From Superman to Brahman: the Religious Shift of the Matrix Mythology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Thematic, Moral and Ethical Connections Between the Matrix and Inception

Thematic, Moral and Ethical Connections Between the Matrix and Inception. Modern Day science and technology has been crucial in the development of the modern film industry. In the past, directors have been confined by unwieldy, primitive cameras and the most basic of special effects. The contemporary possibilities now available has enabled modern film to become more dynamic and versatile, whilst also being able to better capture the performance of actors, and better display scenes and settings using special effects. As the prevalence of technology in society increases, film makers have used their medium to express thematic, moral and ethical concerns of technology in human life. The films I will be looking at: The Matrix, directed by the Wachowskis, and Inception, directed by Christopher Nolan, both explore strong themes of technology. The theme of technology is expanded upon as the directors of both films explore the use of augmented reality and its effects on the human condition. Through the use of camera angles, costuming and lighting, the Witkowski brothers represent the idea that technology is dangerous. During the sequence where neo is unplugged from the Matrix, the directors have cleverly combines lighting, visual and special effects to craft an ominous and unpleasant setting in which the technology is present. Upon Neo’s confrontation with the spider drone, the use of camera angles to establishes the dominance of technology. The low-angle shot of the drone places the viewer in a subordinate position, making the drone appear powerful. The dingy lighting and poor mis-en-scene in the set further reinforces the idea that technology is dangerous. -

What's in a Name? the Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 9-2008 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2008). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Math Horizons 16.1, 18-21. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/12 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In lieu of an abstract, here is the article's first paragraph: In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix to illustrate the nature of evidence and how it shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician, I usually field questions elatedr to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Disciplines Mathematics Comments Article copyright 2008 by Math Horizons. -

The Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 2012 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2012). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Mathematics in Popular Culture: Essays on Appearances in Film, Fiction, Games, Television and Other Media , 44-54. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/18 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix (1999) to illustrate how evidence shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician and self-confessed science fiction fan, I usually field questionselated r to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Of course, there are many possible explanations for this, each of which probably contributed a little to the naming decision. -

Christianity, Buddhism & Baudrillard in the Matrix Films and Popular Culture

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS College of Liberal Arts & Sciences 2010 The Desert of the Real: Christianity, Buddhism & Baudrillard in The Matrix Films and Popular Culture James F. McGrath Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation James F. McGrath. "The Desert of the Real: Christianity, Buddhism & Baudrillard in The Matrix Films and Popular Culture" Visions of the Human in Science Fiction and Cyberpunk. Ed. Marcus Leaning & Birgit Pretzsch. Oxford, UK: Inter-Disciplinary Press, 2010. 161-172. Available from: digitalcommons.butler.edu/ facsch_papers/556/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Edited by Marcus Leaning & Birgit Pretzsch The Desert of the Real: Christianity, Buddhism & Baudrillard in The Matrix Films and Popular Culture James F. McGrath Abstract The movie The Matrix and its sequels draw explicitly on imagery from a number of sources, including in particular Buddhism, Christianity, and the writings of Jean Baudrillard. A perspective is offered on the perennial philosophical question ‘What is real?’, using language and symbols drawn from three seemingly incompatible world views. In doing so, these movies provide us with an insight into the way popular culture makes eclectic use of various streams of thought to fashion a new reality that is not unrelated to, and yet is nonetheless distinct from, its religious and philosophical undercurrents and underpinnings. -

The World's Religions After September 11

The World’s Religions after September 11 This page intentionally left blank The World’s Religions after September 11 Volume 1 Religion, War, and Peace EDITED BY ARVIND SHARMA PRAEGER PERSPECTIVES Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The world’s religions after September 11 / edited by Arvind Sharma. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-275-99621-5 (set : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-275-99623-9 (vol. 1 : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-275-99625-3 (vol. 2 : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-275-99627-7 (vol. 3 : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-275-99629-1 (vol. 4 : alk. paper) 1. Religions. 2. War—Religious aspects. 3. Human rights—Religious aspects. 4. Religions—Rela- tions. 5. Spirituality. I. Sharma, Arvind. BL87.W66 2009 200—dc22 2008018572 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2009 by Arvind Sharma All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2008018572 ISBN: 978-0-275-99621-5 (set) 978-0-275-99623-9 (vol. 1) 978-0-275-99625-3 (vol. 2) 978-0-275-99627-7 (vol. 3) 978-0-275-99629-1 (vol. 4) First published in 2009 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48-1984). -

