Physical Sciences and Engineering 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Change and the Selective Signature of the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction

Climate change and the selective signature of the Late Ordovician mass extinction Seth Finnegana,b,1, Noel A. Heimc, Shanan E. Petersc, and Woodward W. Fischera aDivision of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, 1200 East California Boulevard, Pasadena, CA 91125; bDepartment of Integrative Biology, University of California, 1005 Valley Life Sciences Bldg #3140, Berkeley, CA 94720; and cDepartment of Geoscience, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1215 West Dayton Street, Madison, WI 53706 Edited by Richard K. Bambach, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C., and accepted by the Editorial Board March 6, 2012 (received for review October 14, 2011) Selectivity patterns provide insights into the causes of ancient ex- sedimentary record (common cause hypothesis) (14). For the tinction events. The Late Ordovician mass extinction was related LOME, it is useful to split common cause into two hypotheses. to Gondwanan glaciation; however, it is still unclear whether ele- The eustatic common cause hypothesis postulates that Gondwa- vated extinction rates were attributable to record failure, habitat nan glaciation drove the extinction by lowering eustatic sea level, loss, or climatic cooling. We examined Middle Ordovician-Early thereby reducing the overall area of shallow marine habitats, Silurian North American fossil occurrences within a spatiotempo- reorganizing habitat mosaics, and disrupting larval dispersal cor- rally explicit stratigraphic framework that allowed us to quantify ridors (16–18). The climatic common cause hypothesis postulates rock record effects on a per-taxon basis and assay the interplay of that climate cooling, in addition to being ultimately responsible macrostratigraphic and macroecological variables in determining for sea-level drawdown and attendant habitat losses, had a direct extinction risk. -

Sandbian) K-Bentonites in Oslo, Norway T ⁎ Eirik G

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 520 (2019) 203–213 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo A new age model for the Ordovician (Sandbian) K-bentonites in Oslo, Norway T ⁎ Eirik G. Balloa, , Lars Eivind Auglanda, Øyvind Hammerb, Henrik H. Svensena a Centre for Earth Evolution and Dynamics (CEED), University of Oslo, Pb. 1028, 0316 Oslo, Norway b Natural History Museum, University of Oslo, Pb. 1172, 0318 Oslo, Norway ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: During the Late Ordovician, large explosive volcanic eruptions deposited worldwide K-bentonites, including the Chronostratigraphy Millbrig and Deicke K-bentonites in North America and the Kinnekulle K-bentonite in Scandinavia. We have Sandbian-Katian boundary studied a classical locality in Oslo containing one of the most complete sections of K-bentonites in Europe. U-Pb dating In a 53 m section of Sandbian age, we discovered 33 individual K-bentonite beds, the most notable beds being Milankovitch the Kinnekulle and the upper Grimstorp K-bentonite. Magnetic susceptibility (MS) measurements on two in- Age model tervals show significant periodicity peaks interpreted as Milankovitch cycles and thus astronomically forced Kinnekulle changes in sediment supply and composition. These cycles fit remarkably well with both the expected Milankovitch periodicities for the Ordovician as well as the radiometric ages presented in this study and may represent one of the most convincing demonstrations of Milankovitch cycles from the lower Paleozoic so far. Five of the K-bentonites have been dated by high-precision chemical abrasion-thermal ionization mass spectrometry (CA-TIMS) U-Pb zircon geochronology, where the Kinnekulle K-bentonite gives an age of 454.06 ± 0.43 Ma. -

Palynology of the Middle Ordovician Hawaz Formation in the Murzuq Basin, South-West Libya

