The Jimmy Schneider and Robert Bulmore Collection of New Almaden Mine Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diocese of San Jose 2020 Directory

Diocese of San Jose 2020 Directory 1150 North First Street, Suite 100 San Jose, California 95112 Phone (408) 983-0100 www.dsj.org updated 10/8/2020 1 2 Table of Contents Diocese Page 5 Chancery Office Page 15 Deaneries Page 29 Churches Page 43 Schools Page 163 Clergy & Religious Page 169 Organizations Page 205 Appendix 1 Page A-1 Appendix 2 Page A-15 3 4 Pope Francis Bishop of Rome Jorge Mario Bergoglio was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina's capital city, on December 17, 1936. He studied and received a master's degree in chemistry at the University of Buenos Aires, but later decided to become a Jesuit priest and studied at the Jesuit seminary of Villa Devoto. He studied liberal arts in Santiago, Chile, and in 1960 earned a degree in philosophy from the Catholic University of Buenos Aires. Between 1964 and 1965 he was a teacher of literature and psychology at Inmaculada High School in the province of Santa Fe, and in 1966 he taught the same courses at the prestigious Colegio del Salvador in Buenos Aires. In 1967, he returned to his theological studies and was ordained a priest on December 13, 1969. After his perpetual profession as a Jesuit in 1973, he became master of novices at the Seminary of Villa Barilari in San Miguel. Later that same year, he was elected superior of the Jesuit province of Argentina and Uruguay. In 1980, he returned to San Miguel as a teacher at the Jesuit school, a job rarely taken by a former provincial superior. -

![National Register of Historic Places I ] §Gp Registration Form I](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1130/national-register-of-historic-places-i-%C2%A7gp-registration-form-i-881130.webp)

National Register of Historic Places I ] §Gp Registration Form I

(Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places I ] §gp Registration Form i • _ _„_....—•- This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. ?See instructions in Hovy to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete eaihJtem by marking"x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicaole." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property________________________________________RELt^Fn/r''!^ historic name Alviso, Jose Maria, Adob°—————————————— other names/site number CA-SC1 -15? ___________________ 2. Location street & number Q? P-jprfmnnt- Pnari ___________________________ G not for publication city or town Mi Ip-it-ac;_____________________________________ D vicinity state ______rj=n -ifn-rnia code CA county fianivi ria-ra_____ code ngc; zip code 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, 1 hereby certify that this^Q nomination Q request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property S3 meetdlO does not meet the National Register criteria 1 recommend that this property be considered significant d nationally £H stat§wid^ Q/tocally. -

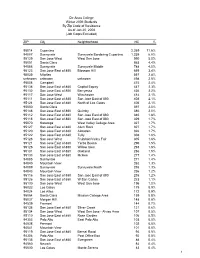

Students by Zip Code of Residence As of Jan 20, 2006 (Job Corps Excluded)

