Protest in America Teaching Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday Calendar 20142018

THURSDAY Five-Year Calendar Unit 2014 20152016 2017 2018 Week # 1 Jan. 2 - Jan. 9 Jan. 1 - Jan. 8 Jan. 7 - Jan. 14 Jan. 5 - Jan. 12 Jan. 4 - Jan. 11 2 Jan. 9 - Jan. 16 Jan. 8 - Jan. 15 Jan. 14 - Jan. 21 Jan. 12 - Jan. 19 Jan. 11 - Jan. 18 3 Jan. 16 - Jan. 23 Jan. 15 - Jan. 22 Jan. 21 - Jan 28 Jan. 19 - Jan. 26 Jan. 18 - Jan. 25 4 Jan. 23 - Jan. 30 Jan. 22 - Jan. 29 Jan. 28 - Feb. 4 Jan. 26 - Feb. 2 Jan. 25 - Feb. 1 5 Jan. 30 - Feb. 6 Jan. 29 - Feb. 5 Feb. 4 - Feb. 11 Feb. 2- Feb. 9 Feb. 1 - Feb. 8 6 Feb. 6 - Feb. 13 Feb. 5 - Feb. 12 Feb. 11 - Feb. 18 Feb. 9 - Feb. 16 Feb. 8 - Feb. 15 7 Feb. 13 - Feb. 20 Feb. 12 - Feb. 19 Feb. 18 - Feb. 25 Feb. 16 - Feb. 23 Feb. 15 - Feb. 22 8 Feb. 20 - Feb. 27 Feb. 19 - Feb. 26 Feb. 25 - Mar. 3 Feb. 23 - Mar. 2 Feb. 22 - Mar. 1 9 Feb. 27 - Mar. 6 Feb. 26 - Mar. 5 Mar. 3 - Mar. 10 Mar. 2 - Mar. 9 Mar. 1 - Mar. 8 10 Mar. 6 - Mar. 13 Mar. 5 - Mar. 12 Mar. 10 - Mar. 17 Mar. 9 - Mar. 16 Mar. 5 - Mar. 15 11 Mar. 13 - Mar. 20 Mar. 12 - Mar. 19 Mar. 17 - Mar. 24 Mar. 16 - Mar. 23 Mar. 15 - Mar. 22 12 Mar. 20 - Mar. 27 Mar. 19 - Mar. 26 Mar. 24 - Mar. 31 Mar. 23 - Mar. 30 Mar. 22 - Mar. -

2020-2021 Academic Year Grid ALL 11X17

Fall 2020 Spring 2021 Summer 2021* EVENTS / DEADLINES Session 1 Session 1 Session 2 Session 3 Session 4 Session 5 Session 6 Winter Mini Session 2 Session 3 Session 4 Session 5 Session 6 Summer Mini Session 1 Session 2 Session 3 Session 4 Regular Regular First Day of Classes September 28, October 19, November 2, December 21, February 22, *Please also see notes below August 24, 2020 August 24, 2020 August 24, 2020 January 19, 2021 January 19, 2021 January 19, 2021 March 22, 2021 April 5, 2021 May 17, 2021 June 7, 2021 June 7, 2021 June 7, 2021 July 12, 2021 2020 2020 2020 2020 2021 regarding college-specific dates and Monday Monday Monday Tuesday Tuesday Tuesday Monday Monday Monday Monday Monday Monday Monday Monday Monday Monday Monday Monday summer sessions meeting days. Labor Day Holiday (Fall); September 7, 2020 January 18, 2021 May 31, 2021 Martin Luther King Holiday (Spring); Monday Monday Monday Memorial Day (Summer) **Extended** September 30, October 21, November 4, December 22, February 24, Last Day to Add a Class September 1, August 26, 2020 August 26, 2020 January 26, 2021 January 21, 2021 January 21, 2021 March 24, 2021 April 7, 2021 May 18, 2021 June 8, 2021 June 8, 2021 June 8, 2021 July 13, 2021 2020 2020 2020 2020 2021 or be enrolled from the Wait List 2020 Wednesday Wednesday Tuesday Thursday Thursday Wednesday Wednesday Tuesday Tuesday Tuesday Tuesday Tuesday Wednesday Wednesday Wednesday Tuesday Wednesday Tuesday ORD - Official Reporting Day Last day to drop a course or withdraw without receiving a grade Last day to -

