Hard, Hard Religion: the Invisible Institution of the New South

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROPERTY of Gnmdy Cotulty Historical Society P.O

,,~,: t 4""6 : /: 1'-: ,. 0, r 1:. THE HILL FAMILY OF BEERSHEBA SPRINGS. TENNESSEE Prepared by Ralph H. Willis and Mrs. Delbert (Kaye) Denton The Ben Hill family that has ,lived in Beersheba since the early 1900s can trace and document its ancestry for six generations to the elder Hill who was one of the earlier settlers of this part of Tennessee. Prior to this, the roots of the Hill family can be traced back to Hancock and Jasper counties in Georgia; thence to Edgecombe County (formerly part of Martin County), North Carolina, thence to St. Mary's, Charles County. Maryland, thence to Charlestown, Massachusetts, thence to England. In attempting to summ~rize the history of this family. we list first the direct line of descent. Secondly, we detail the families of those in the direct liqe. This is followed by brief descriptions of the women and that of·their families who married into the direct line. We conclude with biographical information which will show something more about som)!-'of those in the direct line of descent . Our clearly docum~ed history begins with Isaac Hilt. Sr .• who' was born and raised in St. Mary's, Charles County, Maryland. He was born 22 July 1748 and married Lucinda Wallace who was also born arid raised in St. Mary's; her date of birth being 1746. Isaac and Lucinda were married in 1773 and their first child. was born 7 February. 1774. Here follows the direct line: ... - ISAAC 'HILL, SR. - Born. 22 July 1748, Died 28 July 1825 Married: (1) Lucinda Wallace (Born 1746. -

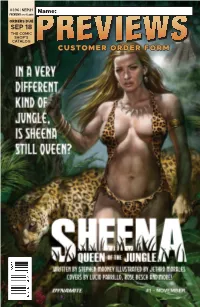

Customer Order Form

#396 | SEP21 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE SEP 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Sep21 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:51 AM GTM_Previews_ROF.indd 1 8/5/2021 8:54:18 AM PREMIER COMICS NEWBURN #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 A THING CALLED TRUTH #1 IMAGE COMICS 38 JOY OPERATIONS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 84 HELLBOY: THE BONES OF GIANTS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 86 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG: IMPOSTER SYNDROME #1 IDW PUBLISHING 114 SHEENA, QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 132 POWER RANGERS UNIVERSE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 184 HULK #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-4 Sep21 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:11 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Guillem March’s Laura #1 l ABLAZE The Heathens #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Fathom: The Core #1 l ASPEN COMICS Watch Dogs: Legion #1 l BEHEMOTH ENTERTAINMENT 1 Tuki Volume 1 GN l CARTOON BOOKS Mutiny Magazine #1 l FAIRSQUARE COMICS Lure HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 The Overstreet Guide to Lost Universes SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Carbon & Silicon l MAGNETIC PRESS Petrograd TP l ONI PRESS Dreadnoughts: Breaking Ground TP l REBELLION / 2000AD Doctor Who: Empire of the Wolf #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2029 #9 l TITAN COMICS The Man Who Shot Chris Kyle: An American Legend HC l TITAN COMICS Star Trek Explorer Magazine #1 l TITAN COMICS John Severin: Two-Fisted Comic Book Artist HC l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING The Harbinger #2 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Lunar Room #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 My Hero Academia: Ultra Analysis Character Guide SC l VIZ MEDIA Aidalro Illustrations: Toilet-Bound Hanako Kun Ark Book SC l YEN PRESS Rent-A-(Really Shy!)-Girlfriend Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Lupin III (Lupin The 3rd): Greatest Heists--The Classic Manga Collection HC l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT APPAREL 2 Halloween: “Can’t Kill the Boogeyman” T-Shirt l HORROR Trese Vol. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Chelan County Public Utility District #1 Seeks An

Klickitat County Public Utility District No. 1 seeks an accomplished, strategic leader to serve as its… Chief Financial Officer/ Chief Risk Officer Strategic financial planning and sound financial management is critical to successfully managing a complex utility in today’s environment, and balancing risk provides insights that allow Klickitat County PUD to be a premier public utility. Join our respected public utility in this opportunity to provide executive leadership in all financial areas and risk management, including day-to-day work to support the PUD’s financial portfolio and long-term business plan. If you would like to make a difference in your community and be proud of where you work, consider a career in public power at Klickitat PUD. We believe that each employee is vital in providing meaningful, high quality service to our customers and community. Customer satisfaction is inherent to the success of the Utility and is our number one priority. After all, the PUD is "owned by those it serves." As an Employer of Choice, we recognize the value and reward the contributions of our talented workforce. At Klickitat PUD, we offer a competitive wage, state retirement, and a comprehensive benefit package with all of our positions. We strive to recruit, retain and develop a dedicated, competent workforce to meet the needs of our Utility and the community we serve. About the PUD General The District is a municipal corporation of the State of Washington, formed by a vote of the electorate in 1938. The District exists under and by virtue of Title 54 RCW for the purpose of engaging in the purchase, generation, transmission, distribution and sale of electric energy and water and sewer service. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

