WALTER RODNEY--PEOPLES' HISTORIAN by Horace Campbell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Continuing Relevance of Walter Rodney

CODESRIA Bulletin, No. 1, 2021 Page 15 Remembering Walter Rodney The Continuing Relevance of Walter Rodney In Memory of Prof. Ian Taylor rofessor Ian Taylor’s article on the “Continuing Relevance of Walter Rodney” is published posthumously. Prof. Taylor Psubmitted the article for publication in Africa Development on November 30th 2020. Though the peer review com- ments were shared with him, CODESRIA did not receive any response nor a revised version of the article. The silence seemed unusual, since Ian had a previous record of engagement with CODESRIA. His last publication with CODESRIA was an article published in Africa Development, Vol. XLII, No. 3, 2017 on “The Liberal Peace Security Regimen: A Gramscian Critique of its Application in Africa”. His failure to respond to the peer review comments was therefore a cause of concern and the sad news of his illness, hospitalisation and eventual passing on February 22nd 2021 explained it all. Ian Taylor’s work hoovered in African studies in a way that colleagues and students admired and will continue to appreciate. In his email submitting this article on Walter Rodney for publication, he pointed out his strong believe in Walter Rodney’s political methodology and Africa-centred epistemology which he noted will continue to have relevance in any study of Africa. Ian was unapologetically radical in his academic pursuits and his engagement was tied to the activism that informed this radicalism. With wide ranging interest in Africa, especially in Botswana where he taught at the University of Botswana for a while, Ian’s interest started and expanded to other regions of the world without abandoning the African connection. -

WALTER RODNEY on PAN-AFRICANISM* by Robert A

WALTER RODNEY ON PAN-AFRICANISM* By Robert A. Hill [And]yet ' tis clear that few men can be so lucky as to die for a cause, without first of all having lived for it. And as this is the most that can be asked from the greatest man that follows a cause, so it is the least that can be taken from the smallest. William Morris, The Beauty of Life (1880)1 Discovery creates the unity (and] unity is created in struggle and is so much more valid because it is created in struggle. Walter Rodney (1974)2 The stimulus that ign·ited the moaern Pan-African conscious ness, both in Africa and the African diaspora in the West, was Ghana's attainment of political independence in 1957. Fanned by the winds of decolonization that swept the African continent in its aftermath, Pan-Africanism reemerged as the major ideological expression of African freedom. The nexus of black struggle was also enlarged significantly at the same time as the black freedom movement in the United States deepened and developed . When Malcolm X underlined the importance to black struggle everywhere of Africa's strategic position on the world scene, he was build ing on the consciousness that was the result of a decade and a half of struggle. There were profound reverberations from this renewal of Pan- African consciousness which were felt in the Caribbean, re awakening not only a sense of racial pride in Africa but also, more importantly, an awareness of the potential for transforma tion within the Caribbean region. -

Bob Brown on Ideologies

BOB BROWN ON IDEOLOGIES From his Facebook Timeline December 27 – 30, 2014 Compiled By Lang T. K. A. Nubuor BOB BROWN ON IDEOLOGIES (From his Facebook Timeline) This is the full update of the discourse on Comrade Bob Brown’s timeline as the time of this update. In our previous publication we undertake minimal editing to correct obvious typographical errors. It appears that that does not go down well with Comrade Brown. For that reason, in this update we maintain the discourse in its pristine state. Secondly, we take notice of Comrade Brown’s objection that our publication infringes on his intellectual property rights (See below). We explain that our action is inspired by the need to comprehensively inform readers on our timeline on the discourse. Since we are not tagged in the original post the subsequent reactions do not appear there. We think that by merely ‘sharing’ Comrade Brown’s post (which ‘sharing’ is a legal act on Facebook timelines) we deny our readers – especially those who are not on his timeline – the opportunity to read those reactions. Hence, we send a message to him to tag our timeline to enable our access to the full discourse. He receives it without a reply. As such, we are compelled to render the discourse in this PDF form while directing our readers to it on our blog, that is, www.consciencism.wordpress.com. It is our hope that given his decades of experience in the historical Pan-African struggle he allows this free spread of his ideas and reactions to them by any non-commercial means such as ours. -

