Selected Cuts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self-Determined Family Living Division

2009 Clark County Fair Exhibitor Handbook 4-H Family & Consumer Science Division Page 21 of 48 SELF-DETERMINED FAMILY LIVING DIVISION SPINNING Superintendent: Deborah Reida (360) 687-5274 CLASS 675: BLENDING FIBERS 1. On a 3”x 5” index card, state your age and how long you’ve been enrolled in the spinning project. 2. Must provide clean, uncarded fibers of the same fibers used to produce the exhibit. Put the index card and fibers into a small ziplock bag, and attach this to the exhibit. 3. Lots A through E, submit three (3) rolag for each lot. 4. Lots F through J, submit 1 batt for each lot. Points: Blue-7, Red-5, White-3. LOTS: A. Sheep wool/sheep wool - hand carded B. Sheep wool/animal fibers - hand carded C. Sheep wool/natural fibers - hand carded D. Sheep wool/synthetic fibers - hand carded E. Other - hand carded F. Sheep wool/sheep wool - drum carded G. Sheep wool/animal fibers - drum carded H. Sheep wool/natural fibers - drum carded I. Sheep wool/synthetic fibers - drum carded J. Other - drum carded CLASS 680: ROLAGS Have the following information for each exhibit: 1. On a 3”x 5” index card, state your age and how long you have been enrolled in the spinning project. 2. Must provide clean fiber(s) used to produce the exhibit. 3. Lots A through C- submit three (3) rolags each. Put the index card and fibers into a small ziplock bag, and attach this to the exhibit. Points: Blue-6, Red-4, White-2. LOTS: A. -

Lesson 6.Pmd

Natural Ecosystem MODULE - 2 Ecological Concepts and Issues 6 Notes NATURAL ECOSYSTEM Whenever you travel long distance you come across changing patterns of landscape. As you move out from your city or village, you see croplands, grasslands, or in some areas a forests, desert or a mountainous region. These distinct landscapes are differentiated primarily due to the type of vegetation in these areas. Physical and geographical factors such as rainfall, temperature, elevation, soil type etc. determine the nature of the vegetation. In this lesson you will learn about the natural ecosystems with their varied vegetation and associated wildlife. OBJECTIVES After completing this lesson, you will be able to: • list the various natural ecosystems; • describe the various terrestrial ecosystems; • describe the various aquatic ecosystems (fresh water, marine and estuarine); • recognize ecotones, their significance and the edge effect. • list the major Indian ecosystems; • list the threatened ecosystems-mangrove, wetlands, coastal ecosystems and islands; • explain the need and methods of conservation of natural ecosystems. 6.1 WHAT ARE NATURAL ECOSYSTEMS A natural ecosystem is an assemblage of plants and animals which functions as a unit and is capable of maintaining its identity such as forest, grassland, an estuary, human intervention is an example of a natural ecosystem. A natural ecosystem is totally dependent on solar energy. There are two main categories of ecosystems. 95 MODULE - 2 Environmental Science Senior Secondary Course Ecological Concepts and Issues (1) Terrestrial ecosystem: Ecosystems found on land e.g. forest, grasslands, deserts, tundra. (2) Aquatic ecosystem: Plants and animal community found in water bodies. These can be further classified into two sub groups. -

Smart Border Management: Indian Coastal and Maritime Security

Contents Foreword p2/ Preface p3/ Overview p4/ Current initiatives p12/ Challenges and way forward p25/ International examples p28/Sources p32/ Glossary p36/ FICCI Security Department p38 Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security September 2017 www.pwc.in Dr Sanjaya Baru Secretary General Foreword 1 FICCI India’s long coastline presents a variety of security challenges including illegal landing of arms and explosives at isolated spots on the coast, infiltration/ex-filtration of anti-national elements, use of the sea and off shore islands for criminal activities, and smuggling of consumer and intermediate goods through sea routes. Absence of physical barriers on the coast and presence of vital industrial and defence installations near the coast also enhance the vulnerability of the coasts to illegal cross-border activities. In addition, the Indian Ocean Region is of strategic importance to India’s security. A substantial part of India’s external trade and energy supplies pass through this region. The security of India’s island territories, in particular, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, remains an important priority. Drug trafficking, sea-piracy and other clandestine activities such as gun running are emerging as new challenges to security management in the Indian Ocean region. FICCI believes that industry has the technological capability to implement border management solutions. The government could consider exploring integrated solutions provided by industry for strengthening coastal security of the country. The FICCI-PwC report on ‘Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security’ highlights the initiatives being taken by the Central and state governments to strengthen coastal security measures in the country. -

