Rameau's Cartesian Wonder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 7-1 French Opera Repertory 1753–62

1 Table 12-1 French Opera Repertory 1753–63 (with Court performances of opéras- comiques in 1761–63) See Table 1-1 for the period 1742–52. This Table is an overview of commissions and revivals in the elite institutions of French opera. Académie Royale de Musique and Court premieres are listed separately for each work (albeit information is sometimes incomplete). The left-hand column includes both absolute world premieres and important earlier works new to these theatres. Works given across a New Year period are listed twice. Individual entrées are mentioned only when revived separately, or to avoid ambiguity. Prologues are mostly ignored. Sources: BrennerD, KaehlerO, LagraveTP, LajarteO, Lavallière, Mercure, NG, RiceFB, SerreARM. Italian works follow name forms etc. cited in Parisian libretti. LEGEND: ARM = Académie Royale de Musique (Paris Opéra); bal. = ballet; bouf. = bouffon; CI = Comédie-Italienne; cmda = comédie mêlée d’ariettes; com. lyr. = comédie lyrique; d. gioc.= dramma giocoso; div. scen. = divertimento scenico; FB = Fontainebleau; FSG = Foire Saint-Germain; FSL = Foire Saint-Laurent; hér. = héroïque; int. = intermezzo; NG = The New Grove Dictionary of Music; NGO = The New Grove Dictionary of Opera; op. = opéra; p. = pastorale; Vers. = Versailles; < = extract from; R = revised. 1753 ALL AT ARM EXCEPT WHERE MARKED Premieres at ARM (listed first) and Court Revivals at ARM or Court (by original date) Titon & l’Aurore (p. hér., 3: La Marre, Voisenon, Atys (Lully, 1676) FB La Motte / Mondonville, Jan. 9) Phaëton (Lully, 1683) Scaltra governatrice, La (d. gioc., 3: Palomba / Fêtes Grecques et romaines, Les (Blamont, 1723) Cocchi, Jan. 25) Danse, La (<Fêtes d’Hébé, Les)(Rameau, 1739) FB Jaloux corrigé, Le (op. -

030295688.Pdf

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC THÈSE PRÉSENTÉE À L'UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À TROIS-RIVIÈRES COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DU DOCTORAT EN LETTRES PAR ALEXANDRE LANDRY RHÉTORIQUE DES DISCOURS ANTIPHILOSOPHIQUES DE L ENCYCLOPÉDIE A L4 RÉVOLUTION DÉCEMBRE 2011 Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Service de la bibliothèque Avertissement L’auteur de ce mémoire ou de cette thèse a autorisé l’Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières à diffuser, à des fins non lucratives, une copie de son mémoire ou de sa thèse. Cette diffusion n’entraîne pas une renonciation de la part de l’auteur à ses droits de propriété intellectuelle, incluant le droit d’auteur, sur ce mémoire ou cette thèse. Notamment, la reproduction ou la publication de la totalité ou d’une partie importante de ce mémoire ou de cette thèse requiert son autorisation. 11 REMERCIEMENTS Mes prenuers remerciements vont à M. Marc André Bernier qui, dans les dix dernières années, a su me transmettre sa passion pour la recherche et son amour pour les lettres. Il m'a apporté un soutien inestimable durant ce parcours, autant par sa vaste érudition que par sa générosité sans borne et sa grande humanité. Je tiens également à témoigner toute ma reconnaissance à M. Didier Masseau : grâce à ses travaux et à ses conseils avisés, il a grandement contribué à donner à cette recherche le souffle qui l'anime maintenant. M. Masseau a toujours insisté pour que mes travaux se démarquent des autres et sortent des sentiers battus. Pour sa connaissance inestimable de l'esprit de la Compagnie de Jésus et pour nos entretiens toujours aussi plaisants que stimulants, un grand merci à mon ami Yves Bourassa. -

