The Good Brexiteer's Guide to English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noel Gallagher Meets Tim Jonze

“ I’ve got one fatal fl aw in my perfect makeup as a human being. I never forgive Noel Gallagher meets Tim Jonze Monday 05/08/19 Four pages of wellbeing! Rhik Samadder, how to say sorry and life without soap pages 2-5 Re-enter the dragon How Bruce Lee’s daughter brought his dream to life page 10 • The Guardian 2 Wellbeing Monday 5 August 2019 In Britain, we over-apologise out of politeness . Are you doing That not only detracts from an apology when we do have something to be sorry for, but it can be seen as it right? submission, especially in our professional lives. The classic example is at a social gathering or Sayingyg sorry y networking event . If you try to infi ltrate a group by saying, “sorry to interrupt” , the fi rst thing you have told people is that you are apologetic and interrupting . Likewise, people responding to emails with “sorry for the delay in getting back to you” are highlighting the fact there was a delay. Instead, start by thanking the person for allowing you the time to come back to them. In terms of saying sorry when you have something to apologise for, it is better to do it succinctly . You can tell a sincere apology by the fact that it is short and to the point. Qualifying an apology generally means the apologiser does not fully mean it. Preferably, the apology should be face to face ; if that is not possible, then do it over the phone. If you have really annoyed someone and done the initial apology face-to-face or over the phone, it is fi ne to follow up with something more expansive in writing. -

P40 Layout 1

Dior oozes ‘bourgeois cool’ at Paris men’s fashion week MONDAY, JUNE 29, 2015 38 An Iraqi vendor sells fruit in a street in the capital Baghdad during Islam’s holy month of Ramadan yesterday.—AFP Kanye gives defiant performance at Glastonbury anye West gave a defiant performance at Glastonbury on Saturday night, challenging critics Kwho said he was unsuitable for the event by declar- ing himself the “greatest living rock star”. The US rapper delighted many core fans with a 100-minute set on the Pyramid Stage that included big hits and new material, but did little to win over those festival-goers who came along out of curiosity. Wearing blue denim with a white splat- tered paint effect, West spent most of the set alone on a bare stage under a ceiling of hundreds of powerful spot lights, although he took a trip above the stage in a crane for “Touch the Sky”. “Thank you all for coming out tonight, thank you for coming to see me,” he said in a rare moment of engage- ment with the crowd. West’s performance opened with “Stronger” and closed with “Gold Digger”, and included a guest appearance by Justin Vernon of folk band Bon Iver, who lurked in the shadows on the edge of the stage as the rapper strode around. At one point, West sang part of Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody”-a bold move before declar- ing: “You are watching the greatest living rock star on the planet!” The decision to give West the coveted Saturday night Kanye West performs on The Pyramid Stage at the Glastonbury Festival, at Worthy Farm in Somerset, England, Saturday.—AP photos slot caused controversy among fans of the festival, which is better known for its rock and folk music, and 135,000 peo- ple signed a petition to get him dropped. -

May All Our Voices Be Heard

JUST THE TONIC EDFRINGE VENUES 2019 FULL LISTINGS AND MORE 1st - 25th August 2019 EDINBURGH FRINGE PROUDLY SPONSORED BY NO ONE - TOTALLY INDEPENDENT 7 venues 8 Bars 4000 performances 98.9%* 19 performance spaces 182 shows comedy *THE OTHER 1.1% ARE FUN AS WELL… CHALLENGE: GO FIND THE OTHER 2 SHOWS INSIDE! MAY ALL OUR VOICES BE HEARD www.justthetonic.com Big Value is the best Big Value compilation show at The Fringe. It’s an Comedy Shows excellent barometer of The longest running stand up compilation show on the fringe. We ask promoter people who are going Darrell Martin to take a look at at it’s fine heritage. to go on to big things. Starting in 1996, with a line up that included The show is currently produced by Darrell And I’m not just saying Milton Jones and Adam Bloom, the Big Value Martin, who runs Just the Tonic. It wasn’t Comedy Shows have been selecting the always that way. Many years ago Darrell was that because I did it. stars of the future for almost 25 years. a keen performer that was desperate to be part of the show. Comedians such as Jim Jeffries, Pete Harris was the person who set it all up. Sarah Millican, Jon Richardson and He ran a chain of clubs called Screaming ROMESH Romesh Ranganathan are some of Blue Murder. According to Adam Bloom, it all RANGANATHAN came out of a conversation where Adam said Big Value Comedy Show 2011 + 2012 those who were first exposed to the to Pete that he wanted to go to Edinburgh but couldn’t afford it. -