Diversity of Malacofauna from the Paleru and Moosy Backwaters Of

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2017; 5(4): 881-887 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 JEZS 2017; 5(4): 881-887 Diversity of Malacofauna from the Paleru and © 2017 JEZS Moosy backwaters of Prakasam district, Received: 22-05-2017 Accepted: 23-06-2017 Andhra Pradesh, India Darwin Ch. Department of Zoology and Aquaculture, Acharya Darwin Ch. and P Padmavathi Nagarjuna University Nagarjuna Nagar, Abstract Andhra Pradesh, India Among the various groups represented in the macrobenthic fauna of the Bay of Bengal at Prakasam P Padmavathi district, Andhra Pradesh, India, molluscs were the dominant group. Molluscs were exploited for Department of Zoology and industrial, edible and ornamental purposes and their extensive use has been reported way back from time Aquaculture, Acharya immemorial. Hence the present study was focused to investigate the diversity of Molluscan fauna along Nagarjuna University the Paleru and Moosy backwaters of Prakasam district during 2016-17 as these backwaters are not so far Nagarjuna Nagar, explored for malacofauna. A total of 23 species of molluscs (16 species of gastropods belonging to 12 Andhra Pradesh, India families and 7 species of bivalves representing 5 families) have been reported in the present study. Among these, gastropods such as Umbonium vestiarium, Telescopium telescopium and Pirenella cingulata, and bivalves like Crassostrea madrasensis and Meretrix meretrix are found to be the most dominant species in these backwaters. Keywords: Malacofauna, diversity, gastropods, bivalves, backwaters 1. Introduction Molluscans are the second largest phylum next to Arthropoda with estimates of 80,000- 100,000 described species [1]. These animals are soft bodied and are extremely diversified in shape and colour. -

Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman by Global Ocean Associates Prepared for Office of Naval Research – Code 322 PO

An Atlas of Oceanic Internal Solitary Waves (February 2004) Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman by Global Ocean Associates Prepared for Office of Naval Research – Code 322 PO Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman Overview The Arabian Sea is located in the northwest Indian Ocean. It is bounded by India (to the east), Iran (to the north) and the Arabian Peninsula (in the west)(Figure 1). The Gulf of Oman is located in the northwest corner of the Arabian Sea. The continental shelf in the region is widest off the northwest coast of India, which also experiences wind-induced upwelling. [LME, 2004]. The circulation in the Arabian Sea is affected by the Northeast (March-April) and Southwest (September -October) Monsoon seasons [Tomczak et al. 2003]. Figure 1. Bathymetry of Arabian Sea [Smith and Sandwell, 1997]. 501 An Atlas of Oceanic Internal Solitary Waves (February 2004) Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman by Global Ocean Associates Prepared for Office of Naval Research – Code 322 PO Observations There has been some scientific study of internal waves in the Arabian Sea and Gulf of Oman through the use of satellite imagery [Zheng et al., 1998; Small and Martin, 2002]. The imagery shows evidence of fine scale internal wave signatures along the continental shelf around the entire region. Table 1 shows the months of the year when internal wave observations have been made. Table 1 - Months when internal waves have been observed in the Arabian Sea and Gulf of Oman (Numbers indicate unique dates in that month when waves have been noted) Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec 2 552 1251 Small and Martin [2002] reported on internal wave signatures observed in ERS SAR images of the Gulf of Oman. -

