Religious Diversity in a New Australian Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Believing in Fiction I

Believing in Fiction i The Rise of Hyper-Real Religion “What is real? How do you define real?” – Morpheus, in The Matrix “Television is reality, and reality is less than television.” - Dr. Brian O’Blivion, in Videodrome by Ian ‘Cat’ Vincent ver since the advent of modern mass communication and the resulting wide dissemination of popular culture, the nature and practice of religious belief has undergone a Econsiderable shift. Especially over the last fifty years, there has been an increasing tendency for pop culture to directly figure into the manifestation of belief: the older religious faiths have either had to partly embrace, or strenuously oppose, the deepening influence of books, comics, cinema, television and pop music. And, beyond this, new religious beliefs have arisen that happily partake of these media 94 DARKLORE Vol. 8 Believing in Fiction 95 – even to the point of entire belief systems arising that make no claim emphasises this particularly in his essay Simulacra and Simulation.6 to any historical origin. Here, he draws a distinction between Simulation – copies of an There are new gods in the world – and and they are being born imitation or symbol of something which actually exists – and from pure fiction. Simulacra – copies of something that either no longer has a physical- This is something that – as a lifelong fanboy of the science fiction, world equivalent, or never existed in the first place. His view was fantasy and horror genres and an exponent of a often pop-culture- that modern society is increasingly emphasising, or even completely derived occultism for nearly as long – is no shock to me. -

Book Review:" Hinduism and Christianity"

Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies Volume 7 Article 12 January 1994 Book Review: "Hinduism and Christianity" Anand Amaladass Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jhcs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Amaladass, Anand (1994) "Book Review: "Hinduism and Christianity"," Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies: Vol. 7, Article 12. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1100 The Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies is a publication of the Society for Hindu-Christian Studies. The digital version is made available by Digital Commons @ Butler University. For questions about the Journal or the Society, please contact [email protected]. For more information about Digital Commons @ Butler University, please contact [email protected]. Amaladass: Book Review: "Hinduism and Christianity" BOOK REVIEWS Hinduism and Christianity. John Brockington. London: Macmillan, 1992, xiii +215pp. IN A SERIES of monographs on themes in both. So juxtaposing the development of a theme comparative religion under the general editorship in two traditions will reveal this factor. But the of Glyn Richards the first published title is lack of development of a particular theme in a Hinduism and Christianity by John Brockington. given tradition does not mean much in This volume contains a selection of themes from comparison with another where this theme is Hinduism and Christianity. It is intended for well developed. Hence some statements of such many Christians in Europe and America whose comparative nature do sound ambiguous in this everyday experience does not include the book. For instance, it is said that "there is existence of several major religions. Obviously virtually no trace within Hinduism of the in a volume of about 200 pages one cannot fellowship at a common meal found in many expect a detailed discussion on the selected other religions" (p.122), the author adds themes. -

The Teachings of the Prajapita Brahma Kumaris Movement

IJT 44/1&2 (2002), pp. 94-106 The Teachings of the Pra.japita Brahma Kumaris Movement Bed Singh* The Prajapita Brahma Kumaris Movement was founded by a prosperous Sindhi businessman named Lekhraj. It is probably significant however that his trade was in Jewellery. 1 After Dada Lekhraj's personal experience with God Shiva, he was used as a medium to reveal the mysteries of the self and the work order. These experiences brought about a tremendous change in him to whom God Shiva gave the name "Prajapita Brahma". In 1937 he laid the foundations ofthe Movement."2 After Dada Lekhraj's personal experience with God, he started a regular satsang (fellowship) in Hyderabad after laying the foundation of the Movement. The satsang came to be known as "Om Mandi".3 Around 300 devotees started gathering in the Satsang. After the Independence oflndia, many devotees left Hyderabad and shifted to India. On the request of many devotees in India the headquarters of the Movement was shifted to India in 19 51. 4 The Prajapita Brahmakumaris Ishwariya Vishwa Vidyalaya's Report upto 1983 at a glance is as follows. Dedicated sisters (Kumaris) 1095 Dedicated brothers (Kumars) 200 Single sisters 15230 Single brothers 9150 Married sisters 51175 Married brothers 51575 Children 20000 Total number of devotees 1,49095 Spiritual Museum 110 Spiritual Centres 325 Overseas Centres 100 Sub-centres 825 Total number of centres 13505 * Rev. Bed Singh is Lecturer in Religion at Aizwal Theological College, Mizoram. 94 THE TEACHINGS OF THE PR;'.JAPITA BRAHMA KUMARIS MOVEMENT In 1992 the Movement had over 3000 centres and sub-centres throughout the world in over 6 60 countries. -