Full Complaint

Case 1:18-cv-01612-CKK Document 11 Filed 11/17/18 Page 1 of 602 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ESTATE OF ROBERT P. HARTWICK, § HALEY RUSSELL, HANNAH § HARTWICK, LINDA K. HARTWICK, § ROBERT A. HARTWICK, SHARON § SCHINETHA STALLWORTH, § ANDREW JOHN LENZ, ARAGORN § THOR WOLD, CATHERINE S. WOLD, § CORY ROBERT HOWARD, DALE M. § HINKLEY, MARK HOWARD BEYERS, § DENISE BEYERS, EARL ANTHONY § MCCRACKEN, JASON THOMAS § WOODLIFF, JIMMY OWEKA OCHAN, § JOHN WILLIAM FUHRMAN, JOSHUA § CRUTCHER, LARRY CRUTCHER, § JOSHUA MITCHELL ROUNTREE, § LEIGH ROUNTREE, KADE L. § PLAINTIFFS’ HINKHOUSE, RICHARD HINKHOUSE, § SECOND AMENDED SUSAN HINKHOUSE, BRANDON § COMPLAINT HINKHOUSE, CHAD HINKHOUSE, § LISA HILL BAZAN, LATHAN HILL, § LAURENCE HILL, CATHLEEN HOLY, § Case No.: 1:18-cv-01612-CKK EDWARD PULIDO, KAREN PULIDO, § K.P., A MINOR CHILD, MANUEL § Hon. Colleen Kollar-Kotelly PULIDO, ANGELITA PULIDO § RIVERA, MANUEL “MANNIE” § PULIDO, YADIRA HOLMES, § MATTHEW WALKER GOWIN, § AMANDA LYNN GOWIN, SHAUN D. § GARRY, S.D., A MINOR CHILD, SUSAN § GARRY, ROBERT GARRY, PATRICK § GARRY, MEGHAN GARRY, BRIDGET § GARRY, GILBERT MATTHEW § BOYNTON, SOFIA T. BOYNTON, § BRIAN MICHAEL YORK, JESSE D. § CORTRIGHT, JOSEPH CORTRIGHT, § DIANA HOTALING, HANNA § CORTRIGHT, MICHAELA § CORTRIGHT, LEONDRAE DEMORRIS § RICE, ESTATE OF NICHOLAS § WILLIAM BAART BLOEM, ALCIDES § ALEXANDER BLOEM, DEBRA LEIGH § BLOEM, ALCIDES NICHOLAS § BLOEM, JR., VICTORIA LETHA § Case 1:18-cv-01612-CKK Document 11 Filed 11/17/18 Page 2 of 602 BLOEM, FLORENCE ELIZABETH § BLOEM, CATHERINE GRACE § BLOEM, SARA ANTONIA BLOEM, § RACHEL GABRIELA BLOEM, S.R.B., A § MINOR CHILD, CHRISTINA JEWEL § CHARLSON, JULIANA JOY SMITH, § RANDALL JOSEPH BENNETT, II, § STACEY DARRELL RICE, BRENT § JASON WALKER, LELAND WALKER, § SUSAN WALKER, BENJAMIN § WALKER, KYLE WALKER, GARY § WHITE, VANESSA WHITE, ROYETTA § WHITE, A.W., A MINOR CHILD, § CHRISTOPHER F. -

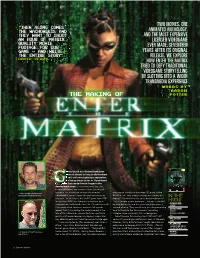

The Making of Enter the Matrix

TWO MOVIES. ONE “THEN ALONG COMES THE WACHOWSKIS AND ANIMATED ANTHOLOGY. THEY WANT TO SHOOT AND THE MOST EXPENSIVE AN HOUR OF MATRIX LICENSED VIDEOGAME QUALITY MOVIE FOOTAGE FOR OUR EVER MADE. SEVENTEEN GAME – AND WRITE YEARS AFTER ITS ORIGINAL THE ENTIRE STORY” RELEASE, WE EXPLORE DAVID PERRY HOW ENTER THE MATRIX TRIED TO DEFY TRADITIONAL VIDEOGAME STORYTELLING BY SLOTTING INTO A WIDER TRANSMEDIA EXPERIENCE Words by Aaron THE MAKING OF Potter ames based on a licence have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It’s an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with » Shiny Entertainment founder and making a fun, interactive version of a beloved working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called former game director David Perry. Hollywood IP weren’t given the time necessary to Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the IN THE succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 project.” David chalks this up as being high on his for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a “list of terrible career decisions”, though it wouldn’t KNOW single person and helped cause the US industry crash. be long before he and his team would be given a PUBLISHER: ATARI After every crash, however, comes a full system second chance. They could even use this pioneering DEVELOPER : reboot. And it was during the world’s reboot at the tech to translate the Wachowskis’ sprawling SHINY turn of the millennium, around the time a particular universe more accurately into a videogame. -

