Being, Moving, and Enforcing Justice in the City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Icons of Survival: Metahumanism As Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 169–196. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 20:32 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense In which I argue that superhero comics, the most maligned of nerd genres, theorize the transformation of ethics and politics necessary to the project of planetary defense. The figure of the “metahuman,” the human with superpowers and purpose, embodies the transfigured nerd whose defects—intellect, swarm-behavior, abnormality, flux, and love of machines—become virtues of survival in the twenty-first century. The conflict among capitalism, fascism, and communism, which drove the Cold War and its immediate aftermath, also drove the Golden and Silver Ages of Comics. In the era of planetary emergency, these forces reconfigure themselves as different versions of world-destruction. The metahuman also signifies going “beyond” these economic and political systems into orders that preserve democracy without destroying the biosphere. Therefore, the styles of metahuman figuration represent an appeal to tradition and a technique of transformation. I call these strategies the iconic style and metamorphic style. The iconic style, more typical of DC Comics, makes the hero an icon of virtue, and metahuman powers manifest as visible signs: the “S” of Superman, the tiara and golden lasso of Wonder Woman. -

Batman’S Story

KNI_T_01_p01 CS6.indd 1 10/09/2020 10:14 IN THIS ISSUE YOUR PIECE Meet your white king – the latest 3 incarnation of the World’s Greatest Detective, the Dark Knight himself. PROFILE From orphan to hero, from injury 4 to resurrection; this is Batman’s story. GOTHAM GUIDE Insights into the Batman’s sanctum and 10 operational centre, a place of history, hi-tech devices and secrets. RANK & FILE Why the Dark Knight of Gotham is a 12 king – his knowledge, assessments and regal strategies. RULES & MOVES An indispensable summary of a king’s 15 mobility and value, and a standard move. Editor: Simon Breed Thanks to: Art Editor: Gary Gilbert Writers: Frank Miller, David Mazzucchelli, Writer: Alan Cowsill Grant Morrison, Jeph Loeb, Dennis O’Neil. Consultant: Richard Jackson Pencillers: Brett Booth, Ben Oliver, Marcus Figurine Sculptor: Imagika Sculpting To, Adam Hughes, Jesus Saiz, Jim Lee, Studio Ltd Cliff Richards, Mark Bagley, Lee Garbett, Stephane Roux, Frank Quitely, Nicola US CUSTOMER SERVICES Scott, Paulo Siqueira, Ramon Bachs, Tony Call: +1 800 261 6898 Daniel, Pete Woods, Fernando Pasarin, J.H. Email: [email protected] Williams III, Cully Hamner, Andy Kubert, Jim Aparo, Cameron Stewart, Frazer Irving, Tim UK CUSTOMER SERVICES Sale, Yanick Paquette, Neal Adams. Call: +44 (0) 191 490 6421 Inkers: Rob Hunter, Jonathan Glapion, J.G. Email: [email protected] Jones, Robin Riggs, John Stanisci, Sandu Florea, Tom Derenick, Jay Leisten, Scott Batman created by Bob Kane Williams, Jesse Delperdang, Dick Giordano, with Bill Finger Chris Sprouse, Michel Lacombe. Copyright © 2020 DC Comics. BATMAN and all related characters and elements © and TM DC Comics. -

X-Men: Age of Apocalypse Prelude Free

FREE X-MEN: AGE OF APOCALYPSE PRELUDE PDF Scott Lobdell,Jeph Loeb,Mark Waid | 264 pages | 01 Jun 2011 | Marvel Comics | 9780785155089 | English | New York, United States X-Men: Prelude to Age of Apocalypse by Scott Lobdell The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its X-Men: Age of Apocalypse Prelude packaging where packaging is applicable. Packaging should be the same as what is found in a retail store, unless the item is handmade or was packaged by the manufacturer in non-retail packaging, such as an unprinted box or plastic bag. See details for additional description. Skip to main content. About this product. New other. Make an offer:. Auction: New Other. Stock photo. Brand new: Lowest price The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Buy It Now. Add X-Men: Age of Apocalypse Prelude cart. Make Offer. Condition is Brand New. See all 3 brand new listings. About this product Product Information Legion, the supremely powerful son of Charles Xavier, wants to change the world, and he's travelled back in time to kill Magneto to do it Can the X-Men stop him, or will the world as we know it cease to exist? Additional Product Features Dewey Edition. Show X-Men: Age of Apocalypse Prelude Show Less. Add to Cart. Any Condition Any Condition. See all 13 - All listings for this product. Ratings and Reviews Write a review. Most relevant reviews. Thanks Thanks Verified purchase: Yes. Suess Beginners Book Collection by Dr. SuessHardcover 4. -

