Online Appendix (474.67

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing a New Perspective to Study the Health of Survivors of Sichuan Earthquakes in China

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Crossref Liang and Wang Health Research Policy and Systems 2013, 11:41 http://www.health-policy-systems.com/content/11/1/41 RESEARCH Open Access Developing a new perspective to study the health of survivors of Sichuan earthquakes in China: a study on the effect of post-earthquake rescue policies on survivors’ health-related quality of life Ying Liang1* and Xiukun Wang2 Abstract Background: Sichuan is a province in China with an extensive history of earthquakes. Recent earthquakes, including the Lushan earthquake in 2013, have resulted in thousands of people losing their homes and their families. However, there is a research gap on the efficiency of government support policies. Therefore, this study develops a new perspective to study the health of earthquake survivors, based on the effect of post-earthquake rescue policies on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of survivors of the Sichuan earthquake. Methods: This study uses data from a survey conducted in five hard-hit counties (Wenchuan, Qingchuan, Mianzhu, Lushan, and Dujiangyan) in Sichuan in 2013. A total of 2,000 questionnaires were distributed, and 1,672 were returned; the response rate was 83.6%. Results: Results of the rescue policies scale and Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36) scale passed the reliability test. The confirmatory factor analysis model showed that the physical component summary (PCS) directly affected the mental component summary (MCS). The results of structural equation model regarding the effects of rescue policies on HRQOL showed that the path coefficients of six policies (education, orphans, employment, poverty, legal, and social rescue policies) to the PCS of survivors were all positive and passed the test of significance. -

World Bank Document

CONFORMED COPY Public Disclosure Authorized LOAN NUMBER 7616-CN Loan Agreement Public Disclosure Authorized (Wenchuan Earthquake Recovery Project) between PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA Public Disclosure Authorized and INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT Dated March 20, 2009 Public Disclosure Authorized LOAN AGREEMENT AGREEMENT dated March 20, 2009, between PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA (“Borrower”) and INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT (“Bank”). The Borrower and the Bank hereby agree as follows: ARTICLE I – GENERAL CONDITIONS; DEFINITIONS 1.01. The General Conditions (as defined in the Appendix to this Agreement) constitute an integral part of this Agreement. 1.02. Unless the context requires otherwise, the capitalized terms used in the Loan Agreement have the meanings ascribed to them in the General Conditions or in the Appendix to this Agreement. ARTICLE II – LOAN 2.01. The Bank agrees to lend to the Borrower, on the terms and conditions set forth or referred to in this Agreement, an amount equal to seven hundred ten million Dollars ($710,000,000), as such amount may be converted from time to time through a Currency Conversion in accordance with the provisions of Section 2.07 of this Agreement (“Loan”), to assist in financing the project described in Schedule 1 to this Agreement (“Project”). 2.02. The Borrower may withdraw the proceeds of the Loan in accordance with Section IV of Schedule 2 to this Agreement. 2.03. The Front-end Fee payable by the Borrower shall be equal to one quarter of one percent (0.25%) of the Loan amount. The Borrower shall pay the Front-end Fee not later than sixty (60) days after the Effective Date. -

Research Article Stability and Complexity Analysis of Temperature Index Model Considering Stochastic Perturbation

Hindawi Advances in Mathematical Physics Volume 2018, Article ID 2789412, 18 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2789412 Research Article Stability and Complexity Analysis of Temperature Index Model Considering Stochastic Perturbation Jing Wang Faculty of Science, Bengbu University, Bengbu 233030, China Correspondence should be addressed to Jing Wang; [email protected] Received 20 October 2017; Accepted 12 December 2017; Published 1 January 2018 Academic Editor: Giampaolo Cristadoro Copyright © 2018 Jing Wang. Tis is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. A temperature index model with delay and stochastic perturbation is constructed in this paper. It explores the infuence of parameters and stochastic factors on the stability and complexity of the model. Based on historical temperature data of four cities of Anhui Province in China, the temperature periodic variation trends of approximately sinusoidal curves of four cities are given, respectively. In addition, we analyze the existence conditions of the local stability of the temperature index model without stochastic term and estimate its parameters by using the same historical data of the four cities, respectively. Te numerical simulation results of the four cities are basically consistent with the descriptions of their historical temperature data, which proves that the temperature index model constructed has good ftting degree. It also shows that unreasonable delay parameter can make the model lose stability and improve the complexity. Stochastic factors do not usually change the trend in temperature, but they can cause high frequency fuctuations in the process of temperature evolution. -