Walter Rodney and Black Power: Jamaican Intelligence and Us Diplomacy*

ISSN 1554-3897 AFRICAN JOURNAL OF CRIMINOLOGY & JUSTICE STUDIES: AJCJS; Volume 1, No. 2, November 2005 WALTER RODNEY AND BLACK POWER: JAMAICAN INTELLIGENCE AND US DIPLOMACY* Michael O. West Binghamton University On October 15, 1968 the government of Jamaica barred Walter Rodney from returning to the island. A lecturer at the Jamaica (Mona) campus of the University of the West Indies (UWI), Rodney had been out of the country attending a black power conference in Canada. The Guyanese-born Rodney was no stranger to Jamaica: he had graduated from UWI in 1963, returning there as a member of the faculty at the beginning of 1968, after doing graduate studies in England and working briefly in Tanzania. Rodney’s second stint in Jamaica lasted all of nine months, but it was a tumultuous and amazing nine months. It is a measure of the mark he made, within and without the university, that the decision to ban him sparked major disturbances, culminating in a rising in the capital city of Kingston. Official US documents, until now untapped, shed new light on the “Rodney affair,” as the event was soon dubbed. These novel sources reveal, in detail, the surveillance of Rodney and his activities by the Jamaican intelligence services, not just in the months before he was banned but also while he was a student at UWI. The US evidence also sheds light on the inner workings of the Jamaican government and why it acted against Rodney at the particular time that it did. Lastly, the documents offer a window onto US efforts to track black power in Jamaica (and elsewhere in WALTER RODNEY AND BLACK POWER: JAMAICAN INTELLIGENCE AND US DIPLOMACY Michael O. -

Abdias Nascimento E O Surgimento De Um Pan-Africanismo Contemporâneo Global Moore, Carlos Wedderburn

Abdias Nascimento e o surgimento de um pan-africanismo contemporâneo global Moore, Carlos Wedderburn Meu primeiro encontro com Abdias do Nascimento, amigo e companheiro intelectual há quatro décadas, aconteceu em Havana, em 1961, quando a revolução cubana ainda não havia completado três anos de existência. Eu tinha 19 anos, Abdias, 47. Para mim, esse encontro significou o descobrimento do mundo negro da América Latina. Para ele, essa visita a Cuba abria uma interrogação quanto aos métodos que se deveriam empregar para vencer quatro séculos de racismo surgido da escravidão. E se me atrevo a prefaciar este primeiro volume de suas Obras, é apenas porque no tempo dessa nossa longa e intensa amizade forjou-se uma parceria política na qual invariavelmente participamos de ações conjuntas no Caribe, na América do Norte e no Continente Africano. As duas obras aqui apresentadas tratam de eventos acontecidos no período de seu exílio político (1968-1981) e dos quais fui testemunha. É, portanto, a partir dessa posição de amigo, de companheiro intelectual e de testemunha que prefacio este volume, sabendo que deste modo assumo uma pesada responsabilidade crítica tanto para com os meus contemporâneos quanto em relação às gerações vindouras. Duas obras compõem este volume. O traço que as une é o fato de os acontecimentos narrados com precisão de jornalista em Sitiado em Lagos decorrerem diretamente das colocações políticas e da leitura sócio-histórica sobre a natureza da questão racial no Brasil que se encontram sintetizadas em O genocídio do negro brasileiro. Essas obras foram escritas da forma que caracteriza o discurso "nascimentista" - de modo direto, didático, e num tom forte, à maneira de um grito. -

THE TRAINING of an INTELLECTUAL, the MAKING of a MARXIST, by Richard Small

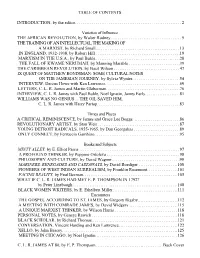

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION, by the editor. ........................................................2 Varieties of Influence THE AFRICAN REVOLUTION, by Walter Rodney. ......................................5 THE TRAINING OF AN INTELLECTUAL, THE MAKING OF A MARXIST, by Richard Small...............................................13 IN ENGLAND, 1932-1938, by Robert Hill ..............................................19 MARXISM IN THE U.S.A., by Paul Buhle................................................28 THE FALL OF KWAME NKRUMAH, by Manning Marable ............................39 THE CARIBBEAN REVOLUTION, by Basil Wilson.....................................47 IX QUEST OF MATTHEW BONDSMAN: SOME CULTURAL NOTES ON THE JAMESIAN JOURNEY, by Sylvia Wynter...........................54 INTERVIEW, Darcus Howe with Ken Lawrence. ........................................69 LETTERS, C. L. R. James and Martin Glaberman. .........................................76 INTERVIEW, C. L. R. James with Paul Buhle, Noel Ignatin, James Early. ...................81 WILLIAMS WAS NO GENIUS ... THE OIL SAVED HIM, C. L. R. James with Harry Partap. .83 Times and Places A CRITICAL REMINISCENCE, by James and Grace Lee Boggs. .........................86 REVOLUTIONARY ARTIST, by Stan Weir ............................................87 YOUNG DETROIT RADICALS, 1955-1965, by Dan Georgakas . .89 ONLY CONNECT, by Ferruccio Gambino................................................95 Books and Subjects MINTY ALLEY, by E. Elliot Parris ........................................................97 -