This is a repository copy of Palynology of the Middle Ordovician Hawaz Formation in the Murzuq Basin, south-west Libya. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/125997/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Abuhmida, F.H. and Wellman, C.H. (2017) Palynology of the Middle Ordovician Hawaz Formation in the Murzuq Basin, south-west Libya. Palynology, 41. pp. 31-56. ISSN 0191-6122 https://doi.org/10.1080/01916122.2017.1356393 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Palynology of the Middle Ordovician Hawaz Formation in the Murzuq Basin, southwest Libya Faisal H. Abuhmidaa*, Charles H. Wellmanb aLibyan Petroleum Institute, Tripoli, Libya P.O. Box 6431, bUniversity of Sheffield, Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, Alfred Denny Building, Western Bank, Sheffield, S10 2TN, UK Twenty nine core and seven cuttings samples were collected from two boreholes penetrating the Middle Ordovician Hawaz Formation in the Murzuq Basin, southwest Libya. -

Polar Front Shift and Atmospheric CO During the Glacial Maximum of the Early Paleozoic Icehouse

Polar front shift and atmospheric CO2 during the glacial maximum of the Early Paleozoic Icehouse Thijs R. A. Vandenbrouckea,b,c,1,2, Howard A. Armstronga,1, Mark Williamsd,e,1, Florentin Parisf, Jan A. Zalasiewiczd, Koen Sabbeg, Jaak Nõlvakh, Thomas J. Challandsa,i, Jacques Verniersb, and Thomas Servaisc aPalaeoClimate Group, Department of Earth Sciences, Durham University, Science Labs, Durham, DH1 3LE, United Kingdom; bResearch Unit Palaeontology, Department of Geology, Ghent University, Krijgslaan 281-S8, 9000 Ghent, Belgium; cGéosystèmes, Université Lille 1, Formation de Recherche en Evolution 3298 du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Avenue Paul Langevin, bâtiment SN5, 59655 Villeneuve d’Ascq Cedex, France; dDepartment of Geology, University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester, LE1 7RH, United Kingdom; eBritish Geological Survey, Kingsley Dunham Centre, Keyworth, NG12 5GG, United Kingdom; fGéosciences, Université de Rennes I, Unité Mixte de Recherche 6118 du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Campus de Beaulieu, 35042 Rennes-cedex, France; gProtistology and Aquatic Ecology, Department of Biology, Ghent University, Krijgslaan 281-S8, 9000 Ghent, Belgium; hInstitute of Geology, Tallinn University of Technology, Ehitajate tee 5, 19086 Tallinn, Estonia; and iTotal E&P UK Limited, Geoscience Research Centre, Crawpeel Road, Aberdeen AB12 3FG, United Kingdom Edited by Jeffrey Kiehl, National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO, and accepted by the Editorial Board July 1, 2010 (received for review March 16, 2010) Our new data address the paradox of Late Ordovician glaciation PAL (5). A GCM experiment parameterized with the same p × under supposedly high CO2 (8 to 22 PAL: preindustrial atmo- pCO2 value, high relative sea level, and a modern equator-to-pole spheric level). -

International Stratigraphic Chart

INTERNATIONAL STRATIGRAPHIC CHART ICS International Commission on Stratigraphy Ma Ma Ma Ma Era Era Era Era Age Age Age Age Age Eon Eon Age Eon Age Eon Stage Stage Stage GSSP GSSP GSSA GSSP GSSP Series Epoch Series Epoch Series Epoch Period Period Period Period System System System System Erathem Erathem Erathem Erathem Eonothem Eonothem Eonothem 145.5 ±4.0 Eonothem 359.2 ±2.5 542 Holocene Tithonian Famennian Ediacaran 0.0117 150.8 ±4.0 Upper 374.5 ±2.6 Neo- ~635 Upper Upper Kimmeridgian Frasnian Cryogenian 0.126 ~ 155.6 385.3 ±2.6 proterozoic 850 “Ionian” Oxfordian Givetian Tonian Pleistocene 0.781 161.2 ±4.0 Middle 391.8 ±2.7 1000 Calabrian Callovian Eifelian Stenian Quaternary 1.806 164.7 ±4.0 397.5 ±2.7 Meso- 1200 Gelasian Bathonian Emsian Ectasian proterozoic 2.588 Middle 167.7 ±3.5 Devonian 407.0 ±2.8 1400 Piacenzian Bajocian Lower Pragian Calymmian Pliocene 3.600 171.6 ±3.0 411.2 ±2.8 1600 Zanclean Aalenian Lochkovian Statherian Jurassic 5.332 175.6 ±2.0 416.0 ±2.8 Proterozoic 1800 Messinian Toarcian Pridoli Paleo- Orosirian 7.246 183.0 ±1.5 418.7 ±2.7 2050 Tortonian Pliensbachian Ludfordian proterozoic Rhyacian 11.608 Lower 189.6 ±1.5 Ludlow 421.3 ±2.6 2300 Serravallian Sinemurian Gorstian Siderian Miocene 13.82 196.5 ±1.0 422.9 ±2.5 2500 Neogene Langhian Hettangian Homerian 15.97 199.6 ±0.6 Wenlock 426.2 ±2.4 Neoarchean Burdigalian M e s o z i c Rhaetian Sheinwoodian 20.43 203.6 ±1.5 428.2 ±2.3 2800 Aquitanian Upper Norian Silurian Telychian 23.03 216.5 ±2.0 436.0 ±1.9 P r e c a m b i n P Mesoarchean C e n o z i c Chattian Carnian -

