THE PALACES of MEMORY a Reconstruction of District One, Cape Town, Before and After the Group Areas Act Michael Ian Weeder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A -Z | Bezugsquelle

A -Z | Bezugsquelle www.robertparker.com Wine Name Vintage Rating Price Color A A Badenhorst Family Wines Brak-Kuil Barbarossa 2015 91 NA Red A A Badenhorst Family Wines Ch Raaigras Grenache 2015 89+ NA Red A A Badenhorst Family Wines Dassiekop Granietsteen Chenin 2015 NA White Blanc 92 A A Badenhorst Family Wines Family Red Blend 2014 93 $40 Red A A Badenhorst Family Wines Family White Blend 2015 92 $40 White A A Badenhorst Family Wines Ramnasgras Cinsault 2015 89 $40 Red A A Badenhorst Family Wines Secateurs Chenin Blanc 2016 86 $16 White A A Badenhorst Family Wines Secateurs Red Blend 2015 90 $17 Red A A Badenhorst Family Wines Secateurs Rose 2016 85 $16 Rosé Alheit Vineyards Cartology Bush Vines 2015 93 $50 White Alheit Vineyards Hemelrand Vine Garden 2015 93 $47 White Alheit Vineyards La Colline Vineyard 2015 93 $100 White Alheit Vineyards Magnetic North Mountain Makstok 2015 91 $100 White Alheit Vineyards Radio Lazarus 2015 94 $100 White Altydgedacht Gewurztraminer 2015 87 $13 White Altydgedacht Methode Cap Classique 2014 86 $19 White Altydgedacht Pinotage 2015 89 $16 Red Altydgedacht Sauvignon Blanc 2016 86 $13 White Anthonij Rupert Wines Cabernet Franc 2011 88 NA Red Anthonij Rupert Wines Optima 2013 87 NA Red Anthonij Rupert Wines Proprietary Red Blend 2010 90 NA Red Anwilka 2013 92 $50 Red Anwilka Petit Frere 2013 87 $20 Red Asara Cape Fusion 2014 87 $13 Red Asara The Bell Tower 2012 87 $25 Red Asara Vineyard Collection Chenin Blanc 2015 84 $13 White Ashbourne 2015 92 $50 - 55 Red Ashbourne Sauvignon Blanc Chardonnay 2015 88 -

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa January 21 - February 2, 2012 Day 1 Saturday, January 21 3:10pm Depart from Minneapolis via Delta Air Lines flight 258 service to Cape Town via Amsterdam Day 2 Sunday, January 22 Cape Town 10:30pm Arrive in Cape Town. Meet your MCI Tour Manager who will assist the group to awaiting chartered motorcoach for a transfer to Protea Sea Point Hotel Day 3 Monday, January 23 Cape Town Breakfast at the hotel Morning sightseeing tour of Cape Town, including a drive through the historic Malay Quarter, and a visit to the South African Museum with its world famous Bushman exhibits. Just a few blocks away we visit the District Six Museum. In 1966, it was declared a white area under the Group areas Act of 1950, and by 1982, the life of the community was over. 60,000 were forcibly removed to barren outlying areas aptly known as Cape Flats, and their houses in District Six were flattened by bulldozers. In District Six, there is the opportunity to visit a Visit a homeless shelter for boys ages 6-16 We end the morning with a visit to the Cape Town Stadium built for the 2010 Soccer World Cup. Enjoy an afternoon cable car ride up Table Mountain, home to 1470 different species of plants. The Cape Floral Region, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is one of the richest areas for plants in the world. Lunch, on own Continue to visit Monkeybiz on Rose Street in the Bo-Kaap. The majority of Monkeybiz artists have known poverty, neglect and deprivation for most of their lives. -

