Unit 30 Soclal Significance Pilgrimages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hajj and the Malayan Experience, 1860S–1941

KEMANUSIAAN Vol. 21, No. 2, (2014), 79–98 Hajj and the Malayan Experience, 1860s–1941 AIZA MASLAN @ BAHARUDIN Universiti Sains Malaysia, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia [email protected] Abstract. Contrary to popular belief, the hajj is a high-risk undertaking for both pilgrims and administrators. For the Malay states, the most vexing problem for people from the mid-nineteenth century until the Second World War was the spread of epidemics that resulted from passenger overcrowding on pilgrim ships. This had been a major issue in Europe since the 1860s, when the international community associated the hajj with the outbreak and spread of infectious diseases. Accusations were directed at various parties, including the colonial administration in the Straits Settlements and the British administration in the Malay states. This article focuses on epidemics and overcrowding on pilgrim ships and the resultant pressure on the British, who were concerned that the issue could pose a threat to their political position, especially when the Muslim community in the Malay states had become increasingly exposed to reformist ideas from the Middle East following the First World War. Keywords and phrases: Malays, hajj, epidemics, British administration, Straits Settlements, Malay states Introduction As with health and education, the colonial powers had to handle religion with great care. The colonisers covertly used these three aspects not only to gain the hearts of the colonised but, more importantly, to maintain their reputation among other colonial powers. Roy MacLeod, for example, sees the introduction of Western medicine to colonised countries as functioning as both cultural agency and western expansion (MacLeod and Lewis 1988; Chee 1982). -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Pilgrimage Places and Sacred Geometries

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Geography Faculty Publications Geography Program (SNR) 2009 Pilgrimage Places and Sacred Geometries Robert Stoddard University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geographyfacpub Part of the Geography Commons Stoddard, Robert, "Pilgrimage Places and Sacred Geometries" (2009). Geography Faculty Publications. 4. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geographyfacpub/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Geography Program (SNR) at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Geography Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in PILGRIMAGE: SACRED LANDSCAPES AND SELF-ORGANIZED COMPLEXITY, edited by John McKim Malville & Baidyanath Saraswati, with a foreword by R. K. Bhattacharya (New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, 2009), pp. 163-177. Copyright 2009 Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. 1~ Pilgrimage Places and Sacred Geometries Robert H. Stoddard PILGRIMAGE flows, often involving millions of people, attract the attention of scholars seeking to explain these patterns of movement. A multitude of explanations have been attempted, but none has provided an entirely satisfactory understanding about why certain sites attract worshippers to undertake the sacrifices of pilgrimage. It is recognized that, from the perspective of many religious traditions, Earth space is not homogeneous - that specific places are sacred and different from the surrounding profane land. The reasons certain locations are holy and attract pilgrims from afar have long evoked the geographic question: Why are pilgrimage places distributed as they are? The potential answers discussed here focus on general principles of location - rather than on ideographic descriptions of particular pilgrimage places. -

The Impact of Pilgrimage Upon the Faith and Faith-Based Practice of Catholic Educators

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2018 The impact of pilgrimage upon the faith and faith-based practice of Catholic educators Rachel Capets The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Capets, R. (2018). The impact of pilgrimage upon the faith and faith-based practice of Catholic educators (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Education)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/219 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF PILGRIMAGE UPON THE FAITH AND FAITH-BASED PRACTICE OF CATHOLIC EDUCATORS A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy, Education The University of Notre Dame, Australia Sister Mary Rachel Capets, O.P. 23 August 2018 THE IMPACT OF PILGRIMAGE UPON THE CATHOLIC EDUCATOR Declaration of Authorship I, Sister Mary Rachel Capets, O.P., declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Education, University of Notre Dame Australia, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. -

