Review “African [Women] A-Liberate Zimbabwe”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

ASSATA ZERAI, Ph.D. Professor, Department of Sociology, Associate Chancellor for Diversity; University of Illinois 3102 Lincoln Hall MC-454, 702 South Wright Street, Urbana, Illinois 61801 | 217-333-7119 [email protected] EDUCATION University of Chicago Ph.D. in Sociology Dissertation: Preventive Health Strategies and Child Survival in Zimbabwe 1993 University of Chicago M.A. in Sociology 1988 Anderson University B.A. in Sociology 1986 EMPLOYMENT University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Associate Chancellor for Diversity 2016-present University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Professor of Sociology 2016-present University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Affiliate, Women and Gender Studies 2016-present University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Director, Core Faculty, Center for African Studies 2015-16 University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Associate Dean, Graduate College 2014-2016 University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Associate Professor of Sociology 2002-2016 University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Director of Graduate Studies for Department of Sociology 2007-2012 University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Core Faculty, Center for African Studies 2009-2016 ASSATA ZERAI, PH.D. PAGE 2 University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Associate Professor, African American Studies and Research 2002-2006 National Development and Research Institutes, New York, NY Research Fellow 2003-2005 Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY Associate Professor, Department of Sociology 2002 Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology -

The Impact of Walter Rodney and Progressive Scholars on the Dar Es

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Tile IIBPact ofW .......... y .ad Progressive SeII.lln .. tile Dar es S..... SdIooI Horace Campbell Utqfiti Vol VIII No.2. 1986. Journal SmIOT lActurer. of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University ol/Jar es $4Itwn University of Oar es Salaam The University of Oar es Salaam in Tanzania faces the same problem of the contradictory nature of University education which is to be found in all States of Africa. Discontinuities between the pre-colonial, colonial and post~ 9Ol0nial patterns and methods of education continue as the present components of formal education strive to retain relevance to the needs of the society. The interconnections between education and various aspects of the life of the socie- ty.remain problematic in so far as the structures, content and language of hi&her education in Tanzania and indeed the rest of Africa remain geared to the train- ing of high level manpower. This requirement of skilled manpower meets the needs of the administration of the people but the needs of the producers are not immediately met by the University. Throughout the African continent, the educational needs of the vast majority of the toilers are met by the transmis- sion of skills and agricultural knowledge accumulated over centuries and con- veyed through practical experience rather than in a classroom. -

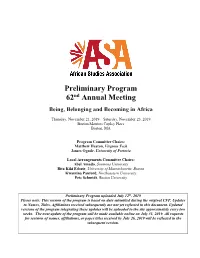

Preliminary Program Full V3.0

Preliminary Program nd 62 Annual Meeting Being, Belonging and Becoming in Africa Thursday, November 21, 2019 – Saturday, November 23, 2019 Boston Marriott Copley Place Boston, MA Program Committee Chairs: Matthew Heaton, Virginia Tech James Ogude, University of Pretoria Local Arrangements Committee Chairs: Abel Amado, Simmons University Rita Kiki Edozie, University of Massachusetts, Boston Kwamina Panford, Northeastern University Eric Schmidt, Boston University Preliminary Program uploaded July 12th, 2019 Please note: This version of the program is based on data submitted during the original CFP. Updates to Names, Titles, Affiliations received subsequently are not yet reflected in this document. Updated versions of the program integrating these updates will be uploaded to the site approximately every two weeks. The next update of the program will be made available online on July 31, 2019. All requests for revision of names, affiliations, or paper titles received by July 26, 2019 will be reflected in the subsequent version. Program Theme The theme of this year’s Annual Meeting is “Being, Belonging and Becoming in Africa.” While Africa is not and never has been homogenous or unitary, the existence of the ASA is predicated on the idea that there are things that distinguish “Africa” and “Africans” from other peoples and places in the world, and that those distinctions are worth studying. In a world increasingly preoccupied with tensions over localism, nationalism, and globalism, in which so many forms of essentialism are under existential attack (and fighting back), we hope that this theme will spark scholarly reflection on what it has meant and currently means for people, places, resources, ideas, knowledge, among others to be considered distinctly “African.” As scholars have grappled with the conceptual and material effects of globalization, the various disciplines of African Studies have also embraced transnational, international, and comparative approaches in recent decades. -

Professor Horace Campbell: University of Ghana Kwame Nkrumah Chair in African Studies Installed

