Special-Sessions-1999-37940-600-21

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fortnight Nears the End

World Bridge Series Championship Philadelphia Pennsylvania, USA 1st to 16th October D B 2010 aily ulletin O FFICIAL S PONSOR Co-ordinator: Jean-Paul Meyer • Chief Editor: Brent Manley • Editors: Mark Horton, Brian Senior, Phillip Alder, Barry Rigal, Jan Van Cleef • Lay Out Editor: Akis Kanaris • Photographer: Ron Tacchi Issue No. 14 Friday, 15 October 2010 FORTNIGHT NEARS THE END These are the hard-working staff members who produce all the deals — literally thousands — for the championships Players at the World Bridge Series Championships have been In the World Junior Championship, Israel and France will start at it for nearly two weeks with only one full day left. Those play today for the Ortiz-Patino Trophy, and in the World Young- who have played every day deserve credit for their stamina. sters Championship, it will be England versus Poland for the Consider the players who started on opening day of the Damiani Cup. Generali Open Pairs on Saturday nearly a week ago. If they made it to the final, which started yesterday, they will end up playing 15 sessions. Contents With three sessions to go, the Open leaders, drop-ins from the Rosenblum, are Fulvio Fantoni and Claudio Nunes. In the World Bridge Series Results . .3-5 Women’s Pairs, another pair of drop-ins, Carla Arnolds and For Those Who Like Action . .6 Bep Vriend are in front. The IMP Pairs leaders are Joao-Paulo Campos and Miguel Vil- Sting in the Tail . .10 las-Boas. ACBL President Rich DeMartino and Patrick McDe- Interview with José Damiani . .18 vitt are in the lead in the Hiron Trophy Senior Pairs. -

From Custom to Code. a Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football

From Custom to Code From Custom to Code A Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football Dominik Döllinger Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Humanistiska teatern, Engelska parken, Uppsala, Tuesday, 7 September 2021 at 13:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Associate Professor Patrick McGovern (London School of Economics). Abstract Döllinger, D. 2021. From Custom to Code. A Sociological Interpretation of the Making of Association Football. 167 pp. Uppsala: Department of Sociology, Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-506-2879-1. The present study is a sociological interpretation of the emergence of modern football between 1733 and 1864. It focuses on the decades leading up to the foundation of the Football Association in 1863 and observes how folk football gradually develops into a new form which expresses itself in written codes, clubs and associations. In order to uncover this transformation, I have collected and analyzed local and national newspaper reports about football playing which had been published between 1733 and 1864. I find that folk football customs, despite their great local variety, deserve a more thorough sociological interpretation, as they were highly emotional acts of collective self-affirmation and protest. At the same time, the data shows that folk and early association football were indeed distinct insofar as the latter explicitly opposed the evocation of passions, antagonistic tensions and collective effervescence which had been at the heart of the folk version. Keywords: historical sociology, football, custom, culture, community Dominik Döllinger, Department of Sociology, Box 624, Uppsala University, SE-75126 Uppsala, Sweden. -

Hard Knocks in Beijing

Co-Ordinator: Jean-Paul Meyer, Chief Editor: Brent Manley, Layout Editor: George Hatzidakis, WebEditor: Akis Kanaris, Photographer: Ron Tacchi, Editors: Phillip Alder, Mark Horton, Barry Rigal Bulletin 10 - Tuesday, 14 October 2008 HARD KNOCKS IN BEIJING The WBF Meeting of Congress earlier in the tournament. See page 10 for minutes of the meeting. Reality set in for the Cinderella team from Romania, as the four- man squad was dispatched with relative ease by England in the Open Today’s series. The Romanians weren’t the only losers, of course. Eleven other teams were sent to the sidelines in the quarterfinal rounds of Schedule the Open, Women’s and Seniors. 11.00 Open - Women - Senior The German women seemed unstoppable in the round robin and Teams, S-Final, 1st Session then blasted Brazil in the round of 16. In their quarterfinal match 14.20 Open - Women - Senior with China, the Germans trailed by only 2 IMPs going into the last Teams, S-Final, 2nd Session set, but were trounced over the final 16 boards 48-2 to exit the 17.10 Open - Women - Senior event. Teams, S-Final, 3rd Session The USA women were in a nail-biter with Denmark until they 10.30 - 20.00 pulled away over the last few boards. Transnational Mixed Teams, Two days of semi-final play begin today. The key matches look to be Swiss Matches 8-12 Italy-Norway in the Open and China-USA in the Women’s. World Bridge Games Beijing, China OPEN TEAMS RESULTS - Q-Final Match 1st-3rd Session 4th Session 5th Session 6th Session Total 1 Poland Italy 69 -106 38 - 23 33 - 49 33 - 32 173 -210 -

