Melvin Tolson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top Things to Do in Norman

An Insider’s Guide to Visiting Norman, Oklahoma For free maps, visitor's guides, help with accommodations, lots of good advice on the area: Norman Convention and Visitors Bureau Most bold listings below contain Norman Ranked 6th Best Place to live links to web pages! Check Live to live in in the U.S. by Money Magazine, 2008 Our favorite things to do in Norman/Oklahoma City Stroll around the OU Campus! National Weather Center (public tours M,W,F 1 p.m.) Includes NOAA’s Storm Prediction Center, the Norman National Weather Service Forecast Office, National Severe Storms Laboratory, University of Oklahoma School of Meteorology, the NWC observation deck, classroom and laboratory facilities. Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History The largest university-based museum in the country, this 50,000-square-foot museum features five outstanding galleries that depict more than 300 million years of Oklahoma's natural history. Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art “The Fred,” 555 Elm Ave. Located right across the street from Catlett Music Center and the Music Practice Building! The Weitzenhoffer Collection in the Museum includes works by such artists as Degas, Gauguin, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, Toulouse- Lautrec, Van Gogh, Vuillard, and others. Not to be missed, and right across the street from Catlett! Oklahoma City Art Museum Largest Dale Chihuly glass exhibit in the world – truly exceptional. Suggest checking out the excellent food in the Museum Cafe before or after your visit. Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum (bombing memorial) 620 N. Harvey Ave., Oklahoma City Bricktown Entertainment District, Great restaurants, entertainment venues and ride the Bricktown water taxis on the canal in historic downtown Oklahoma City Some Norman restaurants we enjoy: Benvenuti’s, 105 W. -

The Way of Life

THE SoonerWAY OF LIFE The Sooner WAY OF LIFE NORMAN AT A GLANCE The University of Oklahoma’s 15% 116K below national 44.3% $66K $141K $185K beautiful, bustling campus is nestled average in the heart of Norman, the state’s third largest city. Norman combines Population Cost Bachelor’s Median family Average OU Median home the charm of a college town, the of living degrees or income faculty salary sales price higher and benefits sophistication of a cosmopolitan city and the history and culture of the American West. AFFORDABILITY + [COMMUNITY, DIVERSITY AND CULTURE] = HIGH QUALITY OF LIFE Faculty who come to OU for outstanding career opportunities are captivated by Norman and its easy OKLAHOMA AT A GLANCE way of living. They stay because Norman is a culturally diverse community where balancing work and achievement with family and 3.86M 39 400+ 60.5°F recreation is, quite simply, our way of life – the Sooner way of life. Population Federally- Miles of Average recognized Route 66 annual tribal nations temperature Quick access from Oklahoma City’s Will Rogers World Airport to Kansas City, Chicago, Dallas, Houston, New Orleans, Denver and many other cities Community AND NEIGHBORHOODS Norman’s neighborhoods offer a wide variety of old and new Norman’s two city-designated historic preservation districts flank the east – from campus homes to rural estates to modern designs. Neighborhood, and west sides of the university. Most of 300-plus homes were built between community and local government organizations work together to address 1915 and 1938, represent almost every architectural style prevalent during beautification, historic preservation and public safety issues. -