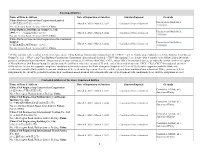

Sanctioned Entities Name of Firm & Address Date

Sanctioned Entities Name of Firm & Address Date of Imposition of Sanction Sanction Imposed Grounds China Railway Construction Corporation Limited Procurement Guidelines, (中国铁建股份有限公司)*38 March 4, 2020 - March 3, 2022 Conditional Non-debarment 1.16(a)(ii) No. 40, Fuxing Road, Beijing 100855, China China Railway 23rd Bureau Group Co., Ltd. Procurement Guidelines, (中铁二十三局集团有限公司)*38 March 4, 2020 - March 3, 2022 Conditional Non-debarment 1.16(a)(ii) No. 40, Fuxing Road, Beijing 100855, China China Railway Construction Corporation (International) Limited Procurement Guidelines, March 4, 2020 - March 3, 2022 Conditional Non-debarment (中国铁建国际集团有限公司)*38 1.16(a)(ii) No. 40, Fuxing Road, Beijing 100855, China *38 This sanction is the result of a Settlement Agreement. China Railway Construction Corporation Ltd. (“CRCC”) and its wholly-owned subsidiaries, China Railway 23rd Bureau Group Co., Ltd. (“CR23”) and China Railway Construction Corporation (International) Limited (“CRCC International”), are debarred for 9 months, to be followed by a 24- month period of conditional non-debarment. This period of sanction extends to all affiliates that CRCC, CR23, and/or CRCC International directly or indirectly control, with the exception of China Railway 20th Bureau Group Co. and its controlled affiliates, which are exempted. If, at the end of the period of sanction, CRCC, CR23, CRCC International, and their affiliates have (a) met the corporate compliance conditions to the satisfaction of the Bank’s Integrity Compliance Officer (ICO); (b) fully cooperated with the Bank; and (c) otherwise complied fully with the terms and conditions of the Settlement Agreement, then they will be released from conditional non-debarment. If they do not meet these obligations by the end of the period of sanction, their conditional non-debarment will automatically convert to debarment with conditional release until the obligations are met. -