Read Book the Beautiful Game?: Searching for the Soul of Football

THE BEAUTIFUL GAME?: SEARCHING FOR THE SOUL OF FOOTBALL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David Conn | 448 pages | 04 Aug 2005 | Vintage Publishing | 9780224064361 | English | London, United Kingdom The Beautiful Game?: Searching for the Soul of Football PDF Book The latest commerical details, groundbreaking interviews and industry analysis, free, straight to your inbox. Since then, while the rules of the sport have gradually evolved to the point where VAR is now used, for example , football has more or less retained the same overall constitution and objectives. Racism has been a stain on the soul of soccer for generations but a series of high-profile incidents in recent years has prompted calls for tougher action from football's governing bodies. Even at amateur junior level, I saw the way presidents of clubs manipulated funds to get their senior mens teams promoted, buying players, dirty deals to pay a top striker etc. A number of different rule codes existed, such as the Cambridge rules and the Sheffield rules, meaning that there was often disagreement and confusion among players. Showing To ask other readers questions about The Beautiful Game? Mark rated it it was amazing Apr 21, Follow us on Twitter. It makes you wonder if the Football Association are fit to be the governing body of the sport. Watch here UEFA president Michel Platini explains why any player or official guilty of racism will face a minimum match ban. Add your interests. Leading international soccer player Mario Balotelli has had enough -- the AC Milan striker has vowed to walk off the pitch next time he is racially abused at a football game. -

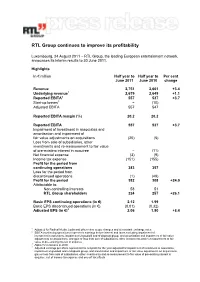

RTL Group Continues to Improve Its Profitability

RTL Group continues to improve its profitability Luxembourg, 24 August 2011 − RTL Group, the leading European entertainment network, announces its interim results to 30 June 2011. Highlights In € million Half year to Half year to Per cent June 2011 June 2010 change Revenue 2,751 2,661 +3.4 Underlying revenue1 2,679 2,649 +1.1 Reported EBITA2 557 537 +3.7 Start-up losses3 − (10) Adjusted EBITA 557 547 Reported EBITA margin (%) 20.2 20.2 Reported EBITA 557 537 +3.7 Impairment of investment in associates and amortisation and impairment of fair value adjustments on acquisitions (20) (5) Loss from sale of subsidiaries, other investments and re-measurement to fair value of pre-existing interest in acquiree − (11) Net financial expense (3) (9) Income tax expense (151) (155) Profit for the period from continuing operations 383 357 Loss for the period from discontinued operations (1) (49) Profit for the period 382 308 +24.0 Attributable to: Non-controlling interests 58 51 RTL Group shareholders 324 257 +26.1 Basic EPS continuing operations (in €) 2.12 1.99 Basic EPS discontinued operations (in €) (0.01) (0.32) Adjusted EPS (in €)4 2.06 1.90 +8.4 1 Adjusted for Radical Media, Ludia and other minor scope changes and at constant exchange rates 2 EBITA (continuing operations) represents earnings before interest and taxes excluding impairment of investment in associates, impairment of goodwill and of disposal group, and amortisation and impairment of fair value adjustments on acquisitions, and gain or loss from sale of subsidiaries, other investments -

Zur Ökonomik Von Spitzenleistungen Im Internationalen Sport

Zur Ökonomik von Spitzenleistungen im internationalen Sport Martin-Peter Büch, Wolfgang Maennig und Hans-Jürgen Schulke (Hrsg.) EDITION HWWI Hamburg University Press Zur Ökonomik von Spitzenleistungen im internationalen Sport Reihe Edition HWWI Band 3 Zur Ökonomik von Spitzenleistungen im internationalen Sport Herausgegeben von Martin-Peter Büch, Wolfgang Maennig und Hans-Jürgen Schulke Hamburg University Press Verlag der Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky Impressum Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Die Online-Version dieser Publikation ist auf den Verlagswebseiten frei verfügbar (open access). Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek hat die Netzpublikation archiviert. Diese ist dauerhaft auf dem Archivserver der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek verfügbar. Open access über die folgenden Webseiten: Hamburg University Press – http://hup.sub.uni-hamburg.de PURL: http://hup.sub.uni-hamburg.de/HamburgUP/HWWI3_Oekonomik Archivserver der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek –https://portal.dnb.de/ ISBN 978-3-937816-87-6 ISSN 1865-7974 © 2012 Hamburg University Press, Verlag der Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky, Deutschland Produktion: Elbe-Werkstätten GmbH, Hamburg, Deutschland http://www.ew-gmbh.de Dieses Werk ist unter der Creative Commons-Lizenz „Namensnennung- Keine kommerzielle Nutzung-Keine -