Bibliografia Di Bob Harras

BIBLIOGRAFIA DI BOB HARRAS A cura di: Gabriele 'Termidoro' Perlini - mail: [email protected] Prima stesura: gennaio 2021 THE AVENGERS vol. I (serie di 402, 1963-1996) MARVEL C&V#64, #280 Faithful Servant Bob Harras Bob Hall & Kyle Baker Kyle Baker MO115 The Collection Obsession - Part One: #334 Bob Harras Andy Kubert Tom Palmer Sr. VEN#9 First Encounter The Collection Obsession - Part Two: Tom Palmer Sr. & Bob Harras Jeff Moore VEN#9 #335 Bloody Encounter Tony DeZuniga Collect And Proceed (9 pag.) Bob Harras Steve Epting Tom Palmer Sr. VEN#9 The Collection Obsession - Part Three: #336 Bob Harras Steve Epting Tom Palmer Sr. VEN#9 For Here We Make Our Stand! The Collection Obsession - Part For: #337 Bob Harras Steve Epting Tom Palmer Sr. VEN#10 Mud And Glory? The Collection Obsession - Part Five: #338 Bob Harras Steve Epting Tom Palmer Sr. VEN#10 Infectious Compulsions The Collection Obsession - Part Six: #339 Bob Harras Steve Epting Tom Palmer Sr. VEN#10 Final Redemption VEN#12, #343 First Night Bob Harras Steve Epting Tom Palmer Sr. MH40 VEN#12, #344 Echoes Of The Past Bob Harras Steve Epting Tom Palmer Sr. MH40 AAC#51, Operation: Galactic Storm - Part Five: #345 Bob Harras Steve Epting Tom Palmer Sr. MC#2, Storm Warnings(*) GE14 Operation: Galactic Storm - Part MC#3, #346 Bob Harras Steve Epting Tom Palmer Sr. Twelve: Assassination(*) GE14 Operation: Galactic Storm - Part MC#5, #347 Bob Harras Steve Epting Tom Palmer Sr. Nineteen: Empire's End(*) GE15 VEN#13, #348 Familial Connections Bob Harras Kirk Jarvinen Tom Palmer Sr. -

Dc Entertainment Feb20 0392 Joker 80Th Anniv 100 Page Super Spect #1 $9.99 Feb20 0393 Joker 80Th Anni

DC ENTERTAINMENT FEB20 0392 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 $9.99 FEB20 0393 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1940S ARTHUR ADAMS VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0394 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1950S DAVID FINCH VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0395 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1960S F MATTINA VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0396 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1970S JIM LEE VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0397 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1980S SEINKIEWICZ VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0398 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1990S G DELLOTTO VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0399 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 2000S LEE BERMEJO VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0400 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 2010S JOCK VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0401 JOKER 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 BLANK VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0402 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 $9.99 FEB20 0403 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1940S ADAM HUGHES VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0404 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1950S TRAVIS CHAREST VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0405 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1960S STANLEY LAU VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0406 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1970S FRANK CHO VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0407 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1980S J SCOTT CAMPBELL VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0408 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 1990S GABRIELLE DELL OTTO VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0409 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 2000S JIM LEE VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 0410 CATWOMAN 80TH ANNIV 100 PAGE SUPER SPECT #1 2010S JEEHYUNG LEE VAR ED $9.99 FEB20 -