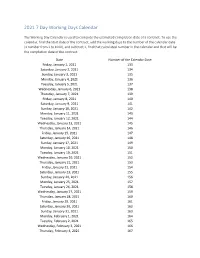

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

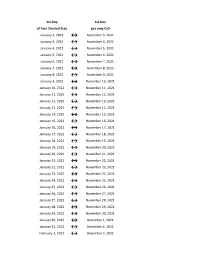

Flex Dates.Xlsx

1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call January 2, 2022 ↔ November 3, 2021 January 3, 2022 ↔ November 4, 2021 January 4, 2022 ↔ November 5, 2021 January 5, 2022 ↔ November 6, 2021 January 6, 2022 ↔ November 7, 2021 January 7, 2022 ↔ November 8, 2021 January 8, 2022 ↔ November 9, 2021 January 9, 2022 ↔ November 10, 2021 January 10, 2022 ↔ November 11, 2021 January 11, 2022 ↔ November 12, 2021 January 12, 2022 ↔ November 13, 2021 January 13, 2022 ↔ November 14, 2021 January 14, 2022 ↔ November 15, 2021 January 15, 2022 ↔ November 16, 2021 January 16, 2022 ↔ November 17, 2021 January 17, 2022 ↔ November 18, 2021 January 18, 2022 ↔ November 19, 2021 January 19, 2022 ↔ November 20, 2021 January 20, 2022 ↔ November 21, 2021 January 21, 2022 ↔ November 22, 2021 January 22, 2022 ↔ November 23, 2021 January 23, 2022 ↔ November 24, 2021 January 24, 2022 ↔ November 25, 2021 January 25, 2022 ↔ November 26, 2021 January 26, 2022 ↔ November 27, 2021 January 27, 2022 ↔ November 28, 2021 January 28, 2022 ↔ November 29, 2021 January 29, 2022 ↔ November 30, 2021 January 30, 2022 ↔ December 1, 2021 January 31, 2022 ↔ December 2, 2021 February 1, 2022 ↔ December 3, 2021 1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call February 2, 2022 ↔ December 4, 2021 February 3, 2022 ↔ December 5, 2021 February 4, 2022 ↔ December 6, 2021 February 5, 2022 ↔ December 7, 2021 February 6, 2022 ↔ December 8, 2021 February 7, 2022 ↔ December 9, 2021 February 8, 2022 ↔ December 10, 2021 February 9, 2022 ↔ December 11, 2021 February 10, 2022 ↔ December 12, 2021 February -

2019-2022 Calendar of Major Jewish Holidays

2019-2022 CALENDAR OF MAJOR JEWISH HOLIDAYS Please note: Jewish students may not be able to participate in school activities that take place on the days marked with an *. 2019 2020 2021 2022 PURIM Celebrates the defeat of the plot to destroy March 21 March 10 February 26 March 17 the Jews of Persia. PASSOVER Deliverance of the Jewish people from Egypt. The first *Eve. of April 19 *Eve. of April 8 *Eve. of March 27 *Eve of April 15 and last two days are observed as full holidays. There are *April 20 *April 9 *March 28 *April 16 dietary restrictions against leavened products (such as *April 21 *April 10 *March 29 *April17 bread, pastries, pasta, certain legumes and more) during *April 26 *April 15 *April 3 *April 21 all eight days of the holiday. *April 27 *April 16 *April 4 *April 22 SHAVUOT *Eve. of June 8 *Eve. of May 28 *Eve. of May 16 *Eve of June 3 Feast of Weeks, marks the giving of the Law (Torah) *June 9 *May 29 *May 17 *June 4 at Mt. Sinai. (Often linked with the Confirmation *June 10 *May 30 *May 18 *June 5 of teenagers.) ROSH HASHANAH *Eve. of Sept. 29 *Eve. of Sept. 18 *Eve. of Sept. 6 *Eve of Sept 25 The Jewish New Year; start of the Ten Days of Penitence. *Sept. 30 *Sept. 19 *Sept. 7 *Sept. 26 The first two days are observed as full holidays. *Oct. 1 *Sept. 20 *Sept. 8 *Sept. 27 YOM KIPPUR Day of Atonement; the most solemn day *Eve. -