Film Locations in TMNP

Film Locations in TMNP Boulders Boulders Animal Camp and Acacia Tree Murray and Stewart Quarry Hillside above Rhodes Memorial going towards Block House Pipe Track Newlands Forest Top of Table Mountain Top of Table Mountain Top of Table Mountain Noordhoek Beach Rocks Misty Cliffs Beach Newlands Forest Old Buildings Abseil Site on Table Mountain Noordhoek beach Signal Hill Top of Table Mountain Top of Signal Hill looking towards Town Animal Camp looking towards Devils Peak Tafelberg Road Lay Byes Noordhoek beach with animals Deer Park Old Zoo site on Groote Schuur Estate : External Old Zoo Site Groote Schuur Estate ; Internal Oudekraal Oudekraal Gazebo Rhodes Memorial Newlands Forest Above Rhodes Memorial Rhodes Memorial Rhodes Memorial Rhodes Memorial Rhodes Memorial Kramat on Signal Hill Newlands Forest Platteklip Gorge on the way to the top of Table Mountain Signal Hill Oudekraal Deer Park Misty Cliffs Misty Cliffs Tracks off Tafelberg Road coming down Glencoe Quarry Buffels Bay at Cape Point Silvermine Dam Desk on Signal Hill Animal Camp Cecelia Forest Cecelia Forest Cecilia Forest Buffels Bay at Cape Point Link Road at Cape Point Cape Point at the Lighthouse Precinct Acacia Tree in the Game camp Slangkop Slangkop Boardwalk near Kommetjie Kleinplaas Dam Devils Peak Devils Peak Noordhoek LookOut Chapmans Peak Noordhoek to Hout Bay Dias Beach at CapePoint Cape Point Cape Point Oudekraal to Twelve Apostles Silvermine Dam . -

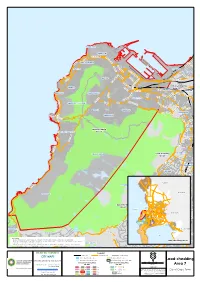

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

Cape Town's Failure to Redistribute Land

CITY LEASES CAPE TOWN’S FAILURE TO REDISTRIBUTE LAND This report focuses on one particular problem - leased land It is clear that in order to meet these obligations and transform and narrow interpretations of legislation are used to block the owned by the City of Cape Town which should be prioritised for our cities and our society, dense affordable housing must be built disposal of land below market rate. Capacity in the City is limited redistribution but instead is used in an inefficient, exclusive and on well-located public land close to infrastructure, services, and or non-existent and planned projects take many years to move unsustainable manner. How is this possible? Who is managing our opportunities. from feasibility to bricks in the ground. land and what is blocking its release? How can we change this and what is possible if we do? Despite this, most of the remaining well-located public land No wonder, in Cape Town, so little affordable housing has been owned by the City, Province, and National Government in Cape built in well-located areas like the inner city and surrounds since Hundreds of thousands of families in Cape Town are struggling Town continues to be captured by a wealthy minority, lies empty, the end of apartheid. It is time to review how the City of Cape to access land and decent affordable housing. The Constitution is or is underused given its potential. Town manages our public land and stop the renewal of bad leases. clear that the right to housing must be realised and that land must be redistributed on an equitable basis. -

Your Guide to Myciti

Denne West MyCiTi ROUTES Valid from 29 November 2019 - 12 january 2020 Dassenberg Dr Klinker St Denne East Afrikaner St Frans Rd Lord Caledon Trunk routes Main Rd 234 Goedverwacht T01 Dunoon – Table View – Civic Centre – Waterfront Sand St Gousblom Ave T02 Atlantis – Table View – Civic Centre Enon St Enon St Enon Paradise Goedverwacht 246 Crown Main Rd T03 Atlantis – Melkbosstrand – Table View – Century City Palm Ln Paradise Ln Johannes Frans WEEKEND/PUBLIC HOLIDAY SERVICE PM Louw T04 Dunoon – Omuramba – Century City 7 DECEMBER 2019 – 5 JANUARY 2020 MAMRE Poeit Rd (EXCEPT CHRISTMAS DAY) 234 246 Silverstream A01 Airport – Civic Centre Silwerstroomstrand Silverstream Rd 247 PELLA N Silwerstroom Gate Mamre Rd Direct routes YOUR GUIDE TO MYCITI Pella North Dassenberg Dr 235 235 Pella Central * D01 Khayelitsha East – Civic Centre Pella Rd Pella South West Coast Rd * D02 Khayelitsha West – Civic Centre R307 Mauritius Atlantis Cemetery R27 Lisboa * D03 Mitchells Plain East – Civic Centre MyCiTi is Cape Town’s safe, reliable, convenient bus system. Tsitsikamma Brenton Knysna 233 Magnet 236 Kehrweider * D04 Kapteinsklip – Mitchells Plain Town Centre – Civic Centre 245 Insiswa Hermes Sparrebos Newlands D05 Dunoon – Parklands – Table View – Civic Centre – Waterfront SAXONSEAGoede Hoop Saxonsea Deerlodge Montezuma Buses operate up to 18 hours a day. You need a myconnect card, Clinic Montreal Dr Kolgha 245 246 D08 Dunoon – Montague Gardens – Century City Montreal Lagan SHERWOOD Grosvenor Clearwater Malvern Castlehill Valleyfield Fernande North Brutus -

