Hitler's Forgotten Genocides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reel-To-Real: Intimate Audio Epistolarity During the Vietnam War Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requireme

Reel-to-Real: Intimate Audio Epistolarity During the Vietnam War Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Alan Campbell, B.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Ryan T. Skinner, Advisor Danielle Fosler-Lussier Barry Shank 1 Copyrighted by Matthew Alan Campbell 2019 2 Abstract For members of the United States Armed Forces, communicating with one’s loved ones has taken many forms, employing every available medium from the telegraph to Twitter. My project examines one particular mode of exchange—“audio letters”—during one of the US military’s most trying and traumatic periods, the Vietnam War. By making possible the transmission of the embodied voice, experiential soundscapes, and personalized popular culture to zones generally restricted to purely written or typed correspondence, these recordings enabled forms of romantic, platonic, and familial intimacy beyond that of the written word. More specifically, I will examine the impact of war and its sustained separations on the creative and improvisational use of prosthetic culture, technologies that allow human beings to extend and manipulate aspects of their person beyond their own bodies. Reel-to-reel was part of a constellation of amateur recording technologies, including Super 8mm film, Polaroid photography, and the Kodak slide carousel, which, for the first time, allowed average Americans the ability to capture, reify, and share their life experiences in multiple modalities, resulting in the construction of a set of media-inflected subjectivities (at home) and intimate intersubjectivities developed across spatiotemporal divides. -

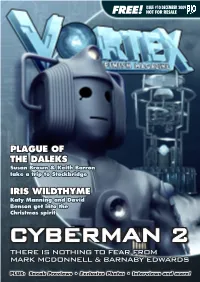

Plague of the Daleks Iris Wildthyme

ISSUE #10 DECEMBER 2009 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE PLAGUE OF THE DALEKS Susan Brown & Keith Barron take a trip to Stockbridge IRIS WILDTHYME Katy Manning and David Benson get into the Christmas spirit CYBERMAN 2 THERE IS NOTHING TO FEAR FROM MARK MCDONNELL & barnaby EDWARDS PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL THE BIG FINISH SALE Hello! This month’s editorial comes to you direct Now, this month, we have Sherlock Holmes: The from Chicago. I know it’s impossible to tell if that’s Death and Life, which has a really surreal quality true, but it is, honest! I’ve just got into my hotel to it. Conan Doyle actually comes to blows with Prices slashed from 1st December 2009 until 9th January 2010 room and before I’m dragged off to meet and his characters. Brilliant stuff by Holmes expert greet lovely fans at the Doctor Who convention and author David Stuart Davies. going on here (Chicago TARDIS, of course), I And as for Rob’s book... well, you may notice on thought I’d better write this. One of the main the back cover that we’ll be launching it to the public reasons we’re here is to promote our Sherlock at an open event on December 19th, at the Corner Holmes range and Rob Shearman’s book Love Store in London, near Covent Garden. The book will Songs for the Shy and Cynical. Have you bought be on sale and Rob will be signing and giving a either of those yet? Come on, there’s no excuse! couple of readings too. -

Download Book

0111001001101011 01THE00101010100 0111001001101001 010PSYHOLOGY0111 011100OF01011100 010010010011010 0110011SILION011 01VALLEY01101001 ETHICAL THREATS AND EMOTIONAL UNINTELLIGENCE 01001001001110IN THE TECH INDUSTRY 10 0100100100KATY COOK 110110 0110011011100011 The Psychology of Silicon Valley “As someone who has studied the impact of technology since the early 1980s I am appalled at how psychological principles are being used as part of the busi- ness model of many tech companies. More and more often I see behaviorism at work in attempting to lure brains to a site or app and to keep them coming back day after day. This book exposes these practices and offers readers a glimpse behind the “emotional scenes” as tech companies come out psychologically fir- ing at their consumers. Unless these practices are exposed and made public, tech companies will continue to shape our brains and not in a good way.” —Larry D. Rosen, Professor Emeritus of Psychology, author of 7 books including The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High Tech World “The Psychology of Silicon Valley is a remarkable story of an industry’s shift from idealism to narcissism and even sociopathy. But deep cracks are showing in the Valley’s mantra of ‘we know better than you.’ Katy Cook’s engaging read has a message that needs to be heard now.” —Richard Freed, author of Wired Child “A welcome journey through the mind of the world’s most influential industry at a time when understanding Silicon Valley’s motivations, myths, and ethics are vitally important.” —Scott Galloway, Professor of Marketing, NYU and author of The Algebra of Happiness and The Four Katy Cook The Psychology of Silicon Valley Ethical Threats and Emotional Unintelligence in the Tech Industry Katy Cook Centre for Technology Awareness London, UK ISBN 978-3-030-27363-7 ISBN 978-3-030-27364-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27364-4 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020 This book is an open access publication. -

