Through the Looking Glass: the Matrix Franchise And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Enter the Matrix: Safely Interruptible Autonomous Systems Via Virtualization

Enter the Matrix: Safely Interruptible Autonomous Systems via Virtualization Mark O. Riedl Brent Harrison School of Interactive Computing Department of Computer Science Georgia Institute of Technology University of Kentucky [email protected] [email protected] Abstract • An autonomous system may have imperfect sensors and perceive the world incorrectly, causing it to perform the Autonomous systems that operate around humans will wrong behavior. likely always rely on kill switches that stop their exe- cution and allow them to be remote-controlled for the • An autonomous system may have imperfect actuators and safety of humans or to prevent damage to the system. It thus fail to achieve the intended effects even when it has is theoretically possible for an autonomous system with chosen the correct behavior. sufficient sensor and effector capability that learn on- • An autonomous system may be trained online meaning line using reinforcement learning to discover that the kill switch deprives it of long-term reward and thus it is learning as it is attempting to perform a task. Since learn to disable the switch or otherwise prevent a hu- learning will be incomplete, it may try to explore state- man operator from using the switch. This is referred to action spaces that result in dangerous situations. as the big red button problem. We present a technique Kill switches provide human operators with the final author- that prevents a reinforcement learning agent from learn- ing to disable the kill switch. We introduce an interrup- ity to interrupt an autonomous system and remote-control it tion process in which the agent’s sensors and effectors to safety. -

Thematic, Moral and Ethical Connections Between the Matrix and Inception

Thematic, Moral and Ethical Connections Between the Matrix and Inception. Modern Day science and technology has been crucial in the development of the modern film industry. In the past, directors have been confined by unwieldy, primitive cameras and the most basic of special effects. The contemporary possibilities now available has enabled modern film to become more dynamic and versatile, whilst also being able to better capture the performance of actors, and better display scenes and settings using special effects. As the prevalence of technology in society increases, film makers have used their medium to express thematic, moral and ethical concerns of technology in human life. The films I will be looking at: The Matrix, directed by the Wachowskis, and Inception, directed by Christopher Nolan, both explore strong themes of technology. The theme of technology is expanded upon as the directors of both films explore the use of augmented reality and its effects on the human condition. Through the use of camera angles, costuming and lighting, the Witkowski brothers represent the idea that technology is dangerous. During the sequence where neo is unplugged from the Matrix, the directors have cleverly combines lighting, visual and special effects to craft an ominous and unpleasant setting in which the technology is present. Upon Neo’s confrontation with the spider drone, the use of camera angles to establishes the dominance of technology. The low-angle shot of the drone places the viewer in a subordinate position, making the drone appear powerful. The dingy lighting and poor mis-en-scene in the set further reinforces the idea that technology is dangerous. -

Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES the ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’S Done with ‘Drag Race’

Drag Syndrome Barred From Tanglefoot: Discrimination or Protection? A Guide to the Upcoming Democratic Presidential Kentucky Marriage Battle LGBTQ Debates Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES The ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’s Done with ‘Drag Race’ PRIDESOURCE.COM SEPT.SEPT. 12, 12, 2019 2019 | | VOL. VOL. 2737 2737 | FREE New Location The Henry • Dearborn 300 Town Center Drive FREE PARKING Great Prizes! Including 5 Weekend Join Us For An Afternoon Celebration with Getaways Equality-Minded Businesses and Services Free Brunch Sunday, Oct. 13 Over 90 Equality Vendors Complimentary Continental Brunch Begins 11 a.m. Expo Open Noon to 4 p.m. • Free Parking Fashion Show 1:30 p.m. 2019 Sponsors 300 Town Center Drive, Dearborn, Michigan Party Rentals B. Ella Bridal $5 Advance / $10 at door Family Group Rates Call 734-293-7200 x. 101 email: [email protected] Tickets Available at: MiLGBTWedding.com VOL. 2737 • SEPT. 12 2019 ISSUE 1123 PRIDE SOURCE MEDIA GROUP 20222 Farmington Rd., Livonia, Michigan 48152 Phone 734.293.7200 PUBLISHERS Susan Horowitz & Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL 22 Editor in Chief Susan Horowitz, 734.293.7200 x 102 [email protected] Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi, 734.293.7200 x 106 [email protected] News & Feature Editor Eve Kucharski, 734.293.7200 x 105 [email protected] 12 10 News & Feature Writers Michelle Brown, Ellen Knoppow, Jason A. Michael, Drew Howard, Jonathan Thurston CREATIVE Webmaster & MIS Director Kevin Bryant, [email protected] Columnists Charles Alexander, -

What's in a Name? the Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 9-2008 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2008). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Math Horizons 16.1, 18-21. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/12 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In lieu of an abstract, here is the article's first paragraph: In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix to illustrate the nature of evidence and how it shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician, I usually field questions elatedr to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Disciplines Mathematics Comments Article copyright 2008 by Math Horizons. -

The Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 2012 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2012). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Mathematics in Popular Culture: Essays on Appearances in Film, Fiction, Games, Television and Other Media , 44-54. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/18 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix (1999) to illustrate how evidence shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician and self-confessed science fiction fan, I usually field questionselated r to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Of course, there are many possible explanations for this, each of which probably contributed a little to the naming decision. -

Document 273 5-5-2014 – Download

Case 2:07-cv-00552-DB-EJF Document 273 Filed 05/05/14 Page 1 of 46 PROSE 1 SOPHIA STEWART P.O. BOX 31725 2 Las Vegasl NV 89173 3 702-501-5900 (PH) 4 ... IN PROPRIA PERSONA v: ---;;:\-CQ\( 5 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT \l~YU I I "' 6 FOR THE DISTRICT OF UTAH 7 SOPHIA STEWART, HON. EVELYN J. FURSE 8 Plaintiff, v. HON. DEE BENSON 9 MICHAEL STOLLER, GARY BROWN, Case No.: 2:07CV552 DB-EJF 10 DEAN WEBB, AND JONATHAN 11 LUBELL OBJECTION TO COURT DENIAL Defendants. TO AWARD DAMAGES AGAINST 12 DEFENDANT LUBELL AND 13 DEMAND FOR EXPEDITED AWARD 14 15 16 COMES NOW1 PLAINTIFF SOPHIA STEWART1 bringing forth the Objection To the 17 Court's Denial To Award Damages Against All Defendants And Demand For 18 Expedited Award of Damages in the amount of One Billion Three Hundred and 19 Sixty Seven Million $1,367,000,000.00 dollars for The Matrix Trilogy damages and 20 Three point five Billion $3,580,000,000.00 dollars in damages for the Terminator 21 Franchise Series. 22 23 Plaintiff brings forth this objection against the court for violating the 24 Plaintiff's constitutional Sixth and fourth amendments "Due Process and Equal 25 Protection" rights and obstructing her from a jury trial and the ability to face the 26 defendants in court for more than 6 years while Jonathan Lubell was deceased, 27 thus constituting a violation of racial discrimination and fraud. Racial 28 discrimination by concerted action is a federal offense under 18 U.S.C. -

3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality

3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality BY ANDREAS SUDMANN I’ve watched you, Neo. You do not use a computer like a tool. You use it like it was part of yourself. —Morpheus in The Matrix Digital computers, these universal machines, are everywhere; virtually ubiquitous, they surround us, and they do so all the time. They are even inside our bodies. They have become so familiar and so deeply connected to us that we no longer seem to be aware of their presence (apart from moments of interruption, dysfunction—or, in short, events). Without a doubt, computers have become crucial actants in determining our situation. But even when we pay conscious attention to them, we necessarily overlook the procedural (and temporal) operations most central to computation, as these take place at speeds we cannot cognitively capture. How, then, can we describe the affective and temporal experience of digital media, whose algorithmic processes elude conscious thought and yet form the (im)material conditions of much of our life today? In order to address this question, this chapter examines several examples of digital media works (films, games) that can serve as central mediators of the shift to a properly post-cinematic regime, focusing particularly on the aesthetic dimensions of the popular and transmedial “bullet time” effect. Looking primarily at the first Matrix film | 1 3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality (1999), as well as digital games like the Max Payne series (2001; 2003; 2012), I seek to explore how the use of bullet time serves to highlight the medial transformation of temporality and affect that takes place with the advent of the digital—how it establishes an alternative configuration of perception and agency, perhaps unprecedented in the cinematic age that was dominated by what Deleuze has called the “movement-image.”[1] 1. -

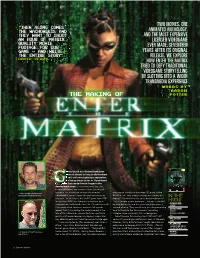

The Making of Enter the Matrix

TWO MOVIES. ONE “THEN ALONG COMES THE WACHOWSKIS AND ANIMATED ANTHOLOGY. THEY WANT TO SHOOT AND THE MOST EXPENSIVE AN HOUR OF MATRIX LICENSED VIDEOGAME QUALITY MOVIE FOOTAGE FOR OUR EVER MADE. SEVENTEEN GAME – AND WRITE YEARS AFTER ITS ORIGINAL THE ENTIRE STORY” RELEASE, WE EXPLORE DAVID PERRY HOW ENTER THE MATRIX TRIED TO DEFY TRADITIONAL VIDEOGAME STORYTELLING BY SLOTTING INTO A WIDER TRANSMEDIA EXPERIENCE Words by Aaron THE MAKING OF Potter ames based on a licence have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It’s an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with » Shiny Entertainment founder and making a fun, interactive version of a beloved working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called former game director David Perry. Hollywood IP weren’t given the time necessary to Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the IN THE succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 project.” David chalks this up as being high on his for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a “list of terrible career decisions”, though it wouldn’t KNOW single person and helped cause the US industry crash. be long before he and his team would be given a PUBLISHER: ATARI After every crash, however, comes a full system second chance. They could even use this pioneering DEVELOPER : reboot. And it was during the world’s reboot at the tech to translate the Wachowskis’ sprawling SHINY turn of the millennium, around the time a particular universe more accurately into a videogame. -