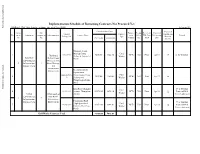

Procured Contracts February/13

Implementation Schedule of Remaining Contracts Not Procured Yet Public Disclosure Authorized 1USD=6.3 CNY (based on the exchange rate as of Nov, 2012) February/13 Estimated Base Costs Expected Comp- Sub- Procure- Prequa- Review by Expected Contract Contract Construction No. onent Component component Sub-component Contract Name ment lifica- WB (Prior Bid Opening Remark Package No. Type Duration No. No. Mothod tion /Post) Date CNY10,000 USD10,000 (month) Wuxiaojie Storm Drainage Pump Civil 1 HSFS/S5/C1 7200.00 1142.86 NCB NO Prior Jan/13 17 in the bidding Huaishang Station & Associated Works Suburban District Flood Public Disclosure Authorized Works Environment Management & 3 Infrastructure 3 Storm Drainage Improvement and Infrastructure Reconstruction & Improvement Expansion of HSFS/S5/C6-N- Wangxiaogou Pump Civil 2 3478.00 552.06 NCB NO Post Apr/13 16 B Stations and Works Wangxiaogou Intake Ditch Public Disclosure Authorized Lilou Road (Donghai New Addition Civil 4 LZUI/S10/C1 Avenue - Huangshan 10572.00 1678.10 NCB NO Prior Apr/13 12 Project of Mid- Works Urban Urban(south of Avenue) Term Adjustment Environment Huai River) 2 3 Infrastructure Infrastructure Fengandong Road Improvement Improvement New Addition (High Speed Rail Civil 5 LZUI/S10/C2 10351.00 1643.02 NCB NO Prior Apr/13 12 Project of Mid- Culvert - Mid. Ring Works Term Adjustment Road) Civil Works Contracts Total 31601.00 5016.03 Public Disclosure Authorized Preparation of Rules and Operational Procedures for Mohekou Industrial Bid evaluation 6 C Zone (MIZ), and - 20 TA QCBS - Prior Aug/12 12 is in process Bidding Document to Select a Professional Technical Operator for MIZ Services, 4 Training and Study Tour Institutional & Financial Bid evaluation 7 E - 32 TA QBS - Prior Aug/12 12 Strengthening of is in process Utility Companies Strategy and Selection of Bengbu 8 F - 21 TA CQS - Prior Mar/13 7 Water Sector Development TA and Training Total - 73 Procured Contracts February/13 Review Estimated Cost Cost of Signed Contract Procure- Contract by WB Bid Opening Contract No. -

Analysis of Historic Rainfall Characteristics for Robust Wheat Cropping in North Anhui

Analysis of historic rainfall characteristics for robust wheat cropping in North Anhui Hui Su, Yibo Wu, Yulei Zhu, Youhong Song Anhui Agricultural University, School of Agronomy, Hefei, 233036. Corresponding email: [email protected] Abstract Northern part of Anhui is one of major wheat producing areas in China. The total amount of rainfall is sufficient for wheat season; however, it is unevenly distributed at the different growth stages, resulting in risk of yield losses. In order to optimise the cultivation in North Anhui, it is essential to characterise the rainfall pattern for wheat growth particularly in the critical period (i.e. the months of sowing and harvesting). By analysing the rainfall data from 1955 to 2017, this study characterised the rainfall pattern from six sites representing different regions of North Anhui. The frequency of continuous rainfall days during sowing and harvesting periods were quantified based on 63 years rainfall distribution. The characterisation of rainfall in six representative sites in North Anhui were able to be used to guide wheat sowing and harvesting, which could help farmers to make decisions and avoid likelihood of cropping risks. Key Words Winter wheat, rainfall pattern, sustainable cropping, China Introduction Huang-Huai-Hai plain is a major wheat production area in China (Yang, 2018). The northern part of Anhui province belongs to south Huang-Huai-Hai plain. The wheat sowing time normally varies 1 week before or after October 15 and harvesting is tightly closing to May 31 in the following year. The climate characteristics particularly rainfall distribution over the season are complicated in North Anhui as it is in the transitional zone between the North and South China. -

Analysis of Accumulation Models of Middle Permian in Northwest Sichuan Basin

EARTH SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL GEOLOGY Earth Sci. Res. J. Vol. 24, No. 4 (December, 2020): 419-428 Analysis of accumulation models of middle Permian in Northwest Sichuan Basin Bin Li1,2,*, Qiqi Li3, Wenhua Mei2, Qingong Zhuo4, Xuesong Lu4 1State Key Laboratory of Shale Oil and Gas Enrichment Mechanisms and Effective Development, Wuxi, 214126 2School of Geoscience and Technology, Southwest Petroleum University, Chengdu, 610500 3School of Earth Resources, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, 430074; 4PetroChina Research Institute of Petroleum Exploration and Development, Beijing 100083, China *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Keywords: Northwest of Sichuan Basin; Great progress has been made in middle Permian exploration in Northwest Sichuan in recent years, but there are still Structure Evolution of Foreland Basin; Middle many questions in understanding the hydrocarbon accumulation conditions. Due to the abundance of source rocks and Permian; Paleozoic; Accumulation conditions; the multi-term tectonic movements in this area, the hydrocarbon accumulation model is relatively complex, which has Accumulation Model. become the main problem to be solved urgently in oil and gas exploration. Based on the different tectonic backgrounds of the middle Permian in northwest Sichuan Basin, the thrust nappe belt, the hidden front belt, and the depression belt are taken as the research units to comb and compare the geologic conditions of the middle Permian reservoir. The evaluation of source rocks and the comparison of hydrocarbon sources suggest that the middle Permian hydrocarbon mainly comes from the bottom of the lower Cambrian and middle Permian, and the foreland orogeny promoted the thermal evolution of Paleozoic source rocks in northwest Sichuan to high maturity and over maturity stage. -