Curriculum Vitae

ASSATA ZERAI, Ph.D. Professor, Department of Sociology, Associate Chancellor for Diversity; University of Illinois 3102 Lincoln Hall MC-454, 702 South Wright Street, Urbana, Illinois 61801 | 217-333-7119 [email protected] EDUCATION University of Chicago Ph.D. in Sociology Dissertation: Preventive Health Strategies and Child Survival in Zimbabwe 1993 University of Chicago M.A. in Sociology 1988 Anderson University B.A. in Sociology 1986 EMPLOYMENT University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Associate Chancellor for Diversity 2016-present University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Professor of Sociology 2016-present University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Affiliate, Women and Gender Studies 2016-present University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Director, Core Faculty, Center for African Studies 2015-16 University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Associate Dean, Graduate College 2014-2016 University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Associate Professor of Sociology 2002-2016 University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Director of Graduate Studies for Department of Sociology 2007-2012 University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Core Faculty, Center for African Studies 2009-2016 ASSATA ZERAI, PH.D. PAGE 2 University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Associate Professor, African American Studies and Research 2002-2006 National Development and Research Institutes, New York, NY Research Fellow 2003-2005 Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY Associate Professor, Department of Sociology 2002 Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology -

Moving Against the System

THE marxedproject.org MOVING AGAINST THE SYSTEM THE 1968 CONGRESS OF BLACK WRITERS AND THE MAKING OF GLOBAL CONSCIOUSNESS with Author and Editor DAVID AUSTIN SUNDAY, JANUARY 27, 1:00 - 3:30 PM @The Peoples Forum, 320 West 37th Street, NYC In 1968, as protests shook France and war raged in Vietnam, the giants of Black radical politics descended on Montreal to discuss the unique challenges and struggles facing their Black brothers and sisters. For the first time since 1968, David Austin brings alive the speeches and debates of the most important international gathering of Black radicals of the era. Against a backdrop of widespread racism in the West, and colonialism and imperialism in the Third World, this group of activists, writers and political figures gathered to discuss the history and struggles of people of African descent and the meaning of Black Power. With never-before-seen texts from Stokely Carmichael, Walter Rodney and C.L.R. James, these documents will prove invaluable to anyone interested in Black radical thought, as well as capturing a crucial moment of the political activity around 1968. is the author of the CasaDAVID de lasAUSTIN Americas Prize-winning Fear of a Black Nation: Race, Sex, and Security in Sixties Montreal, Moving Against the System: The 1968 Congress of Black Writers and the Making of Global Consciousness, and Dread Poetry and Freedom: Linton Kwesi Johnson and the Unfinished Revolution. He is also the editor of You Don’t Play with Revolution: The Montreal Lectures of C.L.R. James. Suggested donations: $6 / $10 / $15 sliding scale No one turned away for inability to pay MEP Events at The Peoples Forum 320 West 37th Street/New York City marxedproject.org/peoplesforum.org just a few blocks from either Penn Station or Port Authority. -

![Review “African [Women] A-Liberate Zimbabwe”](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9701/review-african-women-a-liberate-zimbabwe-809701.webp)

Review “African [Women] A-Liberate Zimbabwe”

Review “African [Women] a-Liberate Zimbabwe” [1] : Review of Reclaiming Zimbabwe: The Exhaustion of the Patriarchal Model of Liberation by Horace Campbell, David Philip Publishers, Cape Town, South Africa, 2003. Shereen Essof The crisis of the state and governance in Zimbabwe has divided Zimbabweans, the country's southern African neighbours and the international community. Given Africa's big challenges – HIV/AIDS, trade, debt, food shortages, environmental crises and unending civil wars ravaging failed states – it is striking that such significant symbolic political investment has been made in the fate of a small country (12 million people) with a rapidly declining economy no particular strategic significance. There is no doubt that the Zimbabwean situation is serious, or that President Robert Mugabe bears responsibility for the deep political crisis pervading the country, state-sanctioned repression and the mismanagement of the economy. The standard of living in Zimbabwe is worse today than it was in 1980. Some 65% of Zimbabweans are living either in poverty or extreme poverty (Campbell, 300). By July 2003, Zimbabwe had a currency shortage and an inflation rate of 450%. Its citizens face long queues for everything from bread to petrol. An agriculturally productive country has been reduced to seeking food aid. Further, Zimbabwe has one of the highest rates of HIV/AIDS infection on the continent, giving rise to a staggering 2 000 deaths per week. The pandemic has devastated Zimbabwe's social fabric and its productive and reproductive capacities (4, 169-70, 300), a tragic reality that has been aggravated by the sexist and homophobic public policies and practices of the Mugabe regime. -