Professor Horace Campbell: University of Ghana Kwame Nkrumah Chair in African Studies Installed Horace Campbell (third person, in white shirt) and members of the University of Ghana faculty and administration). The third occupant of the Kwame Nkrumah Chair in African Studies, Professor Horace Campbell, has been officially installed at a colorful ceremony on Tuesday, 7 February 2017, at the Great Hall. After the installation, Professor Campbell delivered an inaugural lecture titled “Reconstruction, Transformation and the Unification of the Peoples of Africa in the 21st Century: Rekindling the Pan African Spirit of Kwame Nkrumah.” The lecture was underpinned by insights of Nkrumah concerning the building of a unified and secure Africa as a foundation for ensuring the true liberation of the continent. Professor Campbell used his lecture to outline his research agenda as occupant of the Chair. He made a commitment to deepening the work of his predecessors to amplify the messages about Kwame Nkrumah, Pan Africanism and freedom. 220 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.10, no.5, July 2017 He emphasized the unification of African peoples, and presented the Agenda 2063 of the African Union as a home-grown pathway to ensure the integration and prosperity in an African continent governed by its own people and using its own resources for its own transformation. “We need unified economic planning for Africa. Until the economic power of Africa is in our hands, the masses can have no real concern and no real interest for safeguarding our security, for ensuring the stability of our regimes, and for bending their strength to the fulfilment of our ends”, he stated. -

China's Influence in Africa: Current Roles

CHINA’S INFLUENCE IN AFRICA: CURRENT ROLES AND FUTURE PROSPECTS IN RESOURCE EXTRACTION Liu Haifang* ABSTRACT In the second half of 2014, some African countries felt the heavy strike of falling prices of mineral resources on the world market. The international media raised vocalex positions on the negative impact that China’s slow down might bring to the African economy. One headline read: “Chinese investment in Africa has fallen 40 per cent this year – but it’s not all bad news”.1 More recently, the exasperation intensified to “China’s slowdown blights African economies”,2 and managed to shadow the China-African Summit held in December 2015 in Johannesburg. Similarly, on the recent Africa Mining Indaba, the annual biggest African event for the mining sector, the renewed concern was stated as “Gloom hangs over African mining as China growth slows”.3 There is no doubt that China’s presence has had positive effects on Africa’s growth over the past decade. Nonetheless, only a narrow perspective would view Africa’s weak performance solely through the Chinese prism. This article addresses the afore-mentioned concerns regarding the impacts that China has in Africa. A historical approach is applied to reconstruct * PhD (Peking), Associate Professor, Deputy Director and Secretary General of the Centre for African Studies, School of International Studies, Peking University, China. Email: [email protected] 1 Quartz Africa Weekly Africa, “Chinese investment in Africa has fallen 40% this year—but it’s not all bad news”, 18 November 2015, available online at <http:/ /finance.yahoo.com/news/chinese-investment-africa-fallen-40-060057915. -

For African Studies Association Members

. i l. FOR AFRICAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION MEMBERS VOLlIMEXX JUL V/SEPTEMBER 1987 NO.3 \. TABLE OF CONTENTS ASA Board of Directors 2 Notes from the Secretariat 2 1987 ASA Annual Meeting 3 1988 ASA Annual Meeting Call for Papers 4 Bids for Editorship of African Studies Review 4 ASA Elections 5 Obituary: Chief Obafemi Owolowo, 1909-1987 6 Special Announcements 7 Grants & Awards 8 Meetings-Past & Future 9 Employment 11 Publications Received 14 L~ Recent Doctoral Dissertations 19 .' Special Insert: 1987 Annual Meeting Preliminary Program - 2 ASA BOARD OF DIRECTORS OFFICERS President: Aidan Southall, University of Wisconsin-Madison (Exec. Comm.) Vice-president: Nzongola-Nta1aja, Howard University (Nom. Comm.) Past-president: Gerald J. Bender, Univ. of Southern California (publ. Comm.) RETIRING IN 1987 Edna G. Bay, Emory University (Exec. Finance & Devel. Comm.) Abena P.A. Busia, Rutgers University (Nom. Comm.) Mark DeLancey, Univ. of South Carolina (Publ. & Devel. Comm.) RETIRING IN 1988 Edward A. Alpers, Univ. of Calif., Los Angeles (Exec. & Devel. Comm.) M. Jean Hay, Boston University (Publ. & Finance Comm.) Joseph C. Miller, Univ. of Virginia (Nom., Finance & Devel. Comm.) RETIRING IN 1989 Mario J. Azevedo, Univ. of No. Carolina, Charlotte (Fin. Comm.) Pauline H. Baker, Carnegie Endowment for Int'l Peace (Nom. & Exec. Comm.) Allen F. lsaacman, Univ. of Minnesota (Publ. Comm.) NOTES FROM THE SECRETARIAT As the last issue of the News was quite substantial, we do not have as much material to place in the summer issue. We have, however, placed an updated preliminary Meeting Program within, please use this latest as your guide, as there are some changes from that which was mailed in the preregistration packets. -

