Exploring Justitia Through Éowyn and Niobe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

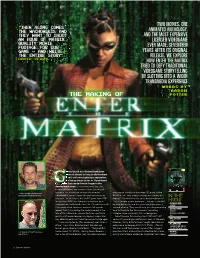

The Making of Enter the Matrix

TWO MOVIES. ONE “THEN ALONG COMES THE WACHOWSKIS AND ANIMATED ANTHOLOGY. THEY WANT TO SHOOT AND THE MOST EXPENSIVE AN HOUR OF MATRIX LICENSED VIDEOGAME QUALITY MOVIE FOOTAGE FOR OUR EVER MADE. SEVENTEEN GAME – AND WRITE YEARS AFTER ITS ORIGINAL THE ENTIRE STORY” RELEASE, WE EXPLORE DAVID PERRY HOW ENTER THE MATRIX TRIED TO DEFY TRADITIONAL VIDEOGAME STORYTELLING BY SLOTTING INTO A WIDER TRANSMEDIA EXPERIENCE Words by Aaron THE MAKING OF Potter ames based on a licence have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It’s an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with » Shiny Entertainment founder and making a fun, interactive version of a beloved working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called former game director David Perry. Hollywood IP weren’t given the time necessary to Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the IN THE succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 project.” David chalks this up as being high on his for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a “list of terrible career decisions”, though it wouldn’t KNOW single person and helped cause the US industry crash. be long before he and his team would be given a PUBLISHER: ATARI After every crash, however, comes a full system second chance. They could even use this pioneering DEVELOPER : reboot. And it was during the world’s reboot at the tech to translate the Wachowskis’ sprawling SHINY turn of the millennium, around the time a particular universe more accurately into a videogame. -

BEFORE the PHILOSOPHY There Are Several Ways That We Might Explain the Location of the Matrix

ONE BEFORE THE 7 PHILOSOPHY UNDERSTANDING THE FILMS BEFORE THE PHILOSOPHY I’m really struggling here. I’m trying to keep up, but I’m losing the plot. There is way too much weird shit going on around here and nothing is going the way it is supposed to go. I mean, doors that go nowhere and everywhere, programs acting like humans, multiplying agents . Oh when, when will it end? – SparksE The Matrix films often left audiences more confused than they had bargained for. Some say that their confusion began with the very first film, and was compounded with each sequel. Others understood the big picture, but found themselves a bit perplexed concerning the details. It’s safe to say that no one understands the films completely – there are always deeper levels to consider. So before we explore the more philosophical aspects of the films, I hope to clarify some of the common points of confusion. But first, I strongly encourage you to watch all three films. There are spoilers ahead. The Matrix Dreamworld You mean this isn’t real? – Neo† The Matrix is essentially a computer-generated dreamworld. It is the illusion of a world that no longer exists – a world of human technology and culture as it was at the end of the twentieth century. This illusion is pumped into the brains of millions of people who, in reality, are lying fast asleep in slime-filled cocoons. To them this virtual world seems like real life. They go to work, watch their televisions, and pay their taxes, fully believing that they are physically doing these things, when in fact they are doing them “virtually” – within their own minds. -

Facing the Absurd Existentialism for Humans and Programs

TWELVE 150 FACING THE ABSURD EXISTENTIALISM FOR HUMANS AND PROGRAMS The Matrix cannot tell you who you are. – Trinity†† Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself. Such is the first principle of existentialism. – Jean-Paul Sartre FACING THE ABSURD Of Gods and Architects Søren Kierkegaard, whose existentialist philosophy of faith was discussed in the previous chapter, requested that just two words be engraved on his tombstone at his death: THE INDIVIDUAL. This gesture nicely summarizes the main thrust of the existentialist movement in philosophy – which both begins and ends with the individual. Existentialism focuses on the issues that arise for us as separate and distinct persons who are, in a very profound sense, alone in the world. Its emphasis is on personal responsibility – on taking responsibility for who you are, what you do, and the meanings that you give to the world around you. While Kierkegaard’s existentialism was largely inspired by his religious commit- ments, atheism was the guiding assumption for many existentialist writers, includ- ing Martin Heidegger, Albert Camus, and Jean-Paul Sartre. In Existentialism as a Humanism, the French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre explained how his philo- sophy was intimately tied to his atheism through the example of a paper-cutter. [H]ere is an object which has been made by an artisan whose inspiration came from a concept. He referred to the concept of what a paper-cutter is and likewise to a known method of production, which is part of the concept, something which by and large is a routine. Thus, the paper-cutter is at once an object produced in a certain way and, on the other hand, one having a specific use . -