Two Rivers Urban Park Contextual Framework Review and Preliminary Heritage Study

1 TWO RIVERS URBAN PARK CONTEXTUAL FRAMEWORK REVIEW AND PRELIMINARY HERITAGE STUDY Phase One Report Submitted by Melanie Attwell and Associates in association with ARCON Heritage and Design, and ACO Associates on behalf of NM & Associates Planners and Designers [email protected] 2 Caxton Close Oakridge 7806 021 7150330 First submitted: November 2015 Resubmitted: May 2016 2 Table of Contents List of Figures....................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 4 List of Acronyms ................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Report Structure ....................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Brief and Scope of Work ......................................................................................................... 7 2. Limitations ....................................................................................................................................... 7 3. Location ......................................................................................................................................... -

Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010

Then and Now: Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010 Julian A Jacobs (8805469) University of the Western Cape Supervisor: Prof Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie Masters Research Essay in partial fulfillment of Masters of Arts Degree in History November 2010 DECLARATION I declare that „Then and Now: Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010‟ is my own work and that all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. …………………………………… Julian Anthony Jacobs i ABSTRACT This is a study of activists from Manenberg, a township on the Cape Flats, Cape Town, South Africa and how they went about bringing change. It seeks to answer the question, how has activism changed in post-apartheid Manenberg as compared to the 1980s? The study analysed the politics of resistance in Manenberg placing it within the over arching mass defiance campaign in Greater Cape Town at the time and comparing the strategies used to mobilize residents in Manenberg in the 1980s to strategies used in the period of the 2000s. The thesis also focused on several key figures in Manenberg with a view to understanding what local conditions inspired them to activism. The use of biographies brought about a synoptic view into activists lives, their living conditions, their experiences of the apartheid regime, their brutal experience of apartheid and their resistance and strength against a system that was prepared to keep people on the outside. This study found that local living conditions motivated activism and became grounds for mobilising residents to make Manenberg a site of resistance. It was easy to mobilise residents on issues around rent increases, lack of resources, infrastructure and proper housing. -

South Africa and Cape Town 1985-1987

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. A Tale of Two Townships: Race, Class and the Changing Contours of Collective Action in the Cape Town Townships of Guguletu and Bonteheuwel, 1976 - 2006 Luke Staniland A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the PhD University of Edinburgh 2011 i Declaration The author has been engaged in a Masters by research and PhD by research programme of full-time study in the Centre of African Studies under the supervision of Prof. Paul Nugent and Dr. Sarah Dorman from 2004-2011 at the University of Edinburgh. All the work herein, unless otherwise specifically stated, is the original work of the author. Luke Staniland. i ii Abstract This thesis examines the emergence and evolution of ‘progressive activism and organisation’ between 1976 and 2006 in the African township of Guguletu and the coloured township of Bonteheuwel within the City of Cape Town. -

Institutional Pathways for Local Climate Adaptation

[ March 2014 ] Institutional Pathways for Local Climate Adaptation: A Comparison of Three South African Municipalities Globally, many local authorities have begun developing programmes of climate change adaptation to curb existing and expected local climate impacts. Rather than being a one-off, sector-specific 18 technical fix, effective adaptation is increasingly recognised as a process of socio-institutional learning and change. While notions of governance are coming to the fore in climate change adaptation literature, the influence of local political and bureaucratic forces is not well documented or understood, particularly in developing country contexts. This research focuses on the political, institutional and social factors shaping the initiation of climate adaptation in three South African municipalities – Cape Town, Durban and Theewaterskloof – considered local leaders in addressing climate concerns. The findings show that, with little political or fiscal support, climate change adaptation currently remains in the realm of technical planning and management, where progress is contingent on the energy, efforts and agency of individuals. There is, however, some evidence that the efforts of local champions, in concert with rising global awareness of climate change and increasing impacts on the poor and the rich alike, are beginning to create a March 2014 political opportunity to make climate change a central development issue, linked to public services, markets and employment. Institutional Pathways for Local Climate AUTHORS Anna -

