WRAP THESIS Tsang 2015.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T and Analysis of Walkability in Hong Kong

Measurement and Analysis of Walkability in Hong Kong By: Michael Audi, Kathryn Byorkman, Alison Couture, Suzanne Najem ZRH006 Measurement and Analysis of Walkability in Hong Kong An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the faculty of the Worcester Polytechnic Institute In partial fulfillment of the requirements for Degree of Bachelor of Science In cooperation with Designing Kong Hong, Ltd. and The Harbour Business Forum On March 4, 2010 Submitted by: Submitted to: Michael Audi Paul Zimmerman Kathryn Byorkman Margaret Brooke Alison Couture Dr. Sujata Govada Suzanne Najem Roger Nissim Professor Robert Kinicki Professor Zhikun Hou ii | P a g e Abstract Though Hong Kong’s Victoria Harbour is world-renowned, the harbor front districts are far from walkable. The WPI team surveyed 16 waterfront districts, four in-depth, assessing their walkability using a tool created by the research team and conducted preference surveys to understand the perceptions of Hong Kong pedestrians. Because pedestrians value the shortest, safest, least-crowded, and easiest to navigate routes, this study found that confusing routes, unsafe or indirect connections, and a lack of amenities detract from the walkability in Hong Kong. This report provides new data concerning the walkability in harbor front districts and a tool to measure it, along with recommendations for potential improvements. iii | P a g e Acknowledgements Our team would like to thank the many people that helped us over the course of this project. First, we would like to thank our sponsors Paul Zimmerman, Dr. Sujata Govada, Margaret Brooke, and Roger Nissim for their help and dedication throughout our project and for providing all of the resources and contacts that we required. -

Past Awardees of Hong Kong Outstanding Students Award

Past Awardees of Hong Kong Outstanding Students Award English Name School Name Award No. 25th (2009-2010) CHAN, O-yinn Wharton German Swiss International School Winner 2405 KWOK, Chit Pan Ivan Queen's College Winner 2415 CHENG, Wing Yee Stephaine St. Paul's Convent School Winner 2507 CHEUNG, Yan Yee Christie St. Mary's Canossian College Winner 2508 CHIU, Yuen Ying Zelda Madam Lau Kam Lung Secondary School of MBFM Winner 2510 LUK, Man Ping Maggie Sha Tin Government Secondary School Winner 2525 NG, Yin Ki Pui Ching Middle School Winner 2528 SO, Yik Ka Diocesan Girls' School Winner 2531 TAI, Timothy St. Joseph's College Winner 2533 WAN, Fong Ying NTHYK Yuen Long District Secondary School Winner 2534 AU, Wai Man Candice SKH Bishop Mok Sau Tseng Secondary School Finalist 2501 AU YEUNG, So Hung Christian & Missionary Alliance Sun Kei Secondary School Finalist 2502 CHAN, King Yan Kristine Maryknoll Convent School (Secondary Section) Finalist 2503 CHAN, Man Hin Keith German Swiss International School Finalist 2504 CHAN, Tsz Kwan Amy Queen Elizabeth School Finalist 2505 CHENG, Ho Fung Griffith La Salle College Finalist 2506 CHEUNG, Yee Ching Gabriel Tsuen Wan Government Secondary School Finalist 2509 FUNG, Hei Wai Michelle St. Stephan's Girls' College Finalist 2511 KWONG, Ho Chak Robert Christian Alliance SC Chan Memorial College Finalist 2512 LAI, Hei Tung Theodora St. Paul's Convent School Finalist 2513 LAI, Ho Chun Samuel Tsuen Wan Government Secondary School Finalist 2514 LAI, Tsz Ting Mabel St. Paul's School (Lam Tin) Finalist 2515 LAM, Jun Hay Nicholas Diocesan Boys' School Finalist 2516 LAU, Chun Kit David HKMLC Queen Maud Secondary School Finalist 2517 LEE, Ka Ki Pinky PLK Tang Yuk Tien College Finalist 2518 LEI, Ming Wai Our Lady of the Rosary College Finalist 2519 Copyright@2020 Youth Arch Foundation English Name School Name Award No. -

