Manual De Prácticas Del Laboratorio De Paleontología

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sedimentology, Taphonomy, and Palaeoecology of a Laminated

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 243 (2007) 92–117 www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Sedimentology, taphonomy, and palaeoecology of a laminated plattenkalk from the Kimmeridgian of the northern Franconian Alb (southern Germany) ⁎ Franz Theodor Fürsich a, , Winfried Werner b, Simon Schneider b, Matthias Mäuser c a Institut für Paläontologie, Universität Würzburg, Pleicherwall 1, 97070 Würzburg, Germany LMU b Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und Geologie and GeoBio-Center , Richard-Wagner-Str. 10, D-80333 München, Germany c Naturkunde-Museum Bamberg, Fleischstr. 2, D-96047 Bamberg, Germany Received 8 February 2006; received in revised form 3 July 2006; accepted 7 July 2006 Abstract At Wattendorf in the northern Franconian Alb, southern Germany, centimetre- to decimetre-thick packages of finely laminated limestones (plattenkalk) occur intercalated between well bedded graded grainstones and rudstones that blanket a relief produced by now dolomitized microbialite-sponge reefs. These beds reach their greatest thickness in depressions between topographic highs and thin towards, and finally disappear on, the crests. The early Late Kimmeridgian graded packstone–bindstone alternations represent the earliest plattenkalk occurrence in southern Germany. The undisturbed lamination of the sediment strongly points to oxygen-free conditions on the seafloor and within the sediment, inimical to higher forms of life. The plattenkalk contains a diverse biota of benthic and nektonic organisms. Excavation of a 13 cm thick plattenkalk unit across an area of 80 m2 produced 3500 fossils, which, with the exception of the bivalve Aulacomyella, exhibit a random stratigraphic distribution. Two-thirds of the individuals had a benthic mode of life attached to hard substrate. This seems to contradict the evidence of oxygen-free conditions on the sea floor, such as undisturbed lamination, presence of articulated skeletons, and preservation of soft parts. -

Functional Anatomy and Mode of Life of the Latest Jurassic Crinoid Saccocoma

Functional anatomy and mode of life of the latest Jurassic crinoid Saccocoma MICHAŁ BRODACKI Brodacki, M. 2006. Functional anatomy and mode of life of the latest Jurassic crinoid Saccocoma. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 51 (2): 261–270. Loose elements of the roveacrinid Saccocoma from the Tithonian red Rogoża Coquina, Rogoźnik, Pieniny Klippen Belt, Poland, are used to test the contradictory opinions on the mode of life of Saccocoma. The investigated elements belong to three morphological groups, which represent at least two separate species: S. tenella, S. vernioryi, and a third form, whose brachials resemble those of S. vernioryi but are equipped with wings of different shape. The geometry of brachials’ articu− lar surfaces reveals that the arms of Saccocoma were relatively inflexible in their proximal part and left the cup at an angle of no more than 45°, then spread gradually to the sides. There is no evidence that the wings were permanently oriented in either horizontal or vertical position, as proposed by two different benthic life−style hypotheses. The first secundibrachial was probably more similar to the first primibrachial than to the third secundibrachial, in contrast to the traditional assump− tion. The winged parts of the arms were too close to the cup and presumably too stiff to propel the animal in the water effi− ciently. Swimming was probably achieved by movements of the distal, finely branched parts of the arms. The non− horizontal attitude of the winged parts of the arms is also not entirely consistent with the assumption that they functioned as a parachute. Moreover, the wings added some weight and thus increased the energy costs associated with swimming. -

Life and Death of Saccocoma Tenella (GOLDFUSS)