De Anza College Winter 2006 Students By Zip Code of Residence As of Jan 20, 2006 (Job Corps Excluded) ZIP City Neighborhood HC % 95014 Cupertino 2,269 11.6% 94087 Sunnyvale Sunnyvale Bordering Cupertino 1,339 6.8% 95129 San Jose West West San Jose 990 5.0% 95051 Santa Clara 863 4.4% 94086 Sunnyvale Sunnyvale Middle 788 4.0% 95123 San Jose East of 880 Blossom Hill 659 3.4% 95035 Milpitas 557 2.8% unknown unknown unknown 498 2.5% 95008 Campbell 474 2.4% 95136 San Jose East of 880 Capitol Expwy 447 2.3% 95132 San Jose East of 880 Berryessa 436 2.2% 95117 San Jose West Winchester 414 2.1% 95111 San Jose East of 880 San Jose East of 880 408 2.1% 95124 San Jose East of 880 North of Los Gatos 406 2.1% 95050 Santa Clara 397 2.0% 95148 San Jose East of 880 Quimby 386 2.0% 95112 San Jose East of 880 San Jose East of 880 346 1.8% 95118 San Jose East of 880 San Jose East of 880 329 1.7% 95070 Saratoga West Valley College Area 327 1.7% 95127 San Jose East of 880 Alum Rock 327 1.7% 95120 San Jose East of 880 Almaden 326 1.7% 95122 San Jose East of 880 Tully 308 1.6% 95128 San Jose West Fruitdale/Valley Fair 305 1.6% 95121 San Jose East of 880 Yerba Buena 296 1.5% 95125 San Jose East of 880 Willow Glen 293 1.5% 95131 San Jose East of 880 Oakland 286 1.5% 95133 San Jose East of 880 McKee 277 1.4% 94085 Sunnyvale 271 1.4% 94040 Mountain View 262 1.3% 94089 Sunnyvale Sunnyvale North 255 1.3% 94043 Mountain View 236 1.2% 95116 San Jose East of 880 San Jose East of 880 235 1.2% 95126 San Jose East of 880 W San Carlos 223 1.1% 95130 San Jose West West San -

The Bond Between Boba and Asian American Youth in San José, Califor

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “Wanna Get Boba?”: The Bond Between Boba and Asian American Youth in San José, California A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Asian American Studies by Talitha Angelica Acaylar Trazo 2020 © Copyright by Talitha Angelica Acaylar Trazo 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS “Wanna Get Boba?”: The Bond Between Boba and Asian American Youth in San José, California by Talitha Angelica Acaylar Trazo Master of Arts in Asian American Studies University of California, Los Angeles 2020 Professor Victor Bascara, Chair The tenth largest city in the United States with a population of over 1 million, San José, California resides on the southernmost edge of the Silicon Valley. Though high-tech narratives often subsume this region, a closer examination of San José’s (sub)urban landscape reveals the presence of over 100 boba shops and their multiethnic community of local patrons. Boba, a milk tea beverage which originated in Taiwan in the 1980s, made its U.S. debut in the late 1990s when Taiwanese American entrepreneurs aimed to emulate Taiwan’s unique boba shop experience in their American hometowns. Over the past 20 years, boba within the United States has morphed into a distinctly Asian American cultural phenomenon, which I argue makes boba a unique lens by which to examine Asian American youth culture. For this ethnographic study, I conducted and analyzed 17 interviews and 156 survey responses from Bay Area-based young adults (between the ages of 18 and 40) with varying degrees of familiarity with San José boba ii shops: from the occasional boba drinker to what some may call the “boba addict.” I opened the survey to all racial groups but focused my data analysis on those who self-identified as Asian American. -

WE FOUND OUR WAY to SAN JOSE CA NV Chapter Symposium 2006 JOHN MARSH HISTORIC TRUST TOUR

WE FOUND OUR WAY TO SAN JOSE JOHN MARSH HISTORIC CA NV Chapter Symposium 2006 TRUST TOUR By Carol March The John Marsh Trust will host a limited number of May 6 and 7, 2006 provided perfect weather visitors (less than 100) for a tour and walk about the John and San Jose, California provided many interesting Marsh House on Saturday, June 3, 2006. Time: 11:00 am. historic sites as members and friends of the Califor- Sharp. A box lunch will be provided after the one hour tour. nia-Nevada Chapter of OCTA gathered for the annual Members of the John Marsh Historic Trust will be Spring Symposium. Early on Saturday morning we on hand to provide information on the latest efforts to met at the Holiday Inn Silicon Valley in South San save the historic house. California Parks and Jose for Registration, continental breakfast and time to Recreation Site Manager/Ranger, Craig Mattson, will get acquainted before the day's programs began. Mary provide the access and comments. RSVP to Kathleen Mueller, chairman of the Symposium, welcomed us Mero, Treasurer, John Marsh Historic Trust, at email: and filled us in on the day's activities, then off we [email protected]. went to the first event. This is a thank you to the many "Friends" of John Awaiting us in the White Oak Room was a Marsh. No charge for the tour or for lunch. Limited ac- wonderful group of musicians directed by Lance Bee- cess. You must RSVP and have your name on the admis son and narrated by Greg P. -