Autumn / Winter 2014 Box Office: 01329 223100

Autumn / Winter 2014 box office: 01329 223100 www.ashcroft.org.uk www.hants.gov.uk Visit some of these other cultural venues across South East Hampshire Across South East Hampshire, there is a wide range of exciting museums and venues for the whole family to enjoy. Westbury Manor SEARCH Eastleigh Museum Bursledon Museum The Search Hands-on centre is Discover Eastleigh’s past. Windmill part of the Gosport Discovery There is always something Fareham’s local museum, tells Visit this restored ‘tower’ mill Centre, providing exciting new to see with a regularly the story of the Borough. Set in and discover how the windmill encounters with real museum changing programme of a fabulous Georgian building, works. You can also explore the collections. special exhibitions, workshops, the museum is right in the heart other buildings on the site. www.hants.gov.uk/museum- talks and events, plus family of Fareham. www.hants.gov.uk/windmill search friendly attractions. www.hants.gov.uk/westbury- www.hants.gov.uk/eastleigh- manor-museum museum 2 Welcome to the Ashcroft Diary of Events September Lee Nelson Wed 17 £17 7.30pm Comedy November Kris Drever & Eamonn Coyne Thurs 18 £14/£13 7.30pm Music A November Day Thurs 6 £12/£11 7.30pm Theatre I Believe in Unicorns Sat 20 £7/Family £22 11.30am & 2.30pm Theatre The Hut People Fri 7 £12/£11 7.30pm Music Tom Stade Wed 24 £16 7.30pm Comedy Philip Henry & Hannah Martin Sat 8 £12/£11 7.30pm Music Martin Carthy & Dave Swarbrick Thurs 25 £14/£13 7.30pm Music James Acaster Wed 12 £13/£10 7.30pm Comedy Son Yambu Fri 26 -

Download Nabokov Season Autumn2009

EVERYONE WE’VE EVER WORKED WITH EVER PLAYWRIGHTS: Bola Agbaje, Michael Andrews, Van Badham, Mike Bartlett, Helen Blakeman, Oleg Bogaev, Justin Butcher, Glyn Cannon, James Cawood, In-Sook Chappell, Marcus Condron, Sam Crane, Sarah Daggar-Nickson, April De Angelis, Joan Didion, David Dipper, John Donnelly, Katie Douglas, Dave Florez, Robin French, James Graham, Stacey Gregg, Jamie Harper, Matt Hartley, James Holmes, Joel Horwood, Guy Jones, Colette Kane, Fin Kennedy, Steve Keyworth, Dawn King, Lucy Kirkwood, Morgan Lloyd Malcolm, Duncan Macmillan, Patrick Marber, Michael McLean, Rhys McClelland, DC Moore, Tom Morton-Smith, Chloë Moss, Pip Nixon, Lois Norman, Lizzie Nunnery, Ben Ockrent, Gary Owen, Drew Pautz, Phil Porter, Tim Price, Leo Richardson, Adriano Shaplin, Al Smith, Gavin Stevenson, Tena Stivicic, Jack Thorne, Jennifer Tuckett, Rachel Wagstaff, Ché Walker, Jess Walters, David Watson, Edmund White, Joy Wilkinson, Laurence Wilson, James Wilton, Alexandra Wood, Nicholas Wright, Jeff Young DIRECTORS: Phoebe Barran, Charlotte Bennett, Hannah Berrigan, Noah Birkstead-Breen, Gemma Bodinetz, Nathan Curry, Ed Curtis, Matthew Dunster, Jennie Fellows, Polly Findlay, Lucy Foster, Elizabeth Freestone, Nic Fryer, Jamie Harper, Tamara Harvey, Kirsty Houseley, Vicky Jones, Naomi Jones, Oliver Jones, Lucy Kerbel, Michael Longhurst, Will Mortimer, Nick Moss, Hamish Pirie, Mahlon Prince, Josie Rourke, Lisa Spirling, Psyche Stott, Sarah Tipple, Zoe Waterman, Tiffany Watt-Smith, Tara Wilkinson PRODUCERS: Emma Brunjes, Suzanne Carter, Sally Christopher, -

