Valentino Book4cd.Pdf (3.033Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

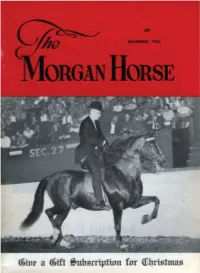

Iur a ~If T ~Uhsrriptinn Fnr Ql4ristmas O4ppleuale O4duenturer 13958

~iur a ~if t ~uhsrriptinn fnr Ql4ristmas_ o4ppLeuaLe o4duenturer 13958 Congratulations to Mr. Robert Morgan of San Jose, California on his selection of Applevale Ad venturer, an outstanding yearling stallion by Pecos 8969 out of Mar issa 09162. VOORHIS FARM Home of Applevale Morgans Red Hook, Dutchess Co., New York. MR. and MRS. GORDON VOORHIS, owners FRED HERRICK, trainer Tel. Plateau 8-56 l l Tel. Plateau 8-3283 BHDJlDWHll f JlH JJ] MEG FERGUSON, 13, WITH HER GELDING BROADWALL COMMANDER 11887. I (Parade 10138 - Texas Lyn 05818) Meg rides Broadwa ll Commander (Red) on the fifty mile pleasure ride and a lso shows him. '· We have three wean ling fil lies by Parade and Broadwall Drum Major and some goo d sta lli on and geldi ng pr ospects . VISIT US BEFOREBUYING. Mr. and Mrs. J. Cecil Ferguson Broadwall Farm Greene, Rhode Island EXPRESS7-3963 SPECIALFEATURES :Eastern Stale& Horse Show . 6 So It's Time To Register Your Foal . 11 Three Morgana Participate In 17th Annual VI.ala-Palomar Ride 13 The 1963 llllnola State Fair . 15 Versatillty Show Draws Entries from Seven States . 16 2nd and 3rd Place Winner Verse Contest . 16 Circle J Show Results . 48 Dear Sir : [ am enclosing $4.00 for a subscrip REGULAR FEATURES tion for our local library. This might Letters to the Editor . 4 be a thought for oth ers to do, especially The Prasident's Comer . 5 Horses. Horses, Horses . 9 if several people went together, the Jes· Hossin' Around . 12 co.st would be nominal and might help Mid-States Morgan Club . -

Boris Pasternak - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Boris Pasternak - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Boris Pasternak(10 February 1890 - 30 May 1960) Boris Leonidovich Pasternak was a Russian language poet, novelist, and literary translator. In his native Russia, Pasternak's anthology My Sister Life, is one of the most influential collections ever published in the Russian language. Furthermore, Pasternak's theatrical translations of Goethe, Schiller, Pedro Calderón de la Barca, and William Shakespeare remain deeply popular with Russian audiences. Outside Russia, Pasternak is best known for authoring Doctor Zhivago, a novel which spans the last years of Czarist Russia and the earliest days of the Soviet Union. Banned in the USSR, Doctor Zhivago was smuggled to Milan and published in 1957. Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature the following year, an event which both humiliated and enraged the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In the midst of a massive campaign against him by both the KGB and the Union of Soviet Writers, Pasternak reluctantly agreed to decline the Prize. In his resignation letter to the Nobel Committee, Pasternak stated the reaction of the Soviet State was the only reason for his decision. By the time of his death from lung cancer in 1960, the campaign against Pasternak had severely damaged the international credibility of the U.S.S.R. He remains a major figure in Russian literature to this day. Furthermore, tactics pioneered by Pasternak were later continued, expanded, and refined by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and other Soviet dissidents. <b>Early Life</b> Pasternak was born in Moscow on 10 February, (Gregorian), 1890 (Julian 29 January) into a wealthy Russian Jewish family which had been received into the Russian Orthodox Church. -