Plinius Senior Naturalis Historia Liber V

PLINIUS SENIOR NATURALIS HISTORIA LIBER V 1 Africam Graeci Libyam appellavere et mare ante eam Libycum; Aegyptio finitur, nec alia pars terrarum pauciores recipit sinus, longe ab occidente litorum obliquo spatio. populorum eius oppidorumque nomina vel maxime sunt ineffabilia praeterquam ipsorum linguis, et alias castella ferme inhabitant. 2 Principio terrarum Mauretaniae appellantur, usque ad C. Caesarem Germanici filium regna, saevitia eius in duas divisae provincias. promunturium oceani extumum Ampelusia nominatur a Graecis. oppida fuere Lissa et Cottae ultra columnas Herculis, nunc est Tingi, quondam ab Antaeo conditum, postea a Claudio Caesare, cum coloniam faceret, appellatum Traducta Iulia. abest a Baelone oppido Baeticae proximo traiectu XXX. ab eo XXV in ora oceani colonia Augusti Iulia Constantia Zulil, regum dicioni exempta et iura in Baeticam petere iussa. ab ea XXXV colonia a Claudio Caesare facta Lixos, vel fabulosissime antiquis narrata: 3 ibi regia Antaei certamenque cum Hercule et Hesperidum horti. adfunditur autem aestuarium e mari flexuoso meatu, in quo dracones custodiae instar fuisse nunc interpretantur. amplectitur intra se insulam, quam solam e vicino tractu aliquanto excelsiore non tamen aestus maris inundant. exstat in ea et ara Herculis nec praeter oleastros aliud ex narrato illo aurifero nemore. 4 minus profecto mirentur portentosa Graeciae mendacia de his et amne Lixo prodita qui cogitent nostros nuperque paulo minus monstrifica quaedam de iisdem tradidisse, praevalidam hanc urbem maioremque Magna Carthagine, praeterea ex adverso eius sitam et prope inmenso tractu ab Tingi, quaeque alia Cornelius Nepos avidissime credidit. 5 ab Lixo XL in mediterraneo altera Augusta colonia est Babba, Iulia Campestris appellata, et tertia Banasa LXXV p., Valentia cognominata. -

Application of Tetraether Membrane Lipids As Proxies for Continental Climate

Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Application of tetraether membrane lipids as proxies for continental climate reconstruction in Iberian and Siberian lakes Marina Escala Pascual Tesi doctoral Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Application of tetraether membrane lipids as proxies for continental climate reconstruction in Iberian and Siberian lakes Memòria presentada per Marina Escala Pascual per optar al títol de Doctor per la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, sota la direcció del doctor Antoni Rosell Melé. Marina Escala Pascual Abril 2009 Cover photograph: Lake Baikal (Jens Klump, Continent Project) Als meus pares i al meu germà. INDEX Acknowledgements .................................................................................i Abstract .................................................................................................iii Resum ....................................................................................................iv Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1. Paleoclimate and biomarker proxies ....................................................3 1.2. Distribution of Archaea in freshwater environments ........................5 1.3. Origin and significance of GDGTs .......................................................9 1.4. Calibration of GDGT-based proxies ..................................................14 1.5. Objective and outline of this thesis ....................................................19 Chapter 2 Methodology 2.1. -

Sardegna Punica

BIBLIOTHECA SARDA N. 56 Gennaro Pesce SARDEGNA PUNICA a cura di Raimondo Zucca In copertina: Federico Melis, Cavaliere, 1928 INDICE 7 Prefazione 219 Betili 28 Nota biografica 222 Statuette e altri oggetti in bronzo 39 Nota bibliografica 230 Scultura in legno 45 Avvertenze redazionali 231 Plastica in terracotta SARDEGNA PUNICA 265 La stipe votiva di Bithia Riedizione dell’opera: 276 I vasi di terracotta Sardegna punica, Cagliari, 49 Premessa Fratelli Fossataro, 1961. 293 Ori e argenti 53 I Fenici in Occidente 299 Le gemme 60 I Fenici in Sardegna 304 Amuleti 69 Cartagine e il suo mondo Pesce, Gennaro 306 Oggetti in osso Sardegna punica / Gennaro Pesce ; 77 Sardegna punica a cura di Raimondo Zucca. - Nuoro : Ilisso, c2000. 334 p. : ill. ; 18 cm. - (Bibliotheca sarda ; 56). 308 Vetri 1. Cartaginesi - Civiltà - Sardegna 84 Gli dei I. Zucca, Raimondo 316 Piombo e ferro 937.9 89 Le città 317 Monete Scheda catalografica: 99 I documenti scritti Cooperativa per i Servizi Bibliotecari, Nuoro 321 Uova di struzzo e valve 105 L’architettura: i templi di conchiglia 159 Le tombe 323 Valore della civiltà puni- 171 La casa d’abitazione ca in Sardegna 325 Le fonti letterarie sulla sto- © Copyright 2000 179 La statuaria by ILISSO EDIZIONI - Nuoro ria sarda prima del domi- ISBN 88-87825-13-0 191 Sculture a rilievo nio romano PREFAZIONE Allorquando il 6 gennaio 1949 assunse la reggenza della Soprintendenza alle Antichità della Sardegna, Genna- ro Pesce diveniva il decimo soprintendente della storia dell’archeologia nell’isola, dal momento che il primo Com- missario ai Musei e Scavi della Sardegna (come allora si di- cevano i responsabili delle Antichità), il canonico Giovanni Spano, era entrato ufficialmente in possesso della sua cari- ca nel 1875, lo stesso anno dell’istituzione del Commissaria- to con R.D. -