21 July 2017 Page 1 of 8

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 15 – 21 July 2017 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 15 JULY 2017 Burying The Typewriter is Carmen Bugan©s memoir of growing SAT 07:30 Painting the Clouds with Sunshine (b0076vq0) up in Romania in the 1970s and 1980s when the country was Episode 3Jazz musician and broadcaster Humphrey Lyttelton SAT 00:00 Paradise Lost in Cyberspace (b007jpgs) governed by Ceausescu, and his network of agents and informers, explores the troubled world of British band leaders after 1945. Episode 5Now a fully-fledged OAP, George Smith is set for a the Securitate, exerted a malign influence in every sphere of From November 2005. special mission with Andrea Sunbeam and Mrs Cookson. society. SAT 08:00 The Noble Years (b08y6wtz) Colin Swash©s dystopian comedy stars Stephen Moore as George, Carmen Bugan was educated at the University of Michigan (Ann "You can©t have suspense without information" - Alfred Patsy Byrne as Doris, Geoffrey McGivern as O©Connell, Edna Arbor) and Balliol College, Oxford, where she was awarded a Hitchcock on making films Dore as Mrs Cookson, Lorelei King as Andrea Sunbeam, Melanie doctorate. Her first book of poetry, Crossing The Carpathians, "At first I thought they©re going to need subtitles in the picture" - Hudson as Wilma P Random. With Christopher, Lewis MacLeod was published by Oxford Poets/Carcanet in 2004. Shelley Winters on Michael Caine©s cockney accent in ©Alfie©. and Peter Serafinowicz. "A beautiful, vivid memoir..." "Milligan and I are both manic depressives" - Peter Sellers. Producer: Richard Wilson. The Guardian Alfred Hitchcock, Shelley Winters, Peter Sellers, Sammy Davis First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 1998. -

Windsor Maidenhead LONDON’S COUNTRY ESTATE&

ROYAL BOROUGH OF WINDSOR MAIDENHEAD LONDON’S COUNTRY ESTATE& OFFICIAL 2020 VISITOR GUIDE WWW.WINDSOR.GOV.UK ROYAL BOROUGH OF WINDSOR Contents MAIDENHEAD MAPS & FEATURES INFORMATION LONDON’S COUNTRY ESTATE OFFICIAL 2020 VISITOR GUIDE& 02 40 66 48 Hours in Adrenaline-pumping, Annual Events Windsor heart-racing, Programme 2020 high-octane fun! Crowned by Windsor Castle and linked by the River Thames, the Royal Borough of Windsor & Maidenhead has a rich mix of history, culture, heritage and fun. With 04 46 73 Iconic A Beginner’s Guide Getting Here & internationally renowned events, superb shopping and dining and a range of accommodation Windsor & Eton to Eton College Getting Around to suit all tastes, this is one of England’s most famous short break destinations. 10 48 80 Windsor Castle & Glorious Gardens Royal Borough Frogmore House & Beautiful Map Landscapes 54 83 16 WITH SO MUCH TO ENJOY “ Child’s Play Where to Shop A Guide to Attractions in AND EXPERIENCE WHY Windsor & Eton Map “ 22 56 84 NOT STAY A FEW DAYS? London’s Where to Eat Quick Reference Country Estate Guide 36 62 The Perfect A Night Getaway on the Town FURTHER FACEBOOK: www.facebook.com/visitwindsoruk INFORMatioN TWITTER: twitter.com/visitwindsor www.windsor.gov.uk INSTAGRAM: #visitwindsoruk Cover images courtesy of Jodie Humphries, Design: www.ice-experience.co.uk All details in this guide were believed correct at the time of printing. Gill Aspel, Halid Izzet & Edward Staines Contents 01 Hours in 48 Windsor 01 & Eton With so much to see and do in Windsor, why not make a weekend of it? You can’t say the word Windsor without conjuring up images of the world’s oldest and largest inhabited castle, royalty, horseracing, changing the guard, the River Thames and Eton College. -

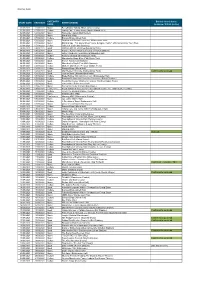

Date End Date Category Name Event

Classified: Public# CATEGORY Behind closed doors / START DATE END DATE EVENT (VENUE) NAME Audience / Virtual (online) 01/09/2021 12/09/2021 Music Everybody's Talking About Jamie (Lowry) 01/09/2021 01/09/2021 Culture Jimmy Carr: Terribly Funny (Apollo Manchester) 02/09/2021 02/09/2021 Music Passenger (Apollo Manchester) 02/09/2021 02/09/2021 Music Black Midi (Ritz) 03/09/2021 03/09/2021 Culture Bongos Bingo (Albert Hall) 03/09/2021 03/09/2021 Music Dr Hook with Dennis Locorriere (Bridgewater Hall) 03/09/2021 03/09/2021 Music Black Grape - "It's Great When You're Straight... -

