THE RED BADGE of COURAGE by Stephen Crane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Review of Sthephen Crane's the Red Badge of Courage

BOOK REVIEW OF STHEPHEN CRANE’S THE RED BADGE OF COURAGE A FINAL PROJECT in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement For S-1 Degree in American Study in English Department, Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University Submitted by: Evi Lusantie A2B007044 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DIPONEGORO UNIVERSITY SEMARANG 2012 APPROVAL Approved by Advisor, Drs. Sunarwoto, MS., MA. NIP. 194806191980031001 VALIDATION Approved by Strata I Final Examination Committee Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University Advisor, Drs. Sunarwoto, MS., MA NIP. 194806191980031001 MOTTO AND DEDICATION “Family is my priority. Because of them, I can be a good person like now. My purpose is to make them happy”. This thesis is dedicated to my beloved mother. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Alhamdulillah, “Praise be to God Almighty who has given strength and true spirit so this project on “Book review of The Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Cranes” came to a completion. On this occasion, the writer would like to thank all those people who have contributed to the completion of this research report. The deepest gratitude and appreciation is extended to Drs. Sunarwoto, MS., MA - the writer advisor-who has given her continuous guidance, helpful correction, moral support, advice and suggestion without it is doubtful that this thesis came into completion. The writer’s deepest thank also goes to the following: 1. Drs. Sunarwoto, M.S., M.A – the writer advisor – who always gives her continuous; 2. Her lovely family, who always charge her spirit in finishing this book review; 3. Her “Susilo Prabowo”, who always be the destiny in her good and bad times; 4. All the her friend, for the nice friendship. -

A Study of Stephen Crane and Tim O

Life at War and the Heroic Illusions Created to Cope with War: A Study of Stephen Crane and Tim O‘Brien By Gaye L. Allen A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Liberal Studies written under the direction of Professor Richard M. Drucker and approved by ________________________ Richard Drucker Camden, New Jersey May 2011 i Abstract of the Thesis Life at War and the Illusions Created to Cope with War: A Study of Stephen Crane and Tim O‘Brien By Gaye L. Allen Thesis Director: Professor Richard M. Drucker This thesis will examine the fictional war novels, The Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane and Going after Cacciato by Tim O‘Brien. It will examine the heroic illusions created by soldiers on the frontline as psychological coping mechanisms as a means to escape the realities of war. It will also examine how Stephen Crane and Tim O‘Brien create protagonists and characters that struggle to understand the conflicts within themselves as consequences of their developing point of view toward themselves, their war comrades, and their society‘s values and how each of these writers through observing battlefield experience comes to question the meaning of war and its effects. Stephen Crane and Tim O‘Brien investigate the moral and cultural values of their respective societies. Crane portrays the Victorian era O‘Brien examines1960‘s America. Each novel asks us to view their war with both irony and sympathy. -

Benjamin F. Fisher the Red Badge of Courage Under British Spotlights Again

Benjamin F. Fisher The Red Badge of Courage under British Spotlights Again hese pages provide information that augments my previous publications concerning discoveries about contemporaneous British opinions of The Red Badge of CourageT. I am confident that what appears in this and my earlier article [WLA Special Issue 1999] on the subject offers a mere fraction of such materials, given, for example, the large numbers of daily newspapers published in London alone during the 1890s. Files of many British periodicals and newspapers from the Crane era are no longer extant, principally because of bomb damage to repositories of such materials during wartime. The commentary garnered below, how- ever, amplifies our knowledge relating to Crane’s perennially compel- ling novel, and thus, I trust, it should not go unrecorded. If one wonders why, after a century, such a look backward might be of value to those interested in Crane, I cite a letter of Ford Maddox Ford to Paul Palmer, 11 December 1935, in which he states that Crane, along with Henry James, W.H. Hudson, and Joseph Conrad all “exercised an enormous influence on English—and later, American writing. .” Ford’s thoughts concerning Crane’s importance were essentially repeated in a later letter, to the editor of the Saturday Review of Literature.1 Despite many unreliabilities in what Ford put into print on any subject, he thor- oughly divined the Anglo-American literary climate from the 1890s to the 1930s. His ideas are representative of views of Crane in British eyes during that era and, for that matter, views that have maintained cur- rency to the present time. -

The Red Badge of Courage" and the Civil War Cara Erdheim Sacred Heart University, [email protected]