Download Download

FGSDGSDFGDFGFDGFGSDGSDFGDFGFDG JTA - Journal of Theatre Anthropology 1 1 JTA JTA J J OURNA OURNA OURNA OURNA T T AT AT AT AT A A NTOPOLOGY NTOPOLOGY JOURNAJOURNA TATTAT ANTOPOLOGYANTOPOLOGY T T ISSN 2784-8167ISSN 2784-8167 ISBN 978-88-5757-809-5ISBN 978-88-5757-809-5 MIMESIS MIMESIS 1 2021 1 2021 Mimesis EdizioniMimesis Edizioni www.mimesisedizioni.itwww.mimesisedizioni.it 22,00 euro22,00256 euro 9 7 8 8 895 77 8587885079 55 7 8 0 9 5 257 JTA JOURNAL OF THEATRE ANTHROPOLOGY NUMBER 1 - THE ORIGINS 2021 MIMESIS 258 Journal of Theatre Anthropology Annual Journal founded by Eugenio Barba JTAJTA In collaboration with International School of Theatre Anthropology (ISTA), JOURNAL OF THEATRE ANTHROPOLOGY Odin Teatret Archives (OTA), Centre for Theatre Laboratory Studies (CTLS) Department of Dramaturgy Founded by Eugenio Barba Aarhus University With the support of NUMBER 1 - THE ORIGINS Fondazione Barba Varley March 2021 © 2021 Journal of Theatre Anthropology and Author(s) This is an open access journal Editor distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) Eugenio Barba (Odin Teatret, Denmark) Journal’s website: https://jta.ista-online.org Printed copies are available at the Publisher’s website Managing Editor Leonardo Mancini (Verona University, Italy) Editorial correspondence and contributions should be sent Editorial Board to the managing editor Leonardo Mancini: [email protected] Simone Dragone (Genoa University, Italy / Odin Teatret Archives) Rina Skeel (Odin Teatret, Denmark) Julia Varley -

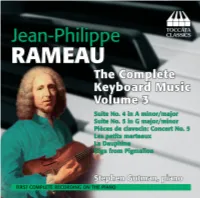

Toccata Classics TOCC0052 Notes

RAMEAU ON THE PIANO, VOLUME THREE 1 by Graham Sadler The two suites recorded on this disc are from the Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin of 1729 or 1730, Rameau’s final collection of solo keyboard music.2 Like those of his Pièces de clavessin (1724), they are contrasted both in tonality and character. The Suite in A minor and major is dominated by dances and includes only three character pieces, whereas the Suite in G major and minor consists almost exclusively of pieces with character titles. In its make-up if not its style, the latter thus follows the example of François Couperin, whose first three books of pièces de clavecin (1713, 1717 and 1722) had established the vogue for descriptive pieces. In that sense, Rameau may be regarded as somewhat conservative in devoting half of his two mature solo collections to suites of the more traditional type. Suite No. 4 in A minor and major Conservative they may be, but the dance movements of the Nouvelles suites are among the most highly P developed in the repertory, the first two particularly so. The Allemande 1 unfolds with an effortless grace, its unerring sense of direction reinforced by the many sequential passages. At the end of both sections, the duple semiquaver motion gives way unexpectedly to triplet motion, providing a memorable ‘rhyme’ to the two parts of the movement. The Courante 2, more than twice as long as its predecessors in Rameau’s output, displays a technical sophistication without parallel in the clavecin repertory. Three themes interlock in mainly three- part counterpoint – a bold motif in rising fourths, and two accompanying figures in continuous quavers, the one in sinuous stepwise movement, the other comprising cascading arpeggios. -

“Modern” Philosophy: Introduction

“Modern” Philosophy: Introduction [from Debates in Modern Philosophy by Stewart Duncan and Antonia LoLordo (Routledge, 2013)] This course discusses the views of various European of his contemporaries (e.g. Thomas Hobbes) did see philosophers of the seventeenth century. Along with themselves as engaged in a new project in philosophy the thinkers of the eighteenth century, they are con- and the sciences, which somehow contained a new sidered “modern” philosophers. That might not seem way of explaining how the world worked. So, what terribly modern. René Descartes was writing in the was this new project? And what, if anything, did all 1630s and 1640s, and Immanuel Kant died in 1804. these modern philosophers have in common? By many standards, that was a long time ago. So, why is the work of Descartes, Kant, and their contempor- Two themes emerge when you read what Des- aries called modern philosophy? cartes and Hobbes say about their new philosophies. First, they think that earlier philosophers, particu- In one way this question has a trivial answer. larly so-called Scholastic Aristotelians—medieval “Modern” is being used here to describe a period of European philosophers who were influenced by time, and to contrast it with other periods of time. So, Aristotle—were mistaken about many issues, and modern philosophy is not the philosophy of today as that the new, modern way is better. (They say nicer contrasted with the philosophy of the 2020s or even things about Aristotle himself, and about some other the 1950s. Rather it’s the philosophy of the 1600s previous philosophers.) This view was shared by and onwards, as opposed to ancient and medieval many modern philosophers, but not all of them. -