2016 Annual Report.PDF

HAITONG SECURITIES CO., LTD. 海通證券股份有限公司 Annual Report 2016 2016 Annual Report 年度報告 CONTENTS Section I Definition and Important Risk Warnings 3 Section II Company Profile and Key Financial Indicators 7 Section III Summary of the Company’s Business 23 Section IV Report of the Board of Directors 28 Section V Significant Events 62 Section VI Changes in Ordinary Share and Particulars about Shareholders 91 Section VII Preferred Shares 100 Section VIII Particulars about Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management and Employees 101 Section IX Corporate Governance 149 Section X Corporate Bonds 184 Section XI Financial Report 193 Section XII Documents Available for Inspection 194 Section XIII Information Disclosure of Securities Company 195 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Board, the Supervisory Committee, Directors, Supervisors and senior management of the Company represent and warrant that this annual report (this “Report”) is true, accurate and complete and does not contain any false records, misleading statements or material omission and jointly and severally take full legal responsibility as to the contents herein. This Report was reviewed and passed at the twenty-third meeting of the sixth session of the Board. The number of Directors to attend the Board meeting should be 13 and the number of Directors having actually attended the Board meeting was 11. Director Li Guangrong, was unable to attend the Board meeting in person due to business travel, and had appointed Director Zhang Ming to vote on his behalf. Director Feng Lun was unable to attend the Board meeting in person due to business travel and had appointed Director Xiao Suining to vote on his behalf. -

World Bank Document

CONFORMED COPY LOAN NUMBER 4597 CHA Public Disclosure Authorized Loan Agreement (Huai River Pollution Control Project) between PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA and Public Disclosure Authorized INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT Dated September 24, 2001 LOAN NUMBER 4597 CHA Public Disclosure Authorized LOAN AGREEMENT AGREEMENT, dated September 24, 2001, between PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA (the Borrower) and INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT (the Bank). WHEREAS (A) the Borrower, having satisfied itself as to the feasibility and priority of the project described in Schedule 2 to this Agreement (the Project), has requested the Bank to assist in the financing of the Project; (B) the Project will be carried out by the Borrower's Provinces of Anhui and Shandong (collectively, the Project Provinces and individually, a Project Province) with the Borrower’s assistance and, as part of such assistance, the Borrower will make the proceeds of the loan provided for in Article II of this Agreement (the Loan) available to each of the Project Provinces, as set forth in this Agreement; and WHEREAS the Bank has agreed, on the basis, inter alia, of the foregoing, to extend the Loan to the Borrower upon the terms and conditions set forth in this Agreement and in the Project Agreement of even date herewith between the Bank and the Public Disclosure Authorized Project Provinces (the Project Agreement); NOW THEREFORE the parties hereto hereby agree as follows: ARTICLE I General Conditions; Definitions Section 1.01. The "General Conditions Applicable to Loan and Guarantee Agreements for Single Currency Loans" of the Bank, dated May 30, 1995, as amended through October 6, 1999 (the General Conditions), constitute an integral part of this Agreement. -

Respective Influence of Vertical Mountain Differentiation on Debris Flow Occurrence in the Upper Min River, China