Matrix Reloaded Explained

Matrix Reloaded Explained Matrix Reloaded Explained The Matrix Explained 1 The Matrix: Reloaded Explained.........................................................................................................................1 1.1 Contents...................................................................................................................................................1 2 Forward on disobedience.......................................................................................................................................3 3 Foundation of criticism..........................................................................................................................................5 4 The Architect..........................................................................................................................................................7 5 The rave scene......................................................................................................................................................11 6 The Oracle.............................................................................................................................................................13 7 Agent Smith..........................................................................................................................................................15 8 Story arc................................................................................................................................................................19 -

The Matrix Revolution, Part I

The Matrix Revolution, Part 1 by Ben Sibelman with an excerpt from The Matrix and excerpts from two versions of The Matrix Reloaded script, by Larry and Andy Wachowski (Bold text in the excerpts indicates added material. Strikeouts and ellipses indicate skipped material.) Sources The Matrix transcript: http://www.ix625.com/matrixscript.html The Matrix Reloaded draft script: http://www.imsdb.com/scripts/Matrix-Reloaded,-The.html The Matrix Reloaded shooting script: http://www.horrorlair.com/movies/scripts/matrixreloaded.pdf The Matrix, its sequels, and all related characters, plots, images, and concepts are the property of the Wachowski brothers, Warner Brothers, and/or Village Roadshow Pictures. Consequently, this script cannot be used for commercial gain. It is free for your use and may be copied and distributed at will. SCENE 1 Total blackness. NEO (V.O. from the end of The Matrix) I know you're out there. I can feel you now. Down into the black screen comes a single column of glowing green symbols. It is quickly joined by many others as the camera closes in. NEO (cont’d) I know that you're afraid. You're afraid of us. You're afraid of change. 19 of the columns terminate in the letters of “THE MATRIX REVOLUTION.” The camera passes through the U, which extends back into a canyon of smaller symbols with gaps in its walls. 1 NEO (cont’d) I don't know the future. I didn't come here to tell you how this is going to end. I came here to tell you how it's going to begin. -

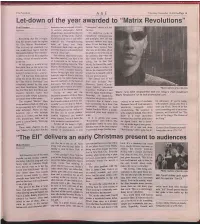

Let-Down of the Year Awarded to “Matrix Revolutions”

The Pendulum A & E Thursday, November 13, 2003 wPage 19 Let-down of the year awarded to “Matrix Revolutions” Sean Hennen humanity and no amount of tired- “cineophile” should still feel Reviewer ly endless philosophic babble the loss. about choice, love and destiny can An addictive cycle of reclaim the feeling of the original. metaphoric introspections Everything that has a begin It’s all mere lip service and unfor and gunfights isn’t all that ning has an end, reads the tagline tunately the writing/directing attracted viewers way back for “The Matrix: Revolutions.” team of Larry and Andy when. It was the story of a This is a very apt statement, but Wachowski think they can gloss fallible hero named Neo one would have hoped that the over this absence with intellectual who was as uncertain about filmmakers behind “Revolutions” overkill. They can’t. his ability to save the day as would have strived for a superior For viewers who haven’t seen the audience. Say what you ending, instead of merely an ade the other movies, you have a lot will about Keanu Reeves’ quate one. of homework to do before you acting, but in that first At this point, it is safe to say think about sitting down for “The movie, he forced the audi that each film in the series has Matrix: Revolutions.” The movie ence to learn to believe in become successively tired and - doesn’t even consider pausing him as his character learned though it is hard to say - unorigi before diving right back into the to believe in himself. -

