Aruba, Kingdom of the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Good Governance' in the Dutch Caribbean

Obstacles to ‘Good Governance’ in the Dutch Caribbean Colonial- and Postcolonial Development in Aruba and Sint Maarten Arxen A. Alders Master Thesis 2015 [email protected] Politics and Society in Historical Perspective Department of History Utrecht University University Supervisor: Dr. Auke Rijpma Internship (BZK/KR) Supervisor: Nol Hendriks Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 2 1. Background ............................................................................................................................ 9 1.1 From Colony to Autonomy ......................................................................................................... 9 1.2 Status Quaestionis .................................................................................................................... 11 Colonial history .............................................................................................................................. 12 Smallness ....................................................................................................................................... 16 2. Adapting Concepts to Context ................................................................................................. 19 2.1 Good Governance ..................................................................................................................... 19 Development in a Small Island Context ........................................................................................ -

The People of Aruba, Continuity and Change Census 2000 Special Reports February 2002

FOURTH POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS, ARUBA The People of Aruba, Continuity and Change Census 2000 Special Reports February 2002 CENTRAL BUREAU OF STATISTICS - ARUBA Census Statistics for progress 2000 FOURTH POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS ARUBA OCTOBER 14, 2000 The People of Aruba Continuity and Change CENTRAL BUREAU OF STATISTICS Oranjestad, February 2002 Where to order Central Bureau of Statistics L.G. Smith Boulevard 160, Oranjestad, Aruba, Dutch Caribbean Phone: (297) 5837433 Fax: (297) 5838057 Preface From 14 October till 22 October 2000 the Fourth Population and Housing Census was conducted on Aruba. After a week of intensive work in which a group of 1256 enumerators visited all households on the island, the census team started with the data-processing, editing and tabulation of the census results. To speed up this process the Central Bureau of Statistics made use of some innovative techniques such as imaging and computer aided coding. Already in June 2001 the CBS was able to finish a CD-ROM with Selected Tables. Up to now results from the population census have been used by a large group of organizations from within and outside the public sector. A population census is an ideal opportunity to draw a picture of the social and demographic characteristics of a population. In this publication the CBS highlights some interesting changes that have taken place on Aruba during the last ten years. The rapid economic developments during the last decade of the previous century have triggered an enormous growth of the population. In less than ten years time the population increased from 66,687 in 1991 to 90,506 in 2000. -

Law and Emotions Within the Kingdom of the Netherlands Nanneke Quik-Schuijt

University of Baltimore Journal of International Law Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 3 Volume IV, No. 1 2015-2016 2016 A Case Study: Law and Emotions Within the Kingdom of the Netherlands Nanneke Quik-Schuijt Irene Broekhuijse Open University of the Netherlands, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ubjil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Quik-Schuijt, Nanneke and Broekhuijse, Irene (2016) "A Case Study: Law and Emotions Within the Kingdom of the Netherlands," University of Baltimore Journal of International Law: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ubjil/vol4/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 LAW AND EMOTIONS.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 3/21/16 6:37 PM\ A Case Study: Law and Emotions Within the Kingdom of the Netherlands Nanneke Quik-Schuijt & Irene Broekhuijse AUTHORS: Nanneke Quik-Schuijt, LLM; Member of the Senate of the Netherlands from June 12th 2007, until June 9th 2015. Before that she served as a judge (dealing with cases involving children), from 1975-1990. Then she became the vice-president of the district court of Utrecht (1990-2007). She was i.a. involved with Kingdom Affairs. Irene Broekhuijse LLM, PhD; Assistant Professor Constitutional and Administrative Law at the Open University of the Netherlands. -

Closer Ties: the Dutch Caribbean and the Aftermath of Empire, 1942-2012

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Closer Ties: The Dutch Caribbean and the Aftermath of Empire, 1942-2012 Chelsea Schields The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1993 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] CLOSER TIES: THE DUTCH CARIBBEAN AND THE AFTERMATH OF EMPIRE, 1942-2012 by CHELSEA SCHIELDS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 CHELSEA SCHIELDS All Rights Reserved ii Closer Ties: The Dutch Caribbean and the Aftermath of Empire, 1942-2012 by Chelsea Schields This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Professor Dagmar Herzog ______________________ _________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Professor Helena Rosenblatt ______________________ _________________________________________ Date Executive Officer Professor Mary Roldán Professor Joan Scott Professor Todd Shepard Professor Gary Wilder Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract Closer Ties: The Dutch Caribbean and the Aftermath of Empire, 1942-2012 by Chelsea Schields Advisor: Professor Dagmar Herzog This dissertation examines the unique trajectory of decolonization in the Netherlands and its former Caribbean colonies and argues that sexual and reproductive politics have played a pivotal role in forging a postcolonial commonwealth state. -

