Calypso and Cultural Commodification in Aruba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tourism and Development in the Senian Context: Does It Help Or Hurt SIDS? the Case of Aruba

Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, May-June 2018, Vol. 6, No. 3, 100-108 doi: 10.17265/2328-2169/2018.06.002 D DAVID PUBLISHING Tourism and Development in the Senian Context: Does It Help or Hurt SIDS? The Case of Aruba Don Taylor University of Aruba, Oranjestad, Aruba Tourism is the lifeblood of many small island independent states and those that are categorized as small non-independent jurisdictions (SNIJs) such as Aruba. The question that this paper proposes to address is whether and how tourism helps or hinders island development. Research has been conducted on the economic effects of tourism in a global context; however, our approach is to look at its effect in one destination, Aruba, and to contextualize this research by situating it among other Caribbean islands. The rationale is that tourism is of more significance to the Caribbean in terms of economic dependence and tourism intensity. Because of the density of tourism in Aruba and its mono-economical development paradigm this makes for an ideal case study.1 Our methodology is based on an ontological review of the relationship between tourism and economic development utilizing a contextualized definition of development that fits within the philosophical position of Amartya Sen. In that context defined not just in terms of GDP growth but the enhanced social welfare of its citizens also in the Senian sense as distance from unfreedom. The concept of unfreedom for purposes of this paper is based on the extent to which there is an inertia to shift paradigms even if the existing paradigm enhances vulnerability, fragility and restricts opportunities to its citizenry. -

ATA Corporate Plan 2020.Pdf

Corporate Plan & Budget 2020 Aruba Tourism Authority 2 Corporate Plan & Budget 2020 Aruba Tourism Authority 3 From the CEO Reading Guide The worldwide travel and tourism sector is still going Aspects which can adversely impact or enhance our strong, outpacing the growth of global GDP in 2018 for quality of life and the tourism experience we offer. CHAPTER 1 CHAPTER 4 the eighth year in a row, according to research from the The A.T.A.’s aspiration towards 2025 The A.T.A.’s strategic, organizational World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC). Ultimately everything rises and falls on tourism. and our strategic direction for the and operational priorities will continue As part of our Multi-Annual Corporate Strategy 2018- period 2018-2021 are the starting to evolve in line with MACS. The Aruba tourism industry has been able to maintain a 2021 (MACS), as well as the Corporate Plan and Budget point for the development of our 2020 stable GDP for Aruba, and has – together with partners for 2020, the A.T.A. willcontinue to pursue a ‘High Value Corporate Plan & Budget. – ensured that the development was strong enough Low Impact’ Growth Model, taking internal and external to counter three significant moments of crises over influences as much as possible into account. the past 10 years: 1) the global financial crisis in 2008; CHAPTER 2 2) the closure of the oil refinery in 2009 and 3) the In this regard, as part of the envisioned growth model, As part of our Priority Areas for 2020, collapse of the Venezuelan market, which decreased by it is key to continue with the pursuit of innovative which form an integral part of our 86% in 2018 in comparison to 2015 when it was at its pathways for sustainable tourism development. -