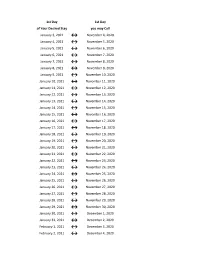

Flex Dates.Xlsx

1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call January 3, 2021 ↔ November 4, 2020 January 4, 2021 ↔ November 5, 2020 January 5, 2021 ↔ November 6, 2020 January 6, 2021 ↔ November 7, 2020 January 7, 2021 ↔ November 8, 2020 January 8, 2021 ↔ November 9, 2020 January 9, 2021 ↔ November 10, 2020 January 10, 2021 ↔ November 11, 2020 January 11, 2021 ↔ November 12, 2020 January 12, 2021 ↔ November 13, 2020 January 13, 2021 ↔ November 14, 2020 January 14, 2021 ↔ November 15, 2020 January 15, 2021 ↔ November 16, 2020 January 16, 2021 ↔ November 17, 2020 January 17, 2021 ↔ November 18, 2020 January 18, 2021 ↔ November 19, 2020 January 19, 2021 ↔ November 20, 2020 January 20, 2021 ↔ November 21, 2020 January 21, 2021 ↔ November 22, 2020 January 22, 2021 ↔ November 23, 2020 January 23, 2021 ↔ November 24, 2020 January 24, 2021 ↔ November 25, 2020 January 25, 2021 ↔ November 26, 2020 January 26, 2021 ↔ November 27, 2020 January 27, 2021 ↔ November 28, 2020 January 28, 2021 ↔ November 29, 2020 January 29, 2021 ↔ November 30, 2020 January 30, 2021 ↔ December 1, 2020 January 31, 2021 ↔ December 2, 2020 February 1, 2021 ↔ December 3, 2020 February 2, 2021 ↔ December 4, 2020 1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call February 3, 2021 ↔ December 5, 2020 February 4, 2021 ↔ December 6, 2020 February 5, 2021 ↔ December 7, 2020 February 6, 2021 ↔ December 8, 2020 February 7, 2021 ↔ December 9, 2020 February 8, 2021 ↔ December 10, 2020 February 9, 2021 ↔ December 11, 2020 February 10, 2021 ↔ December 12, 2020 February 11, 2021 ↔ December 13, 2020 -

Pay Week Begin: Saturdays Pay Week End: Fridays Check Date

Pay Week Begin: Pay Week End: Due to UCP no later Check Date: Saturdays Fridays than Monday 7:30am week 1 December 10, 2016 December 16, 2016 December 19, 2016 December 30, 2016 week 2 December 17, 2016 December 23, 2016 December 26, 2016 week 1 December 24, 2016 December 30, 2016 January 2, 2017 January 13, 2017 week 2 December 31, 2016 January 6, 2017 January 9, 2017 week 1 January 7, 2017 January 13, 2017 January 16, 2017 January 27, 2017 week 2 January 14, 2017 January 20, 2017 January 23, 2017 January 21, 2017 January 27, 2017 week 1 January 30, 2017 February 10, 2017 week 2 January 28, 2017 February 3, 2017 February 6, 2017 week 1 February 4, 2017 February 10, 2017 February 13, 2017 February 24, 2017 week 2 February 11, 2017 February 17, 2017 February 20, 2017 March 3, 2017 week 1 February 18, 2017 February 24, 2017 February 27, 2017 ***1 Week Pay Period Transition*** week 1 February 25, 2017 March 3, 2017 March 6, 2017 March 17, 2017 week 2 March 4, 2017 March 10, 2017 March 13, 2017 week 1 March 11, 2017 March 17, 2017 March 20, 2017 March 31, 2017 week 2 March 18, 2017 March 24, 2017 March 27, 2017 week 1 March 25, 2017 March 31, 2017 April 3, 2017 April 14, 2017 week 2 April 1, 2017 April 7, 2017 April 10, 2017 week 1 April 8, 2017 April 14, 2017 April 17, 2017 April 28, 2017 week 2 April 15, 2017 April 21, 2017 April 24, 2017 week 1 April 22, 2017 April 28, 2017 May 1, 2017 May 12, 2017 week 2 April 29, 2017 May 5, 2017 May 8, 2017 week 1 May 6, 2017 May 12, 2017 May 15, 2017 May 26, 2017 week 2 May 13, 2017 May 19, 2017 May -