Polychlorinated Biphenyls (Pcbs) in San Francisco Bay$

ARTICLE IN PRESS Environmental Research 105 (2007) 67–86 www.elsevier.com/locate/envres Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in San Francisco Bay$ J.A. Davisa,Ã, F. Hetzelb, J.J. Orama, L.J. McKeea aSan Francisco Estuary Institute, 7770 Pardee Lane, Oakland, CA 94621, USA bSan Francisco Regional Water Quality Control Board, 1515 Clay Street, Suite 1400, Oakland, CA 94612, USA Received 14 September 2005; received in revised form 27 December 2006; accepted 31 January 2007 Available online 23 April 2007 Abstract San Francisco Bay is facing a legacy of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) spread widely across the land surface of the watershed, mixed deep into the sediment of the Bay, and contaminating the Bay food web to a degree that poses health risks to humans and wildlife. In response to this persistent problem, water quality managers are establishing a PCB total maximum daily load (TMDL) and implementation plan to accelerate the recovery of the Bay from decades of PCB contamination. This article provides a review of progress made over the past 15 years in managing PCBs and understanding their sources, pathways, fate, and effects in the Bay, and highlights remaining information needs that should be addressed in the next 10 years. The phaseout of PCBs during the 1970s and the 1979 federal ban on sale and production led to gradual declines from the 1970s to the present. However, 25 years after the ban, PCB concentrations in some Bay sport fish today are still more than ten times higher than the threshold of concern for human health. Without further management action it appears that the general recovery of the Bay from PCB contamination will take many more decades. -

Diocese of San Jose 2019 Directory

Diocese of San Jose 2019 Directory 1150 North First Street, Suite 100 San Jose, California 95112 Phone (408) 983-0100, Fax (408) 983-0295 www.dsj.org updated 1/30/2019 1 2 Table of Contents Diocese Page 5 Chancery Office Page 15 Deaneries Page 29 Churches Page 43 Schools Page 163 Clergy & Religious Page 169 Organizations Page 205 Appendix 1 Page A-1 Appendix 2 Page A-15 3 4 Pope Francis Bishop of Rome Jorge Mario Bergoglio was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina's capital city, on December 17, 1936. He studied and received a master's degree in chemistry at the University of Buenos Aires, but later decided to become a Jesuit priest and studied at the Jesuit seminary of Villa Devoto. He studied liberal arts in Santiago, Chile, and in 1960 earned a degree in philosophy from the Catholic University of Buenos Aires. Between 1964 and 1965 he was a teacher of literature and psychology at Inmaculada High School in the province of Santa Fe, and in 1966 he taught the same courses at the prestigious Colegio del Salvador in Buenos Aires. In 1967, he returned to his theological studies and was ordained a priest on December 13, 1969. After his perpetual profession as a Jesuit in 1973, he became master of novices at the Seminary of Villa Barilari in San Miguel. Later that same year, he was elected superior of the Jesuit province of Argentina and Uruguay. In 1980, he returned to San Miguel as a teacher at the Jesuit school, a job rarely taken by a former provincial superior. -