Swiss J Geosci (2011) 104 (Suppl 1):S99–S106 DOI 10.1007/s00015-011-0059-z Life and death of Saccocoma tenella (GOLDFUSS) Hans Hess • Walter Etter Received: 15 September 2009 / Accepted: 25 June 2010 / Published online: 19 April 2011 Ó Swiss Geological Society 2011 Abstract The morphology of the small stalkless Sacco- Das Skelett ist a¨ußerst leicht gebaut; die proximalen coma tenella is unique among crinoids. It is characterized Armglieder tragen seitlich abstehende ‘‘Schwimmplatten’’ by an extremely light skeleton with dish-like lateral wings oder Flu¨gel, die distalen gepaarte vertikale Fortsa¨tze wel- on the proximal brachials and peculiar paired vertical che die Nahrungsfurche flankieren. Die Arme sind reich processes flanking the food grooves of more distal verzweigt. Die Flu¨gel dienten offensichtlich zur vertikalen brachials. The arms are heavily branched. The lateral wings Bewegung. Die vertikalen Fortsa¨tze wurden als Fu¨hrung obviously were involved in vertical movement. For the fu¨r das Einrollen der Arme zu einem ‘‘Schnapp-Schwim- vertical processes a ‘‘baffle rail’’ function for arm curling men’’ gedeutet. Dabei wa¨ren sie durch Muskeln verbunden and ‘‘snap swimming’’ has been postulated, with muscles gewesen. Da Indizien fu¨r Muskeln zwischen den vertikalen between the processes. However, there is no evidence that Fortsa¨tzen fehlen, wird zur Nahrungsaufnahme das Modell the processes were connected by muscles. For food col- eines in der Wassersa¨ule ‘‘pulsierenden Trichters’’ vor- lection a ‘‘pulsating funnel’’ model in the water column is geschlagen, mit Fang von Plankton zwischen den Fortsa¨tzen advocated, with the processes serving to collect plankton wa¨hrend der Aufwa¨rtsbewegung der Arme. -

THE ECHINODERM NEWSLETTER Number 22. 1997 Editor: Cynthia Ahearn Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History Room

•...~ ..~ THE ECHINODERM NEWSLETTER Number 22. 1997 Editor: Cynthia Ahearn Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History Room W-31S, Mail Stop 163 Washington D.C. 20560, U.S.A. NEW E-MAIL: [email protected] Distributed by: David Pawson Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History Room W-321, Mail Stop 163 Washington D.C. 20560, U.S.A. The newsletter contains information concerning meetings and conferences, publications of interest to echinoderm biologists, titles of theses on echinoderms, and research interests, and addresses of echinoderm biologists. Individuals who desire to receive the newsletter should send their name, address and research interests to the editor. The newsletter is not intended to be a part of the scientific literature and should not be cited, abstracted, or reprinted as a published document. A. Agassiz, 1872-73 ., TABLE OF CONTENTS Echinoderm Specialists Addresses Phone (p-) ; Fax (f-) ; e-mail numbers . ........................ .1 Current Research ........•... .34 Information Requests .. .55 Announcements, Suggestions .. • .56 Items of Interest 'Creeping Comatulid' by William Allison .. .57 Obituary - Franklin Boone Hartsock .. • .58 Echinoderms in Literature. 59 Theses and Dissertations ... 60 Recent Echinoderm Publications and Papers in Press. ...................... • .66 New Book Announcements Life and Death of Coral Reefs ......•....... .84 Before the Backbone . ........................ .84 Illustrated Encyclopedia of Fauna & Flora of Korea . • •• 84 Echinoderms: San Francisco. Proceedings of the Ninth IEC. • .85 Papers Presented at Meetings (by country or region) Africa. • .96 Asia . ....96 Austral ia .. ...96 Canada..... • .97 Caribbean •. .97 Europe. .... .97 Guam ••• .98 Israel. 99 Japan .. • •.••. 99 Mexico. .99 Philippines .• . .•.•.• 99 South America .. .99 united States .•. .100 Papers Presented at Meetings (by conference) Fourth Temperate Reef Symposium................................•...... -

Deep Sea Drilling Project Initial Reports Volume 11

21. PLANKTONIC CRINOIDS OF LATE JURASSIC AGE FROM LEG 11, DEEP SEA DRILLING PROJECT Hans Hess, Museum of Natural History, Basel, Switzerland ABSTRACT Remains of saccocomids are described from ten samples of Sites 99, 100, and 105. They embrace a few isolated radials but mainly brachials. The radials and some of the brachials can be assigned to Saccocoma cf. schattenbergi Sieverts-Doreck and S. cf. subornata Sieverts-Doreck (manuscript names). Broken-off bifurcated extensions of Saccocoma cf. quenstedti Sieverts-Doreck (manuscript name) are also quite common in some of the samples. Similar saccocomids have been reported from the Upper Jurassic (Middle to Upper Oxfordian and Lower Kimmeridgian) of Southern Germany and Southeastern France. Most of the remains belong to planktonic saccocomids (S. cf. quenstedti and S. cf. subornata), but S. cf. schattenbergi does not appear to have been purely planktonic. The material may contain some new species but is not rich enough to warrant establishment of new taxa. Through Dr. H. P. Luterbacher I obtained a series of Kimmeridgian) of Southern Germany is being con- samples with isolated skeletal pieces of echinoderms ducted by H. Sieverts-Doreck; the respective publica- for examination. With a few exceptions, the pieces tions are, unfortunately, not yet available. belong to crinoids of the Order Roveacrinida. Since Jurassic roveacrinids ("Saccocoma") are very fre- The crinoids examined here have a very small, stemless quently encountered in thin sections of pelagic lime- calyx (theca), which consists mainly of 5 radials, and stones (Brönnimann, 1955; Colom, 1955; Verniory, mostly delicate brachials which often show processes 1954, 1956; Farinacci and Sirna, 1959; and others), I to facilitate planktonic life. -