The African E-Journals Project Has Digitized Full Text of Articles of Eleven Social Science and Humanities Journals

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Pan African Renewal in The 21st Century HORACE CAMPBELL The thrust of this contribution is to reflect on how the spirit of redemption and emancipation can be harnessed to make a decisive impact on humanity in the 21st century. The victories of the African peoples in rolling back the frontiers of colonial domination must be tempered by the realities of the conditions of the African at home and abroad. The elections and transition process in South Africa encapsulates the strengths and weaknesses of the liberation process this century. It is the changed political conditions for the African in the context of reorganised imperialism that the question of liberation needs to be reconceptualised. In the call for the Seventh Pan African Congress which was held in Uganda, the International Preparatory Committee had hoped to maintain the old spirit of the broad nature of the Pan African movement of the past century. The meeting, the third of its kind to be held since the All African Peoples Conference in 1957, was open to all shades of opinion, groups and individuals in the Pan African world. The broad theme of " Pan Africanism: Facing the Future in Unity, Social Progress and Democracy" failed to find ways to harmonise the direction of this 7th Pan African Congress with the Congresses which are going on in the streets, valleys, villages and communities all across the Pan African World. -

Since the BRICS Are Dying, Pan-Africanism Must Be Rebuilt from Below

Since the BRICS are dying, Pan-Africanism must be rebuilt from below By Patrick Bond1 Professor of Political Economy, University of the Witwatersrand School of Governance and Director of the Centre for Civil Society, University of KwaZulu-Natal presented to the Workshop on Decolonising International Relations in the Time of Crisis: World Order Visions and Practices from the Global South Panel 4: “Pan Africanism is Dead, Long Live the BRICS!” University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 15 March 2016 ABSTRACT: To address whether the Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa (BRICS) bloc contributes to decolonising (as opposed to recolonising) world order visions, this presentation will cover three papers currently in the publication process, with an agenda of provoking consideration of three central questions: are the BRICS anti-imperial or sub-imperial?; will the BRICS New Development Bank mitigate or amplify financial imperialism?; and with the end of the Africa Rising hype, what potential is there for an African Uprising against adverse consequences of the BRICS’ ‘New Scramble for Africa’ agenda? (My answers: sub-imperial, amplify, and enormous.) Introduction: Anti-or sub-imperial BRICS? First, is there a coherent theoretical approach capable of incorporating into contemporary political economy the Brazil-Russia-India-South Africa (BRICS) countries’ alliance? A more explicitly theoretical strategy is needed to contend with two kinds of normativities associated with the new industry of BRICS ‘think tank’ cooperation, donor interest and researcher opportunism on the one hand, and on the other with romanticism displayed by radical Third Worldist analysts. The pages below argue for an interpretation of BRICS not typically comprehensible within the mainstream of analysis: ‘subimperialism,’ based on locating the BRICS within global uneven and combined development. -

CLASS STRUGGLE HEIGHTENS in KENYA by Horace Campbell in The

CLASS STRUGGLE HEIGHTENS IN KENYA By Horace Campbell In the latest novel of Ngugi Wa Thiong'o, the Kenyan writer, the setting is a feast of thieves who compare notes and vie with one another in boasting how they became rich. The novel -- T.he Devil on the Cross -- exposes the celebration of corruption by the Kenyan leadership who have made Kenya the epicentre of imper ialist operations in Eastern and Central Africa. The procession of workers, small farmers and students who disrupt the feast is a vivid portrayal of the power of organised working class action. But as yet, the working poor in Kenya have not been organised in their own independent movement . So, despite flashes of militant action, reported struggles in Kenya are those of the intra-class squabbles between different sections of the ruling clique who have had to increase social and political repression in order to remain in power. Soweto Equivalent On August 1, 1982, the myth of the stable, prosperous Kenya was cracked when the reality of repression and intra-class squab bles erupted in the form of an attempted coup d'etat. This at tempted coup which was an expression of the level of force in Kenyan politics, left more than one thousand Kenyans dead, and subsequently led to the burning out of fifteen thousand workers from their homes in Mathere Valley, one of the most notorious pools of reserve labour north of Soweto. The squabbles in Kenya reverberated in Washington, as the Pentagon feared that a change of regime would affect the future of one of the most important American naval bases in the Indian Ocean, at Nombasa. -