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information: Capital Population (million) 7.474n/a Total Area 1,104 km² Currency 1 CAN$=5.791 Hong Kong $ (HKD) (2020 - Annual average) National Holiday Establishment Day, 1 July 1997 Language(s) Cantonese, English, increasing use of Mandarin Political Information: Type of State Type of Government Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Bilateral Product trade Canada - Hong Kong 5000 4500 4000 Balance 3500 3000 Can. Head of State Head of Government Exports 2500 President Chief Executive 2000 Can. Imports XI Jinping Carrie Lam Millions 1500 Total 1000 Trade 500 Ministers: Chief Secretary for Admin.: Matthew Cheung 0 Secretary for Finance: Paul CHAN 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Statistics Canada Secretary for Justice: Teresa CHENG Main Political Parties Canadian Imports Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), Democratic Party from: Hong Kong (DP), Liberal Party (LP), Civic Party, League of Social Democrats (LSD), Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood (HKADPL), Hong Kong Federation of Precio us M etals/ stones Trade Unions (HKFTU), Business and Professionals Alliance for Hong Kong (BPA), Labour M ach. M ech. Elec. Party, People Power, New People’s Party, The Professional Commons, Neighbourhood and Prod. Worker’s Service Centre, Neo Democrats, New Century Forum (NCF), The Federation of Textiles Prod. Hong Kong and Kowloon Labour Unions, Civic Passion, Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union, HK First, New Territories Heung Yee Kuk, Federation of Public Housing Estates, Specialized Inst. Concern Group for Tseung Kwan O People's Livelihood, Democratic Alliance, Kowloon East Food Prod. -

Annex List of Development Bureau's Initiatives in the Policy Address

Annex List of Development Bureau’s Initiatives in the Policy Address Supplement A list of Development Bureau’s initiatives, progress made on completed initiatives or those that have attained major progress and challenge ahead stipulated in the Policy Address Supplement is appended below. They are mainly under the Chapters of “Good Governance”, “Housing and Land Supply”, “Diversified Economy” and “Liveable City”. Good Governance Progress Made The Judiciary has established a central steering committee to oversee the implementation of the new High Court and District Court projects. The statutory rezoning procedures for the latter’s development site commenced in May 2019. Housing and Land Supply New Initiatives Expedite land use reviews for brownfield sites with higher development potential and certain squatter areas in urban districts, with a view to boosting land supply for public housing development. Announce a proposed framework for the Land Sharing Pilot Scheme and start accepting applications in early 2020. Amend the Outline Zoning Plans to incorporate the recommendations of the planning and engineering feasibility studies on the two action areas in Kwun Tong and Kowloon Bay, commence demolition of the former Kowloon Bay Waste Recycling Centre to release the land for commercial development, and undertake engineering investigation and design for the infrastructural facilities in Kwun Tong Action Area, with a view to further promoting the transformation of Kowloon East into the second core business district. Review the development potential of over 300 sites originally ‐ 2 ‐ earmarked for standalone “Government, Institution or Community” (GIC) facilities, with a view to optimising land use and expediting development. Progress Made The URA has identified two clusters of sites involving more than 30 Civil Servants’ Co-operative Building Society Scheme buildings in Kowloon City for re-development as a pilot project. -

T It W1~~;T~Ril~T,~

University of Hong Kong Libraries Publications, No.7 LIBRARIES AND INFORMATION CENTRES IN HONG KONG t it W1~~;t~RIl~t,~ Compiled and edited by Julia L.Y. Chan ~B~ B.A., M.L.S., A.H.I.P., FHKLA Angela S.W. Van I[I~Uw~ B.A., M.L.S., A.H.I.P., A.A.L.I.A. Kan Lai-bing MBiJl( B.Sc., M.A., M.L.S., Ph.D., Hon. D.Litt, A.L.A.A., M.I.Inf. Sc., FHKLA Published for The Hong Kong Library Association by Hong Kong University Press * 1~ *- If ~ )i[ ltd: Hong Kong University Press 139 Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong © Hong Kong University Press 1996 ISBN 962 209 409 0 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in Hong Kong by United League Graphic & Printing Company Limited Contents Plates Preface xv Introduction xvii Abbreviations & Acronyms xix Alphabetical Directory xxi Organization Listings, by Library Types 533 Libraries Open to the Public 535 Post-Secondary College and University Libraries 538 School Libraries 539 Government Departmental Libraries 550 HospitallMedicallNursing Libraries 551 Special Libraries 551 Club/Society Libraries 554 List of Plates University of Hong Kong Main Library wnt**II:;:tFL~@~g University of Hong Kong Main Library - Electronic Infonnation Centre wnt**II:;:ffr~+~~n9=t{., University of Hong Kong Libraries - Chinese Rare Book Room wnt**II:;:i139=t)(~:zjs:.~ University of Hong Kong Libraries - Education -