ARCHIE COMICS Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012

ARCHIE COMICS Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012 Archie Comics Archie Meets KISS Summary: A highly unexpected pairing leads to a very Alex Segura, Dan Parent fun title that everyone’s talking about. Designed for both 9781936975044 KISS’s and Archie’s legions of fans and backed by Pub Date: 5/1/12 (US, Can.), On Sale Date: 5/1 massive publicity including promotion involving KISS $12.99/$14.99 Can. cofounders Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley, Archie 112 pages expects this title to be a breakout success. Paperback / softback / Trade paperback (US) Comics & Graphic Novels / Fantasy From the the company that’s sold over 1 billion comic books Ctn Qty: 0 and the band that’s sold over 100 million albums and DVDs 0.8lb Wt comes this monumental crossover hit! Immortal rock icons 363g Wt KISS join forces ... Author Bio: Alex Segura is a comic book writer, novelist and musician. Alex has worked in comics for over a decade. Before coming to Archie, Alex served as Publicity Manager at DC Comics. Alex has also worked at Wizard Magazine, The Miami Herald, Newsarama.com and various other outlets and websites. Author Residence: New York, NY Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012 Archie Comics Archie Meets KISS: Collector's Edition Summary: A highly unexpected pairing leads to a very Alex Segura, Dan Parent, Gene Simmons fun title that everyone’s talking about. Designed for both 9781936975143 KISS’s and Archie’s legions of fans and backed by Pub Date: 5/1/12 (US, Can.), On Sale Date: 5/1 massive publicity including promotion involving KISS $29.99/$34.00 Can. -

Rationale for Magneto: Testament Brian Kelley

SANE journal: Sequential Art Narrative in Education Volume 1 Article 7 Issue 1 Comics in the Contact Zone 1-1-2010 Rationale For Magneto: Testament Brian Kelley Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sane Part of the American Literature Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Art Education Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Educational Psychology Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Higher Education Commons, Illustration Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kelley, Brian (2010) "Rationale For Magneto: Testament," SANE journal: Sequential Art Narrative in Education: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 7. Available at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sane/vol1/iss1/7 This Rationale is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in SANE journal: Sequential Art Narrative in Education by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Kelley: Rationale For Magneto: Testament 1:1_______________________________________r7 X-Men: Magneto Testament (2009) By Gregory Pak and Carmine Di Giandomenico Rationale by Brian Kelley Grade Level and Audience This graphic novel is recommended for middle and high school English and social studies classes. Plot Summary Before there was the complex X-Men villain Mangeto, there was Max Eisenhardt. As a boy, Max has a loving family: a father who tinkers with jewelry, an overprotective mother, a sickly sister, and an uncle determined to teach him how to be a ladies’ man. -

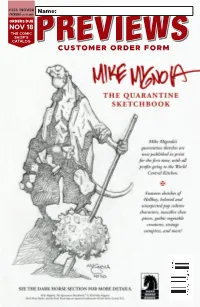

Customer Order Form

#386 | NOV20 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Nov20 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:23:12 AM Nov20 Ad DST Rogue.indd 1 10/8/2020 11:07:39 AM PREMIER COMICS HAHA #1 IMAGE COMICS 30 RAIN LIKE HAMMERS #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 CRIMSON FLOWER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 62 AVATAR: THE NEXT SHADOW #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 64 MARVEL ACTION: CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING 104 KING IN BLACK: BLACK KNIGHT #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-6 RED SONJA: THE SUPER POWERS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 126 ABBOTT: 1973 #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 158 Nov20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:24:32 AM COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE FEATURED ITEMS Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS I Breathed A Body #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS 1 Delicates TP l ONI PRESS l I Breathed A Body #1 AFTERSHOCK COMICS 1 The Cutting Edge: Devil’s Mirror #1 l TITAN COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS Knights of Heliopolis HC l TITAN COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Blade Runner 2029 #2 l TITAN COMICS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars Insider #200 l TITAN COMICS Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Comic Book Creator #25 l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Bloodshot #9 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Vagrant Queen Volume 2: A Planet Called Doom TP l VAULT COMICS Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. -