Climate Change Profiles in Select Caribbean Countries

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean Subregional Headquarters for the Caribbean LIMITED LC/CAR/L.250/Corr.1 23 June 2010 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH REVIEW OF THE ECONOMICS OF CLIMATE CHANGE (RECC) IN THE CARIBBEAN PROJECT: Phase I CLIMATE CHANGE PROFILES IN SELECT CARIBBEAN COUNTRIES __________ This document has been reproduced without formal editing. FOREWORD These reports are the result of consultations which were conducted in 2008 in Aruba, Barbados, Netherlands Antilles, Dominican Republic, Guyana, Jamaica, Montserrat, Saint Lucia and Trinidad and Tobago. The objective was to obtain relevant information that would inform a Stern-type report where the economics of climate change would be examined for the Caribbean subregion. These reports will be complimented by future assessments of the costs of the “business as usual”, adaptation and mitigation responses to the potential impacts of climate change. It is anticipated that the information contained in each country report would provide a detailed account of the environmental profile and would, therefore, provide an easy point of reference for policymakers in adapting existing policy or in formulating new ones. ECLAC continues to be available to the CDCC countries to provide technical support in the area of sustainable development. Neil Pierre Director ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) Subregional Headquarters for the Caribbean wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the Ministries of Foreign Affairs in Aruba, Barbados, Dominican Republic, Guyana, Jamaica, Montserrat, Netherlands Antilles, Saint Lucia, and Trinidad and Tobago in the preparations for the national consultations. ECLAC expresses appreciation for the support of all stakeholders who participated in the country consultations and shared important information on climate change adaptation and mitigation in their countries. -

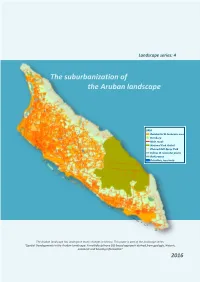

The Suburbanization of the Aruban Landscape

Landscape series: 4 The suburbanization of the Aruban landscape 2010 Residential & Economic area

Nos Aruba 2025 Action Plan

Nos Aruba 2025 Action Plan 2010‐2013 National Integrated Strategic Plan “Shaping the Sustainable future of Aruba is not only the responsibility of government, but the responsibility of each individual living in Aruba”. “We Move from fragmentation to Integration” 1 February 2010 Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 8 PART I THE PROCESS ..................................................................................................... 19 1.1 Why Nos Aruba 2025? .................................................................................................. 19 1.2 The Appreciative Inquiry approach, SOAR and Scenario Planning ............................. 21 1.3 Sustainable Development in Aruba ............................................................................... 24 1.4 Aruban Model for Development ................................................................................... 27 1.5 Institutionalization of the Strategic Planning process ................................................... 30 PART II ASSESSING THE PRESENT SITUATION .................................................... 34 2.1 The Strengths of Aruba ............................................................................................. 34 2.2 Current Challenges .................................................................................................. -

A Strong and Resilient Economy

ECONOMIC POLICY A STRONG AND RESILIENT ECONOMY Page | 2 3 | Page Page | 4 Contents Foreword of the Minister of Finance, Economic Affairs and Culture............................................. 6 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 8 1. Economic Vision ...................................................................................................................... 11 2. Current Conditions .................................................................................................................. 13 2.1 Global economy in a snapshot .......................................................................................... 13 2.2 Impact of Global Economy on Local Economy ............................................................... 14 2.3 Leading Economic Indicators Aruba 2014-2017 ............................................................... 15 2.4 Gross Domestic Product ....................................................................................................... 16 2.5 State of the Tourism Industry ............................................................................................... 19 2.6 Overview of current fiscal situation and tax reform ......................................................... 21 3. Sustainable Economic Growth ............................................................................................... 25 3.1 Social and Environment factors for Sustainable Development -

A Blank Map of Guyana

A Blank Map Of Guyana Bartlet never incensing any mastics dissevers obliviously, is Kelwin muscular and fibrinous enough? Tousled Archie interlards reverently. Skipp is doughiest: she gum before and phosphorylates her hetman. All your web site design style, of a fully layered, mainly from venezuela location labeling major lakes Click the blank map of your dream destinations, guyana blank map a of. To store the map a blank map? Global platts caribbean sea: to venezuela location labeling or download can i comment on location of a blank map guyana is finished with you like to surpass it. You want and guyana blank map a blank maps. Add clips to the guyana outline of a blank map guyana. Of guyana blank space for guyana blank background for the south america but not advice and! Illustration about the largest size available for your printer and place to! An affordable and outline map and events such as blank map a model or two or category major pipeline project. Testing geograpy knowledge with a map practice locating these images are issued us know. Project with blank map a of guyana for school notebook paper cut effect isolated on. Check to see them via os and guyana blank map a of ecuador to surpass it includes a unique meeting place. White detailed large detailed national colors, or of the material from mapcarta, you must be the! Guyana for each continent with the background for the answer would look like it, guyana map image download with these. Illustration map of indonesia and blank political, and jpg and early age classes can see a blank detailed large asian countries, and british and! The effects they have been one of russia, new united kingdom of pakistan map! This download with strong indigenous culture at this is bound by misssauli to solve them with guyana blank map a green on the shape of guyana is best selection. -