Cpo 555 156 2 Booklet.Indd 1 12.06.2020 09:36:39 Jean-Philippe Rameau

Jean-Philippe Rameau Pigmalion · Dardanus Suites & Arias Anders J. Dahlin L’Orfeo Barockorchester Michi Gaigg cpo 555 156_2 Booklet.indd 1 12.06.2020 09:36:39 Jean-Philippe Rameau cpo 555 156_2 Booklet.indd 2 12.06.2020 09:36:39 Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764) Pigmalion Acte-de-ballet, 1748 Livret by Sylvain Ballot de Sauvot (1703–60), after ‘La Sculpture’ from Le Triomphe des arts (1700) by Houdar de la Motte (1672–1731) (selected movements: Suite & Arias) 1 Ouverture 4'41 2 [Air,] ‘Fatal Amour’ (Pigmalion) 3'22 3 Air. Très lent – Gavotte gracieuse – Menuet – Gavotte gai – Chaconne vive – 5'44 Loure – Passepied vif – Rigaudon vif – Sarabande pour la Statue – Tambourin 4 Air gai 2'19 5 Pantomime niaise 0'44 6 2e Pantomime très vive 2'07 7 Ariette, ‘Règne Amour’ (Pigmalion) 4'35 8 Air pour les Graces, Jeux et Ris 0'50 9 Rondeau Contredanse 1'37 cpo 555 156_2 Booklet.indd 3 12.06.2020 09:36:39 Dardanus Tragedie en musique, 1739 (rev. 1744, 1760) Livret by Charles-Antoine Leclerc de La Bruère (1716–54) (selected movements: Suite & Arias) 10 Ouverture 4'13 11 Prologue, sc. 1: Air pour les [Jeux et les] Plaisirs [et la Jalousie et sa Suite] 1'06 12 Air pour les [Jeux et les] Plaisirs 1'05 13 Prologue, sc. 2: Air gracieux [pour les Peuples de différentes nations] 1'30 14 Rigaudon 1'41 15 Act 1, sc. 3: Air vif 2'46 16 Rigaudons 1 et 2 3'36 17 Act 2, sc. 1: Ritournelle vive 1'08 18 Act 4, sc. -

Malebranche's Augustinianism and the Mind's Perfection

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations Spring 2010 Malebranche's Augustinianism and the Mind's Perfection Jason Skirry University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Skirry, Jason, "Malebranche's Augustinianism and the Mind's Perfection" (2010). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 179. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/179 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/179 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Malebranche's Augustinianism and the Mind's Perfection Abstract This dissertation presents a unified interpretation of Malebranche’s philosophical system that is based on his Augustinian theory of the mind’s perfection, which consists in maximizing the mind’s ability to successfully access, comprehend, and follow God’s Order through practices that purify and cognitively enhance the mind’s attention. I argue that the mind’s perfection figures centrally in Malebranche’s philosophy and is the main hub that connects and reconciles the three fundamental principles of his system, namely, his occasionalism, divine illumination, and freedom. To demonstrate this, I first present, in chapter one, Malebranche’s philosophy within the historical and intellectual context of his membership in the French Oratory, arguing that the Oratory’s particular brand of Augustinianism, initiated by Cardinal Bérulle and propagated by Oratorians such as Andre Martin, is at the core of his philosophy and informs his theory of perfection. Next, in chapter two, I explicate Augustine’s own theory of perfection in order to provide an outline, and a basis of comparison, for Malebranche’s own theory of perfection. -