The Ordovician Succession Adjacent to Hinlopenstretet, Ny Friesland, Spitsbergen

1 2 The Ordovician succession adjacent to Hinlopenstretet, Ny Friesland, Spitsbergen 3 4 Björn Kröger1, Seth Finnegan2, Franziska Franeck3, Melanie J. Hopkins4 5 6 Abstract: The Ordovician sections along the western shore of the Hinlopen Strait, Ny 7 Friesland, were discovered in the late 1960s and since then prompted numerous 8 paleontological publications; several of them are now classical for the paleontology of 9 Ordovician trilobites, and Ordovician paleogeography and stratigraphy. Our 2016 expedition 10 aimed in a major recollection and reappraisal of the classical sites. Here we provide a first 11 high-resolution lithological description of the Kirtonryggen and Valhallfonna formations 12 (Tremadocian –Darriwilian), which together comprise a thickness of 843 m, a revised bio-, 13 and lithostratigraphy, and an interpretation of the depositional sequences. We find that the 14 sedimentary succession is very similar to successions of eastern Laurentia; its Tremadocian 15 and early Floian part is composed of predominantly peritidal dolostones and limestones 16 characterized by ribbon carbonates, intraclastic conglomerates, microbial laminites, and 17 stromatolites, and its late Floian to Darriwilian part is composed of fossil-rich, bioturbated, 18 cherty mud-wackestone, skeletal grainstone and shale, with local siltstone and glauconitic 19 horizons. The succession can be subdivided into five third-order depositional sequences, 20 which are interpreted as representing the SAUK IIIB Supersequence known from elsewhere 21 on the Laurentian -

Arctic Strategies and Policies

1 Arctic Strategies and Policies Inventory and Comparative Study Lassi Heininen April 2012 Northern Research Forum 2 Arctic Strategies and Policies: Inventory and Comparative Study © Lassi Heininen, 2011; 2nd edition April 2012 Published by: The Northern Research Forum & The University of Lapland Available at: http://www.nrf.is Author: Lassi Heininen, PhD., University of Lapland, Northern Research Forum Editor: Embla Eir Oddsdóttir, The Northern Research Forum Secretariat Photograps: © Embla Eir Oddsdóttir Printing and binding: University of Lapland Press / Stell, Akureyri, Iceland Layout and design: Embla Eir Oddsdóttir Arc c strategies and policies 3 Contents Introduction – 5 Background – 7 Inventory on Arctic Strategies and State Policies – 13 1. Canada – 13 2. The Kingdom of Denmark – 17 3. Finland – 23 4. Iceland – 29 5. Norway – 35 6. The Russian Federation – 43 7. Sweden – 49 8. The United States of America – 53 9. The European Union – 57 Comparative Study of the Arctic Strategies and State Policies – 67 (Re)constructing, (re)defi ning and (re)mapping – 68 Summary of priorities, priority areas and objectives – 69 Comparative study of priorities/priority areas and objectives – 71 International Cooperation – 77 Conclusions – 79 References – 83 Appendix - tables – 91 Northern Research Forum 4 Arc c strategies and policies 5 tors and dynamics, as well as mapping rela- Introduction onships between indicators. Furthermore, it is relevant to study the Arc c states and their policies, and to explore their changing posi- In the early twenty-fi rst century interna onal on in a globalized world where the role of a en on and global interest in the northern- the Arc c has become increasingly important most regions of the globe are increasing, at in world poli cs. -