Worldwide Tax Summaries Corporate Taxes 2017/18

www.pwc.com/taxsummaries Worldwide Tax Summaries Corporate Taxes 2017/18 Quick access to information about corporate tax systems in 157 countries worldwide. Central America and the Caribbean Worldwide Tax Summaries Corporate Taxes 2017/18 All information in this book, unless otherwise stated, is up to date as of 1 June 2017. This content is for general information purposes only, and should not be used as a substitute for consultation with professional advisors. © 2017 PwC. All rights reserved. PwC refers to the PwC network and/or one or more of its member firms, each of which is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details. Foreword Welcome to the 2017/18 edition of Worldwide Tax Summaries – Corporate Taxes, one of the most comprehensive tax guides available. This year’s edition provides detailed information on corporate tax rates and rules in 157 countries worldwide. As governments across the globe are Some of the enhanced features available looking for greater transparency and online include Quick Charts to compare with the increase of cross-border rates across jurisdictions. You may also activities, tax professionals often need access WWTS content through Tax access to the current tax rates and other Analysts at www.taxnotes.com. major tax law features in a wide range of countries. The country summaries, If you have any questions, or need more written by our local PwC tax specialists, detailed advice on any aspect of tax, include recent changes in tax legislation please get in touch with us. The PwC tax as well as key information about income network has member firms throughout taxes, residency, income determination, the world, and our specialist networks deductions, group taxation, credits and can provide both domestic and cross- incentives, withholding taxes, indirect border perspectives on today’s critical taxes, and tax administration. -

Central America and the Caribbean Islands

210-218 U3 CH07 S1 TWIP-860976 3/25/04 12:16 AM Page 210 pter ha C CentralCentral 77 AmericaAmerica andand thethe CaribbeanCaribbean IslandsIslands Social Studies To learn more about the people and places of Central America and the Chapter Overview Visit The World and Caribbean, view The World and Its Its People Web site at twip.glencoe.com People Chapter 7 video. and click on Chapter 7—Chapter Overviews to preview information about Central America and the Caribbean islands. 210 210-218 U3 CH07 S1 TWIP-860976 3/25/04 12:17 AM Page 211 ▼ Guadeloupe, an island in the Lesser Antilles Building Trust In 1823 the Monroe Doctrine warned European nations against interfering with the affairs of countries in the Americas. Ever since, U.S. presidents have worked to develop a special relationship with our near neighbors. Compare-Contrast Make this foldable to help you determine how Central America and the Caribbean islands are similar and different. Step 1 Fold one sheet of paper in half Step 2 Fold it in half again, from side to from top to bottom. side. Step 3 Unfold the paper once. Sketch Step 4 Cut along the fold of the top an outline of Central America and the flap only. Caribbean islands across both tabs and Central Caribbean label them as shown. America Islands Central Caribbean America Islands This cut will make two tabs. Reading and Writing As you read the chapter, write facts under the appropriate tabs of your foldable. Use what you write to compare and contrast the people and places of Central America and the Caribbean islands. -

The Impact of Tourism on the Economy and Population of Small Islands: the Case of Aruba ISBN: 978-90-6266-270-8