Ghost Guerriero Zen

Ghost: guerriero zen e portavoce delle idee filosofiche dei Wachowski A discapito di quello che comunemente si possa pensare, Enter the Matrix, per la sua funzione propriamente integrativa alla trilogia, consiste in uno dei capitoli più importanti dell’universo Matrix, difatti molti degli aspetti affascinanti, tra i quali spicca la caratterizzazione di uno dei personaggi più misteriosi dell’intera vicenda, ossia Ghost, sono interamente ed elusivamente affidati a questo videogioco. Ghost il fantasma È ormai risaputo che i nomi assegnati a ciascun personaggio della saga, anche quelli più insignificanti, celano un significato più o meno recondito, e nel caso di Ghost diviene piuttosto facile da intuire. Difatti lo spettatore che non va oltre la visione di “The Matrix Reloaded” non ha la più pallida idea di chi possa essere, ed anche per quanto riguarda le vicende narrate in “Enter the Matrix” solitamente egli svolge un ruolo di “copertura” nei confronti di Niobe. Se si tiene conto, inoltre, che due delle scene di “Enter the Matrix” che ci forniscono importanti informazioni su questo personaggio, e cioè le quelle dell’incontro con Persephone e l’Oracolo, sono da considerarsi parallele e quindi precluse dalla trama principale, che invece prevede Niobe al suo posto, diviene palese come questo personaggio si manifesti esclusivamente come “fantasma”. Ghost quindi personaggio fantasma, in quanto è presente ed agisce, ma sempre nell’ombra. Nonostante ciò, la caratterizzazione del personaggio risulta tutt’altro che superficiale… Ghost guerriero zen Che Ghost si rifaccia all’antica disciplina zen è piuttosto chiaro, e la cosa la si può facilmente intuire osservando l’ambientazione del suo personale programma d’allenamento, che infatti riproduce il caratteristico “giardino di rocce” zen giapponese: 1 Ma questo suo “essere zen” va ben oltre… Centrale nell’insegnamento zen è l’importanza di una ferrea disciplina, necessaria per poter praticare una meditazione che porti all’illuminazione, considerata come il supremo stato della conoscenza e dell’esistenza. -

Nick Fury, Will Smith, and Other Black Authority Figures Breaking the Racial Contract in Popular Films of 2000-2015

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Spring 5-2017 Nick Fury, Will Smith, and Other Black Authority Figures Breaking the Racial Contract in Popular Films of 2000-2015 Solai N. Wyman University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Wyman, Solai N., "Nick Fury, Will Smith, and Other Black Authority Figures Breaking the Racial Contract in Popular Films of 2000-2015" (2017). Master's Theses. 292. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/292 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NICK FURY, WILL SMITH, AND OTHER BLACK AUTHORITY FIGURES BREAKING THE RACIAL CONTRACT IN POPULAR FILMS OF 2000-2015 by Solai N. Wyman A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School and the Department of Political Science, International Development, and International Affairs at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved: ________________________________________________ Dr. Allan McBride, Committee Chair Associate Professor, Political Science, International Development, and International Affairs ________________________________________________ Dr. Marek Steedman, Committee Member Associate Professor, Political Science, International Development, and International Affairs ________________________________________________ Dr. Joseph Weinberg, Committee Member Assistant Professor, Political Science, International Development, and International Affairs _______________________________________________ Dr. Edward Sayre Chair, Department of Political Science, International Development, and International Affairs ________________________________________________ Dr. -

The Matrix: Unloaded Revelations

CHRISTIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE P.O. Box 8500, Charlotte, NC 28271 Feature Article: DM820 THE MATRIX: UNLOADED REVELATIONS by Brian Godawa This article first appeared in the Christian Research Journal, volume 27, number 1 (2004). For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal go to: http://www.equip.org SYNOPSIS Everyone who has seen The Matrix trilogy knows that it presents a religious/philosophical worldview; what that worldview is, however, is a matter of debate. Some have argued it is Christian; some, Platonic (the philosophy of Plato); others, Gnostic (a Christian heresy); and still others, Buddhist. The films seem to use a combination of all of the above as metaphors for a postmodern worldview that deconstructs universal “savior” mythology into a Nietzschean “superman” philosophy in which one creates one’s own truth in a universe without God. In Nietzsche’s philosophy, our perceptions of reality are illusory (the theme in The Matrix) because they are part of the mechanistic determinism of nature (the theme in The Matrix: Reloaded). We must, therefore, create our own “new truth” through our human choices and beliefs (the theme in The Matrix: Revolutions). This worldview, however, is diametrically opposed to Christianity; hence, any similarities between themes or characters in The Matrix trilogy and orthodox Christianity are merely superficial. “To be truthful means using the customary metaphor — in moral terms: the obligation to lie according to a fixed convention, to lie herdlike in a style obligatory for all.”1 — Friedrich Nietzsche Mythologist Joseph Campbell sought to bring to light what he called the “monomyth,” the universal heroic journey common to all religions, which resides in the collective unconscious of humanity. -