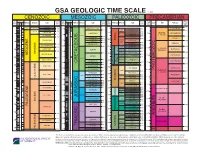

GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE V

GSA GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE v. 4.0 CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST HIST. ANOM. (Ma) ANOM. CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 66.0 541 CALABRIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE* 1.8 31 C31 MAASTRICHTIAN 252 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 Lopin- 254 32 C32 72.1 635 2A C2A PIACENZIAN WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 3.6 gian 33 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN CAPITANIAN NEOPRO- 5 C3 CAMPANIAN Guada- 265 750 CRYOGENIAN 5.3 80 C33 WORDIAN TEROZOIC 3A MESSINIAN LATE lupian 269 C3A 83.6 ROADIAN 272 850 7.2 SANTONIAN 4 KUNGURIAN C4 86.3 279 TONIAN CONIACIAN 280 4A Cisura- C4A TORTONIAN 90 89.8 1000 1000 PERMIAN ARTINSKIAN 10 5 TURONIAN lian C5 93.9 290 SAKMARIAN STENIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 296 SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 ASSELIAN 299 5A 100 100 300 GZHELIAN 1200 C5A 13.8 LATE 304 KASIMOVIAN 307 1250 MESOPRO- 15 LANGHIAN ECTASIAN 5B C5B ALBIAN MIDDLE MOSCOVIAN 16.0 TEROZOIC 5C C5C 110 VANIAN 315 PENNSYL- 1400 EARLY 5D C5D MIOCENE 113 320 BASHKIRIAN 323 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 1500 CALYMMIAN 6 C6 APTIAN LATE 20 120 331 6A C6A 20.4 EARLY 1600 M0r 126 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 MIDDLE VISEAN MISSIS- M3 BARREMIAN SIPPIAN STATHERIAN C6C 23.0 6C 130 M5 CRETACEOUS 131 347 1750 HAUTERIVIAN 7 C7 CARBONIFEROUS EARLY TOURNAISIAN 1800 M10 134 25 7A C7A 359 8 C8 CHATTIAN VALANGINIAN M12 360 140 M14 139 FAMENNIAN OROSIRIAN 9 C9 M16 28.1 M18 BERRIASIAN 2000 PROTEROZOIC 10 C10 LATE -

(Floian) Conodont Fauna from the Eastern Cordillera of Peru (Central Andean Basin) Geologica Acta: an International Earth Science Journal, Vol

Geologica Acta: an international earth science journal ISSN: 1695-6133 [email protected] Universitat de Barcelona España GUTIÉRREZ-MARCO, J.C.; ALBANESI, G.L.; SARMIENTO, G.N.; CARLOTTO, V. An Early Ordovician (Floian) Conodont Fauna from the Eastern Cordillera of Peru (Central Andean Basin) Geologica Acta: an international earth science journal, vol. 6, núm. 2, junio, 2008, pp. 147-160 Universitat de Barcelona Barcelona, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=50513115004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Geologica Acta, Vol.6, Nº 2, June 2008, 147-160 DOI: 10.1344/105.000000248 Available online at www.geologica-acta.com An Early Ordovician (Floian) Conodont Fauna from the Eastern Cordillera of Peru (Central Andean Basin) 1 2 1 3,4 J.C. GUTIÉRREZ-MARCO G.L. ALBANESI G.N. SARMIENTO and V. CARLOTTO 1 Instituto de Geología Económica (CSIC-UCM). Facultad de Ciencias Geológicas 28040 Madrid, Spain. Gutiérrez-Marco E-mail: [email protected] Sarmiento E-mail: [email protected] 2 CONICET-CICTERRA, Museo de Paleontología Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba Casilla de Correo 1598, 5000 Córdoba, Argentina. E-mail: [email protected] 3 INGEMMET Avenida Canadá 1740, San Borja, Lima, Peru. E-mail: [email protected] 4 Departamento de Geología, Universidad Nacional San Antonio Abad del Cusco Avda. de la Cultura 733, Cuzco, Perú ABSTRACT Late Floian conodonts are recorded from a thin limestone lens intercalated in the lower part of the San José For- mation at the Carcel Puncco section (Inambari River), Eastern Cordillera of Peru. -