Nehru's 'Discovery of India' the Role of Science in India's Development

NEHRU’S ‘THE DISCOVERY OF INDIA’ 157 Nehru’s ‘Discovery of India’ The Role of Science in India’s Development Science should unite and not break-up India ‘I love India, not because I have had the chance to be born on its soil but because she has saved through limitless ages the living words that have issued from the illuminated consciousness of her great sons’. So wrote our great poet Rabindranath Tagore several years ago but few among the modern generation of intelligent youth have bothered to get even a glimpse of what that glorious heritage of India was. Valmiki, Vyasa, Kalidasa and Bhavabhuthi are just names. The masses of India, however, are better informed, Rama¯yana and Maha¯bharatha have impressed on their mind the oneness of India. Every village, at least till recently, had a Bhajan Mandal where the entire village would participate. Pilgrimages were undertaken with great religious fervour to holy places like Varanasi, Gaya, Rameswaram, Dwarka, Puri and Haridwar, Badrinath and Amarnath. These inculcated in the minds of the people the vastness and variety of their homeland and welded them as one human entity. This tradition of unity and integrity of the country is being destroyed by the self-serving politicians jockeying for power and sowing seeds of hatred in an otherwise peaceful population. Science has barely tried to perpetuate this unifying influence. ‘The Discovery of India’ by Nehru When my mind was deeply distressed at the present state of the country, I was drawn to a review of the book ‘The Discovery of India’, a recent edition of which has been brought out by the Penguin publishers. -

Lord Buddha in the Cult of Lord Jagannath

June - 2014 Odisha Review Lord Buddha in the Cult of Lord Jagannath Abhimanyu Dash he Buddhist origin of Lord Jagannath was (4) At present an image of Buddha at Ellora Tfirst propounded by General A. Cunningham is called Jagannath which proves Jagannath and which was later on followed by a number of Buddha are identical. scholars like W.W.Hunter, W.J.Wilkins, (5) The Buddhist celebration of the Car R.L.Mitra, H.K. Mahatab, M. Mansingh, N. K. Festival which had its origin at Khotan is similar Sahu etc. Since Buddhism was a predominant with the famous Car Festival of the Jagannath cult. religion of Odisha from the time of Asoka after (6) Indrabhuti in his ‘Jnana Siddhi’ has the Kalinga War, it had its impact on the life, referred to Buddha as Jagannath. religion and literature of Odisha. Scholars have (7) There are similar traditions in Buddhism made attempt to show the similarity of Jagannath as well as in the Jagannath cult. Buddhism was cult with Buddhism on the basis of literary and first to discard caste distinctions. So also there is archaeological sources. They have put forth the no caste distinction in the Jagannath temple at the following arguments to justify the Buddhist origin time of taking Mahaprasad. This has come from of Lord Jagannath. the Buddhist tradition. (1) In their opinion the worship of three (8) On the basis of the legend mentioned in symbols of Buddhism, Tri-Ratna such as the the ‘Dathavamsa’ of Dharmakirtti of Singhala, Buddha, the Dhamma (Dharma) and the Sangha scholars say that a tooth of Buddha is kept in the body of Jagannath. -

My Forays Into the World of the Tablä†

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2014 My Forays into the World of the Tablā Madeline Longacre SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Longacre, Madeline, "My Forays into the World of the Tablā" (2014). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1814. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1814 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MY FORAYS INTO THE WORLD OF THE TABL Ā Madeline Longacre Dr. M. N. Storm Maria Stallone, Director, IES Abroad Delhi SIT: Study Abroad India National Identity and the Arts Program, New Delhi Spring 2014 TABL Ā OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ………………………………………………………………………………………....3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ……………………………………………………………………………..4 DEDICATION . ………………………………………………………………………………...….....5 INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………………………….....6 WHAT MAKES A TABL Ā……………………………………………………………………………7 HOW TO PLAY THE TABL Ā…………………………………………………………………………9 ONE CITY , THREE NAMES ………………………………………………………………………...11 A HISTORY OF VARANASI ………………………………………………………………………...12 VARANASI AS A MUSICAL CENTER ……………………………………………………………….14 THE ORIGINS OF THE TABL Ā……………………………………………………………………...15 -

Tirupati City with Many Slums ; an Ill Health Environment to the Piligirim Centre” in Martin J