The Brahma Kumaris World Spiritual University

IIAS Newsletter 47 | Spring 2008 | free of charge | published by IIAS | P.O. Box 9515 | 2300 RA Leiden | The Netherlands | T +31-71-527 2227 | F +31-71-527 4162 | [email protected] | www.iias.nl Photo ‘Blue Buddha’ by Lungstruck. Courtesy www.flickr.com 47 New Religious Movements The Brahma Kumaris World Spiritual University The Indian-based BKWSU arose from a Hindu cultural base, but tors are all ethnic Indian women although they have long been resident overseas. distinct from Hinduism. It began in the 1930s as a small spiritual National coordinators may be ethnic Indian, local members, or third country community called Om Mandli (Sacred Circle), consisting primarily of nationals, and some are males. In this sense the BKWSU closely resembles a young women from the Bhai Bund community of Hyderabad Sindh, multinational corporation (MNC) in tend- ing to have home country nationals posted now part of Pakistan. Since the 1960s the community has been known to key management roles overseas, with a degree of localisation at the host country as the Brahma Kumaris World Spiritual University (BKWSU), translated level. The use of third country nationals, or members from one overseas branch from the Hindi, ‘Brahma Kumaris Ishwariya Vishwa Vidyalaya’. It is posted to lead another overseas branch, attests to the strength of its organisational significant that the movement included a ‘world’ focus in its name, culture and the strength of shared values of its members. even though active overseas expansion did not begin until 1971. BKWSU is an international non–govern- mental organisation (NGO) that holds Tamasin Ramsay and Wendy Smith dle East), the US (America and Carib- general consultative status with the Eco- bean Islands), Russia (Eastern Europe) nomic and Social Council (ECOSOC) of the he BKWSU headquarters in Mt. -

Curriculum for Post Graduate Diploma in Yoga Education

Curriculum for Post Graduate Diploma in Yoga Education Ramakrishna Mission Sikshanamandira (An Autonomous Post-Graduate College under the University of Calcutta) College of Teacher Education (NCTE) Belur Math, Howrah- 711 202 West Bengal Page 2 of 16 Semester – I Course Title of the course Credits Hours Marks code PGDYE Historical Development and Traditional 4 4×15 = 60 100 101 Yoga PGDYE Yoga and Mental Health 4 4×15 = 60 100 102 PGDYE 100 103 Culture Synthesis and Value Education 4 4×15 = 60 Practicum PGDYE 104 Asanas, Pranayamas, Bandhas and their 8 8×15 = 120 100 techniques Total (1st Semester) 20 300 400 Semester – II Course Title of the course Credits Hours Marks code PGDYE Anatomy and Physiology of Yogic 4 4×15 = 60 100 105 Practices PGDYE Yoga Therapy 2 2×15 = 30 50 106 PGDYE Teaching Methodology 2 2×15 = 30 50 107 Practicum PGDYE Mudras and Kriyas, 6×15=90 108 Recitations and Medititions 6 100 Project Work PGDYE Project on Yoga Education 4 4×15 =60 50 109 Internship PGDYE Internship 2 2×15= 30 50 110 Total (2nd Semester) 20 300 400 Grand Total Credits, Hours and Marks (1st 40 40×15 = 600 800 Semester and 2nd Semester) Page 3 of 16 SEMESTER-I Paper- I: Historical Development and Tradition of Yoga (Course Code: PGDYE 101) Total Credits : 4 Full Marks : 100 (Each Credit : 15 hours) Assignment : 20 Marks Examination Duration : 3 hours Theory : 80 Marks Objectives: At the end of this course the students will be able to: Development of understanding on the concept and misunderstanding of Yoga. -