International Chronostratigraphic Chart

INTERNATIONAL CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHIC CHART www.stratigraphy.org International Commission on Stratigraphy v 2018/08 numerical numerical numerical Eonothem numerical Series / Epoch Stage / Age Series / Epoch Stage / Age Series / Epoch Stage / Age GSSP GSSP GSSP GSSP EonothemErathem / Eon System / Era / Period age (Ma) EonothemErathem / Eon System/ Era / Period age (Ma) EonothemErathem / Eon System/ Era / Period age (Ma) / Eon Erathem / Era System / Period GSSA age (Ma) present ~ 145.0 358.9 ± 0.4 541.0 ±1.0 U/L Meghalayan 0.0042 Holocene M Northgrippian 0.0082 Tithonian Ediacaran L/E Greenlandian 152.1 ±0.9 ~ 635 Upper 0.0117 Famennian Neo- 0.126 Upper Kimmeridgian Cryogenian Middle 157.3 ±1.0 Upper proterozoic ~ 720 Pleistocene 0.781 372.2 ±1.6 Calabrian Oxfordian Tonian 1.80 163.5 ±1.0 Frasnian Callovian 1000 Quaternary Gelasian 166.1 ±1.2 2.58 Bathonian 382.7 ±1.6 Stenian Middle 168.3 ±1.3 Piacenzian Bajocian 170.3 ±1.4 Givetian 1200 Pliocene 3.600 Middle 387.7 ±0.8 Meso- Zanclean Aalenian proterozoic Ectasian 5.333 174.1 ±1.0 Eifelian 1400 Messinian Jurassic 393.3 ±1.2 7.246 Toarcian Devonian Calymmian Tortonian 182.7 ±0.7 Emsian 1600 11.63 Pliensbachian Statherian Lower 407.6 ±2.6 Serravallian 13.82 190.8 ±1.0 Lower 1800 Miocene Pragian 410.8 ±2.8 Proterozoic Neogene Sinemurian Langhian 15.97 Orosirian 199.3 ±0.3 Lochkovian Paleo- 2050 Burdigalian Hettangian 201.3 ±0.2 419.2 ±3.2 proterozoic 20.44 Mesozoic Rhaetian Pridoli Rhyacian Aquitanian 423.0 ±2.3 23.03 ~ 208.5 Ludfordian 2300 Cenozoic Chattian Ludlow 425.6 ±0.9 Siderian 27.82 Gorstian -