Aruba Country Profile Health in the Americas 2007

Aruba Netherlands Antilles Colombia ARUBA Venezuela 02010 Miles Aruba Netherlands Oranjestad^ Antilles Curaçao Venezuela he island of Aruba is located at 12°30' North and 70° West and lies about 32 km from the northern coast of Venezuela. It is the smallest and most western island of a group of three Dutch Leeward Islands, the “ABC islands” of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao. T 2 Aruba is 31 km long and 8 km wide and encompasses an area of 180 km . GENERAL CONTEXT AND HEALTH traction of 2.4% is projected (Table 1). While Aruba has made DETERMINANTS considerable progress toward alleviating poverty, available data suggest that income inequality is still considerably larger than in Aruba’s capital is Oranjestad,and the island divides geograph- countries with comparable income levels. ically into eight districts: Noord/Tanki Leendert,Oranjestad-West, According to the Centrale Bank van Aruba, at the end of 2005, Oranjestad-East, Paradera, Santa Cruz, Savaneta, San Nicolas- inflation stood at 3.8%, compared to 2.8% a year earlier. Mea- North, and San Nicolas-South. The average temperature is 28°C sured as a 12-month average percentage change,the inflation rate with a cooling northeast tradewind. Rainfall averages about accelerated by nearly 1% to 3.4% in 2005, reflecting mainly price 500 mm a year, with October, November, December, and January increases for water, electricity, and gasoline following the rise in accounting for most of it. Aruba lies outside the hurricane belt oil prices on the international market. At the end of 2005, the and at most experiences only fringe effects of nearby heavy trop- overall economy continued to show an upward growth trend ical storms. -

Initial Report of the Kingdom of the Netherlands

INITIAL REPORT OF THE KINGDOM OF THE NETHERLANDS SUBMITTED UNDER ARTICLE 8, PARAGRAPH 1 OF THE OPTIONAL PROTOCOL TO THE CONVENTION ON THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD ON THE INVOLVEMENT OF CHILDREN IN ARMED CONFLICT Introduction The Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict (New York, 25 May 2000) was approved for the entire Kingdom of the Netherlands by the Kingdom Act of 18 December 20081 and entered into force for the entire Kingdom on 24 October 2009. The Dutch translation of the Protocol was published in the Dutch Treaty Series 2001, 131. At the time of the ratification the Kingdom of the Netherlands consisted of the Netherlands, the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba. In 2010, the Kingdom of the Netherlands has undergone a process of constitutional reform, which has now reached fruition. The changes concern the Netherlands Antilles, a country that until recently was made up of the islands of Curaçao, Sint Maarten, Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba. The reforms are based on the results of referenda and on decisions taken by representative assemblies about the islands’ future status. The amended Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands entered into force on 10 October 2010, on which date the Netherlands Antilles ceased to exist. In the new constitutional structure, Curaçao and Sint Maarten have acquired the status of countries within the Kingdom (like the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba before the changes). Aruba retains the separate country status it has had since 1986. Thus, from 10 October 2010 the Kingdom consists of four, rather than three, equal countries: the Netherlands, Aruba, Curaçao and Sint Maarten. -

Tourism and Development in the Senian Context: Does It Help Or Hurt SIDS? the Case of Aruba

Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, May-June 2018, Vol. 6, No. 3, 100-108 doi: 10.17265/2328-2169/2018.06.002 D DAVID PUBLISHING Tourism and Development in the Senian Context: Does It Help or Hurt SIDS? The Case of Aruba Don Taylor University of Aruba, Oranjestad, Aruba Tourism is the lifeblood of many small island independent states and those that are categorized as small non-independent jurisdictions (SNIJs) such as Aruba. The question that this paper proposes to address is whether and how tourism helps or hinders island development. Research has been conducted on the economic effects of tourism in a global context; however, our approach is to look at its effect in one destination, Aruba, and to contextualize this research by situating it among other Caribbean islands. The rationale is that tourism is of more significance to the Caribbean in terms of economic dependence and tourism intensity. Because of the density of tourism in Aruba and its mono-economical development paradigm this makes for an ideal case study.1 Our methodology is based on an ontological review of the relationship between tourism and economic development utilizing a contextualized definition of development that fits within the philosophical position of Amartya Sen. In that context defined not just in terms of GDP growth but the enhanced social welfare of its citizens also in the Senian sense as distance from unfreedom. The concept of unfreedom for purposes of this paper is based on the extent to which there is an inertia to shift paradigms even if the existing paradigm enhances vulnerability, fragility and restricts opportunities to its citizenry. -

ATA Corporate Plan 2020.Pdf

Corporate Plan & Budget 2020 Aruba Tourism Authority 2 Corporate Plan & Budget 2020 Aruba Tourism Authority 3 From the CEO Reading Guide The worldwide travel and tourism sector is still going Aspects which can adversely impact or enhance our strong, outpacing the growth of global GDP in 2018 for quality of life and the tourism experience we offer. CHAPTER 1 CHAPTER 4 the eighth year in a row, according to research from the The A.T.A.’s aspiration towards 2025 The A.T.A.’s strategic, organizational World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC). Ultimately everything rises and falls on tourism. and our strategic direction for the and operational priorities will continue As part of our Multi-Annual Corporate Strategy 2018- period 2018-2021 are the starting to evolve in line with MACS. The Aruba tourism industry has been able to maintain a 2021 (MACS), as well as the Corporate Plan and Budget point for the development of our 2020 stable GDP for Aruba, and has – together with partners for 2020, the A.T.A. willcontinue to pursue a ‘High Value Corporate Plan & Budget. – ensured that the development was strong enough Low Impact’ Growth Model, taking internal and external to counter three significant moments of crises over influences as much as possible into account. the past 10 years: 1) the global financial crisis in 2008; CHAPTER 2 2) the closure of the oil refinery in 2009 and 3) the In this regard, as part of the envisioned growth model, As part of our Priority Areas for 2020, collapse of the Venezuelan market, which decreased by it is key to continue with the pursuit of innovative which form an integral part of our 86% in 2018 in comparison to 2015 when it was at its pathways for sustainable tourism development. -

Joyce Pereira Valorization of Papiamento

Valorization of Papiamento in Aruban society and education, in historical, contemporary and future perspectives 1 2 Valorization of Papiamento in Aruban society and education, in historical, contemporary and future perspectives Proefschrift 3 ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de University of Curaçao dr. Moises da Costa Gomez op gezag van de rector magnificus dr. F.B.G. de Lanoy, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de aula van de universiteit op 15 november 2018 om 16.00 uur precies door Joyce Lomena Pereira geboren op 27 januari 1946 te Willemstad, Curaçao Promotiecommissie Voorzitter: Dr. Francis de Lanoy Rector Magnificus Promotoren: Prof. dr. Ronald Severing University of Curaçao Prof. dr. Ludo Verhoeven University of Curaçao; Radboud University Nijmegen Prof. dr. Nicholas Faraclas University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Leden van de manuscriptcommissie: Prof. dr. Wim Rutgers University of Curaçao Prof. dr. Eliane Segers Radboud University Nijmegen; University of Twente Dr. Elisabeth Echteld Decaan Algemene Faculteit University of Curaçao Overige commissieleden: Prof. dr. Lodewijk Rogier University of Curaçao Prof. dr. Flora Goudappel University of Curaçao; Erasmus University Dr. Rose Mary Allen, University of Curaçao Faculty of Arts; Algemene Faculteit 4 © 2018 Joyce Pereira, Valorization of Papiamento in Aruban society and education, in historical, contemporary and future perspectives ISBN: 978-99904-69-41-7 Cover design: Smile Art & Design Illustration on cover: The Kibrahacha tree, (in Papiamento literally “breaking axes”), the Yel- low Poui or Tabebuia billbergii, Armando Goedgedrag This research was made possible by support from the General Faculty of the University of Curacao Dr. Moises da Costa Gomez, the University of Aruba, the Radboud University and the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras. -