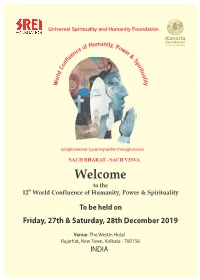

WC Booklet 2019 New Email.Cdr

Universal Spirituality and Humanity Foundation Enlightenment:ajourneywithinthroughservice SACH BHARAT - SACH VISVA Welcome to the 12th World Confluence of Humanity, Power & Spirituality To be held on Friday, 27th & Saturday, 28th December 2019 Venue: The Westin Hotel Rajarhat, New Town, Kolkata - 700156 INDIA Mission Ÿ To live and let live in peace, harmony, love - following the path of righteousness protecting Mother Earth. Ÿ Having faith in own religion while respecting other religions. Ÿ Awakening the inner power & ignite human power. Vision Ÿ A world with happiness, peace, harmony, austerity, simplicity, prosperity & good health for all. Ÿ Trinity of Power (money, authority, muscles) to be imbibed with Humanity & Spirituality. Ÿ Economic growth in synchronization with human facet. Ÿ Awakening woman power - reflecting God's love. Background: The World Confluence of Humanity, Power and Spirituality is being held every year with great success since 2010. So far 11 confluences were held, 6th-10th January, 2010, 2nd-4th January, 2011, 22nd-23rd December, 2012, 2nd-4th January, 2012, 28th-29th December, 2013, 27th-28th December, 2014, in Kolkata, 22nd-23rd December, 2015, in New Delhi, 7th May, 2016, in Mumbai, 16th-17th December, 2016, in New Delhi, 22nd-23rd December, 2017 and 21st-22nd December, 2018 in Kolkata. This programme is the first of its kind in the world with a conglomeration of important issues on humanity, power (inner & outer) and spirituality. Several distinguished luminaries whose hearts echo the humanity from different communities and religions across the world, shared their views that every religion propagates service to humanity, and that moral and social principles have its own paths leading to one cosmic reality. -

Religous Movements: Cult and Anticult Since Jonestown

Ann. Rev. Sociol. 1986. 12:329-46 Copyright K 1986 by Annual Reviews Inc. All rights reserved RELIGIOUS MOVEMENTS: CULT AND ANTICULT SINCE JONESTOWN Eileen Barker Dean of Undergraduate Studies, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE, England Abstract The article contains an overview of theoretical and empirical work carried out by sociologists of religion in the study of new religious movements and the anticult movement since 1978; it pays special attention to the aftereffects of the mass suicide/murder of followers of Jim Jones in Guyana. The different theories as to why people join the movement are discussed-whether they are 'brainwashed,' what influences (pushes and/or pulls) the wider society has on the membership. Mention is made of the role of sociologists themselves as witnesses in court cases and as participant observers at conferences organized by the movements. Bibliographic details are supplied of writings about particu- lar movements, in particular countries, and concerning particular problems (finances, family life, legal issues, conversion, 'deprogramming,' etc) It is suggested that the differences between the movements are considerably greater than is often recognized and that there is a need for further comparative research and more refined classificatory systems before our theoretical knowledge can develop and be tested satisfactorily. Various changes (such as the demographic variables of an aging membership, the death of charismatic leaders, and the socialization of second-generation membership; changing relationships with the 'host' society; and the growth-or demise-of the movements) provide much more of interest for the sociologist to study in the future. -