City of Edmond Street Names List Dir

City of Edmond Street Names List Dir. Street Name Addition Name Map Code E 1ST STREET ORIGINAL TOWNSITE E-9 W 1ST STREET ORIGINAL TOWNSITE D-9 E 2ND STREET E-P 9 W 2ND STREET D 8/9 E 3RD STREET ORIGINAL TOWNSITE D-E 8 W 3RD STREET ORIGINAL TOWNSITE D 8 E 4TH STREET EB TOWNSENDS D-E 8 W 4TH STREET EB TOWNSENDS D 8 E 5TH STREET OSBORNES ROSEWOOD D-G 8 W 5TH STREET OSBORNES ROSEWOOD D 8 E 6TH STREET PATTONS D-E 8 W 6TH STREET PATTONS D 8 E 7TH STREET PATTONS/ INGLESIDE D-E 8 W 7TH STREET PATTONS/ INGLESIDE C-D 8 E 8TH STREET SOUTH PARK D-E 8 W 8TH STREET SOUTH PARK D 8 E 9TH STREET PATTENS/SUNSET HEIGHTS D-E 7 W 9TH STREET PATTENS/SUNSET HEIGHTS D 7 E 10TH STREET PLAZA BOULEVARD PLACE E 7 W 10TH PLACE APPLE VILLAGE D 8 E 10TH STREET INGLESIDE/APPLE VILLAGE D-E 7 W 10TH STREET INGLESIDE/APPLE VILLAGE D 7 E 11TH STREET OAKSLAWN D-E 7 E 12TH STREET CAMPBELLS TERRACE D-E 7 E 13TH STREET FLEETWOOD TERRACE D-E 7 E 14TH STREET FLEETWOOD TERRACE E 7 E 15TH STREET B-D 6/7 W 15TH STREET D-P 6/7 W 18TH STREET SIGNAL RIDGE D 6 E 19TH STREET CANYON PARK F 6 E 21ST STREET HENDERSON HILLS D 6 E 22ND STREET HENDERSON HILLS D 6 E 23RD STREET ELWOOD HEIGHTS D 6 E 26TH STREET PARKER ESTATES E 5 E 27TH PLACE PARKER ESTATES E 5 E 27TH STREET HENDERSON ESTATES E-G 5/6 E 28TH STREET PARKER ESTATES E 5 E 29TH STREET NICHOLSONS E 5 E 30TH STREET HENDERSON ESTATES D-G 5 E 31ST STREET SOUTHERN HILLS E 5 E 32ND STREET ELWOOD HEIGHTS D-G 5 E 32ND STREET THORNBROOKE MANOR F 5 E 33RD STREET B-D 5 W 33RD STREET D-N 5 E 34TH STREET SMILING HILLS E 4 E 35TH STREET WHISPERING HEIGHTS E 4 E 37TH STREET CHEYENNE RIDGE/SPRING HILL F 4 E 37TH COURT SPRING HILL F 4 E 40TH STREET HARRIS TALL OAKS G 3 E 44TH STREET EDMOND OAKS G 3 ABADAN COURT ABADAN CREEK D 8 ABADAN DRIVE ABADAN CREEK D 8 3/10/2021 City of Edmond Street Names List Dir. -

OKAPA Newsletter

Volume 5, Issue 1 Winter/Spring 2007 President’s Notes John Dugan, AICP On my office wall What does that which focuses on mixed in Oklahoma City is a map mean to us today in Okla- use and mixed income that covers more than 1400 homa? In my opinion, it neighborhoods in a pedes- square miles of central means negotiating with trian-oriented design Oklahoma. Almost every developers and neighbor- theme, nicely address these square mile shows some hoods to accommodate the ideas. type of development. highest density possible I encourage all As planners for concurrent with the highest Oklahoma planners to look the next generation we quality possible on every closely at the various New should be asking ourselves new subdivision and multi- Urban websites and publi- and our clients and custom- family development. It cations for ideas and strate- ers “is current low density means fostering mixed-use gies to better prepare our and intensity of develop- as the preferred develop- state for a sustainable fu- ment sustainable for the ment option, with densities ture. future?” high enough to sustain tran- And coming up is We are planning sit service whenever it is a City Planning Workshop now in OKC for a mini- finally available. And it organized by the Oklahoma mum growth of 70,000 challenges us as planners to Municipal League on Fri- additional residents and 50 design job/housing relation- day, May 4, at OSU-OKC million square feet of com- ships that work in terms of where the principles of mercial/industrial space both property values and New Urbanism will be dis- ASSOCIATION over the next 10 years. -

Architectural/Historic Intensive Level Survey of Certain Parts of the City of Norman, Oklahoma Survey Report #40-88-30123.003