Krishnaiah, Dr. K. “Tirupati City With Many Slums ; An Ill Health Environment To The Piligirim Centre” in Martin J. Bunch, V. Madha Suresh and T. Vasantha Kumaran, eds., Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Environment and Health, Chennai, India, 15-17 December, 2003. Chennai: Department of Geography, University of Madras and Faculty of Environmental Studies, York University. Pages 226 – 232. TIRUPATI CITY WITH MANY SLUMS ; AN ILL HEALTH ENVIRONMENT TO THE PILIGIRIM CENTRE Dr. K. Krishnaiah Associate Professor, Department of Geography, S.V.University, Tirupati- 517 502 Abstract Industrialisation results in increasing urbanization. The accumulation of wealth and availability of more economic and job opportunities in the urban centres have resulted in the concentration of the population in the congested metropolitan areas and thus the formation and growth of big slum areas. These slum centres, when combined with industrial sectors, become more hazardous from the stand point of environmental degradation and pollution. If these slum centres are many, it is hazardous and causes ill health to the city like Tirupati, an important piligrim centre in the country. In the present study the emphasis was on the ratio of the total number of slums. 42 were identified in the small area 0.715 sq. km as per 2001 census in Tirupati. The author makes a caution that the higher the density of slums in the pilgrim centre, the more will be the ill health environment in terms of spread of diseases. Introduction The phenomenon of rapid urbanization in conjunction with industrialization has resulted in the growth of slums. The sprouting of slums occur due to many factors, such as the shortage of developed land for housing, the high prices of land beyond the reach of urban poor, and a large influx of rural migrants to the cities in search of jobs etc. -

Sacred Space on Earth : (Spaces Built by Societal Facts)

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 4 Issue 8 || August. 2015 || PP.31-35 Sacred Space On Earth : (Spaces Built By Societal Facts) Dr Jhikmik Kar Rani Dhanya Kumari College, Jiaganj, Murshidabad. Kalyani University. ABSTRACT: To the Hindus the whole world is sacred as it is believed to spring from the very body of God. Hindus call these sacred spaces to be “tirthas” which is the doorway between heaven and earth. These tirthas(sacred spaces) highlights the great act of gods and goddesses as well as encompasses the mythic events surrounding them. It signifies a living sacred geographical space, a place where everything is blessed pure and auspicious. One of such sacred crossings is Shrikshetra Purosottam Shetra or Puri in Orissa.(one of the four abodes of lord Vishnu in the east). This avenue collects a vast array of numerous mythic events related to Lord Jagannatha, which over the centuries attracted numerous pilgrims from different corners of the world and stand in a place empowered by the whole of India’s sacred geography. This sacred tirtha created a sacred ceremonial/circumbulatory path with the main temple in the core and the secondary shrines on the periphery. The mythical/ritual traditions are explained by redefining separate ritual (sacred) spaces. The present study is an attempt to understand their various features of these ritual spaces and their manifestations in reality at modern Puri, a temple town in Orissa, Eastern India. KEYWORDS: sacred geography, space, Jagannatha Temple I. Introduction Puri is one of the most important and famous sacred spaces (TirthaKhetra) of the Hindus. -