New Avengers: Volume 1 Ebook

NEW AVENGERS: VOLUME 1 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Brian Bendis,Stuart Immonen | 160 pages | 27 Jul 2011 | Marvel Comics | 9780785148739 | English | New York, United States New Avengers: Volume 1 PDF Book Avengers 4 "Captain America Joins Avengers "The Taking of the Avengers! Frank D'Armata Illustrator. Avengers "Duty Over All! This volume is a slightly weak 4 stars, but it's surely better than Marc Waid's All-New Avengers and is at least comparable with Gerry Duggan's Uncanny Avengers , so I'm happy with it as a start. Time will tell if Bendis can sustain such high quality on two titles that are essentially the same -- for the time being the Avengers and New Avengers books are a smashing success, as is "The Heroic Age. Strange, strangely enough. This was a very enjoyable read. As a result, Doctor Strange subsequently regains his position of Sorcerer Supreme. Avengers "Thieves Honor" Cover date: January , Avengers "On the Matter of Heroes! Here, a couple of that book's cast White Tiger and Power Man join up with an assortment of other heroes from Squirrel Girl to Hawkeye for a series that's all about crazy science and weird extradimensional business from the get-go. First in Series. It's half the whole reason the Avengers movie made a gajillion dollars. Sep 03, Sam Quixote rated it did not like it. Because most of the people who really love Joss Whedon really enjoy how his characters constantly quip. But as a first volume, this made me very happy indeed. The first two were written by Brian Michael Bendis and depicted a version of Marvel's premiere superhero team, the Avengers. -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Mason 2015 02Thesis.Pdf (1.969Mb)

‘Page 1, Panel 1…” Creating an Australian Comic Book Series Author Mason, Paul James Published 2015 Thesis Type Thesis (Professional Doctorate) School Queensland College of Art DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3741 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367413 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au ‘Page 1, Panel 1…” Creating an Australian Comic Book Series Paul James Mason s2585694 Bachelor of Arts/Fine Art Major Bachelor of Animation with First Class Honours Queensland College of Art Arts, Education and Law Group Griffith University Submitted in fulfillment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Visual Arts (DVA) June 2014 Abstract: What methods do writers and illustrators use to visually approach the comic book page in an American Superhero form that can be adapted to create a professional and engaging Australian hero comic? The purpose of this research is to adapt the approaches used by prominent and influential writers and artists in the American superhero/action comic-book field to create an engaging Australian hero comic book. Further, the aim of this thesis is to bridge the gap between the lack of academic writing on the professional practice of the Australian comic industry. In order to achieve this, I explored and learned the methods these prominent and professional US writers and artists use. Compared to the American industry, the creating of comic books in Australia has rarely been documented, particularly in a formal capacity or from a contemporary perspective. The process I used was to navigate through the research and studio practice from the perspective of a solo artist with an interest to learn, and to develop into an artist with a firmer understanding of not only the medium being engaged, but the context in which the medium is being created. -

Or Live Online Via Proxibid! Follow Us on Facebook and Twitter @Back2past for Updates

2/12 Well-Loved: Comic Books, Star Trek Toys, & More 2/12/2020 This session will be held at 6PM, so join us in the showroom (35045 Plymouth Road, Livonia MI 48150) or live online via Proxibid! Follow us on Facebook and Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! (Showroom Terms: No buyer's premium!) Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast (See site for terms) LOT # LOT # 1 Auctioneer Announcements 10a Star Trek Action Figure Lot Upcoming events, rules and regulations, etc and so Large lot of figures. You get all pictured. Nice shape. forth. 11 Group of (5) Copper/Modern Notable Books 2 Solar Man of the Atom #1 CGC 9.2/Key Neat group of mixed Copper to Modern age books. 1st appearance of Solar, Man of the Atom. CGC May include Marvel, DC and Indy semi-key books or graded comic. classic/variant covers. Most in NM condition. Please 3 Wonder Woman 2007 (1-5) inspect photos. You get all that is pictured. NM run. 12 Batman Prestige Format Group of (5) 4 Group of (5) Copper/Modern Notable Books You get all that is pictured in NM condition. Neat group of mixed Copper to Modern age books. 13 Super Powers (1984) Mini-Series Set 1-5 May include Marvel, DC and Indy semi-key books or VF/VF+ condition. classic/variant covers. Most in NM condition. Please 14 Group of (5) Copper/Modern Notable Books inspect photos.