Kingdom of the Netherlands Constitutional Law of the EU

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The Kingdom of the Netherlands Besselink, L.F.M. Publication date 2014 Document Version Submitted manuscript Published in Constitutional law of the EU member states Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Besselink, L. F. M. (2014). The Kingdom of the Netherlands. In L. Besselink, P. Bovend’Eert, H. Broeksteeg, R. de Lange, & W. Voermans (Eds.), Constitutional law of the EU member states (pp. 1187-1241). Kluwer. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 The Kingdom of the Netherlands Leonard F.M. Besselink1 1. This chapter is based in part on this author’s Grundstrukturen staatlichen Verfassungsrechts: Niederlande, in: Handbuch Ius Publicum Europaeum, Band I: Nationales Verfassungsrecht, Armin von Bogdandy, Pedro Cruz Villalón, Peter M. -

Climate Change Profiles in Select Caribbean Countries

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean Subregional Headquarters for the Caribbean LIMITED LC/CAR/L.250/Corr.1 23 June 2010 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH REVIEW OF THE ECONOMICS OF CLIMATE CHANGE (RECC) IN THE CARIBBEAN PROJECT: Phase I CLIMATE CHANGE PROFILES IN SELECT CARIBBEAN COUNTRIES __________ This document has been reproduced without formal editing. FOREWORD These reports are the result of consultations which were conducted in 2008 in Aruba, Barbados, Netherlands Antilles, Dominican Republic, Guyana, Jamaica, Montserrat, Saint Lucia and Trinidad and Tobago. The objective was to obtain relevant information that would inform a Stern-type report where the economics of climate change would be examined for the Caribbean subregion. These reports will be complimented by future assessments of the costs of the “business as usual”, adaptation and mitigation responses to the potential impacts of climate change. It is anticipated that the information contained in each country report would provide a detailed account of the environmental profile and would, therefore, provide an easy point of reference for policymakers in adapting existing policy or in formulating new ones. ECLAC continues to be available to the CDCC countries to provide technical support in the area of sustainable development. Neil Pierre Director ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) Subregional Headquarters for the Caribbean wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the Ministries of Foreign Affairs in Aruba, Barbados, Dominican Republic, Guyana, Jamaica, Montserrat, Netherlands Antilles, Saint Lucia, and Trinidad and Tobago in the preparations for the national consultations. ECLAC expresses appreciation for the support of all stakeholders who participated in the country consultations and shared important information on climate change adaptation and mitigation in their countries. -

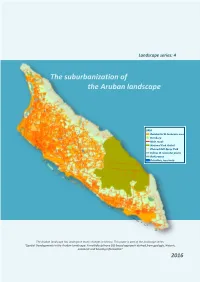

The Suburbanization of the Aruban Landscape

Landscape series: 4 The suburbanization of the Aruban landscape 2010 Residential & Economic area ![ Hooiberg Main roads National Park Arikok Planned Salt Spray Park Salinas & rainwater plains Golfcourses Retention_reservoirs The Aruban landscape has undergone many changes in history. This paper is part of the landscape series: “Spatial Developments in the Aruban Landscape: A multidisciplinary GIS-based approach derived from geologic, historic, economic and housing information” 2016 1 “We must spare no effort to free all of humanity, and above all our children and grandchildren, from the threat of living on a planet irredeemably spoilt by human activities, and whose resources would no longer be sufficient for their needs”. —United Nations Millennium Declaration (2000) — Contents The historical perspective 3 Population growth 4 Recent GDP 6 Suburban sprawl and rising housing costs 6 Information derived from historic maps 8 The landscape in early 20th century 8 Infrastructure 8 Mining 8 Agriculture 8 Windmills 8 Plantations 8 Saltpans 9 The relation between geological substrate and early land-use in 1911 9 The extent of Aloe cultivation in 1911 9 The extent of agriculture in 1911 10 Housing in 1911 and 2010 11 Infomation from Housing Censuses 12 Impact from the shift in housing on the landscape 15 Infrastructure in 2010 and in 1911 15 A layout for traffic congestion 15 Final remarks 18 Works Cited 19 Author: Ruud R. W. M. Derix, PhD Head department Spatial and Environmental Statistics Central Bureau of Statistics Aruba 2016 We like to thank our colleagues at the CBS for their comments on the manuscript. Special thanks to Marlon Faarup, Director CBS, for the thorough review and remarks on the final manuscript.