John Ledyard Honored Jolm Ledyard Honored Articles on the Pacific

John Ledyard Honored 79 great studies of the Indians and worked with representatives of the Bureau of American Ethnology. He had been a farmer, post trader at the Lemhi Indian Agency, lawyer and County Attorney, State Senator, and teacher of history and science in the High School of Salmon, Idaho. Much regret is expressed that most of his Indian lore wa~ unrecorded and is lost unless others can glean some of it in the same fields he had tilled so faithfully. Jolm Ledyard Honored At the annual meeting of the New London County Historical ociety (Connecticut) a bronze tablet commemorating John Led yard was unveiled at the Shaw mansion. The occasion had added significance since it was the 150th anniversary of the great voy age of Captain James Cook to Hawaii and the Northwest Coast of America and John Ledyard was a valued member of that ex pedition. Ledyard was born at Groton, across the river from New London, Connecticut, in 1751 and died in Cairo, Egypt on January 17, 1789. He was the most distinguished American traveler of his day. At the time of the recent memorial a paper was prepared giving a sketch of his biography and an appreciation of his achievements. It was from the pen of a distinguished citi zen of New London, Howard Palmer, Fellow of the Royal Geo graphical Society and President of the American Alpine Club. That paper is well worth saving in the archives of the Pacific Northwest. It is not lmown whether separates are to be published but it appeared in full in The Evening Day, of New London, Connecticut, on Saturday, October 6, 1928, page 12. -

Matrices of 'Love and Theft': Joan Baez Imitates Bob Dylan

Twentieth-Century Music 18/2, 249–279 © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi: 10.1017/S1478572221000013 Matrices of ‘Love and Theft’: Joan Baez Imitates Bob Dylan MIMI HADDON Abstract This article uses Joan Baez’s impersonations of Bob Dylan from the mid-1960s to the beginning of the twenty-first century as performances where multiple fields of complementary discourse con- verge. The article is organized in three parts. The first part addresses the musical details of Baez’s acts of mimicry and their uncanny ability to summon Dylan’s predecessors. The second con- siders mimicry in the context of identity, specifically race and asymmetrical power relations in the history of American popular music. The third and final section analyses her imitations in the context of gender and reproductive labour, focusing on the way various media have shaped her persona and her relationship to Dylan. The article engages critical theoretical work informed by psychoanalysis, post-colonial theory, and Marxist feminism. Introduction: ‘Two grand, Johnny’ Women are forced to work for capital through the individuals they ‘love’. Women’s love is in the end the confirmation of both men’s and their own negation as individ- uals. Nowadays, the only possible way of reproducing oneself or others, as individuals and not as commodities, is to dam this stream of capitalist ‘love’–a ‘love’ which masks the macabre face of exploitation – and transform relationships between men and women, destroying men’s mediatory role as the representatives of state and capital in relation to women.1 I want to start this article with two different scenes from two separate Bob Dylan films. -

Ain't Goin' Nowhere — Bob Dylan 1967 Page 1

AIN 'T GOIN ' NOWHERE BOB DYLAN 1967 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES , RELEASES , TAPES & BOOKS . © 2001 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Ain't Goin' Nowhere — Bob Dylan 1967 page 1 CONTENTS: 1 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................... 2 2 THE YEAR AT A GLANCE ................................................................................................... 2 3 CALENDAR .............................................................................................................................. 2 4 RECORDINGS ......................................................................................................................... 3 5 JOHN WESLEY HARDING ................................................................................................... 3 6 SONGS 1967 .............................................................................................................................. 5 7 SOURCES .................................................................................................................................. 6 8 SUGGESTED READINGS ...................................................................................................... 7 8.1 GENERAL BACKGROUND ..................................................................................................... -

ONE HUNDRED YEARS of PEACE: Memory and Rhetoric on the United States/ Canadian Border, 1920-1933

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF PEACE: Memory and Rhetoric on the United States/ Canadian Border, 1920-1933 Paul Kuenker, Ph.D. Student, School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, Arizona State University In the fall of 2010, artists Annie Han and Daniel Mihalyo of the Seattle- based Lead Pencil Studio installed their newest sculpture adjacent to the border crossing station located at Blaine, Washington and Surrey, British Columbia on the U.S./Canadian border. Funded by the U.S. General Services Administration’s Art in Architecture program as part of its renovation of the border crossing station, Han and Mihalyo’s Non-Sign II consists of a large rectangular absence created by an intricate web of stainless steel rods (Figure 1). The sculpture evokes the many billboards that dot the highway near the border, yet this “permanent aperture between nations,” as Mihalyo refers to it, frames only empty space. According to Mihalyo, the sculpture plays on the idea of a billboard in order to “reinforce your attention back to the landscape and the atmosphere, the thing that the two nations share in common.”1 Though it may or may not have been their intention, the artists ofNon- Sign II placed the work in a location where it is easily juxtaposed with a border monument from a different era—a concrete archway situated on the boundary between the United States and Canada. Designed by prominent road-builder and Pacific Highway Association President Samuel Hill, the Peace Arch was formally dedicated at a grand ceremony held on September 6, 1921, to celebrate over one hundred years of peace between the United States, Great Britain and Canada since the 1814 Treaty of Ghent (Figure 2). -

