Chapter 8. Gems and Man: a Brief History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tiger's Eye Is Not a Pseudomorph Glenn Morita in the Early 1800’S, Mineralogists Recognized That Tiger’S Eye Was a Fibrous Variey of Quartz

Minutes of the 05/20/03 Westside Board Meeting VP Stu Earnst opened the meeting at 7:31pm. Treasurer’s report read by Kathy Earnst. Minutes approved as published in the newsletter. Old business: Lease on Walker valley discussed. The expiration notice was sent but we are not sure who it went to. We do not see any obstacle to renewal as communication between the council and DNR are open and ongoing. Special thanks, to DNR representative, Laurie Bergvall and DNR staff for their time and effort in hearing our concerns and working towards mutually beneficial solutions on the Walker Valley issues. Sign production is on hold until the sign committee decides where and what the signs will say. We have decided that they will not be on the gate but separate from it. There will be a gate going up at Walker Valley but we will have access to that lock and it will probably be a combo type of thing that we can easily give to other rockhound clubs going there. Talked about the possibility of posing the combo on website but that will depend on the type of gate they put up and what ends up being possible with the mechanics of that gate. New business: Thank you from Bob Pattie and Ed Lehman to Bruce Himko and AAA Printing for donation of the paper. Thank you to Danny Vandenberg for providing sample Walker Valley Material to DNR to show the value of the material we are trying to preserve and enjoy. Bob Pattie is pursuing with the retrieval of our state seized funds through the unclaimed property process. -

Red Glass for the Pharaoh Thilo Rehren

. ARCHAEOLOGY INTERNATIONAL HildO<heim, Genn•ny) '' excmting '� Red glass for the Pharaoh industrial estate dating to the foundatio period of the new city, including the larg-� I Thilo Rehren est known bronze foundries of antiquity,1 Glass in ancient Egypt appears to have been used as a substitute military workshops supplying and main for precious stones that were not available in the country. Here taining the pharaoh's chariotry including the process of glass manufacture is traced through the examina stables for hundreds of horses, and the only known production site for glass in tion of the fr agmentaryremains of ceramic reaction vessels and Bronze Age Egypt and Mesopotamia. The crucibles used in the production of small glass ingots. excavations date back to the 1980s, but only in the past couple of years have we been able to identify the glassmaking evi n archaeological terms, glass is a these precious materials, and ancient Egypt dence, although much of it had been exca relatively young material that was is no exception to this rule. It was famous vated many years previously. Why this invented much later than pottery or for its riches in gold, but had no silver ores; delay? Because we didn't know how to rec Imetals; only from the beginning of it produced amethyst, carnelian and tur ognize glassmaking: there being no prece the Late Bronze Age onwards do we quoise, but not lapis lazuli, amber or ob dent or template to follow when looking have good evidence for its intentional and sidian. Should the country's rulers there for Bronze Age glassmaking, and the evi routine production. -

AMETHYSTINE CHALCEDONY by James E

NOTES ANDa NEW TECHNIQUES AMETHYSTINE CHALCEDONY By James E. Shigley and John I. Koivula A new amethystine chalcedony has been discovered in that this is one of the few reported occurrences Arizona. The material, marketed under the trade name where an amethyst-like, or amethystine, chalced- "Damsonite," is excellent for both jewelry and carv- ony has been found in quantities of gemological ings. The authors describe thegemological properties of importance (see Frondel, 1962). Popular gem this new type of chalcedony, and report the effects of hunters' guides, such as MacFall (1975) and heat treatment on it. Although this purple material is Anthony et al. (19821, describe minor occurrences apparently b.new color type of chalcedony, it has the same gemological properties as the other better-known in Arizona of banded purple agate, but give no types. It corresponds to a microcrystalline form of ame- indication of deposits of massive purple chalced- thyst which, when heat treated at approximately ony similar to that described here. This article 500°C becomes yellowish orange, as does some briefly summarizes the occurrence, gemological single-crystal amethyst. properties, and reaction to heat treatment of this material. LOCALITY AND OCCURRENCE The purple chalcedony described here has been Chalcedony is a microcrystalline form of quartz found at a single undisclosed locality in central that occurs in a wide variety of patterns and colors. Arizona. It was first noted as detrital fragments in Numerous types of chalcedony, such as chryso- the bed of a dry wash that cuts through a series of prase, onyx, carnelian, agate, and others, have been sedimentary rocks. -

Origin of Fibrosity and Banding in Agates from Flood Basalts: American Journal of Science, V