Supplement to the Soil Survey of Santa Clara Area, California, Western Part

United States Department of Agriculture Supplement to the Natural Soil Survey of Resources Conservation Service Santa Clara Area, California, Western Part National Cooperative Soil Survey This document was made for the National Cooperative Soil Survey by the United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, in cooperation with the Regents of the University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources (Agricultural Experiment Station); the Guadalupe-Coyote Resource Conservation District; the Mid-Peninsula Regional Open Space District; the Santa Clara County Parks and Recreation Department; the Santa Clara County Open Space Authority; and Stanford University. This supplement accompanies the most current official data for the soil survey of the Santa Clara Area, California, Western Part, available at http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/. Acknowledgement is also given to the many cities and towns within the survey area who granted permission for the soil survey to be conducted on their public lands. These include Campbell, Cupertino, Los Altos, Los Altos Hills, Los Gatos, Milpitas, Mountain View, Palo Alto, Santa Clara, San Jose, Saratoga, and Sunnyvale. This document is part of the technical assistance furnished by the Natural Resources Conservation Service, Hollister, California Office to the Guadalupe-Coyote Resource Conservation District. Literature Citation The correct citation for this survey is as follows: United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2015. Supplement to the Soil Survey of the Santa Clara Area, California, Western Part. (Accessible online at: http://soils.usda.gov/survey/printed_surveys/) Cover Caption View looking southeast across the cities of the Santa Clara Valley to the Diablo Ranges and Santa Cruz Mountains. -

Silicon Valley Images of America" Author: Sam Shueh Call Number: 979.473 S56 Indexed by Shirley Hunt

Index for "Silicon Valley Images of America" Author: Sam Shueh Call number: 979.473 S56 Indexed by Shirley Hunt Last Name/Place First Name page # Image type Other information 1890 ledger shows School expense Evergreen 40 photo Adobe headquarters San Jose San Jose 108 photo Founded 1982 to make desktop publishing software Aerial view of Sunnyvale 1940 Sunnyvale 57 photo Agnew clock tower rebuilt after 1906 Agnew Village 70 photo Well known as mental hospital until 1960s Agnew Development Center 1887 Agnew Village 68 photo Construction in process Agnew Development Center 1888 Agnew Village 68 photo Construction nearly complete Air intake on subsonic wind tunnel Mountain View 54 photo Current Alviso Port used for supply transport Alviso 112 photo Later used for yachts Amdahl Gene 2 photo 1963 IBM event demo of S/360 mainframe computer Apple Computer ad Apple-1 Cupertino 105 photo Photo 1976 Apple headquarters 1 Infinite Loop Cupertino 82 photo Apple release of iPhone NY store New York 106 photo People stood in line overnight before the release Assorted disk drives from startups Santa Clara 103 photo Computer Museum Assorted PCs created by companies Santa Clara 103 photo Computer Museum Babbage computer demonstrated Mountain View 92 photo Computer Museum Bank of Italy 1st and 2nd street San Jose 89 photo Photo 1890 Bank of Italy 1st and Santa Clara St. San Jose 89 photo Photo 1930s Bankrupt corporate property Mountain View 55 photo Bicycle race, 35th Annual Los Gatos 126 photo Photo 2008 Blackberry Farm golf course Santa Clara 77 photo Photo current day Bombers parked outside hangars Moffett Field 50 photo Bookmobile in Almaden garage 1967 Santa Clara County 116 photo Bubb family gathering Cupertino 86 photo Photo 19th century C.J. -

August 2014 Santa Clara County Calworks Resource Guide

CalWORKs Resource Guide Santa Clara County Making a Difference Through People, Service and Performance! August 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Find the Guide on Line at: http://www.sccgov.org/sites/ssa/Department%20of%20Employment%20- %20Benefit%20Services/Pages/Department-of-Employment---Benefit-Services.aspx EMERGENCY RESOURCES HEALTH RESOURCES- CONTINUE Emergency Assistance Network 1 Black Infant Health Program 24 Community Services Agency of Mt. View & Los Altos All Around Senior Services 24 The Salvation Army CalWORKs Health Alliance 25 St. Joseph’s Family Center YMCA – Mental Health Services 25 Sunnyvale Community Services Rebekah – Children’s Services 26 Sacred Heart Community Services Healthier Kids Foundation Santa Clara County 26 Santa Clara InnVision Georgia Travis Center Mental Health Call Center – Counseling Services 27 InnVision Opportunity Services Center Goodwill of Silicon Valley – Wellness Center 27 County Social West Valley Community Services Suicide Prevention 27 Cal-Learn/AFLP Programs – Pregnant Teen Services 28 COUNTY OF SANTA CLARA Services Agency Alum Rock Counseling Center 28 Social Services Agency – Benefits Information 2-3 Mission DOMESTIC VIOLENCE RESOURCES SUPPORT RESOURCES CalWORKs Social Work Unit 29 Statement: 2-1-1 – Santa Clara County 4 Domestic Violence Prevention 29 VITA – Volunteer Income Tax Assistance 4 Next Door Solutions to Domestic Violence 29 Bay Area Self-Sufficiency Calculator 5 The Social YMCA Domestic Violence Dept. Support Network 29 Bay Area Legal Aid 5 Services Agency Sacred Heart Community -

January 2011 Newsletter

SARATOGA HISTORICAL FOUNDATION PO BOX 172, SARATOGA, CALIFORNIA 95071 January 2011 Don’t miss the free lecture on New Almaden January 17; New exhibit on woman’s suffrage opening February 6; Check out the Mustard Faire March 6; Don’t miss the March 21 lecture on Sarah Winchester; And renew your membership today !!!! scare halted the last attempts to reduce the still potentially New Almaden—Once the Largestprofitable Quicksilver cinnabar. Boudreault Minenotes information in California--Free Lecture “The History of New Almaden—Once the Largest Was discovered and this issue will be included in the Quicksilver Mine in California” will be presented on presentation. Monday, January 17 by noted authors and local historians The New Almaden Quicksilver Mine produced over $75 Art Boudreault and Mike Boulland. million from some of the deepest network of quicksilver The program will take place on January 17, at 7:15 PM. shafts on earth. Diverse laborers populated this thriving Those participating in the potluck dinner should arrive at town, creating neighborhoods called Hacienda, Englishtown, 6:30 PM and bring food to share, your own dishes and eating and Spanishtown along with the mine manager’s stately utensils. Beverages of water, tea or coffee will be provided. home, Casa Grande. Although the mines are now closed and The Immanuel Lutheran Church is located at 14103 Saratoga the great ore furnace cold, the Casa Grande still stands along Avenue in Saratoga. The with a residential community that event is free and open to the was placed on the National public. Register of Historic Places in New Almaden is located 1963. -

Santa Clara-San Jose City Guide

San Jose, California San Jose, California Overview Introduction San Jose, California, is more than just the unofficial capital of Silicon Valley, the place where the U.S. computer industry took off and created a high-technology world. Palm trees and luxury hotels line busy boulevards in lively downtown San Jose, and the city's trendy restaurants, classy shops and lively nightspots attract both visitors and locals, including many who work in the world of technology. Despite its sudden growth during the tech boom of the 1990s, San Jose retains its small-town charm. Highlights Sights—The strange and beautiful Winchester Mystery House; the historic Peralta Adobe and Fallon House; the Montalvo Arts Center. Museums—The amazing interactive exhibits at The Tech Museum of Innovation; masterworks at the San Jose Museum of Art; the large collection of Egyptian artifacts at the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum & Planetarium. Memorable Meals—The enchanting ambience and French fare at La Foret Creekside Dining; the funky atmosphere of Henry's Hi-Life. Late Night—Drinking and dancing at San Jose Bar and Grill; live music at JJ's Lounge. Walks—A hike in nearby Alum Rock Park; Santa Cruz Mountains in Portola Redwoods State Park; a stroll along the boardwalk at Santa Cruz Beach; a rose-scented walk through Guadalupe River Park & Gardens; a hike in the hillside trails around the Montalvo Arts Center. Especially for Kids—The Children's Discovery Museum of San Jose; Happy Hollow Park and Zoo. Geography San Jose is in the Santa Clara Valley, otherwise known as Silicon Valley. It is bordered by two mountain ranges, the Santa Cruz Mountains to the west and the Diablo Range to the east.