I . ARCHITECTURAL/HISTORIC INTENSIVE LEVEL SURVEY OF CERTAIN PARTS OF THE CITY OF NORMAN, OKLAHOMA SURVEY REPORT #40-88-30123.003 University of Oklahoma College of Architecture Design/Research Center Maryjo Meacham - Project Manager Dr. Thomas Selland - Co-Investigator Michelle Maahs - Student Project Manager Steve Rhodes - Graduate Research Assistant Julie Wackler - Graduate Research Assistant Theresa Coffman - Graduate Research Assistant Xavier Leung - Research Assistant Prepared for: Oklahoma Historical Society State Historic Preservation Office Wiley Post Historical Building Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73015 1988 - 1989 SURVEY REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE ABSTRACT OF REPORT i ONE INTRODUCTION l TWO PROJECT OBJECTIVES 3 THREE DESCRIPTION OF AREA SURVEYED 5 FOUR RESEARCH DESIGN & METHODOLOGY 8 Research Design 8 Methodology 10 Types of Properties Evaluated 12 FIVE RESULTS 13 Summary of Results 13 Types of Properties Identified 16 Eligible Individual Properties 20 Eligible Districts 22 Campus Corner Historic District 24 De Barr Historic District 35 Original Townsite Historic District 41 Silk Stocking Historic District 48 Ineligible Districts 56 Trout District 57 SIX SUMMARY 62 ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY APPENDIX A. Recommendations B. List of Campus Corner Buildings LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS Table 1 Number of Blocks, Acres and Structures Located in the Survey Areas/Historic Districts page 15 Maps of the Survey Areas/Historic Districts 1 Campus Corner District 2 De Barr District 3 Original Townsite District 4 Silk Stocking District 5 Trout District 3 ABSTRACT OF REPORT The report for the "Architectural/Historic Intensive Level Survey of Certain Parts of the City of Norman, Oklahoma" project contains seven chapters outlining the objectives of the project, research design employed during the project, survey strategy, methodology, types of properties to be evaluated, specific properties identified, districts with National Register potential, areas without historic properties, summary/recommendations, and an annotated bibliography. -

Flavors & Football

August 2017 • Issue 8 • Volume 16 Gasso on faith, family & a life in sport Flavors & Football Taste of Norman returns Heartland Haven: Sam Noble’s Centennial Prairie Love Lindsey Riley welcomes brighter days TAKES THE REIGNS A mortgage partner who can fund all my real estate needs is unrealistic. right here. LOAN PROGRAMS First United has a loan to serve your Conventional/Jumbo Loans specific needs. Our extensive loan FHA/VA/USDA Loans Sec. 184 Native American Loans options enable us to fund a wide Construction to Permanent Loans variety of loans at competitive rates Refinance & Refinance Loans — under one roof. SPECIAL PROGRAMS Doctor Loan Program One-Time Close & Two-Time Close Let me find you the right loan! SPECIAL OFFERS Civil, Military, & Teacher Loan Specials Cheryl Jenkins Koontz Mortgage Loan Consultant NMLS #462274 405-364-0101 [email protected] For Fast & Easy Prequalification: https://cjenkins.firstunitedteam.comFor Fast & Easy Prequalification: First United Bank Mortgage Group, NMLS 400025. All loans subject to 570 24th Avenue NW program guidelines and final underwriting approval. Norman, OK 73069 Banking • Mortgage • Insurance • Investments EARN 11X ENTRIES ON SUNDAYS AND MONDAYS TO DRIVE HOME YOUR NEW, IMMACULATE PIECE OF GERMAN ENGINEERING: A BRAND-NEW 2018 AUDI Q3. JUST MAKE SURE YOU’RE HERE TO START IT UP SATURDAY, AUGUST 26 AT 11 PM. 405.322.6000 • WWW.RIVERWIND.COM I-35 AT HIGHWAY 9 WEST, NORMAN, OK GAMBLE RESPONSIBLY 1.800.522.4700 SATURDAYS WIN A SHARE OF $500 SATURDAYS 7 PM-11 PM PLAY ANY ELECTRONIC GAME ON SATURDAYS FOR YOUR CHANCE TO WIN. -