Copyrighted Material

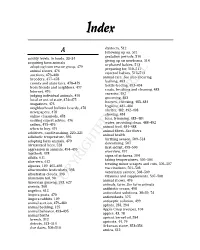

Index dystocia, 512 A following up on, 511 gestation periods, 510 acidity levels, in foods, 33–34 giving up on newborns, 514 acquiring farm animals orphaned babies, 513 adopting from rescue group, 479 preparing for, 510–511 animal shows, 476 rejected babies, 512–513 auctions, 479–480 animal care. See also shearing breeders, 477–478 bathing, 483 county and state fairs, 478–479 bottle-feeding, 493–494 from friends and neighbors, 477 coats, brushing and cleaning, 483 Internet, 476 exercise, 492 judging individual animals, 476 grooming, 483 local or out of state, 474–475 hooves, checking, 483–484 magazines, 476 hygiene, 481–484 neighborhood bulletin boards, 478 shelter, 482, 492–493 newspapers, 478 shoeing, 484 online classifi eds, 478 toes, trimming, 483–484 seeking expert advice, 476 water, providing clean, 488–492 sellers, 475–476 animal feed, 484–488 when to buy, 474 animal fi bers. See fi bers additives, candle-making, 220–221 animal health adiabatic temperature, 395 birthing season, 509–514 adopting farm animals, 479 deworming, 507 Africanized bees, 528 fi rst-aid kit, 498–500 aggression in animals, 494–495 overview, 497 AgriSeek, 478 signs of sickness, 504 alfalfa, 611 taking temperatures, 505–506 aloe vera, 612 treating minor scrapes and cuts, 506–507 alpacas, 109, 465–466 vaccinations, 501–503 altocumulus lenticularis, 393 veterinary service, 508–509 altostratus clouds, 393 vitamins and supplements, 507–508 aluminum foil, 90 animal shows, 476 American ginseng, 593, 627 animals, farm. See farm animals anemia, 560 COPYRIGHTEDantibiotic -

Russia and Siberia: the Beginning of the Penetration of Russian People Into Siberia, the Campaign of Ataman Yermak and It’S Consequences

The Aoyama Journal of International Politics, Economics and Communication, No. 106, May 2021 CCCCCCCCC Article CCCCCCCCC Russia and Siberia: The Beginning of the Penetration of Russian People into Siberia, the Campaign of Ataman Yermak and it’s Consequences Aleksandr A. Brodnikov* Petr E. Podalko** The penetration of the Russian people into Siberia probably began more than a thousand years ago. Old Russian chronicles mention that already in the 11th century, the northwestern part of Siberia, then known as Yugra1), was a “volost”2) of the Novgorod Land3). The Novgorod ush- * Associate Professor, Novosibirsk State University ** Professor, Aoyama Gakuin University 1) Initially, Yugra was the name of the territory between the mouth of the river Pechora and the Ural Mountains, where the Finno-Ugric tribes historically lived. Gradually, with the advancement of the Russian people to the East, this territorial name spread across the north of Western Siberia to the river Taz. Since 2003, Yugra has been part of the offi cial name of the Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug: Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug—Yugra. 2) Volost—from the Old Russian “power, country, district”—means here the territo- rial-administrative unit of the aboriginal population with the most authoritative leader, the chief, from whom a certain amount of furs was collected. 3) Novgorod Land (literally “New City”) refers to a land, also known as “Gospodin (Lord) Veliky (Great) Novgorod”, or “Novgorod Republic”, with its administrative center in Veliky Novgorod, which had from the 10th century a tendency towards autonomy from Kiev, the capital of Ancient Kievan Rus. From the end of the 11th century, Novgorod de-facto became an independent city-state that subdued the entire north of Eastern Europe. -