The Impact of Walter Rodney and Progressive Scholars on the Dar Es

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Tile IIBPact ofW .......... y .ad Progressive SeII.lln .. tile Dar es S..... SdIooI Horace Campbell Utqfiti Vol VIII No.2. 1986. Journal SmIOT lActurer. of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University ol/Jar es $4Itwn University of Oar es Salaam The University of Oar es Salaam in Tanzania faces the same problem of the contradictory nature of University education which is to be found in all States of Africa. Discontinuities between the pre-colonial, colonial and post~ 9Ol0nial patterns and methods of education continue as the present components of formal education strive to retain relevance to the needs of the society. The interconnections between education and various aspects of the life of the socie- ty.remain problematic in so far as the structures, content and language of hi&her education in Tanzania and indeed the rest of Africa remain geared to the train- ing of high level manpower. This requirement of skilled manpower meets the needs of the administration of the people but the needs of the producers are not immediately met by the University. Throughout the African continent, the educational needs of the vast majority of the toilers are met by the transmis- sion of skills and agricultural knowledge accumulated over centuries and con- veyed through practical experience rather than in a classroom. -

Preliminary Program Full V3.0

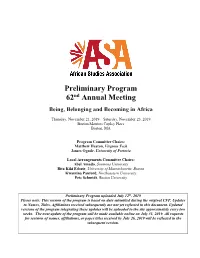

Preliminary Program nd 62 Annual Meeting Being, Belonging and Becoming in Africa Thursday, November 21, 2019 – Saturday, November 23, 2019 Boston Marriott Copley Place Boston, MA Program Committee Chairs: Matthew Heaton, Virginia Tech James Ogude, University of Pretoria Local Arrangements Committee Chairs: Abel Amado, Simmons University Rita Kiki Edozie, University of Massachusetts, Boston Kwamina Panford, Northeastern University Eric Schmidt, Boston University Preliminary Program uploaded July 12th, 2019 Please note: This version of the program is based on data submitted during the original CFP. Updates to Names, Titles, Affiliations received subsequently are not yet reflected in this document. Updated versions of the program integrating these updates will be uploaded to the site approximately every two weeks. The next update of the program will be made available online on July 31, 2019. All requests for revision of names, affiliations, or paper titles received by July 26, 2019 will be reflected in the subsequent version. Program Theme The theme of this year’s Annual Meeting is “Being, Belonging and Becoming in Africa.” While Africa is not and never has been homogenous or unitary, the existence of the ASA is predicated on the idea that there are things that distinguish “Africa” and “Africans” from other peoples and places in the world, and that those distinctions are worth studying. In a world increasingly preoccupied with tensions over localism, nationalism, and globalism, in which so many forms of essentialism are under existential attack (and fighting back), we hope that this theme will spark scholarly reflection on what it has meant and currently means for people, places, resources, ideas, knowledge, among others to be considered distinctly “African.” As scholars have grappled with the conceptual and material effects of globalization, the various disciplines of African Studies have also embraced transnational, international, and comparative approaches in recent decades. -

GLOBAL SOUTH STUDIES Rodney, Walter

GLOBAL SOUTH STUDIES Rodney, Walter Derek Gideon Historian and labor activist Walter Rodney (1942-1980) is a figure of two major internationalist discourses which operated in the anticolonial movements of the 1960s and 70s, pan-Africanism and Marxism. Alfred López writes in the inaugural issue of The Global South that the Global South can be found in “the mutual recognition among the world’s subalterns of their shared condition at the margins of the brave new neoliberal world of globalization” (2007, 3). As a movement intellectual deeply engaged with both grassroots organizing and scholarly research, breaking down barriers between the two across continents, Rodney stands at the center of earlier such moments of “mutual recognition.” His classic historical work How Europe Underdeveloped Africa was a major intervention into the discourse of development and influenced the formation of world-systems theory as a means of understanding North-South inequalities. Rodney lived, taught and was politically active in Guyana, Jamaica, and Tanzania, and saw the political struggles against oppression by African and African-descended peoples as deeply intertwined. His 1969 The Groundings with My Brothers is a powerful statement of Pan-Africanist commitment. Rodney analyzes black oppression in Jamaica, evokes the slogan “Black Power” emerging in the United States, and argues for the slogan’s relevance in Jamaica. He also advocates for the study of African history as part of revolutionary struggle, and describes the creativity and vitality of black, working-class Rastafarian communities in Jamaica, based on his own personal relationships with them. Rodney’s commitment to Marxism also shapes the politics of The Grounding with My Brothers.