Primary & Secondary Sources

Primary & Secondary Sources Brands & Products Agencies & Clients Media & Content Influencers & Licensees Organizations & Associations Government & Education Research & Data Multicultural Media Forecast 2019: Primary & Secondary Sources COPYRIGHT U.S. Multicultural Media Forecast 2019 Exclusive market research & strategic intelligence from PQ Media – Intelligent data for smarter business decisions In partnership with the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers Co-authored at PQM by: Patrick Quinn – President & CEO Leo Kivijarv, PhD – EVP & Research Director Editorial Support at AIMM by: Bill Duggan – Group Executive Vice President, ANA Claudine Waite – Director, Content Marketing, Committees & Conferences, ANA Carlos Santiago – President & Chief Strategist, Santiago Solutions Group Except by express prior written permission from PQ Media LLC or the Association of National Advertisers, no part of this work may be copied or publicly distributed, displayed or disseminated by any means of publication or communication now known or developed hereafter, including in or by any: (i) directory or compilation or other printed publication; (ii) information storage or retrieval system; (iii) electronic device, including any analog or digital visual or audiovisual device or product. PQ Media and the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers will protect and defend their copyright and all their other rights in this publication, including under the laws of copyright, misappropriation, trade secrets and unfair competition. All information and data contained in this report is obtained by PQ Media from sources that PQ Media believes to be accurate and reliable. However, errors and omissions in this report may result from human error and malfunctions in electronic conversion and transmission of textual and numeric data. -

Starlog Magazine

REVOLUTIO,UP On location with EE a LOONEY TUNES DOCTOR M CAT IN THE HAT A. m% TIMELINE # ^ HAUNTED TAKEN HULK MBm MANSION Fntpr if \/oii finro^ y SMALLVILLE sweetheart Kristin Kreuk us)TRU CALLING • TARZAN • JAKE 2.0 vw.starlog.com NUMBER 317 • DECEMBER 2003 • THE SCIENCE AbL &k\ INSIDE THIS ISSUE VACATION TERRORS Visiting Medieval France is no holiday for the Timeline team WIN A BET, ON A SET He does movie tricks at that, as they film The Cat in the Hat BUGS, ROBBY & JOE DANTE Toon royalty entertains SF's greatest with Looney Tunes: Back in Action START THE REVOLUTIONS Producer Joel Silver previews the future of The Matrix LIFE & DEATH IN ROBOTA Doug Chiang & Orson Scott Card envision a new universe ANIMATIONS OF JEDI Star Wars moves to Cartoon Network with Clone Wars GRIM GRINNING GHOSTS Abandon all hope, ye who enter The Haunted Mansion HOBBIT AT SEA This year, Billy Boyd takes part(s) in two epic adventures BRIGHT APE, BIG CITY Tarzan swings into New York's perilou jungle LANA LANG'S LOST LOVE It sizzles for Smallville's sweetheart Kristin Kreu TRU DESTINY The heroine relives yesterday to save tomorrow HEROIC UPGRADE Chris Gorham becomes an SF star as v. spy Jake 2.0 SCOTT BAKULA SPEAKS This starship captain hasn't given up his Enterprise DOUBLE DELIGHTS The Klimaszewski Sisters stand reve Trek twins HIS CYLON CHILDHOOD Noah Hathaway grew up on board Ba STARLOC: The science Fiction Universe is published monthly by STARLOG GROUP, INC., 475 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. -

The Matrix Online Storyline

Chapter 1.1 Introduction to the Matrix under the Truce. Chapter 1.2 Morpheus began a campaign of protest and sabotage to force the Machines to return Neo's body. Zion declared Morpheus' actions a threat to the Truce. Mysterious, hostile groups began to appear in the simulation: imposter Agents with red eyes, and groups of operatives with masks concealing their faces. Chapter 1.3 Morpheus was killed by the Assassin, an exiled disposal program in form of a fly- filled overcoat and porcelain mask. Niobe brought her own group of operatives into the Matrix, along with her new right-hand If You Can’t Beat Us by HostileIntention man, Anome, to bring Morpheus' killer to justice. Chapter 2.1 Niobe found out that it was the Merovingian who hired the Assassin. Operatives began to gather insecticide spray to fight him. Chapter 2.2 Insecticide-spraying flit gun weapons were assembled to fight the Assassin. He was found to move through phone lines, and reside on a garbage barge. The red-eyed Agents vandalized phone booths. The masked men were lying low. Chapter 2.3 An exiled program, the General, appeared with his commandos in a helicopter, with offers of help for the various organizations. The Assassin's power grew, but he was tracked down and killed. Chapter 3.1 Niobe sought revenge against the Merovingian for the death of Morpheus. The Machines were also working against the Merovingian. Mysterious hissing and creaking boxes appeared around the city. Chapter 3.2 The masked leader, Cryptos, appeared from the hissing boxes, preaching a return to sleep in the Machine pods.