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Respective infuence of vertical mountain diferentiation on debris fow occurrence in the Upper Min River, China Mingtao Ding*, Tao Huang , Hao Zheng & Guohui Yang The generation, formation, and development of debris fow are closely related to the vertical climate, vegetation, soil, lithology and topography of the mountain area. Taking in the upper reaches of Min River (the Upper Min River) as the study area, combined with GIS and RS technology, the Geo-detector (GEO) method was used to quantitatively analyze the respective infuence of 9 factors on debris fow occurrence. We identify from a list of 5 variables that explain 53.92%% of the total variance. Maximum daily rainfall and slope are recognized as the primary driver (39.56%) of the spatiotemporal variability of debris fow activity. Interaction detector indicates that the interaction between the vertical diferentiation factors of the mountainous areas in the study area is nonlinear enhancement. Risk detector shows that the debris fow accumulation area and propagation area in the Upper Min River are mainly distributed in the arid valleys of subtropical and warm temperate zones. The study results of this paper will enrich the scientifc basis of prevention and reduction of debris fow hazards. Debris fows are a common type of geological disaster in mountainous areas1,2, which ofen causes huge casual- ties and property losses3,4. To scientifcally deal with debris fow disasters, a lot of research has been carried out from the aspects of debris fow physics5–9, risk assessment10–12, social vulnerability/resilience13–15, etc. Jointly infuenced by unfavorable conditions and factors for social and economic development, the Upper Min River is a geographically uplifed but economically depressed region in Southwest Sichuan. -

China: Sichuan Earthquake Mdrcn003

Emergency appeal n° MDRCN003 China: Sichuan GLIDE n° EQ-2008-000062-CHN Operations update n° 9 4 June 2008 Earthquake Period covered by this Update: 29 May- 3 June 2008 Appeal target (current): CHF 96.7 million (USD 92.7 million or EUR 59.5 million) to support the Red Cross Society of China (RCSC) to assist around 100,000 families (up to 500,000 people) for 36 months. <click here to view the attached revised emergency appeal budget> Appeal coverage: There has been a very generous and quick response to this appeal. Many pledges of funding have been received since the revised emergency appeal was launched on 30 May to reflect the increased support of the International Federation to the Red Cross Society of China’s response to the massive humanitarian needs of this disaster. <click here for the donor response list> <click here to link to a map of the affected areas; or here for contact details> Appeal history: • This emergency appeal was revised on 30 May 2008 for CHF 96.7 million (USD 92.7 million or EUR 59.5 million) to support the Red Cross Society of China (RCSC) to assist around 100,000 families (up to 500,000 people) for 36 months. • The emergency appeal was launched on 15 May 2008 for CHF 20,076,412 (USD 19.3 million or EUR 12.4 million) for 12 months to assist 100,000 beneficiaries. • Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF): CHF 250,000 was allocated from the International Federation’s DREF to support the RCSC’s response to the earthquake. -

Lanzhou-Chongqing Railway Development – Resettlement Action Plan Monitoring Report No

Resettlement Monitoring Report Project Number: 35354 April 2010 PRC: Lanzhou-Chongqing Railway Development – Resettlement Action Plan Monitoring Report No. 1 Prepared by: CIECC Overseas Consulting Co., Ltd Beijing, PRC For: Ministry of Railways This report has been submitted to ADB by the Ministry of Railways and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s public communications policy (2005). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. The People’s Republic of China ADB Loan Lanzhou—Chongqing RAILWAY PROJECT EXTERNAL MONITORING & EVALUATION OF RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN Report No.1 Prepared by CIECC OVERSEAS CONSULTING CO.,LTD April 2010 Beijing 10 ADB LOAN EXTERNAL Monitoring Report– No. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 4 OVERVIEW..................................................................................................................................................... 5 1. PROJECT BRIEF DESCRIPTION .......................................................................................................................7 2. PROJECT AND RESETTLEMENT PROGRESS ................................................................................................10 2.1 PROJECT PROGRESS ...............................................................................................................................10 2.2 LAND ACQUISITION, HOUSE DEMOLITION AND RESETTLEMENT PROGRESS..................................................10 3. MONITORING AND EVALUATION .................................................................................................................14