Hong Kong's Pro-Democracy Protests

Protests & Democracy: Hong Kong’s Pro-Democracy Protests Jennifer Yi Advisor: Professor Tsung Chi Politics Senior Comprehensive Project Candidate for Honors consideration April 10, 2015 2 Abstract Protests that occur in the public sphere shed light on the different types of democracy that exist in a region. A protester’s reason for participation demonstrates what type of democracy is missing, while a protest itself demonstrates what type of democracy exists in the region. This Politics Senior Comprehensive Project hypothesizes that the recent pro-democracy protests in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (“Hong Kong”), dubbed the Umbrella Movement, demonstrate an effective democracy due to active citizen engagement within the public sphere. Data is collected through personal interviews of Umbrella Movement participants that demonstrate what type of democracy currently exists in Hong Kong, what type of democracy protesters are looking for, and what type of democracy exists as a result of the recent protests. The interviews show that a true representative and substantive democracy do not exist in Hong Kong as citizens are not provided the democratic rights that define these types of democracy. However, the Umbrella Movement demonstrates an effective democracy in the region as citizens actively engage with one another within the public sphere for the purpose of achieving a representative and substantive democracy in Hong Kong. 3 I. Introduction After spending most of my junior year studying in Hong Kong, I have become very interested in the region and its politics. I am specifically interested in the different types of democracy that exist in Hong Kong as it is a special administrative region of the People’s Republic of China (“China”). -

Branch List English

Telephone Name of Branch Address Fax No. No. Central District Branch 2A Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2160 8888 2545 0950 Des Voeux Road West Branch 111-119 Des Voeux Road West, Hong Kong 2546 1134 2549 5068 Shek Tong Tsui Branch 534 Queen's Road West, Shek Tong Tsui, Hong Kong 2819 7277 2855 0240 Happy Valley Branch 11 King Kwong Street, Happy Valley, Hong Kong 2838 6668 2573 3662 Connaught Road Central Branch 13-14 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2841 0410 2525 8756 409 Hennessy Road Branch 409-415 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2835 6118 2591 6168 Sheung Wan Branch 252 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2541 1601 2545 4896 Wan Chai (China Overseas Building) Branch 139 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2529 0866 2866 1550 Johnston Road Branch 152-158 Johnston Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2574 8257 2838 4039 Gilman Street Branch 136 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2135 1123 2544 8013 Wyndham Street Branch 1-3 Wyndham Street, Central, Hong Kong 2843 2888 2521 1339 Queen’s Road Central Branch 81-83 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong 2588 1288 2598 1081 First Street Branch 55A First Street, Sai Ying Pun, Hong Kong 2517 3399 2517 3366 United Centre Branch Shop 1021, United Centre, 95 Queensway, Hong Kong 2861 1889 2861 0828 Shun Tak Centre Branch Shop 225, 2/F, Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2291 6081 2291 6306 Causeway Bay Branch 18 Percival Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 2572 4273 2573 1233 Bank of China Tower Branch 1 Garden Road, Hong Kong 2826 6888 2804 6370 Harbour Road Branch Shop 4, G/F, Causeway Centre, -