Two New Studies Challenge Received Opinions About How the Soviet

First Films of the Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and the Genocide of the Jews, 1938–1946, Jeremy Hicks (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012), iii + 300 pp., pbk. $28.95. The Phantom Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and Jewish Catastrophe,Olga Gershenson (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2013), ii + 276 pp., pbk. $29.25, electronic version available. Two new studies challenge received opinions about how the Soviet Union represented the persecution and mass murder of the Jews before, during, and after the “Great Patriotic War.” Many standard histories of World War II and its aftermath in the USSR—Alexander Werth’s classic Russia at War (1964), Amir Weiner’s Making Sense of War (2001), and Yitzhak Arad’s recent The Holocaust in the Soviet Union (2009) are representative examples—underscore the ambivalence, indeed, the outright hos- tility, of Soviet authorities toward singling out Jews as the Nazis’ particular targets. Candid reports or allusions to the slaughter did appear initially in official pronounce- ments and major news outlets, but they soon became infrequent and increasingly vague; Jewish victims were routinely described only as “peaceful Soviet citizens,” their ethnic identities suppressed. Accounts of the Nazis’ killing of Jews were relegated to small-circulation Yiddish newspapers such as Einikayt, sponsored by the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. The reasons for this suppression of terrible truths were complex. The Communists were, ostensibly, ideologically opposed to differentiating among civilian victims of different national groups, even as they ranked these groups according to their alleged contributions to the defense against the German onslaught.1 Given the extent of civilian deaths, they also feared alienating other ethnic communities. -

Subject Listing of Numbered Documents in M1934, OSS WASHINGTON SECRET INTELLIGENCE/SPECIAL FUNDS RECORDS, 1942-46

Subject Listing of Numbered Documents in M1934, OSS WASHINGTON SECRET INTELLIGENCE/SPECIAL FUNDS RECORDS, 1942-46 Roll # Doc # Subject Date To From 1 0000001 German Cable Company, D.A.T. 4/12/1945 State Dept.; London, American Maritime Delegation, Horta American Embassy, OSS; (Azores), (McNiece) Washington, OSS 1 0000002 Walter Husman & Fabrica de Produtos Alimonticios, "Cabega 5/29/1945 State Dept.; OSS Rio de Janeiro, American Embassy Branca of Sao Paolo 1 0000003 Contraband Currency & Smuggling of Wrist Watches at 5/17/1945 Washington, OSS Tangier, American Mission Tangier 1 0000004 Shipment & Movement of order for watches & Chronographs 3/5/1945 Pierce S.A., Switzerland Buenos Aires, American Embassy from Switzerland to Argentine & collateral sales extended to (Manufactures) & OSS (Vogt) other venues/regions (Washington) 1 0000005 Brueghel artwork painting in Stockholm 5/12/1945 Stockholm, British Legation; London, American Embassy London, American Embassy & OSS 1 0000006 Investigation of Matisse painting in possession of Andre Martin 5/17/1945 State Dept.; Paris, British London, American Embassy of Zurich Embassy, London, OSS, Washington, Treasury 1 0000007 Rubens painting, "St. Rochus," located in Stockholm 5/16/1945 State Dept.; Stockholm, British London, American Embassy Legation; London, Roberts Commission 1 0000007a Matisse painting held in Zurich by Andre Martin 5/3/1945 State Dept.; Paris, British London, American Embassy Embassy 1 0000007b Interview with Andre Martiro on Matisse painting obtained by 5/3/1945 Paris, British Embassy London, American Embassy Max Stocklin in Paris (vice Germans allegedly) 1 0000008 Account at Banco Lisboa & Acores in name of Max & 4/5/1945 State Dept.; Treasury; Lisbon, London, American Embassy (Peterson) Marguerite British Embassy 1 0000008a Funds transfer to Regerts in Oporto 3/21/1945 Neutral Trade Dept. -

The 1958 Good Offices Mission and Its Implications for French-American Relations Under the Fourth Republic

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1970 The 1958 Good Offices Mission and Its Implications for French-American Relations Under the Fourth Republic Lorin James Anderson Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Anderson, Lorin James, "The 1958 Good Offices Mission and Its Implications forr F ench-American Relations Under the Fourth Republic" (1970). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1468. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.1467 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THBSIS Ol~ Lorin J'ames Anderson for the Master of Arts in History presented November 30, 1970. Title: The 1958 Good Offices Mission and its Implica tions for French-American Relations Under the Fourth Hepublic. APPROVED BY MEHllERS O~' THE THESIS CO.MNITTEE: Bernard Burke In both a general review of Franco-American re lations and in a more specific discussion of the Anglo American good offices mission to France in 1958, this thesis has attempted first, to analyze the foreign policies of France and the Uni.ted sta.tes which devel oped from the impact of the Second World Wa.r and, second, to describe Franco-American discord as primar ily a collision of foreign policy goals--or, even farther, as a basic collision in the national attitudes that shaped those goals--rather than as a result either of Communist harassment or of the clash of personalities. -