Bibliography of H. FRUHSTORFER

Nachrichten des entomologischen Vereins Apollo (e. V, gegr. 1897) Supplementum 1985 Frankfurt/M. ISSN 0723-9920 Nachrichten des entomologischen Vereins Apollo Herausgeber Entomologischer Verein Apollo (e. V.), Frankfurt am Main, ge gründet 1897. 1. Vorsitzender Klaus G. Schurian, Altkönigstraße 14a, 6231 Sulzbach/Ts., verant wortlich im Sinne des Presserechts. RedaktionskomiteeWolfgang Eckweiler, Gronauer Straße 40 , 6000 Frankfurt; Ernst Görgner, Gronauer Straße 40, 6000 Frankfurt; Peter Hofmann, Berg straße 40, 6477 Limeshain 3; Wolfgang Nässig, Postfach 3063, 6052 Mühlheim 3; Klaus G.Schurian, Altkönigstraße 14a,6231 Sulzbach/Ts. Manuskripte an Klaus G. Schurian, Altkönigstraße 14a, 6231 Sulzbach/Ts. Das Copy right der abgedruckten Beiträge liegt beim Entomologischen Verein Apollo e. V., Frankfurt am Main. Inhalt Die Autoren sind für den Inhalt ihrer Beiträge allein verantwortlich; die Artikel geben nicht notwendigerweise die Meinung der Redaktion oder des Vereins wieder. Freiexemplare Die Autoren erhalten 50 Freiexemplare; werden weitere Exemplare zum Selbstkostenpreis gewünscht, so ist dies beim Einreichen des Manuskriptes zu vermerken. Farbtafeln Prinzipiell besteht die Möglichkeit, auch Farbtafeln drucken zu las sen. Die Finanzierung solcher Tafeln kann allerdings nicht durch den Verein erfolgen, sondern muß durch den Autor des Artikels organi siert werden. Die Bearbeitung ist ziemlich zeitaufwendig, ,,Eilaufträ ge" sind leider nicht möglich. Interessierte Autoren wenden sich bitte an K. G. Schurian oder W. Nässig. Abonnement Jahresbeitrag z. Zt. DM 20,—, Schüler und Studenten DM 10,—; Aufnahmegebühr DM 2 ,—. Im Ausland zuzüglich Porto. Anfragen an die Mitglieder des Redaktionskomitees. Einzelpreis Supplementum 5: DM 20,— pro Heft (im Ausland plus Porto). Be stellungen an den 1. Schriftführer Wolfgang Nässig, Postfach 3063, 6052 Mühlheim 3. -

Arrian's Voyage Round the Euxine

— T.('vn.l,r fuipf ARRIAN'S VOYAGE ROUND THE EUXINE SEA TRANSLATED $ AND ACCOMPANIED WITH A GEOGRAPHICAL DISSERTATION, AND MAPS. TO WHICH ARE ADDED THREE DISCOURSES, Euxine Sea. I. On the Trade to the Eqft Indies by means of the failed II. On the Di/lance which the Ships ofAntiquity ufually in twenty-four Hours. TIL On the Meafure of the Olympic Stadium. OXFORD: DAVIES SOLD BY J. COOKE; AND BY MESSRS. CADELL AND r STRAND, LONDON. 1805. S.. Collingwood, Printer, Oxford, TO THE EMPEROR CAESAR ADRIAN AUGUSTUS, ARRIAN WISHETH HEALTH AND PROSPERITY. We came in the courfe of our voyage to Trapezus, a Greek city in a maritime fituation, a colony from Sinope, as we are in- formed by Xenophon, the celebrated Hiftorian. We furveyed the Euxine fea with the greater pleafure, as we viewed it from the lame fpot, whence both Xenophon and Yourfelf had formerly ob- ferved it. Two altars of rough Hone are ftill landing there ; but, from the coarfenefs of the materials, the letters infcribed upon them are indiftincliy engraven, and the Infcription itfelf is incor- rectly written, as is common among barbarous people. I deter- mined therefore to erect altars of marble, and to engrave the In- fcription in well marked and diftinct characters. Your Statue, which Hands there, has merit in the idea of the figure, and of the defign, as it reprefents You pointing towards the fea; but it bears no refemblance to the Original, and the execution is in other re- fpects but indifferent. Send therefore a Statue worthy to be called Yours, and of a fimilar delign to the one which is there at prefent, b as 2 ARYAN'S PERIPLUS as the fituation is well calculated for perpetuating, by thefe means, the memory of any illuftrious perfon.