Route Schedule and Transit Guide Norman, Oklahoma 2016

Route Schedule and Transit Guide Norman, Oklahoma 2016 Updated 1/2016 Want to park for free? Place this sticker on the back of your OU ID and follow the steps below! PARK: Free Parking is available at the Lloyd Noble Center. PARK FREE 2900 S Jenkins Ave RIDE: Let the shuttle take you @ LNC! to campus, rain or shine. Shuttle every 10 minutes! VISIT: CART’s website for maps, CART GPS and more! Welcome rideCARTDownload.com CART’s to CART brand new app! download our new app! All buses feature wifi! Located at the Theta M. Dempsey Transportation Operations Center How to ride the bus 510 E. Chesapeake St. • Arrive at stop 5 minutes early and check bus Norman, OK 73019-5128 route name before boarding. • Keep aisles clear, allow seniors and those (405) 325-2278 with disabilities to sit, and remain seated on FAX (405) 325-7490 bus. • Pull signal cord one block ahead of stop; Office hours: 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday-Friday check for personal items before leaving. Buses operate: • Ask the operator for assistance, call 7 a.m. to 10 p.m. Monday-Friday 325-2278, or visit ridecart.com/howtoride 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Saturday for more information. (CARTaccess: See Page 15) rideCART.com CARTgps.com Transfers Follow @CARTNorman on Twitter Passengers must ask operator for a transfer Like CART on Facebook ticket when boarding the bus. Passengers will Download the App not receive a transfer when exiting the bus. The transfer is valid for one transfer within two hours. -

“Selective Memories” from 800 Chautauqua - Fall 1979-Spring 1985

“Selective Memories” from 800 Chautauqua - Fall 1979-Spring 1985 (... from Long-Haired Country Boy to Preppy, and Back Again, ...or, Sort Of) A Collaborative Effort among: Donald M. Lehman ’83, Rob F. M. Robertson ’84, and Many Other Good Brothers* *A special thanks to Wade L. McClure ’82 (current Dallas County Candidate for Garbage Inspector), for reminding us we all have “selective memories” of our otherwise memorable years at 800 Chautauqua, Norman, Oklahoma. The authors also express thanks to many other “veterans” of the Beta House in the early 1980’s who took their time to contribute their own selective memories - some of which, for various legal reasons, cannot go into print. _______________________________________ Preface: A Studious and Historical Perspective of the Early 1980’s at 800 Chautauqua: The proof is in the pictures. Or, more specifically, the proof is in the Chapter’s composites and Party-Pics. In retrospect, the period from Fall 1979 to Spring 1985 saw major changes in the picture of “Joe Beta” hanging over the mantle in the Dining Room at 800 Chautauqua, as well as the world in which Joe Beta enjoyed his college experience and planned for the future. In the late 1970’s “Joe Beta” had shoulder length hair and wore a jean jacket or a goose- down vest as a fashion statement. By the dawn of the 1980’s, except at “Barn Dance Time” and during ski trips, Joe was a relatively clean-cut guy appearing in our Chapter composite with a Polo or Gittman Brothers button-down shirt, donning a thin, neatly dimpled tie with regimental stripes, and he was probably wearing topsiders without socks. -

Consolidated Plan

City of Norman Community Development Block Grant and HOME Investment Partnerships Program Consolidated Plan 2020-2024 First Year Action Plan 2020 Department of Planning and Community Development Grants Division 2020-2024 Consolidated Plan First Year Action Plan Consolidated Plan CITY OF NORMAN Approved May 12, 2020 1 OMB Control No: 2506-0117 (exp. 06/30/2018) 2020-2024 Consolidated Plan First Year Action Plan CITY OF NORMAN 2020-2024 CONSOLIDATED PLAN 2020-2021 ACTION PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES-05 Executive Summary 4 THE PROCESS PR-05 Lead & Responsible Agencies 11 PR-10 Consultation 12 PR-15 Citizen Process 19 NEEDS ASSESSMENT NA-05 Overview 23 NA-10 Housing Needs Assessment 24 NA-15 Disproportionately Greater Need: Housing Problems 34 NA-20 Disproportionately Greater Need: Severe Housing Problems 39 NA-25 Disproportionately Greater Need: Housing Cost Burdens 43 NA-30 Disproportionately Greater Need: Discussion 44 NA-35 Public Housing 45 NA-40 Homeless Needs Assessment 51 NA-45 Non-Homeless Special Needs Assessment 57 NA-50 Non-Housing Community Development Needs 60 MARKET ANALYSIS MA-05 Overview 64 MA-10 Number of Housing Units 65 MA-15 Cost of Housing 68 MA-20 Condition of Housing 71 MA-25 Public and Assisted Housing 75 MA-30 Homeless Facilities 77 MA-35 Special Needs Facilities and Services 80 MA-40 Barriers to Affordable Housing 83 MA-45 Non-Housing Community Development Assets 84 MA-50 Needs and Market Analysis Discussion 90 MA-55 Broadband Needs 92 MA-60 Hazard Mitigation 93 Consolidated Plan CITY OF NORMAN Approved May 12, 2020 2 OMB Control No: 2506-0117 (exp. -