October 2021 Holy Land Pilgrimage

Join Father Ebuka Mbanude with Holy Redeemer Catholic Church Holy Land Pilgrimage October 13-22, 2021 For more information or to make a reservation contact: Nicole Lovell - NML Travel 208-953-1183 •[email protected] Oct. 18 - The Galilee MESSAGE FROM YOUR HOST Enjoy beautiful Capernaum, the center of Jesus’ ministry, and visit the synagogue located on the site where Jesus taught (Matt. 4:13, 23). Father Ebuka Mbanude Sail across the Sea of Galilee, reflecting on the gospel stories of Jesus Come and experience the land in which ‘the calming the storm. Listen to Jesus’ words from His Sermon on the Mount Word became flesh and dwelt among us’. at the Mount of Beatitudes (Matt. 5-7) and celebrate Mass at the Church Come and walk the path that Jesus, Mary of the Beatitudes. At Tabgha, traditional location of the feeding of the and the apostles walked; see the place of the 5,000, explore the Church of the Fish and the Loaves (Luke 9:10-17). Passion, death and burial of Jesus. Let the Take a moment to reflect and pray in the Chapel of the Primacy, where scriptures come alive for you as you understand the history of Peter professed his devotion to the risen Christ (John 21). In Magdala, the Holy Land, and deepen your relationship with God as you once home to Mary Magdalene, visit a recently discovered first-century pray in many holy places. Expect miracles; you will never be synagogue. Overnight in Tiberias. (B,D) the same. Oct. 19 - Mount Tabor, Mount Carmel & Emmaus As you stand on Mount Tabor, contemplate what it must have been like Father Ebuka Mbanude for Saints Peter, James and John to behold the glory of the Transfigured [email protected] Christ (Matt. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

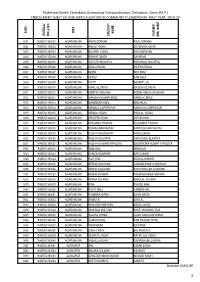

Mahatma Gandhi Chitrakoot Gramodaya Vishwavidyalaya, Chitrakoot, Satna (M.P.)

Mahatma Gandhi Chitrakoot Gramodaya Vishwavidyalaya, Chitrakoot, Satna (M.P.) ENROLLMENT SHEET OF BSW (SPECIALIZATION IN COMMUNITY LEADERSHIP) FIRST YEAR 2019-20 DIST. S.NO. NAME NAME FATHER/ ENROLL/ ROLL NO. STUDENT STUDENT HUS. NAME HUS. 0001 19/WE/01350001 AGAR MALWA ANITA GORANA RAJU GORANA 0002 19/WE/01350002 AGAR MALWA ANJALI YADAV DEVENDRA SINGH 0003 19/WE/01350003 AGAR MALWA BASANTI YADAV SHIV NARAYAN 0004 19/WE/01350004 AGAR MALWA BHARAT SINGH DAYARAM 0005 19/WE/01350005 AGAR MALWA GAYATRI MALVEYA MOHANLAL MALVEYA 0006 19/WE/01350006 AGAR MALWA GUNJA RAVAL RAJESH RAVAL 0007 19/WE/01350007 AGAR MALWA INDRA SITA RAM 0008 19/WE/01350008 AGAR MALWA JASSU RAM KALA 0009 19/WE/01350009 AGAR MALWA JYOTI BASANTI LAL 0010 19/WE/01350010 AGAR MALWA KAPIL SILORIYA RAJESH SILORIYA 0011 19/WE/01350011 AGAR MALWA MAMTA CHAUHAN KOMAL SINGH CHAUHAN 0012 19/WE/01350012 AGAR MALWA MANISHA KUMARI BENS NANDLAL BENS 0013 19/WE/01350013 AGAR MALWA NARENDRA SONI MADANLAL 0014 19/WE/01350014 AGAR MALWA NIRMALA CARPENTAR NARAYAN CARPENTAR 0015 19/WE/01350015 AGAR MALWA NIRMLA YADAV PIRULAL YADAV 0016 19/WE/01350016 AGAR MALWA PRAVEEN KHAN JAFAR KHAN 0017 19/WE/01350017 AGAR MALWA PRIYANKA THAKUR RAJENDRA THAKUR 0018 19/WE/01350018 AGAR MALWA PUNAM SHRIVASTAV SANTOSH SHRIVASTAV 0019 19/WE/01350019 AGAR MALWA PUSHPA BAGDAWAT HINDU SINGH 0020 19/WE/01350020 AGAR MALWA PUSHPA BIJORIYA HARI SINGH BIJORIYA 0021 19/WE/01350021 AGAR MALWA PUSHPA KUMARI PIPALDYA BHUPENDRA KUMAR PIPALDYA 0022 19/WE/01350022 AGAR MALWA RAMU BAI MANGILAL 0023 19/WE/01350023 AGAR