Sacred Heart University DigitalCommons@SHU English Faculty Publications English Department 2007 Private Fleming at Chancellorsville: "The Red Badge of Courage" and the Civil War Cara Erdheim Sacred Heart University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/eng_fac Part of the American Literature Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Erdheim, Cara, "Private Fleming at Chancellorsville: "The Red Badge of Courage" and the Civil War" (2007). English Faculty Publications. Paper 10. http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/eng_fac/10 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 80 Studies in American Naturalism became more cemented within popular culture, its continuing presence hints that naturalism and modernism have more in common than tradi- tionally thought. Despite the popularity of Horatio Alger stories and the nation’s melt- ing pot roots, people were genuinely scared of what they viewed as the great, unwashed masses destroying their little piece of paradise. The power of Imagining the Primitive in Naturalist and Modernist Literature is in its revelation of how writers relied on the idea of the primitive to evoke the era’s fears and aspirations. Rossetti shows how the primitive enables writers across different eras to depict particular “qualities of American identity.” Rossetti makes an important contribution to the study of naturalist and modernist literature. By focusing on a character type, rather than a strictly defined era in literary history, she shows the fluidity of literary eras. -

Stephen Crane's Private War: the Red Badge of Courage1

Stephen Crane’s Private War: The Red Badge of Courage1 --Louis A. Renza, Dartmouth College In certain ways, Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage concerns more how a later American generation has forgotten the Civil War than a realistic depiction of how that war was actually fought from the viewpoint of the common soldier. Such forgetting paradoxically occurs through the way Americans remembered--and continue to remember--the Civil War: the emphasis on major campaigns won or lost, or, to use the title of a text regarded as one of Crane’s major sources for the novel, on “battles and leaders of the Civil War.” The Red Badge, of course, obfuscates both battles (is the scene Chancellorsville?) and leaders (Fleming’s army “superiors” go unnamed, the exception, “MacChesnay,” being an unknown regiment colonel). The major cause of the war is notable, too, for its having become virtually forgotten, perhaps motivated by middle-class, post-Reconstructionist sentiments; the only sign of it appears with the “negro” teamster who “sits ‘mournfully down’ to lament his loss of an audience” (Kaplan 277). In Crane’s novel, even the warring parties have lost their political specificity, being now reduced in cultural memory to visual metaphors, the “blue” and “gray” armies, as if mere figures in some game. One can regard such forgetfulness as a duplication, so to speak, of Crane’s general vision of epistemological solipsism. Just as Fleming never knows what his fellow soldiers are thinking (“His failure to discover any mite of resemblance in their view points made him more miserable than before” [2:428]), or from one moment to the next how to regard his desertion, so critics continually debate the issue of his final growth: either that he achieves it, or, relying on manuscript evidence, that Crane frames his protagonist’s own sense of growth (“He felt a quiet manhood, nonassertive but Renza: Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage 1 of sturdy and strong blood” [24:538]) in a definitively ironic (sic) light. -

SUMMARY This Thesis Is an Investigation About Stephen Crane Who Was Born on November 1, 1871, and Died on June 5, 1900. He Was A

UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA SUMMARY This thesis is an investigation about Stephen Crane who was born on November 1, 1871, and died on June 5, 1900. He was an American novelist, short story writer, poet, and journalist. Also this work is an analysis of his major work, The Red Badge of Courage. This investigation is focused on Crane´s life, how he grew up, why and how he became a writer. Another objective of this thesis is to see what kind of style he used in his writings; also it is necessary to review some important aspects of the American Civil War such as its causes, political aspects, and consequences in order to understand his famous work, The Red Badge of Courage, better. So the analysis of this work gives people an idea of the distinctive style which is often described as Naturalistic, Realistic, Impressionistic or a mixture of the three. Also this work shows how Crane wrote the novel without having had any battle experience thus making people who read this work think that Stephen Crane was one of the Civil War soldiers. KEY WORDS: Stephen Crane, The Red Badge of Courage, Analysis, Style, Impressionism, Naturalism, Realism, Major works, American Civil War, Slavery, Gabriela Faicán y Paola Malla 1 UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA INDEX PAGES SUMMARY………………………………….……………………………………....1 AUTHORSHIP……………………………………………………………………...4 DEDICATION………………………………………………………………...……..9 ACKNOWLEDGMENT………….….………………………….………..….…….11 INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………….13 1. CHAPTER ONE: STEPHEN CRANE´S LIFE 1.1 Early years…………………………………………………………………15 1.2 Education…………………………………………………………………..17 1.3 Full-time writer …………………………………………………………….19 1.4 Travels and fame …………………………………………………………22 1.5 Cora Taylor and the Commodore shipwreck…………………………..25 1.6 Death……………………………………………………………………….27 2. -