Instructables.Com/Id/How-To-Enter-The-Ghetto-Matrix-DIY-Bullet-Time/ License: Public Domain Dedication (Pd)

Home Sign Up! Explore Community Submit All Art Craft Food Games Green Home Kids Life Music Offbeat Outdoors Pets Photo Ride Science Tech How to Enter the Ghetto Matrix (DIY Bullet Time) by fi5e on December 19, 2007 Table of Contents License: Public Domain Dedication (pd) . 2 Intro: How to Enter the Ghetto Matrix (DIY Bullet Time) . 2 step 1: Tools & Materials . 4 step 2: Dimension . 8 step 3: Cut Wood . 9 step 4: Drill Holes . 10 step 5: Stand Connections . 11 step 6: Shutter Cable Hack . 13 step 7: the Control Box . 15 step 8: Setting Up the Rig . 20 step 9: Connecting All the Cameras . 22 step 10: Pick Your Spot! . 23 step 11: Ghetto Matrix Operations Quick-Start Guide . 24 step 12: Act a Fool Son! . 30 step 13: Post Production . 40 step 14: Fin . 42 Related Instructables . 43 Advertisements . 43 Comments . 43 http://www.instructables.com/id/How-to-Enter-the-Ghetto-Matrix-DIY-Bullet-Time/ License: Public Domain Dedication (pd) Intro: How to Enter the Ghetto Matrix (DIY Bullet Time) The following is a tutorial on how to build your own cheap, portable and hood-style bullet time camera rig on the cheap and the fly. This rig was designed by the Graffiti Research Lab and director Dan the Man to use in a hip-hop music video for underground rappers Styles P , AZ and the legendary Large Professor (spinning below). Just another chapter in the GRL's continuing mission to make open source the sixth element of hip-hop. Peep the vid at the resolution of the proletariat (below): Or see how the higher-res live here . -

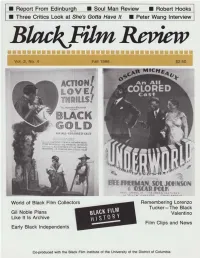

Report from Edinbur H • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview

Report From Edinbur h • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview World of Black Film Collectors Remembering Lorenzo Tucker- The Black. Gil Noble Plans Valentino Like It Is Archive Film Clips and News Early Black Independents Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Vol. 2, No. 4/Fa111986 'Peter Wang Breaks Cultural Barriers Black Film Review by Pat Aufderheide 10 SSt., NW An Interview with the director of A Great Wall p. 6 Washington, DC 20001 (202) 745-0455 Remembering lorenzo Tucker Editor and Publisher by Roy Campanella, II David Nicholson A personal reminiscence of one of the earliest stars of black film. ... p. 9 Consulting Editor Quick Takes From Edinburgh Tony Gittens by Clyde Taylor (Black Film Institute) Filmmakers debated an and aesthetics at the Edinburgh Festival p. 10 Associate EditorI Film Critic Anhur Johnson Film as a Force for Social Change Associate Editors by Charles Burnett Pat Aufderheide; Keith Boseman; Excerpts from a paper delivered at Edinburgh p. 12 Mark A. Reid; Saundra Sharp; A. Jacquie Taliaferro; Clyde Taylor Culture of Resistance Contributing Editors Excerpts from a paper p. 14 Bill Alexander; Carroll Parrott Special Section: Black Film History Blue; Roy Campanella, II; Darcy Collector's Dreams Demarco; Theresa furd; Karen by Saundra Sharp Jaehne; Phyllis Klotman; Paula Black film collectors seek to reclaim pieces of lost heritage p. 16 Matabane; Spencer Moon; An drew Szanton; Stan West. With a repon on effons to establish the Like It Is archive p. -

Matrix : from Representation to Simulation and Beyond

Lakehead University Knowledge Commons,http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca Electronic Theses and Dissertations Retrospective theses 2006 Matrix : from representation to simulation and beyond Bryx, Adam http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/3345 Downloaded from Lakehead University, KnowledgeCommons The Matrix: From Representation to Simulation and Beyond A thesis submitted to the Department of English Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English By Adam Bryx May 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliothèque et 1 ^1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-21530-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-21530-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse.