"They Shot Us Like Animals": Black November & Bolivia's Interim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of California San Diego

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Infrastructure, state formation, and social change in Bolivia at the start of the twentieth century. A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Nancy Elizabeth Egan Committee in charge: Professor Christine Hunefeldt, Chair Professor Michael Monteon, Co-Chair Professor Everard Meade Professor Nancy Postero Professor Eric Van Young 2019 Copyright Nancy Elizabeth Egan, 2019 All rights reserved. SIGNATURE PAGE The Dissertation of Nancy Elizabeth Egan is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ___________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair ___________________________________________________________ Chair University of California San Diego 2019 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS SIGNATURE PAGE ............................................................................................................ iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................... iv LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................ vii LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................... ix LIST -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

Races of Maize in Bolivia

RACES OF MAIZE IN BOLIVIA Ricardo Ramírez E. David H. Timothy Efraín DÍaz B. U. J. Grant in collaboration with G. Edward Nicholson Edgar Anderson William L. Brown NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL Publication 747 Funds were provided for publication by a contract between the National Academythis of Sciences -National Research Council and The Institute of Inter-American Affairs of the International Cooperation Administration. The grant was made the of the Committee on Preservation of Indigenousfor Strainswork of Maize, under the Agricultural Board, a part of the Division of Biology and Agriculture of the National Academy of Sciences - National Research Council. RACES OF MAIZE IN BOLIVIA Ricardo Ramírez E., David H. Timothy, Efraín Díaz B., and U. J. Grant in collaboration with G. Edward Nicholson Calle, Edgar Anderson, and William L. Brown Publication 747 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL Washington, D. C. 1960 COMMITTEE ON PRESERVATION OF INDIGENOUS STRAINS OF MAIZE OF THE AGRICULTURAL BOARD DIVISIONOF BIOLOGYAND AGRICULTURE NATIONALACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONALRESEARCH COUNCIL Ralph E. Cleland, Chairman J. Allen Clark, Executive Secretary Edgar Anderson Claud L. Horn Paul C. Mangelsdorf William L. Brown Merle T. Jenkins G. H. Stringfield C. O. Erlanson George F. Sprague Other publications in this series: RACES OF MAIZE IN CUBA William H. Hatheway NAS -NRC Publication 453 I957 Price $1.50 RACES OF MAIZE IN COLOMBIA M. Roberts, U. J. Grant, Ricardo Ramírez E., L. W. H. Hatheway, and D. L. Smith in collaboration with Paul C. Mangelsdorf NAS-NRC Publication 510 1957 Price $1.50 RACES OF MAIZE IN CENTRAL AMERICA E. -

Bolivia's 2020 Election: Winning Is Only the Beginning for Luis Arce and The

LSE Latin America and Caribbean Blog: Bolivia’s 2020 election: winning is only the beginning for Luis Arce and the MAS Page 1 of 3 Bolivia’s 2020 election: winning is only the beginning for Luis Arce and the MAS The new MAS government of Luis Arce will be caught between popular expectations of a return to relative prosperity, a growing ecological catastrophe tied to a declining economic model, and a range of social and ideological challenges that pit right-wing religious forces against an increasingly progressive younger generation. But even if the years ahead will show that this victory was in fact the easy part, for now Bolivians have given the world a vital lesson in democracy, writes Bret Gustafson (Washington University in St Louis). Though the official tally is still being finalised, exit polls released around midnight on Sunday 18 October suggest an overwhelming victory for the MAS party in Bolivia, just eleven months after the ouster of Evo Morales. To avoid a run-off, the MAS presidential candidate Luis Arce needed at least 40 per cent of the vote and a ten-point lead over his nearest rival, but this looked like anything but a foregone conclusion in the lead-up to the elections. Luis Arce and his MAS party achieved a sweeping victory just eleven months after Evo Morales was ousted from the presidency (flag removed, Cancillería del Ecuador, CC BY-SA 2.0) Pre-election polling and a divided opposition In the weeks and days before the vote, polling suggested that Carlos Mesa, a right-leaning historian who was briefly president in the early 2000s, stood a good chance of making it to the second round. -

Municipio De Patacamaya (Agosto 2002 - Enero 2003) 52

Municipio de Patacamaya (Agosto 2002 - enero 2003) Diario de Ángela Copaja En agosto Donde Ángela conoce, antes que nada, el esplendor y derro- che de las fiestas en Patacamaya, y luego se instala para comenzar a trabajar JUEVES 8. Hoy fue mi primer día, estaba histérica, anoche casi no pude dormir y esta mañana tuve que madrugar para tomar la flota y estar en la Alcaldía a las 8:30 a.m. El horario normal es a las 8:00 de la mañana, pero el intenso frío que se viene registrando obligó a instaurar un horario de invierno (que se acaba esta semana). Vine con mi mamá, tomamos la flota a Oruro de las 6:30, llegamos a Patacamaya casi a las ocho y media, y como ya era tarde, tuvimos que tomar un taxi (no sabía que habían por aquí) para llegar a la Al- caldía, pues queda lejos de la carretera. Después de dejarme en mi "trabajo" se fue a buscarme un cuarto, donde se supone me iba a quedar esa noche, pues 51 traje conmigo algunas cosas; me quedaré hoy (jueves) y mañana (viernes) me vuelvo yo solita a La Paz. Ya en la oficina tuve que esperar a que llegara el Profesor Celso (Director de la Dirección Técnica y de Planificación) para que me presentara al Alcalde. Me Revista número 13 • Diciembre 2003 condujo hasta la oficina y me presentó al Profesor Gregorio, el Oficial Mayor, un señor bastante serio que me dio hartísimo miedo pues me trató de una forma muy tosca. Él me presentó al Alcalde, que me dio la bienvenida al Mu- nicipio de Patacamaya muy amablemente. -

Web Apr 06.Qxp

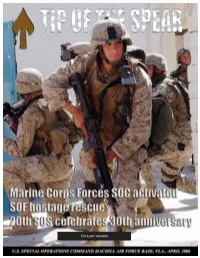

On-Line version TIP OF THE SPEAR Departments Global War On Terrorism Page 4 Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command Page 18 Naval Special Warfare Command Page 21 Air Force Special Operations Command Page 24 U.S. Army Special Operations Command Page 28 Headquarters USSOCOM Page 30 Special Operations Forces History Page 34 Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command historic activation Gen. Doug Brown, commander, U.S. Special Operations Command, passes the MARSOC flag to Brig. Gen. Dennis Hejlik, MARSOC commander, during a ceremony at Camp Lejune, N.C., Feb. 24. Photo by Tech. Sgt. Jim Moser. Tip of the Spear Gen. Doug Brown Capt. Joseph Coslett This is a U.S. Special Operations Command publication. Contents are Commander, USSOCOM Chief, Command Information not necessarily the official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government, Department of Defense or USSOCOM. The content is CSM Thomas Smith Mike Bottoms edited, prepared and provided by the USSOCOM Public Affairs Office, Command Sergeant Major Editor 7701 Tampa Point Blvd., MacDill AFB, Fla., 33621, phone (813) 828- 2875, DSN 299-2875. E-mail the editor via unclassified network at Col. Samuel T. Taylor III Tech. Sgt. Jim Moser [email protected]. The editor of the Tip of the Spear reserves Public Affairs Officer Editor the right to edit all copy presented for publication. Front cover: Marines run out of cover during a short firefight in Ar Ramadi, Iraq. The foot patrol was attacked by a unknown sniper. Courtesy photo by Maurizio Gambarini, Deutsche Press Agentur. Tip of the Spear 2 Highlights Special Forces trained Iraqi counter terrorism unit hostage rescue mission a success, page 7 SF Soldier awarded Silver Star for heroic actions in Afghan battle, page 14 20th Special Operations Squadron celebrates 30th anniversary, page 24 Tip of the Spear 3 GLOBAL WAR ON TERRORISM Interview with Gen. -

Captive Communities: Situation of the Guaraní Indigenous People and Contemporary Forms of Slavery in the Bolivian Chaco

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 58 24 December 2009 Original: Spanish CAPTIVE COMMUNITIES: SITUATION OF THE GUARANÍ INDIGENOUS PEOPLE AND CONTEMPORARY FORMS OF SLAVERY IN THE BOLIVIAN CHACO 2009 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. Comunidades cautivas : situación del pueblo indígena guaraní y formas contemporáneas de esclavitud en el Chaco de Bolivia = Captive communities : situation of the Guaraní indigenous people and contemporary forms of slavery in the Bolivian Chaco / Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5433‐2 1. Guarani Indians‐‐Human rights‐‐Bolivia‐‐Chaco region. 2. Guarani Indians‐‐Slavery‐‐ Bolivia‐‐Chaco region. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Slavery‐‐Bolivia‐‐Chaco region. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Human rights‐‐Bolivia. 5. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐ Bolivia. I. Title. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 58 Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 24, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. Canton Assistant Executive Secretary: Elizabeth Abi‐Mershed The IACHR thanks the Governments of Denmark and Spain for the financial support that made it possible to carry out the working and supervisory visit to Bolivia from June 9 to 13, 2008, as well as the preparation of this report. -

Informe Estadístico Del Municipio De El Alto

INFORME ESTADÍSTICO DEL MUNICIPIO DE EL ALTO 2020 ÍNDICE 1. Antecedentes .................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Situación demográfica ..................................................................................................................... 2 3. Situación económica ....................................................................................................................... 3 3.1 Comercio ....................................................................................................................................... 3 3.2 Industria Manufacturera ............................................................................................................... 5 3.3 Acceso a Financiamiento ............................................................................................................... 6 3.4 Ingresos Municipales por Transferencias ...................................................................................... 7 3.5 Empleo ........................................................................................................................................... 8 4. Bibliografía ....................................................................................................................................... 8 ANEXOS ................................................................................................................................................... 9 Índice de Gráficos Gráfico 1: Población -

Than a Meal: the Turkey in History, Myth

More Than a Meal Abigail at United Poultry Concerns’ Thanksgiving Party Saturday, November 22, 1997. Photo: Barbara Davidson, The Washington Times, 11/27/97 More Than a Meal The Turkey in History, Myth, Ritual, and Reality Karen Davis, Ph.D. Lantern Books New York A Division of Booklight Inc. Lantern Books One Union Square West, Suite 201 New York, NY 10003 Copyright © Karen Davis, Ph.D. 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of Lantern Books. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data For Boris, who “almost got to be The real turkey inside of me.” From Boris, by Terry Kleeman and Marie Gleason Anne Shirley, 16-year-old star of “Anne of Green Gables” (RKO-Radio) on Thanksgiving Day, 1934 Photo: Underwood & Underwood, © 1988 Underwood Photo Archives, Ltd., San Francisco Table of Contents 1 Acknowledgments . .9 Introduction: Milton, Doris, and Some “Turkeys” in Recent American History . .11 1. A History of Image Problems: The Turkey as a Mock Figure of Speech and Symbol of Failure . .17 2. The Turkey By Many Other Names: Confusing Nomenclature and Species Identification Surrounding the Native American Bird . .25 3. A True Original Native of America . .33 4. Our Token of Festive Joy . .51 5. Why Do We Hate This Celebrated Bird? . .73 6. Rituals of Spectacular Humiliation: An Attempt to Make a Pathetic Situation Seem Funny . .99 7 8 More Than a Meal 7. -

Wild Potato Species Threatened by Extinction in the Department of La Paz, Bolivia M

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Scientific Journals of INIA (Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Tecnología Agraria y Alimentaria) Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Tecnología Agraria y Alimentaria (INIA) Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2007 5(4), 487-496 Available online at www.inia.es/sjar ISSN: 1695-971-X Wild potato species threatened by extinction in the Department of La Paz, Bolivia M. Coca-Morante1* and W. Castillo-Plata2 1 Facultad de Ciencias Agrícolas, Pecuarias, Forestales y Veterinarias. Dr. «Martín Cárdenas» (FCA, P, F y V). Universidad Mayor de San Simón (UMSS). Casilla 1044. Cochabamba. Bolivia 2 Medio Ambiente y Desarrollo (MEDA). Cochabamba. Bolivia Abstract The Department of La Paz has the largest number of wild potato species (Solanum Section Petota Solanaceae) in Bolivia, some of which are rare and threatened by extinction. Solanum achacachense, S. candolleanum, S. circaeifolium, S. okadae, S. soestii and S. virgultorum were all searched for in their type localities and new areas. Isolated specimens of S. achacachense were found in its type localities, while S. candolleanum was found in low density populations. Solanum circaeifolium was also found as isolated specimens or in low density populations in its type localities, but also in new areas. Solanum soestii and S. okadae were found in small, isolated populations. No specimen of S. virgultorum was found at all. The majority of the wild species searched for suffered the attack of pathogenic fungi. Interviews with local farmers revealed the main factors negatively affecting these species to be loss of habitat through urbanization and the use of the land for agriculture and forestry. -

Nigeria's Resource Wars

NIGERIA’S RESOURCE WARS Edited by Egodi Uchendu University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria Series in World History Copyright © 2020 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200 C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware, 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in World History Library of Congress Control Number: 2020939820 ISBN: 978-1-62273-831-1 Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image designed by rawpixel.com / Freepik. Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Nigeria’s current delineation into six geo-political zones. © Egodi Uchendu 2020. Table of contents List of Figures xi List of Tables xv List of Abbreviations xvii Acknowledgements xxiii Preface xxv Egodi Uchendu University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria Introduction: The Struggle for Equitable and Efficient Natural Resource Allocation in Nigeria liii John Mukum Mbaku Weber State University, Utah, USA Part 1. -

IHRC Submission on Bolivia

VIOLATIONS OF THE RIGHT TO LIFE, RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION, RIGHT TO ASSEMBLY & ASSOCIATION, AND OTHERS: ONGOING HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BOLIVIA Submission to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions from Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic Cc: Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers Special Rapporteur on the f reedom of opinion and expression Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism The International Human Rights Clinic (IHRC) at Harvard Law School seeks to protect and promote human rights and internation-al humanitarian law through documentation; legal, factual, and stra-tegic analysis; litigation before national, regional, and internation-al bodies; treaty negotiations; and policy and advocacy initiatives. Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations to the U.N. Special Rapporteurs ........................................................................... 2 Facts ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Background on the Current Crisis ........................................................................................................ 3 State Violence Against Protesters