Roveacrinids (Crinoidea) from the Mid-Cretaceous of Texas: Ontogeny, Phylogeny, Functional Morphology and Lifestyle

Swiss J Palaeontol DOI 10.1007/s13358-015-0076-z ORIGINAL ARTICLE Roveacrinids (Crinoidea) from the mid-Cretaceous of Texas: ontogeny, phylogeny, functional morphology and lifestyle Hans Hess1 Received: 19 March 2015 / Accepted: 22 April 2015 Ó Akademie der Naturwissenschaften Schweiz (SCNAT) 2015 Abstract New material of known roveacrinids from two two distinct body chambers is unclear. The closely similar Cretaceous sites in Texas is described. Upper Albian strata juvenile cups of Roveacrinus pyramidalis and Poecilocri- at Saginaw Quarry furnished rich material of Poecilocrinus nus latealatus suggest a common origin despite the widely latealatus and Roveacrinus pyramidalis; for these two diverging arm structure. A comparison of Roveacrinus forms cups can be combined with primibrachials and se- pyramidalis with the Triassic somphocrinid Osteocrinus cundibrachials. Some cups of Orthogonocrinus apertus are reveals similar rod-shaped, smooth and tall brachials also present. Juvenile cups of these three species demon- lacking a distinct food groove. Based on their mass oc- strate ontogenetic changes, which are most prominent in currence and wide distribution, species of Osteocrinus P. latealatus. At the adult stage this species has cups with species are thought to have been pelagic. This is substan- dish-like lateral wings; the first primibrachials have an tiated by the presence of cups and rod-shaped brachials in aboral bowl; axillary second primibrachials and proximal Ladinian black shales of southern China. While food of secundibrachials have a wide aboral bowl; and distal bra- species of Poecilocrinus presumably consisted of coccol- chials carry spines. The arms lack pinnules. A pelagic ithophores and planktonic foraminifera, collection and lifestyle with a mouth-up position is assumed. -

Crinoids from Svalbard in the Aftermath of the End-Permian Mass Extinction

Title: Crinoids from Svalbard in the aftermath of the end-Permian mass extinction Author: Mariusz Salamon, Przemysław Gorzelak, Nils-Martin Hanken, Henrik Erevik Riise, Bruno Ferre Citation style: Salamon Mariusz, Gorzelak Przemysław, Hanken Nils-Martin, Riise Henrik Erevik, Ferre Bruno. (2015). Crinoids from Svalbard in the aftermath of the end-Permian mass extinction. "Polish Polar Research" (Vol. 36, no. 3 (2015), s. 225-238), doi 10.1515/popore−2015−0015 vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 225–238, 2015 doi: 10.1515/popore−2015−0015 Crinoids from Svalbard in the aftermath of the end−Permian mass extinction Mariusz A. SALAMON 1, Przemysław GORZELAK2*, Nils−Martin HANKEN 3, Henrik Erevik RIISE 3,4 and Bruno FERRÉ 5 1 Wydział Nauk o Ziemi, Uniwersytet Śląski, ul. Będzińska 60, 41−200 Sosnowiec, Poland <[email protected]> 2 Instytut Paleobiologii, Polska Akademia Nauk, ul. Twarda 51/55, 00−818 Warszawa, Poland <[email protected]> * corresponding author 3 Department of Geology, UiT – The Arctic University of Norway, NO−9037 Tromsø, Norway <nils−[email protected]> 4 Present address: Halliburton, Sperry Drilling, P.O. Box 200, NO−4065 Stavanger, Norway <[email protected]> 5 Dame du Lac 213, 3 rue Henri Barbusse, F−76300 Sotteville−lès−Rouen, France <[email protected]> Abstract: The end−Permian mass extinction constituted a major event in the history of cri− noids. It led to the demise of the major Paleozoic crinoid groups including cladids, disparids, flexibles and camerates. It is widely accepted that a single lineage, derived from a late Paleo− zoic cladid ancestor (Ampelocrinidae), survived this mass extinction. -