June 5 Flooding News Release

CONTACT: Selina Tisdale, City of Midland Public Information Officer Bridgette Gransden, County of Midland Public Information Officer PHONE: 224-434-9073 DATE: June 5, 2020, 3 p.m. Midland County Flooding Updates – June 5, 3 p.m. New Phone Number for American Red Cross Long-Term Shelter Needs Residents who are still displaced from their homes and have long-term sheltering needs should be advised that a new phone number is available to call for assistance. The new phone number for the American Red Cross is 1-800-733-2767 (1-800-RED-CROS). Please select the following prompts: • Please press “4” for a disaster related need; • Then press “1” for assistance related to the spring flooding of 2020; • Then press “1” again for assistance related to the spring flooding of 2020; and • Press “3” if you are calling for the first time and do not have a case number Update on Test Results from COVID-19 Mass Testing Site From the Midland County Department of Public Health: Due to factors out of our control, the laboratory results from the COVID-19 testing clinic held at Dow Diamond May 30 – 31 are not expected to be available until Monday, June 8 at the earliest. The Midland County Department of Public Health has been in contact with the testing lab daily and will do everything in its power to get the results out quickly. Final Sunday Hours at Midland Landfill; City Flood Debris Collection Deadline The Midland Sanitary Landfill will hold its final Sunday hours this Sunday, June 7, from 8 a.m. -

Caltrans Construction 5-Workday Calendar 2028

CONSTRUCTION 5-WORKDAY CALENDAR Year 2028 JANUARY JULY Sund Mond Tuesd Wedn Thurs Friday Satur Sund Mond Tuesd Wedn Thurs Friday Satur 1 1 678 679 680 681 682 804 805 806 807 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 683 684 685 686 687 808 809 810 811 812 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 688 689 690 691 813 814 815 816 817 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 692 693 694 695 696 818 819 820 821 822 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 697 823 30 31 30 31 FEBRUARY AUGUST Sund Mond Tuesd Wedn Thurs Friday Satur Sund Mond Tuesd Wedn Thurs Friday Satur 698 699 700 701 824 825 826 827 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 702 703 704 705 706 828 829 830 831 832 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 707 708 709 710 711 833 834 835 836 837 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 712 713 714 715 838 839 840 841 842 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 716 717 843 844 845 846 27 28 29 27 28 29 30 31 MARCH SEPTEMBER Sund Mond Tuesd Wedn Thurs Friday Satur Sund Mond Tuesd Wedn Thurs Friday Satur 718 719 720 847 1 2 3 4 1 2 721 722 723 724 725 848 849 850 851 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 726 727 728 729 730 852 853 854 855 856 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 731 732 733 734 735 857 858 859 860 861 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 736 737 738 739 862 863 864 865 866 26 27 28 29 30 31 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 APRIL OCTOBER Sund Mond Tuesd Wedn Thurs Friday Satur Sund Mond Tuesd Wedn Thurs Friday Satur 867 868 869 870 871 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 740 741 742 743 744 872 873 874 875 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 745 746 747 748 749 876 877 878 879 880 -

Date of Close Contact Exposure

Date of Close Contact Exposure 7 days 10 days 14 days Monday, November 16, 2020 Tuesday, November 24, 2020 Friday, November 27, 2020 Tuesday, December 1, 2020 Tuesday, November 17, 2020 Wednesday, November 25, 2020 Saturday, November 28, 2020 Wednesday, December 2, 2020 Wednesday, November 18, 2020 Thursday, November 26, 2020 Sunday, November 29, 2020 Thursday, December 3, 2020 Thursday, November 19, 2020 Friday, November 27, 2020 Monday, November 30, 2020 Friday, December 4, 2020 Friday, November 20, 2020 Saturday, November 28, 2020 Tuesday, December 1, 2020 Saturday, December 5, 2020 Saturday, November 21, 2020 Sunday, November 29, 2020 Wednesday, December 2, 2020 Sunday, December 6, 2020 Sunday, November 22, 2020 Monday, November 30, 2020 Thursday, December 3, 2020 Monday, December 7, 2020 Monday, November 23, 2020 Tuesday, December 1, 2020 Friday, December 4, 2020 Tuesday, December 8, 2020 Tuesday, November 24, 2020 Wednesday, December 2, 2020 Saturday, December 5, 2020 Wednesday, December 9, 2020 Wednesday, November 25, 2020 Thursday, December 3, 2020 Sunday, December 6, 2020 Thursday, December 10, 2020 Thursday, November 26, 2020 Friday, December 4, 2020 Monday, December 7, 2020 Friday, December 11, 2020 Friday, November 27, 2020 Saturday, December 5, 2020 Tuesday, December 8, 2020 Saturday, December 12, 2020 Saturday, November 28, 2020 Sunday, December 6, 2020 Wednesday, December 9, 2020 Sunday, December 13, 2020 Sunday, November 29, 2020 Monday, December 7, 2020 Thursday, December 10, 2020 Monday, December 14, 2020 Monday, November -

