie Pacala Brereton Email: [email protected] This stunning book is superb in every way. Immediately obvious is the quality of the photographs of the British Library’s extensive collections; equally remarkable is the amount of information about the objects in the collections and how they relate to local histories, teachings, sacred sites and legends. Then there is the writing — clear and succinct, free from academic jargon and egoistic agendas. The authors state in the preface that through this book they wished to honor Dr. Henry Ginsburg, who worked for the British Library for 30 years, building up one of the finest collections of Thai illustrated manuscripts in the world before his untimely death in 2007. Dr. Ginsburg would surely be delighted at this magnificent way of paying tribute. The authors, San San May and Jana Ignunma, hold curatorial positions at the British Library, and thus are in close contact with the material they write about. In organizing a book that aims to highlight items in a museum’s or library’s collection, authors are faced with many choices. Should it be organized by date, theme, medium, provenance etc.? Here they have chosen to examine the items in terms of their relationship to the essential aspects of Theravada Buddhism as practiced in mainland Southeast Asia: the components of the Three Gems (the Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha) and the concepts of Kamma (cause and effect) and Punna (merit). -

Samanera-Course-1.Pdf

Pa-Auk Meditation Centre: Sāmaṇera Course, Lesson 1 Why Ordain? Raṭṭhapāla Sutta • King’s understanding of one’s reasons for ordaining; the 4 kinds of loss: o Loss through ageing o Loss through sickness o Loss of wealth o Loss of relatives • Bhante Raṭṭhapāla’s answer o Life in any world is unstable, it is swept away. o Life in any world has no shelter and no protector. o Life in any world has nothing of its own; one has to leave all and pass on. o Life in any world is incomplete, insatiate, the slave of craving. The Age of a Bhikkhu During the early days of Buddha’s time, all were ordained as Bhikkhu. Later on, the Buddha laid down the rule that before the age of 20, one cannot ordain as a Bhikkhu. Thus, the Sāmaṇera group begins to have a clearer role in the Buddhist hierarchy of training. There is a story behind this rule. The Buddha was staying in Rājagaha. A group of 17 children who were friends had among them Upāli as the leader. Upāli’s parents thought: What kind of livelihood will our Upāli be able to undertake with happiness after we pass on? At first, they thought that it would be beneficial for Upāli to learn writing. Later on, they thought: “If our son writes as a career, his fingers will be tired and he will suffer. It would be beneficial for Upāli to learn mathematics.” Later on, they thought: “If our son learns mathematics, his chest (heart) will be tired and he will suffer. -

Chan in Communist China: Justifying Buddhism's Turn to Practical Labor Under the Chinese Communist Party

Constructing the Past Volume 15 Issue 1 Article 9 5-30-2014 Chan in Communist China: Justifying Buddhism's Turn to Practical Labor Under the Chinese Communist Party Kenneth J. Tymick Illinois Wesleyan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing Recommended Citation Tymick, Kenneth J. (2014) "Chan in Communist China: Justifying Buddhism's Turn to Practical Labor Under the Chinese Communist Party," Constructing the Past: Vol. 15 : Iss. 1 , Article 9. Available at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing/vol15/iss1/9 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by editorial board of the Undergraduate Economic Review and the Economics Department at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Chan in Communist China: Justifying Buddhism's Turn to Practical Labor Under the Chinese Communist Party Abstract A prominent Buddhist reformer, Ju Zan, and twenty-one other progressive monks sent a letter to Mao Zedong appealing to the congenial nature between the two parties at the dawn of the Communist takeover in China. -

Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements

Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Alan Robert Lopez Chiang Mai , Thailand ISBN 978-1-137-54349-3 ISBN 978-1-137-54086-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-54086-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956808 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Cover image © Nickolay Khoroshkov / Alamy Stock Photo Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Nature America Inc. -