Animals Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 2

AAnniimmaallss LLiibbeerraattiioonn PPhhiilloossoopphhyy aanndd PPoolliiccyy JJoouurrnnaall VVoolluummee 55,, IIssssuuee 22 -- 22000077 Animal Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 2 2007 Edited By: Steven Best, Chief Editor ____________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Lev Tolstoy and the Freedom to Choose One’s Own Path Andrea Rossing McDowell Pg. 2-28 Jewish Ethics and Nonhuman Animals Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 29-47 Deliberative Democracy, Direct Action, and Animal Advocacy Stephen D’Arcy Pg. 48-63 Should Anti-Vivisectionists Boycott Animal-Tested Medicines? Katherine Perlo Pg. 64-78 A Note on Pedagogy: Humane Education Making a Difference Piers Bierne and Meena Alagappan Pg. 79-94 BOOK REVIEWS _________________ Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal, by Eric Schlosser (2005) Reviewed by Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 95-101 Eternal Treblinka: Our Treatment of Animals and the Holocaust, by Charles Patterson (2002) Reviewed by Steven Best Pg. 102-118 The Longest Struggle: Animal Advocacy from Pythagoras to PETA, by Norm Phelps (2007) Reviewed by Steven Best Pg. 119-130 Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Volume V, Issue 2, 2007 Lev Tolstoy and the Freedom to Choose One’s Own Path Andrea Rossing McDowell, PhD It is difficult to be sat on all day, every day, by some other creature, without forming an opinion about them. On the other hand, it is perfectly possible to sit all day every day, on top of another creature and not have the slightest thought about them whatsoever. -- Douglas Adams, Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency (1988) Committed to the idea that the lives of humans and animals are inextricably linked, Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy (1828–1910) promoted—through literature, essays, and letters—the animal world as another venue in which to practice concern and kindness, consequently leading to more peaceful, consonant human relations. -

Dvigubski Full Dissertation

The Figured Author: Authorial Cameos in Post-Romantic Russian Literature Anna Dvigubski Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Anna Dvigubski All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Figured Author: Authorial Cameos in Post-Romantic Russian Literature Anna Dvigubski This dissertation examines representations of authorship in Russian literature from a number of perspectives, including the specific Russian cultural context as well as the broader discourses of romanticism, autobiography, and narrative theory. My main focus is a narrative device I call “the figured author,” that is, a background character in whom the reader may recognize the author of the work. I analyze the significance of the figured author in the works of several Russian nineteenth- and twentieth- century authors in an attempt to understand the influence of culture and literary tradition on the way Russian writers view and portray authorship and the self. The four chapters of my dissertation analyze the significance of the figured author in the following works: 1) Pushkin's Eugene Onegin and Gogol's Dead Souls; 2) Chekhov's “Ariadna”; 3) Bulgakov's “Morphine”; 4) Nabokov's The Gift. In the Conclusion, I offer brief readings of Kharms’s “The Old Woman” and “A Fairy Tale” and Zoshchenko’s Youth Restored. One feature in particular stands out when examining these works in the Russian context: from Pushkin to Nabokov and Kharms, the “I” of the figured author gradually recedes further into the margins of narrative, until this figure becomes a third-person presence, a “he.” Such a deflation of the authorial “I” can be seen as symptomatic of the heightened self-consciousness of Russian culture, and its literature in particular. -

POP Library SUBJECT LIST 12/11/2010

POP Library SUBJECT LIST 12/11/2010 Subject Title Author Location Addictions Narcotics Anonymous World Service 613.8 Ser Adolescents The Secret Survival Manual J.Brent Bill J 155.5 Bil Group Growers Lane Eskew 155.5 Esk Help! I'm A Volunteer Youth Worker! Doug Fields 155.5 Fie Group's Best Jr. High Meetings Cindy Parolini 155.5 Par Adult Education Llifelong Learning Rebecca Grothe 374 Gro Starting Small Groups - And Keeping Them George S Johnson 374 Joh Advent The Jesse Tree Anderson, Raymond And Georgene 263 And Jesse Tree Devotions Marilyn Breckenridge 263 Bre Unto Us Is Born Herbert Brookering 242 Bro Unto Us Is Born Herbert F. Brookering 242.2 Bro Prepare Ye For A New Advent Of God's Love John And Adrian Carr 263 Car The Comings Of God Richard Simon Hanson 263 Han Advent Landmarks Robert Hershey 263 Her Advent Paul M. Lindberg 263 Lin What Child Is This? Samuel H. Miller 263 Mil Won't You Let Him In? James W. Moore 242.3 Mor Family Countdown To Christmas Debbie Trafton O'Neal 263 O'Ne Celebrate Jesus At Christmas Kimberly Ingalls Reese 394 Ree Lighted Windows Margaret Silf 263 Sil Countdown To Christmas Zimmerman, Laura K. E. 263 Zim Advent / Christmas Destination Bethlehem Ann W. Anderson 263 And Come Lord Jesus Susan Briehl 242 Bri Day By Day In Advent Christopher G. Milarch 242 Mil Manger In The Mountains James Arne Nestingen 242 Nes Age Groups New Passages Gail Sheehy 305.2 She Aging Coming Of Age Gracefully Aid Association For Lutherans 155.7 AAL Home Sweet Home Aid Association For Lutherans 362.6 Hom Fullness Of Time Martha Whitmore Hickman 155.6 Hic Caring For Aging Parents Richard P. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Tolstoy and Cosmopolitanism