Matrix : from Representation to Simulation and Beyond

Lakehead University Knowledge Commons,http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca Electronic Theses and Dissertations Retrospective theses 2006 Matrix : from representation to simulation and beyond Bryx, Adam http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/3345 Downloaded from Lakehead University, KnowledgeCommons The Matrix: From Representation to Simulation and Beyond A thesis submitted to the Department of English Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English By Adam Bryx May 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliothèque et 1 ^1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-21530-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-21530-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. -

BEFORE the PHILOSOPHY There Are Several Ways That We Might Explain the Location of the Matrix

ONE BEFORE THE 7 PHILOSOPHY UNDERSTANDING THE FILMS BEFORE THE PHILOSOPHY I’m really struggling here. I’m trying to keep up, but I’m losing the plot. There is way too much weird shit going on around here and nothing is going the way it is supposed to go. I mean, doors that go nowhere and everywhere, programs acting like humans, multiplying agents . Oh when, when will it end? – SparksE The Matrix films often left audiences more confused than they had bargained for. Some say that their confusion began with the very first film, and was compounded with each sequel. Others understood the big picture, but found themselves a bit perplexed concerning the details. It’s safe to say that no one understands the films completely – there are always deeper levels to consider. So before we explore the more philosophical aspects of the films, I hope to clarify some of the common points of confusion. But first, I strongly encourage you to watch all three films. There are spoilers ahead. The Matrix Dreamworld You mean this isn’t real? – Neo† The Matrix is essentially a computer-generated dreamworld. It is the illusion of a world that no longer exists – a world of human technology and culture as it was at the end of the twentieth century. This illusion is pumped into the brains of millions of people who, in reality, are lying fast asleep in slime-filled cocoons. To them this virtual world seems like real life. They go to work, watch their televisions, and pay their taxes, fully believing that they are physically doing these things, when in fact they are doing them “virtually” – within their own minds. -

Facing the Absurd Existentialism for Humans and Programs

TWELVE 150 FACING THE ABSURD EXISTENTIALISM FOR HUMANS AND PROGRAMS The Matrix cannot tell you who you are. – Trinity†† Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself. Such is the first principle of existentialism. – Jean-Paul Sartre FACING THE ABSURD Of Gods and Architects Søren Kierkegaard, whose existentialist philosophy of faith was discussed in the previous chapter, requested that just two words be engraved on his tombstone at his death: THE INDIVIDUAL. This gesture nicely summarizes the main thrust of the existentialist movement in philosophy – which both begins and ends with the individual. Existentialism focuses on the issues that arise for us as separate and distinct persons who are, in a very profound sense, alone in the world. Its emphasis is on personal responsibility – on taking responsibility for who you are, what you do, and the meanings that you give to the world around you. While Kierkegaard’s existentialism was largely inspired by his religious commit- ments, atheism was the guiding assumption for many existentialist writers, includ- ing Martin Heidegger, Albert Camus, and Jean-Paul Sartre. In Existentialism as a Humanism, the French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre explained how his philo- sophy was intimately tied to his atheism through the example of a paper-cutter. [H]ere is an object which has been made by an artisan whose inspiration came from a concept. He referred to the concept of what a paper-cutter is and likewise to a known method of production, which is part of the concept, something which by and large is a routine. Thus, the paper-cutter is at once an object produced in a certain way and, on the other hand, one having a specific use . -

The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 9 Issue 2 October 2005 Article 7 October 2005 He is the One: The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah Mark D. Stucky [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Stucky, Mark D. (2005) "He is the One: The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 9 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol9/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. He is the One: The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah Abstract Many films have used Christ figures to enrich their stories. In The Matrix trilogy, however, the Christ figure motif goes beyond superficial plot enhancements and forms the fundamental core of the three-part story. Neo's messianic growth (in self-awareness and power) and his eventual bringing of peace and salvation to humanity form the essential plot of the trilogy. Without the messianic imagery, there could still be a story about the human struggle in the Matrix, of course, but it would be a radically different story than that presented on the screen. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol9/iss2/7 Stucky: He is the One Introduction The Matrix1 was a firepower-fueled film that spin-kicked filmmaking and popular culture.