Friday Five-Year Vacation Calendar (Units #1301 Through #2402)

On Kangaroo Lake Friday Five-Year Vacation Calendar (units #1301 through #2402) Unit Week 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Number 1 Jan. 7 - Jan. 14 Jan. 6 - Jan. 13 Jan. 4 - Jan. 11 Jan. 3 - Jan. 10 Jan. 2 - Jan. 9 2 Jan. 14 - Jan. 21 Jan. 13 - Jan. 20 Jan. 11 - Jan. 18 Jan. 10 - Jan. 17 Jan. 9 - Jan. 16 3 Jan. 21 - Jan. 28 Jan. 20 - Jan. 27 Jan. 18 - Jan. 25 Jan. 17 - Jan. 24 Jan. 16 - Jan. 23 4 Jan. 28 - Feb. 4 Jan. 27 - Feb. 3 Jan. 25 - Feb. 1 Jan. 24 - Jan. 31 Jan. 23 - Jan. 30 5 Feb. 4 - Feb. 11 Feb. 3 - Feb. 10 Feb. 1 - Feb. 8 Jan. 31 - Feb. 7 Jan. 30 - Feb. 6 6 Feb. 11 - Feb. 18 Feb. 10 - Feb. 17 Feb. 8 - Feb. 15 Feb. 7 - Feb. 14 Feb. 6 - Feb. 13 7 Feb. 18 - Feb. 25 Feb. 17 - Feb. 24 Feb. 15 - Feb. 22 Feb. 14 - Feb. 21 Feb. 13 - Feb. 20 8 Feb. 25 - Mar. 4 Feb. 24 - Mar. 2 Feb. 22 - Mar. 1 Feb. 21 - Feb. 28 Feb. 20 - Feb. 27 9 Mar. 4 - Mar. 11 Mar. 2 - Mar. 9 Mar. 1 - Mar. 8 Feb. 28 - Mar. 7 Feb. 27 - Mar. 6 10 Mar. 11 - Mar. 18 Mar. 9 - Mar. 16 Mar. 8 - Mar. 15 Mar. 7 - Mar. 14 Mar. 6 - Mar. 13 11 Mar. 18 - Mar. 25 Mar. 16 - Mar. 23 Mar. 15 - Mar. 22 Mar. 14 - Mar. 21 Mar. 13 - Mar. 20 12 Mar. 25 - Apr. 1 Mar. 23 - Mar. 30 Mar. -

June 5, 2020 COVID-19 Status Report Oak Park Village Board of Trustees To: Village President and Village Board of Trustees

June 5, 2020 COVID-19 Status Report Oak Park Village Board of Trustees To: Village President and Village Board of Trustees Fr: Cara Pavlicek, Village Manager The memo is a means to share a brief summary of information regarding Village of Oak Park operational activities in response to COVID-19. In most cases, formal public guidance or employee guidance has been publicly disseminated via the Village website or Village social media channels. New Public Health Guidance Today, the Village of Oak Park Department of Public Health received notification of the following new COVID-19 cases: 2 Oak Park Residents whose ages range from 50s – 70s. Excluding individuals for which street addresses are not yet determined, the State of Illinois reports a total of two-hundred and ninety-six (296) total Oak Park COVID-19 cases. It is important to note that as patient tracking and case follow-up occurs, individuals listed within the number of Oak Park cases reported may change depending on residency confirmation. Also, Oak Park Public Health Director Mike Charley reported today the twenty-first death of Oak Park residents believed to be related to the COVID-19 coronavirus. The fatality was a male in his 70s. The resident had earlier tested positive for the virus, but the final cause of death will be determined by the Cook County Medical Examiner. Director Charley expressed his sincere condolences to the resident’s friends and family for the loss of their loved one. The Oak Park Department of Public Health is notified of positive tests as established by state and local public health protocol.