Agates: a literature review and Electron Backscatter Diffraction study of Lake Superior agates Timothy J. Beaster Senior Integrative Exercise March 9, 2005 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Bachelor of Arts degree from Carleton College, Northfield, Minnesota. 2 Table of Contents AGATES: A LITERATURE REVEW………………………………………...……..3 Introduction………………....………………………………………………….4 Structural and compositional description of agates………………..………..6 Some problems concerning agate genesis………………………..…………..11 Silica Sources…………………………………………..………………11 Method of Deposition………………………………………………….13 Temperature of Formation…………………………………………….16 Age of Agates…………………………………………………………..17 LAKE SUPERIOR AGATES: AN ELECTRON BACKSCATTER DIFFRACTION (EBSD) ANALYSIS …………………………………………………………………..19 Abstract………………………………………………………………………...19 Introduction……………………………………………………………………19 Geologic setting………………………………………………………………...20 Methods……………………………………………………...…………………20 Results………………………………………………………….………………22 Discussion………………………………………………………………………26 Conclusions………………………………………………….…………………26 Acknowledgments……………………………………………………..………………28 References………………………………………………………………..……………28 3 Agates: a literature review and Electron Backscatter Diffraction study of Lake Superior agates Timothy J. Beaster Carleton College Senior Integrative Exercise March 9, 2005 Advisor: Cam Davidson 4 AGATES: A LITERATURE REVEW Introduction Agates, valued as semiprecious gemstones for their colorful, intricate banding, (Fig.1) are microcrystalline quartz nodules found in veins and cavities -

Reflective Index Reference Chart

REFLECTIVE INDEX REFERENCE CHART FOR PRESIDIUM DUO TESTER (PDT) Reflective Index Refractive Reflective Index Refractive Reflective Index Refractive Gemstone on PDT/PRM Index Gemstone on PDT/PRM Index Gemstone on PDT/PRM Index Fluorite 16 - 18 1.434 - 1.434 Emerald 26 - 29 1.580 - 1.580 Corundum 34 - 43 1.762 - 1.770 Opal 17 - 19 1.450 - 1.450 Verdite 26 - 29 1.580 - 1.580 Idocrase 35 - 39 1.713 - 1.718 ? Glass 17 - 54 1.440 - 1.900 Brazilianite 27 - 32 1.602 - 1.621 Spinel 36 - 39 1.718 - 1.718 How does your Presidium tester Plastic 18 - 38 1.460 - 1.700 Rhodochrosite 27 - 48 1.597 - 1.817 TL Grossularite Garnet 36 - 40 1.720 - 1.720 Sodalite 19 - 21 1.483 - 1.483 Actinolite 28 - 33 1.614 - 1.642 Kyanite 36 - 41 1.716 - 1.731 work to get R.I. values? Lapis-lazuli 20 - 23 1.500 - 1.500 Nephrite 28 - 33 1.606 - 1.632 Rhodonite 37 - 41 1.730 - 1.740 Reflective indices developed by Presidium can Moldavite 20 - 23 1.500 - 1.500 Turquoise 28 - 34 1.610 - 1.650 TP Grossularite Garnet (Hessonite) 37 - 41 1.740 - 1.740 be matched in this table to the corresponding Obsidian 20 - 23 1.500 - 1.500 Topaz (Blue, White) 29 - 32 1.619 - 1.627 Chrysoberyl (Alexandrite) 38 - 42 1.746 - 1.755 common Refractive Index values to get the Calcite 20 - 35 1.486 - 1.658 Danburite 29 - 33 1.630 - 1.636 Pyrope Garnet 38 - 42 1.746 - 1.746 R.I value of the gemstone. -

Healing Gemstones for Everyday Use

GUIDE TO THE WORLD’S TOP 20 MOST EFFECTIVE HEALING GEMSTONES FOR EVERYDAY USE BY ISABELLE MORTON Guide to the World’s Top 20 Most Effective Healing Gemstones for Everyday Use Copyright © 2019 by Isabelle Morton Photography by Ryan Morton, Isabelle Morton Cover photo by Jeff Skeirik All rights reserved. Published by The Gemstone Therapy Institute P.O. Box 4065 Manchester, Connecticut 06045 U.S.A. www.GemstoneTherapyInstitute.org IMPORTANT NOTICE This book is designed to provide information for purposes of reference and guidance and to accompany, not replace, the services of a qualified health care practitioner or physician. It is not the intent of the author or publisher to prescribe any substance or method to cure, mitigate, treat, or prevent any disease. In the event that you use this information with or without seeking medical attention, the author and publisher shall not be liable or otherwise responsible for any loss, damage, or injury directly or indirectly caused by or arising out of the information contained herein. CONTENTS Gemstones for Physical Healing Light Green Aventurine 5 Dark Green Aventurine 11 Malachite 17 Tree Agate 23 Gemstones for Emotional Healing Rhodonite 30 Morganite 36 Pink Chalcedony 43 Rose Quartz 49 Gemstones for Healing Memory, Patterns, & Habits Opalite 56 Leopardskin Jasper 62 Golden Beryl 68 Rhodocrosite 74 Gemstones for Healing the Mental Body Sodalite 81 Blue Lace Agate 87 Lapis Lazuli 93 Lavender Quartz 99 Gemstones to Nourish Your Spirit Amethyst 106 Clear Quartz / Frosted Quartz 112 Mother of Pearl 118 Gemstones For Physical Healing LIGHT GREEN AVENTURINE DARK GREEN AVENTURINE MALACHITE TREE AGATE https://GemstoneTherapyInstitute.org LIGHT GREEN AVENTURINE 5 Copyright © 2019 Isabelle Morton. -