Public Order Policing in Hong Kong the Mongkok Riot Kam C

PUBLIC ORDER POLICING IN HONG KONG THE MONGKOK RIOT KAM C. WONG Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia Series Editors Bill Hebenton Criminology & Criminal Justice University of Manchester Manchester, UK Susyan Jou School of Criminology National Taipei University Taipei, Taiwan Lennon Y. C. Chang School of Social Sciences Monash University Melbourne, VIC, Australia This bold and innovative series provides a much needed intellectual space for global scholars to showcase criminological scholarship in and on Asia. Reflecting upon the broad variety of methodological traditions in Asia, the series aims to create a greater multi-directional, cross-national under- standing between Eastern and Western scholars and enhance the field of comparative criminology. The series welcomes contributions across all aspects of criminology and criminal justice as well as interdisciplinary studies in sociology, law, crime science and psychology, which cover the wider Asia region including China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Korea, Macao, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14719 Kam C. Wong Public Order Policing in Hong Kong The Mongkok Riot Kam C. Wong Xavier University (Emeritus) Cincinnati, OH, USA Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia ISBN 978-3-319-98671-5 ISBN 978-3-319-98672-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98672-2 Library of Congress Control -

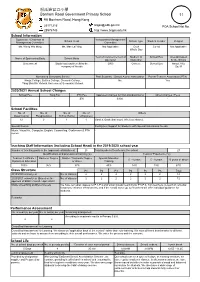

SAP Crystal Reports

般咸道官立小學 Bonham Road Government Primary School 11 9A Bonham Road, Hong Kong 25171216 [email protected] POA School Net No. 28576743 http://www.brgps.edu.hk School Information Supervisor / Chairman of Incorporated Management School Head School Type Student Gender Religion Management Committee Committee Ms. Wong Wai Ming Ms. Man Lai Ying Not Applicable Gov't Co-ed Not Applicable Whole Day Year of Commencement of Medium of School Bus Area Occupied Name of Sponsoring Body School Motto Operation Instruction by the School Government Study hard and benefit by the 2000 Chinese School Bus About 3765 company of friends Sq. M Nominated Secondary School Past Students' / School Alumni Association Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) King's College, Belilios College, Clementi College, No Yes Tang Shiu Kin Victoria Government Secondary School 2020/2021 Annual School Charges School Fee Tong Fai PTA Fee Approved Charges for Non-standard Items Other Charges / Fees - - $70 $300 - School Facilities No. of No. of No. of No. of Others Classroom(s) Playground(s) School Hall(s) Library(ies) 12 2 1 1 Garden, Basketball court, Wireless intranet. Special Rooms Facility(ies) Support for Students with Special Educational Needs Music, Visual Art, Computer, English, Counselling, Conference & PTA - rooms. Teaching Staff Information (including School Head) in the 2019/2020 school year Number of teaching posts in the approved establishment 25 Total number of teachers in the school 27 Qualifications and professional training (%) Years of Experience (%) Teacher Certificate / Bachelor Degree Master / Doctorate Degree Special Education 0 - 4 years 5 - 9 years 10 years or above Diploma in Education or above Training 100% 96% 33% 40% 14% 19% 67% Class Structure P1 P2 P3 P4 P5 P6 Total 2019/2020 school year No. -

Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Sep-2018

WWF - DDC Location Plan Sep-2018 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 1 2 Team A King Man Street, Sai Kung (Near Sai Kung Library) Day-Off Team B Chong Yip Shopping Centre Chong Yip Shopping Centre Team C Quarry Bay MTR Station Exit B Bridge Quarry Bay MTR Station Exit B Bridge Team D Tsim Sha Tsui East (Near footbridge) Tsim Sha Tsui East (Near footbridge) Team E Citic Tower, Admiralty (Near footbridge) Citic Tower, Admiralty (Near footbridge) Team F Wanchai Sports Centre (Near footbridge) Wanchai Sports Centre (Near footbridge) Team G Kwai Hing MTR Station (Near footbridge) Kwai Hing MTR Station (Near footbridge) Team H Mong Kok East MTR Station Mong Kok East MTR Station Team I V City, Tuen Mun V City, Tuen Mun Team J Ngau Tau Kok MTR Exit B (Near tunnel) Ngau Tau Kok MTR Exit B (Near tunnel) Team K Kwun Chung Sports Centre Kwun Chung Sports Centre Team L Tai Yau Building, Wan Chai Tai Yau Building, Wan Chai Team M Hiu Kwong Street Sports Centre, Kwun Tong Hiu Kwong Street Sports Centre, Kwun Tong Team N Tiu Keng Leng MTR Station Exit B Tiu Keng Leng MTR Station Exit B Team O Lockhart Road Public Library, Wan Chai Lockhart Road Public Library, Wan Chai Team P Leighton Centre, Causeway Bay Leighton Centre, Causeway Bay Team Q AIA Tower, Fortress Hill AIA Tower, Fortress Hill Team R Chai Wan Sports Centre Front door Chai Wan Sports Centre Front door Team S 21 Shan Mei Street, Fo Tan 21 Shan Mei Street, Fo Tan 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Cheung Sha Wan Road (near Cheung Sha Wan Tsing Hoi Circuit, Tuen Mun Team A Russell Street, Causeway Bay Castle Peak Road, -