A Framework for Understanding Stephen Crane's "The Red Badge of Courage"

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1990 Progress of the Regiment: A Framework for Understanding Stephen Crane's "The Red Badge of Courage" Timothy John Brotherton College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Brotherton, Timothy John, "Progress of the Regiment: A Framework for Understanding Stephen Crane's "The Red Badge of Courage"" (1990). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625601. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-0fry-tn10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROGRESS OF THE REGIMENT: A FRAMEWORK FOR UNDERSTANDING STEPHEN CRANE S THE RED BADGE OF COURAGE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Captain Timothy Brotherton 1990 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Timoth J. Brotherton Approved, July 1990 ~keJXiLs Elsa Nettels Christopher MacGowan ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my appreciation to Professor Elsa Nettels for showing how my personal (and rewarding) experiences with American soldiers could connect with my literary investigations. I also appreciate the dedication and hard work of the essay's other two readers, Christopher MacGowan and Richard Lowry. -

The Red Badge of Courage” Dr

International Journal of Humanities & Social Science Studies (IJHSSS) A Peer-Reviewed Bi-monthly Bi-lingual Research Journal ISSN: 2349-6959 (Online), ISSN: 2349-6711 (Print) Volume-III, Issue-III, November 2016, Page No. 236-242 Published by Scholar Publications, Karimganj, Assam, India, 788711 Website: http://www.ijhsss.com Stephen Crane Captures the Effect of Fear and Realism in “The Red Badge of Courage” Dr. Thamarai Selvi Lecturer, Language and Literature, University of Goroka, Papua New Guinea Abstract Stephen Crane's “The Red Badge of Courage”, a war novel set in an unnamed battle of the Civil War, most likely the Battle of Chancellorsville was indeed a famous novel. The novel was routinely named as one of the greatest war novels of all time although, interestingly enough, Crane had no personal military experience. As the story unfolded, members of a newly recruited Union regiment were debating a rumour: they were finally out of the war the next day and engaged the enemy. One young soldier, Henry Fleming, reflected on what would become of him when he got to battle - namely, would he run or would he stand and fight bravely? He enlisted because he wanted to be a hero, like the warriors of the Greek epics. His own mother, however, was not interested in his notions of bravery, and discouraged him from being enlisted. When he told her he's joined the army, she denied him a farewell scene and merely said if he found himself in a situation where he would be killed or may do something wrong, he would go with his feelings. -

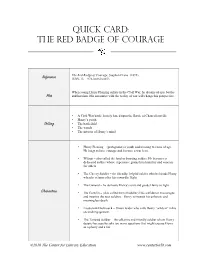

Quick Card: the Red Badge of Courage

Quick Card: The Red badge of Courage Reference The Red Badge of Courage. Stephen Crane. (1895) ISBN-13: 978-0486264653 When young Henry Fleming enlists in the Civil War, he dreams of epic battles Plot and heroism. His encounter with the reality of war will change his perspective. • A Civil War battle loosely based upon the Battle of Chancellorsville • Henry’s youth Setting • The battlefield • The woods • The interior of Henry’s mind • Henry Fleming – (protagonist) a youth endeavoring to come of age. He longs to have courage and become a war hero. • Wilson – also called the loud or boasting soldier. He becomes a dedicated soldier whose experience grants him humility and concern for others. • The Cheery Soldier – the friendly, helpful soldier who befriends Henry when he returns after his cowardly flight • The General – he demeans Henry’s unit and goads Henry to fight Characters • Jim Conklin – (also called the tall soldier) His confidence encourages and inspires the new soldiers. Henry witnesses his unheroic and meaningless death. • Lieutenant Hasbrouck – Union leader who calls Henry “wildcat” in his second engagement • The Tattered Soldier – the talkative and friendly soldier whom Henry deserts because he asks too many questions that might expose Henry as a phony and a liar ©2016 The Center for Literary Education www.centerforlit.com Man vs. Society; Man vs. Himself; Man vs. Man: Will Henry find the courage Conflict he seeks and become a war hero? Will Henry find a way to reconcile himself with his cowardly behavior? Will Henry gain experience -