International Chronostratigraphic Chart

INTERNATIONAL CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHIC CHART www.stratigraphy.org International Commission on Stratigraphy v 2014/02 numerical numerical numerical Eonothem numerical Series / Epoch Stage / Age Series / Epoch Stage / Age Series / Epoch Stage / Age Erathem / Era System / Period GSSP GSSP age (Ma) GSSP GSSA EonothemErathem / Eon System / Era / Period EonothemErathem / Eon System/ Era / Period age (Ma) EonothemErathem / Eon System/ Era / Period age (Ma) / Eon GSSP age (Ma) present ~ 145.0 358.9 ± 0.4 ~ 541.0 ±1.0 Holocene Ediacaran 0.0117 Tithonian Upper 152.1 ±0.9 Famennian ~ 635 0.126 Upper Kimmeridgian Neo- Cryogenian Middle 157.3 ±1.0 Upper proterozoic Pleistocene 0.781 372.2 ±1.6 850 Calabrian Oxfordian Tonian 1.80 163.5 ±1.0 Frasnian 1000 Callovian 166.1 ±1.2 Quaternary Gelasian 2.58 382.7 ±1.6 Stenian Bathonian 168.3 ±1.3 Piacenzian Middle Bajocian Givetian 1200 Pliocene 3.600 170.3 ±1.4 Middle 387.7 ±0.8 Meso- Zanclean Aalenian proterozoic Ectasian 5.333 174.1 ±1.0 Eifelian 1400 Messinian Jurassic 393.3 ±1.2 7.246 Toarcian Calymmian Tortonian 182.7 ±0.7 Emsian 1600 11.62 Pliensbachian Statherian Lower 407.6 ±2.6 Serravallian 13.82 190.8 ±1.0 Lower 1800 Miocene Pragian 410.8 ±2.8 Langhian Sinemurian Proterozoic Neogene 15.97 Orosirian 199.3 ±0.3 Lochkovian Paleo- Hettangian 2050 Burdigalian 201.3 ±0.2 419.2 ±3.2 proterozoic 20.44 Mesozoic Rhaetian Pridoli Rhyacian Aquitanian 423.0 ±2.3 23.03 ~ 208.5 Ludfordian 2300 Cenozoic Chattian Ludlow 425.6 ±0.9 Siderian 28.1 Gorstian Oligocene Upper Norian 427.4 ±0.5 2500 Rupelian Wenlock Homerian -

Revised Sequence Stratigraphy of the Ordovician of Baltoscandia …………………………………………… 20 Druzhinina, O

Baltic Stratigraphical Association Department of Geology, Faculty of Geography and Earth Sciences, University of Latvia Natural History Museum of Latvia THE EIGHTH BALTIC STRATIGRAPHICAL CONFERENCE ABSTRACTS Edited by E. Lukševičs, Ģ. Stinkulis and J. Vasiļkova Rīga, 2011 The Eigth Baltic Stratigraphical Conference 28 August – 1 September 2011, Latvia Abstracts Edited by E. Lukševičs, Ģ. Stinkulis and J. Vasiļkova Scientific Committee: Organisers: Prof. Algimantas Grigelis (Vilnius) Baltic Stratigraphical Association Dr. Olle Hints (Tallinn) Department of Geology, University of Latvia Dr. Alexander Ivanov (St. Petersburg) Natural History Museum of Latvia Prof. Leszek Marks (Warsaw) Northern Vidzeme Geopark Prof. Tõnu Meidla (Tartu) Dr. Jonas Satkūnas (Vilnius) Prof. Valdis Segliņš (Riga) Prof. Vitālijs Zelčs (Chairman, Riga) Recommended reference to this publication Ceriņa, A. 2011. Plant macrofossil assemblages from the Eemian-Weichselian deposits of Latvia and problems of their interpretation. In: Lukševičs, E., Stinkulis, Ģ. and Vasiļkova, J. (eds). The Eighth Baltic Stratigraphical Conference. Abstracts. University of Latvia, Riga. P. 18. The Conference has special sessions of IGCP Project No 591 “The Early to Middle Palaeozoic Revolution” and IGCP Project No 596 “Climate change and biodiversity patterns in the Mid-Palaeozoic (Early Devonian to Late Carboniferous)”. See more information at http://igcl591.org. Electronic version can be downloaded at www.geo.lu.lv/8bsc Hard copies can be obtained from: Department of Geology, Faculty of Geography and Earth Sciences, University of Latvia Raiņa Boulevard 19, Riga LV-1586, Latvia E-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-9984-45-383-5 Riga, 2011 2 Preface Baltic co-operation in regional stratigraphy is active since the foundation of the Baltic Regional Stratigraphical Commission (BRSC) in 1969 (Grigelis, this volume).