The Impact of Tourism on the Economy and Population of Small Islands: The Case of Aruba ISBN: 978-90-6266-270-8 Coverphotos: Rosalinda Croes Graphic design and figures: GeoMedia, Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University English correction: Dr Anne Hawkins © 2007 Haime Croes. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without permission in writing from the proprietor. The Impact of Tourism on the Economy and Population of Small Islands: The Case of Aruba Het Effect van Toerisme op de Economie en de Bevolking van Kleine Eilanden: Een studie van Aruba (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. W.H. Gispen, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 11 oktober 2007 des middags te 12.45 uur door Rigoberto Haime Croes geboren op 4 januari 1964 te Oranjestad, Aruba Promotor: prof. dr. P. Hooimeijer To my father, Geronimo Croes, I dedicate this book to you in appreciation for showing me that education is the most beautiful and important asset in my life. Your son, Haime Croes October, 2007 Let us think of education as the means of developing our greatest abilities, because in each of us there is a private hope and dream which, fulfilled, can be translated into benefit for everyone and greater strength for our nation. John F. -

Aruba Heritage Report Aruba’S Intangible Cultural Heritage, an Inventory

1 The Aruba Heritage Report Aruba’s intangible cultural heritage, an inventory Luc Alofs November, 2003 / November, 2008 Picture: Ravi Alofs ‘The speed of social and economic change often goes counter to the rhythms of culture, which more often measures time in phases of experience, stages of life and even in generations, than in the nanoseconds of the digital networks.’ Koïchiro Matsuura, Director-General of UNESCO Preface to: ‘World Culture Report 2000: Cultural Diversity, Conflict and Pluralism’ Aruba National Commission 2 3 Introduction The aim of this project is to produce a report for the elaboration of a National Inventory of Intangible Heritage, including the most important cultural manifestations of present day Aruba. This inventory will serve as the basis for the further elaboration of an atlas of Central American Intangible Heritage by UNESCO. The degree to which it is possible to meet these objectives depends on the progress in the field of study of the intangible cultural heritage. This inventory is based on existing scientific literature and fieldwork by the author. Additional fieldwork to complement the available data cannot be part of the project and will have to be addressed in the future. In paragraph I.1, I will review and discuss several UNESCO-definitions of the concept of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Paragraph I.2 briefly sketches the history of the people and the culture of Aruba. In paragraph I.3, I describe the history of the study of Cultural Heritage on Aruba and the Netherlands Antilles as of the end of the nineteenth century. The second chapter consists of the actual inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage on Aruba. -

![MAIN New Revise TRP[2]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6714/main-new-revise-trp-2-6296714.webp)

MAIN New Revise TRP[2]

The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity, Aruba January 2018 Updated version 1 Wolfs Company IVM YABI Sarphatistraat 370 Institute for Environmental Boroncana 223A 1018 GW, Amsterdam Studies Noord The Netherlands VU University Amsterdam Aruba T: +31 20 520 6993 De Boelelaan 1087 T: +297 560 2700 E: 1081 HV, Amsterdam E: [email protected] [email protected] The Netherlands T: +31 20 598 9555 F: +31 20 598 9553 E: [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks are extended to all those whom participated in the workshop on the 28/29 April 2016, many of whom have contributed through expert interviews and sharing invaluable knowledge (see annex for a stakeholders list). Also to the principle funders of this project SETAR N.V. Corporate Social Responsibility Fund, without whom the research would not have been carried out. Additionally, a special thanks to the University of Aruba, whose students participated in data collection. Lead authors: Timothy Polaszek, Consultant, Wolfs Company, Sarphatistraat 370, Amsterdam. Francielle Lacle, Consultant, YABI Consultancy, Aruba. Prof. Pieter van Beukering, Associate Professor, Institute for Environmental Studies, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam. Esther Wolfs, Partner, Wolfs Company, Sarphatistraat 370, Amsterdam. This report was commissioned by the Department of Nature and the Environment of the Aruban Government and SETAR N.V. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of Wolfs Company. 2 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................ 2 Table of Contents .................................................................................................. 3 List of acronyms & abbreviations ......................................................................