African American Resource Guide

AFRICAN AMERICAN RESOURCE GUIDE Sources of Information Relating to African Americans in Austin and Travis County Austin History Center Austin Public Library Originally Archived by Karen Riles Austin History Center Neighborhood Liaison 2016-2018 Archived by: LaToya Devezin, C.A. African American Community Archivist 2018-2020 Archived by: kYmberly Keeton, M.L.S., C.A., 2018-2020 African American Community Archivist & Librarian Shukri Shukri Bana, Graduate Student Fellow Masters in Women and Gender Studies at UT Austin Ashley Charles, Undergraduate Student Fellow Black Studies Department, University of Texas at Austin The purpose of the Austin History Center is to provide customers with information about the history and current events of Austin and Travis County by collecting, organizing, and preserving research materials and assisting in their use. INTRODUCTION The collections of the Austin History Center contain valuable materials about Austin’s African American communities, although there is much that remains to be documented. The materials in this bibliography are arranged by collection unit of the Austin History Center. Within each collection unit, items are arranged in shelf-list order. This bibliography is one in a series of updates of the original 1979 bibliography. It reflects the addition of materials to the Austin History Center based on the recommendations and donations of many generous individuals and support groups. The Austin History Center card catalog supplements the online computer catalog by providing analytical entries to information in periodicals and other materials in addition to listing collection holdings by author, title, and subject. These entries, although indexing ended in the 1990s, lead to specific articles and other information in sources that would otherwise be time-consuming to find and could be easily overlooked. -

SAMUEL HILL: His Life, His Friends, and His Accomplishments

SAMUEL HILL: His life, his friends, and his accomplishments “We have found the Garden of Eden. It is the garden spot of the world — the most beautiful country I have ever seen. I took Mary up on top of the mountain and showed her the kingdom of the earth. Just think of a place where you can raise apples, peaches, quinces, corn, potatoes, watermelons, nineteen varieties of grapes, plums, apricots, strawberries, walnuts, almonds and everything except oranges . I am going to incorporate a company called ‘The Promised Land Company’.” (October 18, 1907, from a letter sent by Samuel Hill to his brother, Dr. Richard Junius Hill.) The Promised Land Company, later known as Maryhill, Washington, eventually failed due to irrigation difficulties and a world war. Left in this wake was a huge Grecian-doric castle museum, dedicated to international art; a replica of England’s Stonehenge, dedicated to peace; and a colorful history of our people: a queen, a Folies Bergere denseuse, a sugar heiress, and an empire builder. The story of the castle begins in 1913 and continues today. Samuel Hill executed plans for the building of a castle on a rocky promontory high above the second largest river in the United States. Mr. Hill, a strange mixture of cosmopolite and farmer, intended to use his castle as a residence for entertaining illustrious friends and royalty. He was anxious to show them the beauties of the West and to return, in a good manner, the hospitality that had been extended to him. For his good friend, King Albert, Samuel had the Belgian crest engraved above the doors. -

A Retired Muscoda Farmer Receives His Medal of Honor 40 Years Late

1 A Retired Muscoda Farmer C.S.S. Alabama, a commerce raider. The Rebel ship, under the command of receives his Medal of Honor 40 Captain Raphael Semmes, had had great years late success, sinking 65 union vessels (mostly merchant ships) since her commissioning on August 24, 1862. She had taken $6,000,000 in prizes (about $123,000,000 in today’s dollars). The ship now was badly in need of resupply and refitting. Crew of the Kearsarge shortly after the battle of Cherbourg In 1904 John Hayes was a 72 year old retired Navy sailor living on a pension, in Muscoda Wisconsin. It was a long A PAINTING OF THE C. S. S. ALABAMA way from Newfoundland where he was born. He had farmed from the late 1860’s For this purpose the Alabama put in to till his retirement in the Port Andrew the port of Cherbourg, France on June area, near the Wisconsin River. He had 14, 1864. This is where the Kearsarge, not always been a farmer though. In under the command of John A. Winslow his youth he had been a cooper. Tiring finally overtook her. of that trade he signed to go to sea on a British Merchant ship. In 1857, at the age of 24, he joined the U.S. Navy, and served on the Pacific Coast for two years. He then returned to the merchant service. When the Civil War began on 1861, John Hayes who loved his adopted country, determined to rejoin the U.S. Navy and serve in the way he knew best.