The University of Tulsa

The University of Tulsa Class of 1964 Memory Book The University of Tulsa Alma Mater Hail to thee Alma Mater, Gold and blue, Praise from thy sons and daughters, Old and new. Pride in our hearts, Our voices let us raise, Filled with devotion We will sing thy praise. Alma Mater, now we honor, Loyal, always true, We will lift our voice in chorus. Hail to Tulsa U! 1 9 6 4 Greetings From the President Dear Friends, This Homecoming we salute the members of the Class of 1964, who graduated in one of the iconic years of recent American history. From Beatlemania to the Ford Mustang to the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, your year brought sweeping changes to American culture and society. Of course, there were plenty of worries and woes, too – including tensions with the Soviets, escalating war in Vietnam, and ugly violence in the South. Those days delivered both turmoil and triumph in ample measure. As it was then, it remains our mission here at The University of Tulsa to prepare young men and women to meet the challenges and opportunities of their time. That process includes a broad grounding in the humanities and liberal arts, thorough instruction in a student’s chosen major, an emphasis on service to others, and the daily inspiration of being part of a distinguished university family. As an alumnus or alumna, you remain an important member of that family. Your example illustrates how a TU education helps to shape a lifetime of success, both in one’s career and in one’s community. -

Startnorman BETTER BLOCK

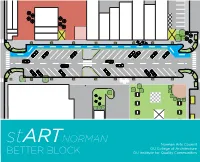

BETTER BLOCK st ART NORMAN 7 8 6 5 4 2 3 1 OU Institute for QualityCommunities for OU Institute OU College ofArchitecture OU College Norman Arts Council The University of Oklahoma College of Architecture Norman Arts Council Institute for Quality Communities MAINSITE Contemporary Art 830 Van Vleet Oval, Gould Hall, Room 165 122 E Main Street Norman, Oklahoma 73019 Norman, Oklahoma 73069 iqc.ou.edu www.normanarts.org contents Introduction Collaborators Analysis Traffic Volume Traffic Speed Site History Noise Walk and Bike One-Way Streets Better Block Plan Final Concept Construction Event Day Results Next Steps introduction The Norman Arts Council created StART Norman to demonstrate how art is playing a Tactical urbanism role in community revitalization, borrowing from two successful models. No Longer Empty is an organization in New York that creates a site- means lighter, specific art installation to temporarily occupy vacant spaces. The Better Block is a model quicker, cheaper originating in Dallas, Texas, that temporarily transforms streetscapes to better serve the needs interventions. of daily life. The University of Oklahoma Institute for Quality Communities (IQC) and Norman Arts Council hosted the creators of No Longer Empty and the Better Block for workshops walking volunteers Tactical urbanism is a term for a growing and students through how the programs work. movement of citizen-led ‘lighter, quicker, cheaper’ Manon Slome of No Longer Empty presented at interventions in the built environment, including Gould Hall in September, and Jason Roberts and Better Block. Tactical urbanism and other lighter, Andrew Howard of the Better Block presented at quicker, cheaper methods are increasingly MAINSITE Gallery in February. -

Norman Oklahoma 2008

NORMAN OKLAHOMA 2008 economic abstract population t a x e s transportation l a b o r i n c o m e h o u s i n g education business resources healthcare quality of life a r t s & entertainment p o p u l a t i o n t a x e s transportation l a b o r i n c o m e h o u s i n g e d u c a t i o n business resources h e a l t h c a r e quality of life arts & entertainment population t a x e s transportation l a b o r Norman, Oklahoma is a special place… With a rich history beginning in 1889, Norman is home to the state’s premier research university, the University of Oklahoma, and is a part of the dynamic Oklahoma City metropolitan area with over 1 million residents. Norman is a community that deeply cares for its citizens with programs like Food for Friends, The Center for Children and Families, Health For Friends, and the list goes on, all supported by our successful United Way programs. Norman Regional, a premier municipal hospital, is building a new campus offering the very best in healthcare. Our community offers job opportunities in a wide range of companies such as Astellas Pharma, Hitachi, Johnson Controls, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Sitel, OfficeMax, and Chickasaw Nation Industries. Norman is a diverse community with a rich history. We love calling Norman home, and I think you will too.