Gerontocracy of the Buddhist Monastic Administration in Thailand

Simulacra | ISSN: 2622-6952 (Print), 2656-8721 (Online) https://journal.trunojoyo.ac.id/simulacra Volume 4, Issue 1, June 2021 Page 43–56 Gerontocracy of the Buddhist monastic administration in Thailand Jesada Buaban1* 1 Indonesian Consortium for Religious Studies, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia * Corresponding author E-mail address: [email protected] DOI: https://doi.org/10.21107/sml.v4i1.9880 Article Info Abstract Keywords: This paper examines the monastic administration in Thai Buddhism, dhamma studies which is ruled by the senior monks and supported by the government. It aims to answer two questions; (1) why the Sangha’s administration has gerontocracy been designed to serve the bureaucratic system that monks abandon social Sangha Council and political justices, and (2) how the monastic education curriculum are secularism designed to support such a conservative system. Ethnographic methodology Thai Buddhism was conducted and collected data were analyzed through the concept of gerontocracy. It found that (1) Thai Buddhism gains supports from the government much more than other religions. Parallel with the state’s bureaucratic system, the hierarchical conservative council contains the elderly monks. Those committee members choose to respond to the government policy in order to maintain supports rather than to raise social issues; (2) gerontocracy is also facilitated by the idea of Theravada itself. In both theory and practice, the charismatic leader should be the old one, implying the condition of being less sexual feeling, hatred, and ignorance. Based on this criterion, the moral leader is more desirable than the intelligent. The concept of “merits from previous lives” is reinterpreted and reproduced to pave the way for the non-democratic system. -

Discourses of Ethno-Nationalism and Religious Fundamentalism

DISCOURSES OF ETHNO-NATIONALISM AND RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM SRI LANKAN DISCOURSES OF ETHNO-NATIONALISM AND RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM By MYRA SIVALOGANATHAN, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Myra Sivaloganathan, June 2017 M.A. Thesis – Myra Sivaloganathan; McMaster University – Religious Studies. McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2017) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: Sri Lankan Discourses of Ethno-Nationalism and Religious Fundamentalism AUTHOR: Myra Sivaloganathan, B.A. (McGill University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Mark Rowe NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 91 ii M.A. Thesis – Myra Sivaloganathan; McMaster University – Religious Studies. Abstract In this thesis, I argue that discourses of victimhood, victory, and xenophobia underpin both Sinhalese and Tamil nationalist and religious fundamentalist movements. Ethnic discourse has allowed citizens to affirm collective ideals in the face of disparate experiences, reclaim power and autonomy in contexts of fundamental instability, but has also deepened ethnic divides in the post-war era. In the first chapter, I argue that mutually exclusive narratives of victimhood lie at the root of ethnic solitudes, and provide barriers to mechanisms of transitional justice and memorialization. The second chapter includes an analysis of the politicization of mythic figures and events from the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahāvaṃsa in nationalist discourses of victory, supremacy, and legacy. Finally, in the third chapter, I explore the Liberation Tiger of Tamil Eelam’s (LTTE) rhetoric and symbolism, and contend that a xenophobic discourse of terrorism has been imposed and transferred from Tamil to Muslim minorities. Ultimately, these discourses prevent Sri Lankans from embracing a multi-ethnic and multi- religious nationality, and hinder efforts at transitional justice. -

Maha Oya Road. 25 Kms SW of Batticaloa

31 Piyangala AS. Rājagalatenna 32068. Near Mayadunna, near Bakiella. North of Uhana, midway along the Amapara - Maha Oya road. 25 kms SW of Batticaloa. Large forest area (1 square mile) bordering a wildlife sanctuary and the extensive ancient Rājagala monastery ruins situated on top of the mountain. Some caves. There is an army camp near the place due to its proximity to LTTE areas. Two monks. The place is supposed to be quite nice. Affiliated to Galdūwa. Veheragala A. Maha Oya. Midway on the Mahiyangana -Batticaloa Road. Ancient cave monastery on a hill 1 km from the Maha Oya hot springs. This used to be an arañña built by Ven. Ambalampitiya Rāhula (the founder of Bowalawatta A.), but it was abandoned after a hurricane destroyed the buildings 15 or so years ago. No monks at present, but there are 4 caves kuñis which are inhabitable and can be repaired. Supposed to be a nice place. Jaffna District. Dambakolapatuna. Keerimalai, Kankasanture. One or two kuñis in quiet dune area near the beach, close to the Navy base to which the kuñi is connected. It is possible to go on piõóapāta in nearby villages. This is supposedly the place where the Sri Mahā Bodhi arrived in Sri Lanka. 30 Mahasudharshana AS. Gadugodawāwa, Pahala-oya-gama, Ūraniya. (Between Mahiyangana and Bibile). Affiliated to Waturawila. Polonaruwa District. The second ancient capital of Sri Lanka. There are quite a few ancient monasteries on the hills and rocks in this area. Hot climate with dry season. Low country with some hills and rock-outcrops. Some large national parks. -