International Olympic Committee, Lausanne, Switzerland

A PROJECT OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE, LAUSANNE, SWITZERLAND. WWW.OLYMPIC.ORG TEACHING VALUESVALUES AN OLYYMPICMPIC EDUCATIONEDUCATION TOOLKITTOOLKIT WWW.OLYMPIC.ORG D R O W E R O F D N A S T N E T N O C TEACHING VALUES AN OLYMPIC EDUCATION TOOLKIT A PROJECT OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE, LAUSANNE, SWITZERLAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The International Olympic Committee wishes to thank the following individuals for their contributions to the preparation of this toolkit: Author/Editor: Deanna L. BINDER (PhD), University of Alberta, Canada Helen BROWNLEE, IOC Commission for Culture & Olympic Education, Australia Anne CHEVALLEY, International Olympic Committee, Switzerland Charmaine CROOKS, Olympian, Canada Clement O. FASAN, University of Lagos, Nigeria Yangsheng GUO (PhD), Nagoya University of Commerce and Business, Japan Sheila HALL, Emily Carr Institute of Art, Design & Media, Canada Edward KENSINGTON, International Olympic Committee, Switzerland Ioanna MASTORA, Foundation of Olympic and Sport Education, Greece Miquel de MORAGAS, Centre d’Estudis Olympics (CEO) Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB), Spain Roland NAUL, Willibald Gebhardt Institute & University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany Khanh NGUYEN, IOC Photo Archives, Switzerland Jan PATERSON, British Olympic Foundation, United Kingdom Tommy SITHOLE, International Olympic Committee, Switzerland Margaret TALBOT, United Kingdom Association of Physical Education, United Kingdom IOC Commission for Culture & Olympic Education For Permission to use previously published or copyrighted -

Bermuda Bowl

Co-ordinator: Jean-Paul Meyer – Editor: Brent Manley – Assistant Editors: Mark Horton & Brian Senior Proof-Reader: Phillip Alder – Layout Editor: George Georgopoulos – Photographer: Ron Tacchi Issue No. 5 Thursday, 27 October 2005 THE BEAT GOES ON USA1 v Poland on vugraph Three days remain in the qualifying rounds of the Bermuda in close pursuit. Bowl,Venice Cup and Seniors Bowl, meaning that the clock is In the Seniors Bowl, Indonesia took over the top qualifying ticking for teams with hopes of continuing to play when the spot after the previous leaders, the Netherlands, were knockout phases begin. thumped by USA1, 84-16. In the Bermuda Bowl, Italy maintained their stranglehold on At the halfway point of qualifying in the World Computer first place in the round-robin after 12 rounds of play – and the Bridge Championships,Wbridge5 (France) held a narrow lead Netherlands made a move with a dismantling of the USA2 over the defending champion, Jack (Netherlands). team that had been playing so well. The Americans held on to fourth place despite the 93-6 drubbing. VUGRAPH MATCHES In the Venice Cup, China's once-impressive lead – more than a match – had shrunk to barely more than 7 VPs,with France Bermuda Bowl – ROUND 13 – 10.00 Egypt v Italy Welcome, Venice Cup Bowl – ROUND 14 – 14.00 Marc Hodler (Boards 1-16) China v England The 9th World Bridge Championships bid welcome to Bermuda Bowl – ROUND 14 – 14.00 Marc Hodler, president of the WBF World Congress and (Boards 17-20) a life member of the International Olympic Committee. -

“Temple of My Heart”: Understanding Religious Space in Montreal's

“Temple of my Heart”: Understanding Religious Space in Montreal’s Hindu Bangladeshi Community Aditya N. Bhattacharjee School of Religious Studies McGill University Montréal, Canada A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts August 2017 © 2017 Aditya Bhattacharjee Bhattacharjee 2 Abstract In this thesis, I offer new insight into the Hindu Bangladeshi community of Montreal, Quebec, and its relationship to community religious space. The thesis centers on the role of the Montreal Sanatan Dharma Temple (MSDT), formally inaugurated in 2014, as a community locus for Montreal’s Hindu Bangladeshis. I contend that owning temple space is deeply tied to the community’s mission to preserve what its leaders term “cultural authenticity” while at the same time allowing this emerging community to emplace itself in innovative ways in Canada. I document how the acquisition of community space in Montreal has emerged as a central strategy to emplace and renew Hindu Bangladeshi culture in Canada. Paradoxically, the creation of a distinct Hindu Bangladeshi temple and the ‘traditional’ rites enacted there promote the integration and belonging of Bangladeshi Hindus in Canada. The relationship of Hindu- Bangladeshi migrants to community religious space offers useful insight on a contemporary vision of Hindu authenticity in a transnational context. Bhattacharjee 3 Résumé Dans cette thèse, je présente un aperçu de la communauté hindoue bangladaise de Montréal, au Québec, et surtout sa relation avec l'espace religieux communautaire. La thèse s'appuie sur le rôle du temple Sanatan Dharma de Montréal (MSDT), inauguré officiellement en 2014, en tant que point focal communautaire pour les Bangladeshis hindous de Montréal. -