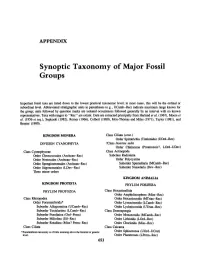

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida -

The Upper Jurassic of Europe: Its Subdivision and Correlation

The Upper Jurassic of Europe: its subdivision and correlation Arnold Zeiss In the last 40 years, the stratigraphy of the Upper Jurassic of Europe has received much atten- tion and considerable revision; much of the impetus behind this endeavour has stemmed from the work of the International Subcommission on Jurassic Stratigraphy. The Upper Jurassic Series consists of three stages, the Oxfordian, Kimmeridgian and Tithonian which are further subdivided into substages, zones and subzones, primarily on the basis of ammonites. Regional variations between the Mediterranean, Submediterranean and Subboreal provinces are discussed and correlation possibilities indicated. The durations of the Oxfordian, Kimmeridgian and Tithonian Stages are reported to have been 5.3, 3.4 and 6.5 Ma, respectively. This review of the present status of Upper Jurassic stratigraphy aids identification of a num- ber of problems of subdivision and definition of Upper Jurassic stages; in particular these include correlation of the base of the Kimmeridgian and the top of the Tithonian between Submediterranean and Subboreal Europe. Although still primarily based on ammonite stratigraphy, subdivision of the Upper Jurassic is increasingly being refined by the incorporation of other fossil groups; these include both megafossils, such as aptychi, belemnites, bivalves, gastropods, brachiopods, echino- derms, corals, sponges and vertebrates, and microfossils such as foraminifera, radiolaria, ciliata, ostracodes, dinoflagellates, calcareous nannofossils, charophyaceae, dasycladaceae, spores and pollen. Important future developments will depend on the detailed integration of these disparate biostratigraphic data and their precise combination with the abundant new data from sequence stratigraphy, utilising the high degree of stratigraphic resolution offered by certain groups of fos- sils. -

4. Arbeitstreffen Deutschsprachiger Echinodermenforscher Wien, Oktober 08

4. Arbeitstreffen deutschsprachiger Echinodermenforscher Wien, Oktober 08 4. Arbeitstreffen deutschsprachiger Echinodermenforscher, Wien, Okt. 08 4th Workshop of German & Austrian Echinoderm Research 4. Arbeitstreffen deutschsprachiger Echinodermenforscher 4th Workshop of German & Austrian Echinoderm Research 24.-26. October 2008 ABSTRACTS Andreas Kroh & Brigitta Schmid Naturhistorisches Museum Wien 4. Arbeitstreffen deutschsprachiger Echinodermenforscher 4th Workshop of German & Austrian Echinoderm Research Impressum Eigentümer, Herausgeber und Verleger: © 2008 Natuhistorisches Museum Wien Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Für den Inhalt der Beiträge sind die Autoren verantwortlich. Redaktion: Naturhistorisches Museum Wien Burgring 7, A-1010 Wien, Österreich (Austria) Tel.: +43 (1) 521 77 / 576 (Kroh); +43 (1) 521 77 / 564 (Schmid) Fax: +43 (1) 521 77 / 459 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Redaktionelle Bearbeitung (EDV, Layout, Grafik): Andreas Kroh Umschlagentwurf: Andreas Kroh Titelbild: Coelopleurus (Keraiophorus) exquisitus COPPARD & SCHULTZ, 2006; Neukaledonien (NHMW 2005z0277/0016; Photo von Alice SCHUMACHER, NHM Wien). 24.-26. October 2008 iii 4. Arbeitstreffen deutschsprachiger Echinodermenforscher 4th Workshop of German & Austrian Echinoderm Research Inhalt Encrinus sp. cf. E. robustus (Crinoidea, Encrinidae) aus dem Unteren Muschelkalk von Niedersachsen (Poster) Ulrich Bielert, Friedrich Bielert & Hans Hagdorn...........................................1 Classification of pre- and postmortem -