The Red Badge of Courage / Stephen Crane

AG RED BADGE FM 8/9/06 8:46 AM Page i The Red Badge of Courage Stephen Crane THE EMC MASTERPIECE SERIES Access Editions SERIES EDITOR Laurie Skiba EMC/Paradigm Publishing St. Paul, Minnesota AG RED BADGE FM 8/9/06 8:46 AM Page ii Staff Credits: for EMC/Paradigm Publishing, St. Paul, Minnesota Laurie Skiba Paul Spencer Editor Art and Photo Researcher Lori Coleman Chris Nelson Associate Editor Editorial Assistant Brenda Owens Kristin Melendez Associate Editor Copy Editor Jennifer Anderson Sara Hyry Assistant Editor Contributing Writer Gia Garbinsky Christina Kolb Assistant Editor Contributing Writer for SYP Design & Production, Wenham, Massachusetts Sara Day Charles Bent Partner Partner All photos courtesy of Library of Congress. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Crane, Stephen, 1871–1900. The red badge of courage / Stephen Crane. p. cm. -- (The EMC masterpiece series access editions) Summary: During his service in the Civil War a young Union soldier matures to manhood and finds peace of mind as he comes to grips with his conflicting emotions about war. ISBN 0-8219-1981-4 1. Chancellorsville (Va.), Battle of, 1863 Juvenile fiction. [1. Chancellorsville (Va.), Battle of, 1863 Fiction. 2. United States--History-- Civil War, 1861–1865 Fiction.] I. Title. II. Series. PZ7.C852Re 199b [Fic]--dc21 99-36549 CIP ISBN 0-8219-1981-4 Copyright © 2000 by EMC Corporation All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be adapted, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, elec- tronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without permis- sion from the publisher. -

The Power of Society in the Red Badge of Courage

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU ETD Archive 2009 The Power of Society in The Red Badge Of Courage Hmoud Alotaibi Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive Part of the English Language and Literature Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Alotaibi, Hmoud, "The Power of Society in The Red Badge Of Courage" (2009). ETD Archive. 709. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive/709 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETD Archive by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POWER OF SOCIETY IN THE RED BADGE OF COURAGE HMOUD ALOTAIBI Bachelor of Arts in English King Saud University March, 2001 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTERS OF ARTS IN ENGLISH at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2009 This thesis has been approved for the Department of ENGLISH and the College of Graduate Studies by __________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Dr. Adam Sonstegard _________________________________ Department& Date Dr. Frederick J. Karem ________________________________ Department& Date Dr. John Gerlach ______________________________ Department& Date DEDICATION To my family. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Adam Sonstegard, who worked with me step by step, until this thesis was completed. I will never forget his advice, patience, and exquisite help that brought this thesis to its final draft. Dr. John Gerlach introduced me to American literature and because of the vast knowledge he shared with me, I have selected this novel, The Red Badge of Courage, to be the focus of my thesis. -

MICHAEL W. SCHAEFER Professor of English, University of Central

MICHAEL W. SCHAEFER Professor of English, University of Central Arkansas Education Ph.D. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 5/12/90 M.A. North Carolina State University 12/17/83 B.A. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 5/14/73 Academic Positions Professor, University of Central Arkansas, 2001- Associate Professor, University of Central Arkansas, 1995-2001 Assistant Professor, University of Central Arkansas, 1991-95 Instructor, University of Central Arkansas, 1989-91 Lecturer, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1988-89 Teaching Fellow, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1986-87 Teaching Assistant, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1981-86, 1987-88 Teaching Assistant, North Carolina State University, 1979-80 Teaching Activities Composition I Composition II World Literature II Introduction to Fiction American Literature I American Literature II Readings for Honors Degree (various sections on nineteenth- and twentieth-century American Literature) Studies in Literature (Literature and Psychoanalytic Theory, Race and the American Novel) The American Novel to 1900 American Romanticism and Realism American Romantic Period Graduate Independent Study (sections on American local-color writing and its relationship to nineteenth-century women's literature, William Faulkner, Stephen Crane, Edith Wharton, American Literature and Race) Publications Books "Just What War Is": Realism in the Civil War Writings of John W. De Forest and Ambrose Bierce . Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1997. A Reader's Guide to the Short Stories of Stephen Crane. New York: G. K. Hall, 1996. Encyclopedia of American War Literature . Ed. Philip K. Jason, Mark A. Graves, Robert D. Madison, and Michael W.