CHAPTER 8 Tolstoy and Cosmopolitanism Christian Bartolf Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) is known as the famous Russian writer, author of the novels Anna Karenina, War and Peace, The Kreutzer Sonata, and Resurrection, author of short prose like “The Death of Ivan Ilyich”, “How Much Land Does a Man Need”, and “Strider” (Kholstomer). His literary work, including his diaries, letters and plays, has become an integral part of world literature. Meanwhile, more and more readers have come to understand that Leo Tolstoy was a unique social thinker of universal importance, a nineteenth- and twentieth-century giant whose impact on world history remains to be reassessed. His critics, descendants, and followers became almost innu- merable, among them Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi in South Africa, later called “Mahatma Gandhi”, and his German-Jewish architect friend Hermann Kallenbach, who visited the publishers and translators of Tolstoy in England and Scotland (Aylmer Maude, Charles William Daniel, Isabella Fyvie Mayo) during the Satyagraha struggle of emancipation in South Africa. The friendship of Gandhi, Kallenbach, and Tolstoy resulted in an English-language correspondence which we find in the Collected Works C. Bartolf (*) Gandhi Information Center - Research and Education for Nonviolence (Society for Peace Education), Berlin, Germany © The Author(s) 2018 121 A.K. Giri (ed.), Beyond Cosmopolitanism, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-5376-4_8 122 C. BARTOLF of both, Gandhi and Tolstoy, and in the Tolstoy Farm as the name of the second settlement project of Gandhi -

Economies of Russian Literature 1830-1850 by Jillian

Money and Mad Ambition: Economies of Russian Literature 1830-1850 By Jillian Elizabeth Porter A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Harsha Ram, chair Professor Irina Paperno Professor Luba Golburt Professor Victoria Bonnell Spring 2011 Money and Mad Ambition: Economies of Russian Literature 1830-1850 © 2011 by Jillian Elizabeth Porter 1 Abstract Money and Mad Ambition: Economies of Russian Literature 1830-1850 by Jillian Elizabeth Porter Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor Harsha Ram, chair This dissertation offers a sustained examination of the economic paradigms that structure meaning and narrative in Russian literature of the 1830s-1840s, the formative years of nineteenth-century Russian prose. Exploring works by Alexander Pushkin, Nikolai Gogol, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Faddei Bulgarin, I view tropes such as spending, counterfeiting, hoarding, and gambling, as well as plots of mad or blocked ambition, in relation to the cultural and economic history of Nicholas I’s reign and in the context of the importation of economic discourse and literary conventions from abroad. Furthermore, I consider the impact of culturally and economically conditioned affects—ambition, avarice, and embarrassment—on narrative tone. From the post-Revolutionary French plot of social ambition to -

2018 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 FIRST RUNNING the First Running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park Took Place on a Thursday