View Brochure

What’s On Summer 2020 BOX OFFICE: 01295 279002 www.themillartscentre.co.uk “Provides at least three outright laughs per minute” British Theatre Guide Thursday 19th March at 7:30pm Tickets £16 | Members £13 #jeevestour jeevesandwooster.co.uk Page 2 www.themillartscentre.co.uk jeeves.indd 1 24/02/2020 14:06:48 Welcome & Thank You On behalf of the team at The Mill I am delighted to welcome you to our first brochure of 2020 and to share our latest season of events and activities. Before we roll full steam into 2020 it’s We are thrilled to welcome award-winning always a good moment to look back on the choreographer Seeta Patel to The Mill in year just passed, and what a year it’s been! June. Taking the South Indian classical We’ve seen a fantastic 34% increase in dance form of Bharatanatyam with its ticket sales with over 20,000 people seeing intricate rhythmic footwork, Seeta has or taking part in one of our many shows, created a compelling East meets West classes and off-site events in both Banbury retelling of the iconic Rite of Spring, and Bicester. showcasing some of the finest Indian classical dance talent set against Igor As an independent charity we are reliant Stravinsky’s sumptuous score. on income from ticket sales as well as from fundraising which enables us to offer an Harry Potter fans young and old will delight ever-broader range of opportunities to in the entirely improvised Spontaneous encourage everyone in our community Potter promising a hilarious, magical to learn and take part, have fun and be comedy taking inspiration from audience inspired. -

BBC Statements of Programme Policy 2010/2011 2

BBC Statements of Programme Policy 2010/2011 These Statements cover the year from April 2010 to March 2011 Contents Director-General’s statement....................................................................... 3 Television ...................................................................................................... 4 BBC One ....................................................................................................................................... 4 BBC One Scotland Annex ............................................................................................................. 9 BBC One Wales Annex ............................................................................................................... 11 BBC One Northern Ireland Annex ............................................................................................... 13 BBC Two ..................................................................................................................................... 15 BBC Two Scotland Annex ........................................................................................................... 19 BBC Two Wales Annex ............................................................................................................... 21 BBC Two Northern Ireland Annex ............................................................................................... 23 BBC Three.................................................................................................................................. -

Soul Circus 2021.Pdf

OUR PARTNERS HUMAN FAMILY I note the obvious differences in the human family. MYA ANGELOU Some of us are serious, some thrive on comedy. Some declare their lives are lived as true profundity, and others claim they really live the real reality. The variety of our skin tones can confuse, bemuse, delight, brown and pink and beige and purple, tan and blue and white. I’ve sailed upon the seven seas and stopped in every land, I’ve seen the wonders of the world not yet one common man. TRANSFORM YOUR PRACTICE WITH OUR I know ten thousand women called Jane and Mary Jane, but I’ve not seen any two Truly Revolutionary Yoga Mats who really were the same. Mirror twins are different although their features jibe, WHAT SETS LIFORME MATS APART? and lovers think quite different thoughts while lying side by side. We love and lose in China, we weep on England’s moors, and laugh and moan in Guinea, and thrive on Spanish shores. We seek success in Finland, are born and die in Maine. In minor ways we differ, in major we’re the same. I note the obvious differences between each sort and type, but we are more alike, my friends, than we are unalike. Ultimate Grip for your Truly Planet Friendly The Original & Unique practice & Body Kind Alignment System We are more alike, my friends, Even when sweaty-wet! PVC-free & biodegradable Your navigational tool than we are unalike. We are more alike, my friends, than we are unalike. liforme.com 2022 TICKETS BOOK YOUR 2022 ADVENTURE WITH US BY PURCHASING A SUPER EARLY BIRD TICKET FOR 2022 AVAILABLE AT THE FRONT OF HOUSE. -

April 2020 ... the Creative Heart of the Community

Theatre l Music l Dance l Film l Exhibitions l Workshops January - April 2020 ... the creative heart of the community Transform your Arts Centre What’s On Welcome to our Spring Season! We are opening the doors at Queen’s Hall Arts Centre to invite 04 January everyone inside for our exciting Spring Season. We have a wonderful array of performances and experiences to really lift 06 February your spirits after a long dark winter. 13 March Spring is definitely the time for something new whether it is 19 April Green Eggs and Ham, the Opera or GUY: A New Musical. Or 25 Exhibitions a beautiful new play – Robin and Rose – created through a 26 The Queen’s Club partnership between Queen’s Hall Arts, Tynedale Hospice at Home and Mad Alice Theatre Company. Bring along the family 26 Queen’s Hall Cafe to enjoy traditional tales, with a new twist, from Lempen 26 Queen’s Hall Digital Puppet Theatre and Kitchen Zoo or laugh your way through 27 Courses & Workshops Gonzo Moose’s crazy tale. And why should children have all 28 Seating Plan the fun? Book a place on our trapeze workshop! 29 Booking your Tickets We are absolutely thrilled to announce the development Thanks to funding from Arts Council England, we of a brand new Studio Theatre here at Queen’s Hall with are aiming to transform the Queen’s Hall Arts Centre 30 Season’s Diary the support of a capital grant from Arts Council England. through the creation of a brand new studio space. The Opening Doors Project will see the creation of a flexible A fully accessible and well equipped studio, space for performance, workshops and exhibitions as well as on the site of the existing Green Room will enable us ensuring that all our performance spaces and dressing rooms to offer you a broader range of shows and exhibitions, are accessible.