Historical Timeline of Hinduism in America 1780'S Trade Between

3/3/16, 11:23 AM Historical Timeline of Hinduism in America 1780's Trade between India and America. Trade started between India and America in the late 1700's. In 1784, a ship called "United States" arrived in Pondicherry. Its captain was Elias Hasket Derby of Salem. In the decades that followed Indian goods became available in Salem, Boston and Providence. A handful of Indian servant boys, perhaps the first Asian Indian residents, could be found in these towns, brought home by the sea captains.[1] 1801 First writings on Hinduism In 1801, New England writer Hannah Adams published A View of Religions, with a chapter discussing Hinduism. Joseph Priestly, founder of English Utilitarianism and isolater of oxygen, emigrated to America and published A Comparison of the Institutions of Moses with those of the Hindoos and other Ancient Nations in 1804. 1810-20 Unitarian interest in Hindu reform movements The American Unitarians became interested in Indian thought through the work of Hindu reformer Rammohun Roy (1772-1833) in India. Roy founded the Brahmo Samaj which tried to reform Hinduism by affirming monotheism and rejecting idolotry. The Brahmo Samaj with its universalist ideas became closely allied to the Unitarians in England and America. 1820-40 Emerson's discovery of India Ralph Waldo Emerson discovered Indian thought as an undergraduate at Harvard, in part through the Unitarian connection with Rammohun Roy. He wrote his poem "Indian Superstition" for the Harvard College Exhibition of April 24, 1821. In the 1830's, Emerson had copies of the Rig-Veda, the Upanishads, the Laws of Manu, the Bhagavata Purana, and his favorite Indian text the Bhagavad-Gita. -

Bagwan Cult at Center of Peace Movement's Merger with the 'Spiritual Unity' Gurus

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 11, Number 5, February 7, 1984 Bagwan cult at center of peace movement's merger with the 'spiritual unity' gurus by Martha Quinde and Ira Liebowitz With help from the United Nations, the "world spirituality " exceeding 4 billion people. Aquarian Age cults are in the process of merging with the Robert Muller, in addition to his U.N. and Lucis posts, international disarmamentmovement. How this has occurred is also an official of the Brahma Kumaris University and a was indicated at a "Universal Peace Conference " held a year close associate of former Carter administration drug-policy ago at Mount Abu in India. counselor Peter Bourne, the official exposed as peddling Under the sponsorship of the Brahma Kumaris World illicit prescriptions who was recently involved in the aborted Spirituality University, the conference pledged to "enter the communist takeover of the island of Grenada. Muller de age of love "-based on consolidating ties between the peace scribes Brahma Kumaris as a "spirituality project " set up by movement, terrorist front groups, and religious cults pro his Buddhist mentor U Thant-the longtime U.N. secretary grammed to support disarmament from a "world spirituality " general-through the United Nations. Another project of standpoint. Muller's, born at the Mt. Abu conference, is a "World Uni Among. the speakers at the February 1983 conference versity for Peace " in Costa Rica. Under the auspices of Brah were Willis Harman of the Stanford Research Institute, an rna Kumaris, former Costa Rican president Rodrigo Carazo advocate of obliterating technological progress, heterosex was recently in West Germany meeting with various "peace " uality, and Western civilization overall; and Robert Muller, institutes to develop a curriculum for the university. -

Using Communications Theory to Explore Emergent Organisation in Pagan Culture*

ARSR 24.2 (2011): 150-174 ARSR (print) ISSN 1031-2943 doi: 10.1558/arsr.v24i2.150 ARSR (online) ISSN 1744-9014 Using Communications Theory to Explore Emergent Organisation in Pagan Culture* Angela Coco* Southern Cross University Abstract Pagan culture presents a paradoxical case to the traditional frameworks and methodologies social scientists have used to describe religious organi- sation. A key factor influencing Paganism’s emergence has been its adop- tion of online communications. Such communications provide a means of coordinating activities in and between networks accommodating diverse beliefs and practices and the ability to avoid overarching hierarchical organisation. These characteristics have led theorists to label Paganism as a postmodern religion, signalling the possibility of a different kind of social organisation from that evidenced in modern religions. Karaflogka (2003) distinguishes between two aspects of the move online, religion in cyberspace and religion on the Internet. While the Internet may be an online place for cybercovens and for performing cyber rituals, the analysis in this paper focuses on the interweaving of online and offline communic- ative practices. I suggest that communications theories, as outlined in Wenger’s ‘communities of practice’ model (1998) and Taylor and Van Every’s (2000) communications mapping, afford frameworks for exploring the inter-connectedness of online/offline interactions and a means of identifying emergent organisation in the Pagan movement. The analysis focuses on a particular feature of Pagan organisation, the accommodation of both group-oriented and solitary pagans. Keywords Pagan, communication theory, information and communication technologies, Pagan organisation, postmodern religion * I would like to offer my thanks to the anonymous reviewers of this paper whose constructive suggestions motivated considerable improvements. -