A Journal of African Studies

UCLA Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies Title Front Matter Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9q13s4jk Journal Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 14(2) ISSN 0041-5715 Author n/a, n/a Publication Date 1985 DOI 10.5070/F7142017040 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California OFAHAMU Editor-in-chief: Fassil De.missie Book Review Editor: Robin D.G. Kelley Production Editor: Doris Johnson-Ivanga Editorial Board: Ali Jimale Ahmed, Ziba Bonginkosi Jiyane, Robin D. G. Kelley, Peter Ngau, Christiana Oboh, P. Godfrey Okoth, Segun Oyekunle. Advisor: Teshome H. Gabriel Cover Design: M. Quant Former Editors: J. Ndukaku Amankulor, ! . N.C. Aniebo, Louis D. Armmand, Kandioura Drame, Teshome H. Gabriel, Kyalo Mativo, Niko M. Ngwenyama, Edward c. Okwu, Renee Poussaint, Kipkorir Aly Rana, Nancy Rutledge. CONTRIBUTIONS UFAHAMO will accept contributions from anyone interested in Africa and related subject areas. Contributions may include scholarly articles, political-economic analyses, commentaries, film and book reviews and freelance prose, art work and poetry. Manuscripts may be of any length, but those of 15-25 pages are preferred. (All manuscripts must be clearly typed, double-spaced originals with footnotes gathered at the end. Contributors should endeavor to keep duplicate copies of all their manuscripts.) The Editorial Board reserves the right to edit any manuscript to meet the objectives of the journal. Authors should send with article a brief biographical note, indicating position, academic affiliation and recent publications, etc. All correspondence -- manuscripts, subscriptions, books for review, inqu1.r1.es, etc. , -- should be addressed to the Editor-in-Chief at the following address: AFRICAN ACTIVIST ASSOCIATION AFRICAN STUDIES CENTER UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90024 UFARAMU Volume XIV, Number 2, 1985 Contents Contributors . -

Uneven Citizen Advocacy Within the BRICS, Within Global Governance

Uneven citizen advocacy within the BRICS, within global governance Patrick Bond (Distinguished Professor of Political Economy, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg) 1. Please share your experience in exercising, or seeking to exercise, your right to participate in public affairs in one or several of the following global governance groupings/spaces: G7, G20, G77/G24, NAM, BRICS, WEF and BM in terms of: Access; Inclusivity; and Influencing the decision-making process. The BRICS are a fascinating case of multilateral collaboration because their claims to transparency and - starting in 2015 - civil society participation in annual summit processes are ambitious. However, the individual regimes - especially China, Russia and increasingly also India and Brazil - are authoritarian, and Chinese surveillance of the citizenry verges on totalitarianism, while violence against democracy and social-justice activists is experienced in all five BRICS, often at high levels (although not yet in the context of activism critical of the BRICS per se). The worst current case is certainly Brazil, where state repression is far greater than at any time since democracy was regained in 1985; Jair Bolsonaro will host the BRICS heads of state summit in Brasilia in November. In this context, it is now apparent that in order for the BRICS leaders to claim that they aim to democratise the international order - such as was heard at the 2018 G20 Buenos Aires summit when the five leaders briefly met separately - it is also useful for them to engage a layer of civil society, labour, youth, women and academics, albeit in generally uncritical, sanitised formats. This allows for 'civilised society' access - e.g. -

Freedom Dreams

Freedom Dreams . “A powerful book....Robin D. G. Kelley produces histories of black rad- icalism and visions of the future that defy convention and expectation.” — . ove and imagination may be the in the imaginative mindscapes of Lmost revolutionary impulses Surrealism, in the transformative po- available to us, and yet we have tential of radical feminism, and in the failed to understand their political four-hundred-year-old dream of importance and respect them as reparations for slavery and Jim powerful social forces. Crow. This history of renegade intellec- With Freedom Dreams, Kelley af- tuals and artists of the African dias- firms his place as “a major new voice pora throughout the twentieth cen- on the intellectual left” (Frances Fox tury begins with the premise that the Piven) and shows us that any serious catalyst for political engagement has movement toward freedom must be- never been misery, poverty, or op- gin in the mind. pression. People are drawn to social movement because of hope: their Robin D. G. Kelley, a frequent con- dreams of a new world radically dif- tributor to the New York Times, is ferent from the one they inherited. professor of history and Africana From Aimé Césaire to Paul Robe- studies at New York University and son to Jayne Cortez, Kelley unearths author of the award-winning Ham- freedom dreams in Africa and Third mer and Hoe, Race Rebels, and Yo’ World liberation movements, in the Mama’s Disfunktional! He lives in hope that Communism had to offer, New York City. When History Sleeps: A Beginning i FREEDOM DREAMS ii Freedom Dreams Other works by Robin D.