2018 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 FIRST RUNNING The first running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park took place on a Thursday. The race was 1 5/8 miles long and the conditions included “$200 each; half forfeit, and $1,500-added. The second to receive $300, and an English racing saddle, made by Merry, of St. James TABLE OF Street, London, to be presented by Mr. Duncan.” OLDEST TRIPLE CROWN EVENT CONTENTS The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is the oldest of the Triple Crown events. It predates the Preakness Stakes (first run in 1873) by six years and the Kentucky Derby (first run in 1875) by eight. Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby, ran second in the 1875 Belmont behind winner Calvin. RECORDS AND TRADITIONS . 4 Preakness-Belmont Double . 9 FOURTH OLDEST IN NORTH AMERICA Oldest Triple Crown Race and Other Historical Events. 4 Belmont Stakes Tripped Up 19 Who Tried for Triple Crown . 9 The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is one of the oldest stakes races in North America. The Phoenix Stakes at Keeneland was Lowest/Highest Purses . .4 How Kentucky Derby/Preakness Winners Ran in the Belmont. .10 first run in 1831, the Queens Plate in Canada had its inaugural in 1860, and the Travers started at Saratoga in 1864. However, the Belmont, Smallest Winning Margins . 5 RUNNERS . .11 which will be run for the 150th time in 2018, is third to the Phoenix (166th running in 2018) and Queen’s Plate (159th running in 2018) in Largest Winning Margins . -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

Wings Five Evenings Flying Asleep and Awake Beware of the Car Walking the Streets of Moscow

2014 AMHERST COLLEGE RUSSIAN DEPARTMENT GOOD OLD SOVIET CLASSICS WITH ENGLISH SUBTITLES. STIRN AUDITORIUM, AMHERST COLLEGE, 7 PM. SPRING Flying Asleep and Five evenings Th 1979 Awake Wings 4/17 1982 1966 Nikita Mikhalkov Fr Beware of the Car Fr 4/25 3/28 Roman Balayan Walking the Streets of Fr 1966 Larisa Shepitko The tangible world of an old 2/21 Eldar Ryazanov communal apartment in Moscow It is a tragicomedy about a man Moscow 1963 It is a fascinating and human Fr of the 1950’s is recreated who is in no way aggressive or 3/7 portrayal of a once-famous Georgiy Daneliya A comedy film noir about Soviet Robin Hood onscreen with an incredible embittered, but nothing makes fighter pilot and loyal Stalinist In this charming lyrical comedy, which also - a modest insurance agent who in his spare accuracy, capturing the flair of the him happy: his loving wife, his named Nadezhda Petrovna. appears as an unofficial tourist guide of the time - is engaged in theft of private cars of time. Alexander and Tamara, who young mistress, friends, or job. Now a 41-year-old provincial Russian capital, a young writer from Siberia major criminals. He sells the stolen cars and loved each other before the war He just cannot find a place where schoolmistress, she has so comes to Moscow and makes new friends. anonymously transfers the money to the separated them, meet here after he "belongs", and often acts like a internalized the military ideas Russian youngsters of the sixties emerge as the accounts of various orphanages. -

Sarah's Diss Revised

UNNERVING IMAGES: CINEMATIC REPRESENTATIONS OF ANIMAL SLAUGHTER AND THE ETHICS OF SHOCK by Sarah Jane O’Brien A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of The Centre for Comparative Literature University of Toronto © Copyright by Sarah Jane O’Brien (2012) —Abstract— UNNERVING IMAGES: CINEMATIC REPRESENTATIONS OF ANIMAL SLAUGHTER AND THE ETHICS OF SHOCK Sarah Jane O’Brien Doctor of Philosophy, 2012 The Centre for Comparative Literature University of Toronto This dissertation forges critical connections between the industrial logic of cutting up animals to make meat and cinematic techniques of cutting up indexical images of animals to create spectacle. I begin by identifying the cinematic attraction of violent animal death. In Chapter One, I argue that social and material conditions prevent cinema from representing real (i.e., unsimulated) human death, and the medium in turn relies on animal bodies to register visible evidence of death. I contend that this displacement does not yield the definitive knowledge of death that it promises; reviewing scenes of animal death, we acquire no real knowledge of the “fact” of death, but rather approach an understanding that we share death—finitude, vulnerability, suffering—with animals. Cinema’s ethical potential rests on its singular capacity to lay bare this shared susceptibility, and I thus shift my attention to evaluating how seminal scenes of animal slaughter and fundamental techniques of film form fulfil or fail this ethical potential. I begin my wide-ranging analysis by identifying and critiquing, in Chapter Two, the methods of exposure that currently dominate cinematic representations of slaughter.