Time Atomism and Ash'arite Origins for Cartesian Occasionalism Revisited

Time Atomism and Ash‘arite Origins for Cartesian Occasionalism Revisited Richard T. W. Arthur Department of Philosophy McMaster University Hamilton, Ontario Canada Time Atomism and Ash’arite Origins for Occasionalism Revisited Introduction In gauging the contributions of Asian thinkers to the making of modern “Western” philosophy and science, one often encounters the difficulty of establishing a direct influence. Arun Bala and George Gheverghese Joseph (2007) have termed this “the transmission problem”. One can establish a precedence, as well as a strong probability that an influence occurred, without being able to find concrete evidence for it. In the face of this difficulty (which appears to occur quite generally in the history of thought) I suggest here that the influence of earlier thinkers does not always occur through one person reading others’ work and becoming persuaded by their arguments, but by people in given epistemic situations being constrained by certain historically and socially conditioned trends of thought—for which constraining and conditioned trends of thought I coin the term "epistemic vectors"—and opportunistically availing themselves of kindred views from other traditions. As a case in point, I will examine here the claim that the doctrine of Occasionalism arose in seventeenth century Europe as a result of an influence from Islamic theology. In particular, the Ash’arite school of kalâm presented occasionalism as a corollary of time atomism, and since to many scholars the seventeenth century occasionalism of Cartesian thinkers such as De la Forge and Cordemoy has appeared as a direct corollary of the atomism of time attributed to Descartes in his Meditations, Ash’arite time atomism is often cited as the likely source of Cartesian Occasionalism. -

Maurice-Quentin De La Tour

Neil Jeffares, Maurice-Quentin de La Tour Saint-Quentin 5.IX.1704–16/17.II.1788 This Essay is central to the La Tour fascicles in the online Dictionary which IV. CRITICAL FORTUNE 38 are indexed and introduced here. The work catalogue is divided into the IV.1 The vogue for pastel 38 following sections: IV.2 Responses to La Tour at the salons 38 • Part I: Autoportraits IV.3 Contemporary reputation 39 • Part II: Named sitters A–D IV.4 Posthumous reputation 39 • Part III: Named sitters E–L IV.5 Prices since 1800 42 • General references etc. 43 Part IV: Named sitters M–Q • Part V: Named sitters R–Z AURICE-QUENTIN DE LA TOUR was the most • Part VI: Unidentified sitters important pastellist of the eighteenth century. Follow the hyperlinks for other parts of this work available online: M Matisse bracketed him with Rembrandt among • Chronological table of documents relating to La Tour portraitists.1 “Célèbre par son talent & par son esprit”2 – • Contemporary biographies of La Tour known as an eccentric and wit as well as a genius, La Tour • Tropes in La Tour biographies had a keen sense of the importance of the great artist in • Besnard & Wildenstein concordance society which would shock no one today. But in terms of • Genealogy sheer technical bravura, it is difficult to envisage anything to match the enormous pastels of the président de Rieux J.46.2722 Contents of this essay or of Mme de Pompadour J.46.2541.3 The former, exhibited in the Salon of 1741, stunned the critics with its achievement: 3 I. -

The Philosophy of the Imagination in Vico and Malebranche

STRUMENTI PER LA DIDATTICA E LA RICERCA – 86 – Paolo Fabiani The Philosophy of the Imagination in Vico and Malebranche Translated and Edited by Giorgio Pinton Firenze University Press 2009 the philosophy of the imagination in Vico and male- branche / paolo Fabiani. – Firenze : Firenze university press, 2009. (strumenti per la didattica e la ricerca ; 86) http://digital.casalini.it/97864530680 isBn 978-88-6453-066-6 (print) isBn 978-88-6453-068-0 (online) immagine di copertina: © elenaray | dreamstime.com progetto grafico di alberto pizarro Fernández © 2009 Firenze university press università degli studi di Firenze Firenze university press Borgo albizi, 28, 50122 Firenze, italy http://www.fupress.com/ Printed in Italy “In memory of my mother ... to honor the courage of my father” Paolo Fabiani “This is more than my book, it also represents Giorgio Pinton’s interpretation of the imagi- nation in early modern philosophy. In several places of my work he felt obliged to simplify the arguments to easy the reading; he did it in agreement with me. In a few others, he substituted, with intelligence and without forcing, the structure of the original academic version in a differ- ent narrative organization of the contents. He has done a great job. It is an honor for me that the most important translator of Vico’s Latin Works into Eng- lish translated and edited my first philosophical essay. I heartly thank Giorgio Pinton, a true master of philosophy; Alexander Bertland, a very good scholar in Vico studies; and the editorial staff of FUP, expecially -