Not a Step Back by Leanne Crain

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo HOHONU 2016 Vol. 14 The beginning of the war in Russia came as a Not a Step Back surprise to the Soviet government, even though they Leanne Crain had been repeatedly warned by other countries that History 435 Nazi Germany was planning an attack on Russia, and nearly the entire first year of the German advance into Russia was met with disorganization and reactionary planning. Hitler, and indeed, most of the top military minds in Germany, had every right to feel confident in their troops. The Germans had swept across Europe, not meeting a single failure aside from the stubborn refusal of the British to cease any hostilities, and they had seen how the Soviets had failed spectacularly in their rushed invasion of Finland in the winter of 1939. The Germans had the utmost faith in their army and the success of their blitzkrieg strategy against their enemies further bolstered that faith as the Germans moved inexorably through the Ukraine and into Russian territory nearly uncontested. The Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact had kept Germany safe from any attack from Russia, “Such talk [of retreat] is lying and harmful, it weakens but Hitler had already planned for the eventuality of us and strengthens the enemy, because if there is no end invading Russia with Operation Barbarossa. Hitler was to the retreat, we will be left with no bread, no fuel, no convinced that the communist regime was on the verge metals, no raw materials, no enterprises, no factories, of collapse, and that the oppressed people under Stalin and no railways. -

How Will the Seventh Doctor Cope with a Companion Who Despises

ISSUE #12 FEBRUARY 2010 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE JACQUELINE RAYNER We chat to the writer of The Suffering DAVID GARFIELD chalks up another memorable Who villain in The Hollows of Time REBECCA’S WORLD is finally here! HOWSYLV’ WILL THES SEVEN NEMESISTH DOCTOR COPE WITH A COMPANION WHO DESPISES HIM? PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL It’s February and it productions and we feels like I’ve only just also read out listeners’ recovered from that week emails and comment of Big Finish podcasts we on them… mostly in a produced in December! constructive fashion. If What do you mean you want to take part, you didn’t hear them? you can email us on Naturally, we’ve already [email protected]. continued with our If you want to make an January podcast and the audio appearance in February one will be on the podcast, why not THE DOCTOR’S the way soon. send us an mp3 version So I thought it was with your email? I think NEW COMPANION high time I brought the that would be fun. IS ALSO HIS podcasts to the attention of SWORN ENEMY! any of you out there who The newest haven’t yet discovered feature, which we STARRING them. We put them up on started in December, the Big Finish site at least SYLVESTER MCCOY AS THE DOCTOR is the shameless once a month. They usually contain a chaotic mixture AND TRACEY CHILDS AS KLEIN phenomenon known as ‘the podcast competition’. of David Richardson, Paul Spragg, Alex Mallinson, In each podcast from now on, we will be giving me and possibly a guest star, talking about the latest away a prize! Now that’s what I call bribery! A THOUSAND TINY WINGS releases, tea and what we’re eating for lunch. -

Annual Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives Lecture

King's College London Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives Annual Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives Lecture How the cold war froze the history of World War Two Professor David Reynolds, FBA given Tuesday, 15 November 2005 © 2005 Copyright in all or part of this text rests with David Reynolds, FBA, and save by prior consent of Professor David Reynolds, no part of parts of this text shall be reproduced in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, now known or to be devised. ‘Anyone who delves deeply into the history of wars comes to realise that the difference between written history and historical truth is more marked in that field than in any other.’ Basil Liddell Hart struck this warning note at the beginning of a 1947 survey of historical literature about the Second World War. In fact, he felt that overall this writing was superior to the instant histories of the Great War a quarter-century or so earlier, mainly because ‘war correspondents were allowed more scope, and more inside information’ in 1939-45 than in 1914-18 and therefore presented a much less varnished portrait of warfare. Since their view was ‘better balanced’, he predicted ‘there is less likely to be such a violent swing from illusion to disillusion as took place in the decade after 1918.’ 1 Despite this generally positive assessment of the emerging historiography of the Second World War, Liddell Hart did note ‘some less favourable factors.’ Above all, he said, ‘there is no sign yet of any adequate contribution to history from the Russian side, which played so large a part’ in the struggle. -