The Bronze Medallists – Good to Very Good, Fine Character

OLD MUTUAL TROPHY WINE SHOW 2016 All the bronze medallists – good to very good, fine character BC CLASSES (BC): non-dessert, non-fortified wines from cellars with a production volume of between 600 and 900 litres. MC CLASSES (MC): white wines at least four years old and all other wines at least eight years old GREAT VALUE: medallists highlighted in red are priced at under R80 per 750ml bottle for white, fortified, Rosé and Blanc de Noir wines, and under R100 per 750ml for red, sparkling and unfortified dessert wines Allée Bleue Cabernet Sauvignon Merlot 2013 Allée Bleue Chenin Blanc 2015 Allée Bleue Isabeau 2014 (White Blend) Allée Bleue L'Amour Toujours 2012 (Bordeaux-Style Red Blend) Allée Bleue Shiraz 2014 Allesverloren 1704 2015 (Shiraz-Based Red Blend) Allesverloren Cabernet Sauvignon 2014 Allesverloren Red Muscadel 2015 Allesverloren Touriga Nacional 2013 Almenkerk Merlot 2013 Alto Rouge 2013 (Red Blend) Altydgedacht Gewürztraminer 2015 Anura Merlot Reserve 2014 Anura Méthode Cap Classique Brut 2011 Anura Sauvignon Blanc Unfiltered Reserve 2015 Arendskloof Cabernet Sauvignon 2014 Arendskloof Shiraz 2013 Arendskloof Tannat-Syrah 2012 Arendskloof Witkruisarend 2014 (White Blend) Asara The Bell Tower 2012 (Bordeaux-Style Red Blend) Asara Vineyard Collection Cape Fusion 2013 (Pinotage-Based Red Blend) Audacia Rooibos Wooded Shiraz 2014 Babylonstoren Nebukadnesar 2014 (Bordeaux-Style Red Blend) Babylonstoren Shiraz 2014 Babylonstoren Sprankel 2011 (Cap Classique) Backsberg Cape White Blend 2015 (BC) Backsberg Family Reserve 2014 (Bordeaux-Style -

Cape Town Townships Cultural Experience

FULL DAY TOURS The below tours are not part of the conference package. Bookings should be made directly to Scatterlings Conference & Events and not via the FSB/OECD office. Cape Town Townships Cultural Experience Enjoy the multi - cultural life of the Cape by meeting and speaking to the local communities on our full day Cape Town Township Tour. Interact with locals in their own living environments and experience the multi- diversity of our sought after city. Highlights: Bo-Kaap and exciting Malay Quarter; District Six Museum; Cape Flats; Visit a traditional shop (spaza) or tavern (shebeen) in a township; Take a ferry trip to Robben Island and walk through the former political prison (weather permitting). Click here to send your enquiry: [email protected] Aquila Game Reserve Travel through Huguenot Tunnel past beautiful De Doorns in the Hex River valley to Aquila. Welcoming refreshments, game drive, bushman paintings and lunch in an outdoor lapa. Stroll through curio and wine shop, or relax at pool before returning to Cape Town. Click here to send your enquiry: [email protected] Cape Peninsula Travel along the beautiful coastline of the Peninsula on our Cape Peninsula day tour, through historic and picturesque villages to the mythical meeting place of the two great oceans. Highlights: Travel through Sea Point, Clifton and Camps Bay; Hout Bay Harbour (optional Seal Island boat trip, not included in cost); On to Cape Point and Nature Reserve. Unforgettable plant, bird and animal life; Lunch at Cape Point; Penguin Colony; Historic Simonstown; Groot Constantia wine estate or Kirstenbosch Botanical Gardens. Click here to send your enquiry: [email protected] Cape Winelands On our Cape Winelands day tour we take you on a trip into the heart of the Cape Winelands, through breathtaking mountain ranges and fertile valleys.