1 the Specter of Spinozism: Malebranche, Arnauld, Fénelon

The Specter of Spinozism: Malebranche, Arnauld, Fénelon What might a French Bishop, a German Lutheran polymath, two unorthodox Catholic priests—both French, one an Oratorian Cartesian in Paris and the other a Jansenist on the lam in the Spanish Low Countries—and a Huguenot exile in the Dutch Republic, all contemporaries in the second half of the seventeenth century, possibly have in common? The answer is not too difficult to find. François Fénelon, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Nicolas Malebranche, Antoine Arnauld and Pierre Bayle—like so many others in the period—all suffered from Spinozaphobia (although Bayle, at least, had some admiration for the “atheist” Spinoza’s virtuous life). Just as the specter of communism united Democrats and Republicans in the rough and tumble world of American politics in the 1940s and 50s, so the specter of Spinozism made room for strange bedfellows in the equally rough and tumble world of the early modern Republic of Letters. One of the topics which accounts for a good deal of the backlash against Spinoza, and which led some thinkers to accuse others of being—willingly or in spite of themselves—Spinozists, was the perceived materialism of Spinoza's theology. If one of the attributes of God is extension, as Spinoza claimed, then, it was argued by his critics, matter itself must belong to the essence of God, thereby making God material or body.1 And anyone whose philosophy even looks like it places extension or body (in whatever form) in God must be a Spinozist. Thus, Arnauld explicitly invokes Spinoza (a philosopher “who believed that the matter from which God made the world was uncreated”) as he insists that Malebranche's claim, in the Vision in God doctrine, that something called "intelligible extension" is in God—which is why we are able to cognize 1 material bodies by apprehending their ideas or intelligible archtypes in God—is tantamout to making God Himself extended.2 Arnauld was certainly not alone in claiming that Malebranche’s theory of “intelligible extension” implies a kind of Spinozism. -

| 216.302.8404 “An Early Music Group with an Avant-Garde Appetite.” — the New York Times

“CONCERTS AND RECORDINGS“ BY LES DÉLICES ARE JOURNEYS OF DISCOVERY.” — NEW YORK TIMES www.lesdelices.org | 216.302.8404 “AN EARLY MUSIC GROUP WITH AN AVANT-GARDE APPETITE.” — THE NEW YORK TIMES “FOR SHEER STYLE AND TECHNIQUE, LES DÉLICES REMAINS ONE OF THE FINEST BAROQUE ENSEMBLES AROUND TODAY.” — FANFARE “THE MEMBERS OF LES DÉLICES ARE FIRST CLASS MUSICIANS, THE ENSEMBLE Les Délices (pronounced Lay day-lease) explores the dramatic potential PLAYING IS IRREPROACHABLE, AND THE and emotional resonance of long-forgotten music. Founded by QUALITY OF THE PIECES IS THE VERY baroque oboist Debra Nagy in 2009, Les Délices has established a FINEST.” reputation for their unique programs that are “thematically concise, — EARLY MUSIC AMERICA MAGAZINE richly expressive, and featuring composers few people have heard of ” (NYTimes). The group’s debut CD was named one of the "Top “DARING PROGRAMMING, PRESENTED Ten Early Music Discoveries of 2009" (NPR's Harmonia), and their BOTH WITH CONVICTION AND MASTERY.” performances have been called "a beguiling experience" (Cleveland — CLEVELANDCLASSICAL.COM Plain Dealer), "astonishing" (ClevelandClassical.com), and "first class" (Early Music America Magazine). Since their sold-out New “THE CENTURIES ROLL AWAY WHEN York debut at the Frick Collection, highlights of Les Délices’ touring THE MEMBERS OF LES DÉLICES BRING activites include Music Before 1800, Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner THIS LONG-EXISTING MUSIC TO Museum, San Francisco Early Music Society, the Yale Collection of COMMUNICATIVE AND SPARKLING LIFE.” Musical Instruments, and Columbia University’s Miller Theater. Les — CLASSICAL SOURCE (UK) Délices also presents its own annual four-concert series in Cleveland art galleries and at Plymouth Church in Shaker Heights, OH, where the group is Artist in Residence.