Caroline Yi Cheng

CAROLINE YI CHENG 1A, Lane 180 Shaanxi Nan Lu Shanghai, 200031, PR China Tel: (8621) 6445 0902 Fax: (8621) 6445 0937 China Mobile: 13818193608 Hong Kong Mobile: 90108613 Email: [email protected] SPECIAL EXHIBITION: 2012 “Spring Blossom” Installations for Van Cleef & Arpels in Paris, Hong Kong, Tokyo SOLO EXHIBITIONS: 2008 “China Blues” The Pottery Workshop Hong Kong 2002 “Glazing China” Grotto Gallery, Hong Kong 1999 “Made in China Blues” The Pottery Workshop, Hong Kong 1995 “Heroine” The Pottery Workshop, Hong Kong 1993 “Seeds of a New Civilization” The Pottery Workshop, Hong Kong 1992 “Made in Hong Kong” Modernology Gallery, San Francisco, USA 1991 “Essence of Goofy Figures” The Pottery Workshop, Hong Kong GROUP EXHIBITIONS: 2013 “New Blue and White” Boston Museum of Fine Arts, USA 2012 “China’s White Gold” Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK “New Site-East Asian Contemporary Ceramics Exhibition” Yingge Ceramics Museum “Chinese Design Today” Themes and Variations Gallery, London, UK “Push Play” NCECA Invitational, Bellevue Art Museum Seattle The Pottery Workshop 25 Years Exhibition, NCECA Seattle “New ‘China’ Porcelain Art from Jingdezhen” The China Institute, New York City, USA Exhibition at the Westerwald Keramik Museum, Hohr-Grenhausen, Germany Korea Ceramic Exhibition, Hanyang University, Seoul New York Asia Week, Dai Ichi Arts “Eighth Ceramic Biennial”, Hangzhou China “Elements – Irish/Chinese Ceramic & Glass Exhibition” Shengling Gallery, Shanghai 2011 “Mirage-Ceramic Experiments with Contemporary Nomads” Duolun Museum of -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(4)88/13-14 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB4/PL/ITB/1 Panel on Information Technology and Broadcasting Minutes of special meeting held on Tuesday, 25 June 2013, at 8:30 am in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex Members present : Hon WONG Yuk-man (Chairman) Hon James TO Kun-sun Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon WONG Ting-kwong, SBS, JP Hon Ronny TONG Ka-wah, SC Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Hon Mrs Regina IP LAU Suk-yee, GBS, JP Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun, JP Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Hon Albert CHAN Wai-yip Hon Claudia MO Hon YIU Si-wing Hon MA Fung-kwok, SBS, JP Hon Charles Peter MOK Hon CHAN Chi-chuen Members attending : Hon LEE Cheuk-yan Hon WU Chi-wai, MH Hon Gary FAN Kwok-wai Hon IP Kin-yuen Action - 2 - Members absent : Dr Hon Elizabeth QUAT, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon Steven HO Chun-yin Hon SIN Chung-kai, SBS, JP Ir Dr Hon LO Wai-kwok, BBS, MH, JP Hon Christopher CHUNG Shu-kun, BBS, MH, JP Public officers : Agenda item I attending Miss Susie HO, JP Permanent Secretary for Commerce and Economic Development (Communications and Technology) Mr Joe WONG, JP Deputy Secretary for Commerce and Economic Development (Communications and Technology) Radio Television Hong Kong Mr Roy TANG, JP Director of Broadcasting Mr TAI Keen-man Deputy Director of Broadcasting (Programmes) Attendance by : Agenda item I invitation Radio Television Hong Kong Programme Staff Union Ms Janet MAK Former Chairperson of Union Ms CHOI Toi-ling Committee Member Civic Party Ms Bonnie LEUNG Exco Member Action