Sports Analytics Algorithms for Performance Prediction

Sports Analytics Algorithms for Performance Prediction Chazan – Pantzalis Victor SID: 3308170004 SCHOOL OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Data Science DECEMBER 2019 THESSALONIKI – GREECE I Sports Analytics Algorithms for Performance Prediction Chazan – Pantzalis Victor SID: 3308170004 Supervisor: Prof. Christos Tjortjis Supervising Committee Members: Dr. Stavros Stavrinides Dr. Dimitris Baltatzis SCHOOL OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Data Science DECEMBER 2019 THESSALONIKI – GREECE II Abstract Sports Analytics is not a new idea, but the way it is implemented nowadays have brought a revolution in the way teams, players, coaches, general managers but also reporters, betting agents and simple fans look at statistics and at sports. Machine Learning is also dominating business and even society with its technological innovation during the past years. Various applications with machine learning algorithms on core have offered implementations that make the world go round. Inevitably, Machine Learning is also used in Sports Analytics. Most common applications of machine learning in sports analytics refer to injuries prediction and prevention, player evaluation regarding their potential skills or their market value and team or player performance prediction. The last one is the issue that the present dissertation tries to resolve. This dissertation is the final part of the MSc in Data Science, offered by International Hellenic University. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my Supervisor, Professor Christos Tjortjis, for offering his valuable help, by establishing the guidelines of the project, making essential comments and providing efficient suggestions to issues that emerged. -

Educating Communities for a Sustainable Future – Do Large-Scale Sporting Events Have a Role?

Educating communities for a sustainable future – Do large-scale sporting events have a role? Robert James Harris BA, MBus., Dip. Teach. i Educating communities for a sustainable future – Do large-scale sporting events have a role? Robert James Harris BA, MBus., Dip. Teach. Being a thesis submitted to the University of Technology, Sydney in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctor of Education, June 2010 ii Certificate of Authorship and Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of the requirements of a degree and that the work is the original work of the candidate except where sources are acknowledged. Signature............................................................................................................ iii Acknowledgements I am grateful to the people whose support made the writing of this thesis possible. In particular I wish to thank the following: First and foremost, I would like to thank the case study informants who generously gave of their time, and provided their recollections and forthright perspectives on the process of leveraging either the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games or Melbourne 2006 Commonwealth Games for education for sustainable development purposes. I am deeply indebted to my supervisor Professor David Boud and co-supervisor Professor Christine Toohey, who provided guidance, support and professional mentoring over an extended period. I am particularly indebted to David for his ability to steer this study in an area where research was absent, his efforts to encourage critical self-reflection, and his ability to find time when there likely wasn’t any to quickly turn around material that was submitted. -

2001/2002 Annual Report

2001/2002 Annual Report Thanks to our Principle Strategic Partner Mission and Corporate Values Mission Australian Canoeing is the national body responsible for the management, coordination, development and promotion of paddle sports in Australia. It represents the interests of its members to government, the public and the International Canoe Federation. Australian Canoeing will provide National leadership and a national framework for harnessing the energies of the many canoeing people and organisations throughout Australia with the aim of building the business of canoeing for the benefit of all. Corporate Values Australian Canoeing is committed to the provision of a high standard of competition, safety, and opportunity for participation in paddle sports in Australia. It aims to provide all members with fair competition, access to high standard facilities and equity in participation at all levels. The work of Australian Canoeing over the next four years and beyond will demonstrate a commitment to: Leadership The board, committees and management of Australian Canoeing will provide leadership and direction for the national good. Cooperation, The achievement of national priorities and common partnerships and linkages goals will depend on working cooperatively and in partnership with many organisations and maintaining links with all levels of canoeing. Business best practice The future viability and growth of canoeing will be and client focus built upon the application of business principles, an understanding of the needs and wants of clients and providing services to member organisations and individuals accordingly. Cost effectiveness The internal operations and service provision functions of Australian Canoeing will be undertaken on a demonstrable cost-effective basis.