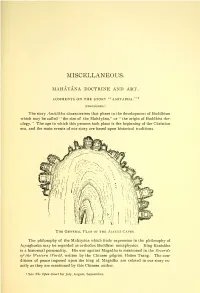

The Mahayana Doctrine and Art. Comments on the Story of Amitabha

MISCEIvIvANEOUS. MAHAYANA DOCTRINE AND ART. COMMENTS ON THE STORY "AMITABHA."^ (concluded.) The story Amitabha characterises that phase in the development of Buddhism which may be called " the rise of the Mahayana," or " the origin of Buddhist the- ology." The age in which this process took place is the beginning of the Christian era, and the main events of our story are based upon historical traditions. The General Plan of the Ajant.v Caves. The philosophy of the Mahayana which finds expression in the philosophy of Acvaghosha may be regarded as orthodox Buddhist metaphysics. King Kanishka is a historical personality. His war against Magadha is mentioned in the Records of the Western IVorld, written by the Chinese pilgrim Hsiien Tsang. The con- ditions of peace imposed upon the king of Magadha are related in our story ex- actly as they are mentioned by this Chinese author. 1 See The Open Court for July, August, September. 622 THE OPEN COURT. The monastic life described in the first, second, and fifth chapters of the story Amitdbha is a faithful portrayal of the historical conditions of the age. The ad- mission and ordination of monks (in Pali called Pabbajja and Upasampada) and the confession ceremony (in Pfili called Uposatha) are based upon accounts of the MahSvagga, the former in the first, the latter in the second, Khandaka (cf. Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XIII.). A Mother Leading Her Child to Buddha. (Ajanta caves.) Kevaddha's humorous story of Brahma (as told in The Open Cozirt, No. 554. pp. 423-427) is an abbreviated account of an ancient Pali text. -

Bridging Worlds: Buddhist Women's Voices Across Generations

BRIDGING WORLDS Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo First Edition: Yuan Chuan Press 2004 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2018 Copyright © 2018 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover Illustration, "Woman on Bridge" © 1982 Shig Hiu Wan. All rights reserved. "Buddha" calligraphy ©1978 Il Ta Sunim. All rights reserved. Chapter Illustrations © 2012 Dr. Helen H. Hu. All rights reserved. Book design and layout by Lillian Barnes Bridging Worlds Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo 7th Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women With a Message from His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I iv | Bridging Worlds Contents | v CONTENTS MESSAGE His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii INTRODUCTION 1 Karma Lekshe Tsomo UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN AROUND THE WORLD Thus Have I Heard: The Emerging Female Voice in Buddhism Tenzin Palmo 21 Sakyadhita: Empowering the Daughters of the Buddha Thea Mohr 27 Buddhist Women of Bhutan Tenzin Dadon (Sonam Wangmo) 43 Buddhist Laywomen of Nepal Nivedita Kumari Mishra 45 Himalayan Buddhist Nuns Pacha Lobzang Chhodon 59 Great Women Practitioners of Buddhadharma: Inspiration in Modern Times Sherab Sangmo 63 Buddhist Nuns of Vietnam Thich Nu Dien Van Hue 67 A Survey of the Bhikkhunī Saṅgha in Vietnam Thich Nu Dong Anh (Nguyen Thi Kim Loan) 71 Nuns of the Mendicant Tradition in Vietnam Thich Nu Tri Lien (Nguyen Thi Tuyet) 77 vi | Bridging Worlds UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN OF TAIWAN Buddhist Women in Taiwan Chuandao Shih 85 A Perspective on Buddhist Women in Taiwan Yikong Shi 91 The Inspiration ofVen.