Early Cretaceous (Valanginian) Sea Lilies (Echinodermata, Crinoidea) from Poland

1661-8726/09/010077-12 Swiss J. Geosci. 102 (2009) 77–88 DOI 10.1007/s00015-009-1312-6 Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, 2009 Early Cretaceous (Valanginian) sea lilies (Echinodermata, Crinoidea) from Poland MARIUSZ A. SALAMON Key words: Crinoidea, isocrinids, Early Cretaceous, Poland, taxonomy, palaeobiogeography ABSTRACT Valanginian strata in central epicratonic Poland have recently yielded crinoids, the southernmost Tethyan regions of Poland (Pieniny Klippen Belt and Tatra not previously recorded from the area. The fauna comprises isocrinids (Bala- Mountains). The current study demonstrates their occurrence in central epi- nocrinus subteres, B. gillieroni, “Isocrinus?” lissajouxi), millericrinids (Apiocrin- cratonic Poland, and suggests that many Jurassic to Cretaceous stalked crinoid ites sp.) and comatulids (Comatulida indet.). For comparison, a few samples taxa (mainly isocrinids) predominated in the shallow-water settings of this area. of isocrinids from Valanginian strata of Hungary (Tethyan province) were Thus, the hypothesis of migration (at least from mid-Cretaceous onwards) to also analysed. The isocrinids, cyrtocrinids and roveacrinids (sensu Rasmussen deep-water areas, as a response to an increase of the number of predators dur- 1978 inclusive of Saccocoma sp.) were already known from the Valanginian of ing the Mesozoic marine revolution, seems not to be universally applicable. Introduction The present study documents Early Cretaceous crinoids from the Polish part of the Tethyan Realm, which are more nu- Current knowledge of the Early Cretaceous crinoids from extra- merous and taxonomically diverse than previously assumed. In Carpathian Poland is very limited. Pisera (1984) recorded only particular this study 1) characterises the crinoid assemblages roveacrinids (Styracocrinus peracutus) and comatulids (Gleno- from epicratonic and Tethyan Poland, and 2) discusses their pa- tremites sp.) from the Barremian-Cenomanian of northern Po- laeobiogeography and palaeoecology. -

20. Paleoecology and Stratigraphy of Jurassic Abyssal Foraminifera in the Blake-Bahama Basin, Deep Sea Drilling Project Site 5341

20. PALEOECOLOGY AND STRATIGRAPHY OF JURASSIC ABYSSAL FORAMINIFERA IN THE BLAKE-BAHAMA BASIN, DEEP SEA DRILLING PROJECT SITE 5341 F. M. Gradstein, Geological Survey of Canada, Bedford Institute of Oceanography, Dartmouth, N. S. B2Y 4A2, Canada ABSTRACT At Site 534, Blake-Bahama Basin, 66 brownish to olive green to gray black shale samples from Cores 127 to 70, of the middle Callovian-Valanginian, contain an assemblage of foraminifers with 36 calcareous taxa in 9 families and 35 agglutinated taxa in 8 families. The average number of taxa per sample is about 5, with a spread of 0 to 19 and a mode of about 8. Sample weight (10-50 g) is not correlated to species diversity and to specimen abundance, which means that a better recovery tool is more rather than bigger samples per core. R-mode cluster analysis using Jaccard and Dice coefficients of variation on 25 taxa occurring in 5 or more samples show a low level of association. One cluster includes the Kimmeridgian, carbonate-rich environment assemblage with Lenticulina quenstedti, Ophthalmidium carinatum, Neobulimina atlantica n. sp., and Epistomina aff. uhligi. Three clusters comprise stratigraphically persistent taxa of the genera Reophax, Bigenerina, Bathysiphon, Glomospira, Glo- mospirella, Lenticulina, Rhizammina, Psammosphaera, Dentalina, Lagena, Marginulina, Pseudonodosaria, and Tro- chammina. Strikingly similar Jurassic assemblages at other Atlantic and Indian oceans sites, which also backtrack to ~ 3-km water depth, show that the Jurassic abyssal fauna principally consists of small-sized agglutinated taxa in 8 or so families, small-sized nodosariids in a dozen or so genera, and variable numbers of epistominids, ophthalminids, spirri- linids, and turrilinids.