Brahma Kumaris Sahaj Raj-Yoga Meditation

J. Adv. Res. in Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Sidhha & Homeopathy Volume 6, Issue 1&2 - 2019, Pg. No. 1-9 Peer Reviewed & Open Access Journal Review Article Brahma Kumaris Sahaj Raj-Yoga Meditation - As a Tool to Manage Various Levels of Stress Siddappa Naragatti1, NK Hiregoudar2 1Yoga Therapist, Central Council for Research in Yoga Naturopathy, New Delhi, India. 2Ojashvi Yoga Training School Rishikesh, Uttarakhand, India. DOI: https://doi.org/10.24321/2394.6547.201901 INFO ABSTRACT Corresponding Author: Brahma Kumaris Sahaj Raja Yoga Meditation is an ancient technique Siddappa Naragatti, Central Council for Research to bring the mental peace and inner harmony. The research on the in Yoga Naturopathy, New Delhi, India. practices of such techniques has shown that, they are great help in the E-mail Id: stress management and in the prevention of many of the psychosomatic [email protected] diseases. Orcid Id: The word “Yoga” simply means “Union” and the word “Raja” means https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8644-4160 “Supreme”, “King” or “Master”. Raja Yoga is the king of all yoga because How to cite this article: through it one can become sovereign. Naragatti S, Hiregoudar NK. Brahma Kumaris Sahaj Raj-Yoga Meditation - As a Tool to Manage The regular practice results in good health, happiness and prosperity in Various Levels of Stress. J Adv Res Ayur Yoga life. This review article focuses on the beneficial effects of BarhmaKumaris Unani Sidd Homeo 2019; 6(1&2): 1-9. Sahaj Raja Yoga Meditation through the effective stress management mechanisms. Date of Submission: 2019-03-10 Date of Acceptance: 2019-06-12 Purpose of the Research: Main aim in doing this is to build healthy, wealthy happy, and value based society. -

From Brahma Kumari Academy to Ramakrishna Mission

From Brahma Kumari Academy to Ramakrishna Mission Documents on Government of India Sponsorship of Ramakrishna Mission Value Education Programmes: 2010 onwards (Suman Gupta) 1. Indian Express articles, June 2010 Brahma Kumaris to take value education classes in Kendriya Vidyalayas Anubhuti Vishnoi Posted online: Wed Jun 09 2010, 00:33 hrs http://archive.indianexpress.com/news/brahma-kumaris-to-take-value-education-classes-in-kendriya- vidyalayas/631273/ New Delhi : There is no dispute over inclusion of value education in school curriculum but when that is outsourced to a religious or spiritual organisation, it is bound to raise eyebrows. The Central government-run Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangathan (KVS), which presides over a chain of thousand-plus schools, has done just that by directing all its schools to allow the nearest Brahma Kumari Academy to hold a weekly class on Peace Education. In a letter to all its regional offices, the KVS has said each school must contact the nearest Brahma Kumari Academy so that “representative can take one period in a week in classes VII, VIII & IX in KVs free of cost”. Kendriya Vidyalayas across the country have quickly followed the directive, touching base with the nearest Brahma Kumari centre. The Brahma Kumaris too have lost no time in contacting the nearest KVs. The Brahma Kumari organisation describes itself as a socio-spiritual and educational institution of international repute with over 8,000 centres in 132 countries and committed to the cause of moral and spiritual uplift of mankind. The KVS maintains that they have tied up with the Brahma Kumaris for value education lessons and also ensured that the content on offer is going to be “completely secular”.