Empirical Approaches to Military History

Karl-Heinz Frieser. The Blitzkrieg Legend: The 1940 Campaign in the West. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2005. xx + 507 pp. $47.50, cloth, ISBN 978-1-59114-294-2. Evan Mawdsley. Thunder in the East: The Nazi-Soviet War 1941-1945. London: Hodder, 2005. xxvi + 502 pp. $35.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-340-80808-5. Reviewed by James V. Koch Published on H-German (June, 2006) The world does not lack for military histories are written about in the historical surveys that of World War II, general or specific. Hence, when college students and others read. They appeal pri‐ new ones appear, it is legitimate to ask, do they marily to specialists who continue to dissect these really provide new information, insights or inter‐ campaigns, both of which are classics in the realm pretations? Both Frieser's look at the astonishing of conventional land warfare. six-week 1940 German campaign in the West that Frieser argues persuasively that Germany drove France out of the war and Mawdsley's ex‐ took several huge risks by attacking France, amination of the titanic 1941-45 German/Soviet Britain, Belgium and the Netherlands (the West‐ battle on the Eastern front meet that test. Both ern Allies) on May 10, 1940. Germany was unpre‐ provide new data, or at least bring together in one pared for anything more than a very short war book data that have been dispersed over many lo‐ and chose a strategy (thrusting through the sup‐ cations. Further, both authors look at these cam‐ posedly impenetrable Ardennes, crossing the paigns a bit differently than previous researchers Meuse, and driving to the Atlantic Coast) that and prod us to reformulate our understanding of could have been frustrated in a half-dozen ways critical aspects of these battles. -

Connecticut College Alumnae News, August 1954 Connecticut College

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Alumni News Archives 8-1954 Connecticut College Alumnae News, August 1954 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/alumnews Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "Connecticut College Alumnae News, August 1954" (1954). Alumni News. Paper 108. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/alumnews/108 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Archives at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni News by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Connecticut College Alumnae News Playing fields and Long Island Sound seen from Palmer Library, August, 1954 COLLEGE CALENDAR NOVEMBER 1954 - JUNE 1955 NOVEMBER FEBRUARY 7 Monday Second semester begins, 8 A.M. 24 Wednesday Thanksgiving recess begins, 11: lO A.M. 11 Friday Period for change of individual pro- Thanksgiving recess ends, 11 P.M. 28 Sunday grams ends, 4 P. M. APRIL DECEMBER 2 Saturday Spring recess begins, 11: 10 A.M. Spring recess ends, 11 P.M. 18 Saturday Christmas recess begins, 11: 10 A.M. 12 Tuesday MAY Period for election of courses for JANUARY 9-13 1955-56 4 Tuesday Christmas recess ends, 11 P.M. Friday Period ends, 4 P.M. Registration foe second semester 13 lO-14 Friday Comprehensive examinations for Period closes, 4 P,M. 27 14 Friday seniors Reading period 17-22 23-28 Reading period Review period 24~25 Monday Review period 26 Wednesday Mid-year examinations begin 30 31 Tuesday Final examinations begin FEBRUARY JUNE 3 Thursday Mid-year examinations end 8 Wednesday Final examinations end Commencement 6 Sunday Inter-semester recess ends, 11 P.M. -

Geoffrey Beevers Is the Master*

ISSUE 40 • JUNE 2012 NOT FOR RESALE FREE! GEOFFREY BEEVERS IS THE MASTER* PLUS! MARK STRICKSON & SARAH SUTTON Nyssa and Turlough Interviewed! I KNOW THAT VOICE... Famous names in Big Finish! *AND YOU WILL OBEY HIM! SNEAK PREVIEWS EDITORIAL AND WHISPERS e love stories. You’ll be hearing those words from us a lot more over the coming months. We’re only saying it because it’s the truth. And in THE FOURTH DOCTOR ADVENTURES a way, you’ve been hearing it from us since we started all this, right SERIES 3 W back in 1998, with Bernice Summerfield! Every now and then, I think it’s a good idea to stop and consider why we do 2014 might seem what we do; especially when, as has happened recently, we’ve been getting such a long way away, a pounding by a vociferous minority in online forums. As you may know, there but it’ll be here have been some teething problems with the changeover to our new website. before you know There was a problem with the data from the old site, relating to the downloads it – and so we’re in customers’ accounts. It seems that the information was not complete and had already in the some anomalous links in it, which meant that some downloads didn’t appear and studio recording others were allocated incorrectly. Yes, we accidentally gave a lot of stuff away! And, the third series of in these cash-strapped times, that was particularly painful for us. Thanks to all of Fourth Doctor Adventures, once again you who contacted us to say you wouldn’t take advantage of these – shall we say featuring the Doctor and Leela.