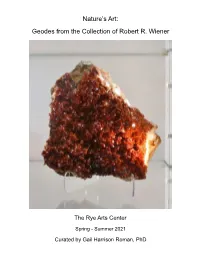

Nature's Art: Geodes from the Collection of Robert R. Wiener

Nature’s Art: Geodes from the Collection of Robert R. Wiener The Rye Arts Center Spring - Summer 2021 Curated by Gail Harrison Roman, PhD A Tribute to Robert R. Wiener The Rye Arts Center extends its gratitude and love to Bob Wiener: Humanitarian, Connoisseur, Collector, Scholar, Educator, Cherished Friend Front cover: Vanadite, Morocco Back cover: Malachite, Congo 1 NATURE’S ART: GEODES FROM THE COLLECTION OF ROBERT R. WIENER Guiding Light of The Rye Arts Center Robert R. Wiener exemplifies the Mission of The Rye Arts Center. He is a supporter of cultural endeavors for all and a staunch believer in extending the educational value of the arts to underserved populations. His largesse currently extends to the Center by his sharing geodes with us. This is the latest chapter of his enduring support that began thirty-five years ago. Bob is responsible for saving 51 Milton Road by spearheading in 1986 the movement to prevent the city’s demolition of our home. He then led the effort to renovate the building that we now occupy. As a member of the RAC Board in the 1980s and 1990s, Bob helped guide the Center through its early years of expansion and success. His efforts have enabled RAC to become a beacon of the arts for the local community and beyond it. Bob has joined with RAC to place cases of his geodes in area schools, where they attract excited attention from children and adults alike. Bob’s maxim is “The purpose of life is to give back.” Led and inspired by Bob, The Wiener Family Philanthropy supports dozens of organizations devoted to the arts, community initiatives, education, health care, and positive youth empowerment. -

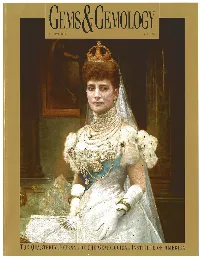

Fall 1993 Gems & Gemology

THEUUARTERLY JOURNAL OF THE bEMOLOGICAL INSTITUTE OF AMERICA TABL OF CONTENTS 1993 Challenge Winners Letters FEATURE ARTICLE Jewels of the Edwardians Elise B. Misiorowski and Nancy 1Z. Hays A Prospectors' Guide Map to the Gem Deposits of Sri Lanka C. B. Dissanayuke and M.S. Rupasinghe Two Treated-Color Synthetic Red Diamonds Seen in the Trade Thomas M. Moses, llene Reinitz, Emmanuel Fritsch, and James E, Shigley Two Near-Colorless General Electric Type-IIa Synthetic Diamond Crystals James E. Shigley, Emmanuel Fritsch, and llene Reinitz REGULAR FEATURES Gem Trade Lab Notes Gem News Book Reviews Gemological Abstracts ABOUT THE COVER: I. Snowman's circa-1910 portrait of Her Royal Highness Queen Alexandra, consort of King Edward VII of England, shows the plethora of iew- elry worn by ladies from the royal and wealthy upper classes of Europe and America at the turn of the 20th century. Alexandra's neck is wrapped with a pearl choker and many pearl necl<laces:the longest sautoir is pinned up in a swag effect using a pearl- and-diamond brooch. The gauzy tullle that decorates her ddcolletage is held in place by pins and brooches of every size and type, including a diamond star burst, a cres- cent, and two ruby-and-diamond bow brooches on either side of her neckline. Note the gold snake bracelet adorning her left wrist. The lead article in this issue exam- ines the styles, materials, and motifs of the elegant jewels favored by the distinctive group known as the Edwardians, who reigned as the leaders of high fashion in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. -

Agate Structures, Part 1 © 2015 Bill Kitchens

Agate Structures I: Formation and Classification of Common Agate Structures. Putting a Name on an Agate So, now we have some basic classifications of agates – those formed in volcanic host rocks and those formed in sedimentary host rocks. Agates that form in pockets, massive seam agates, and vein agates that are planar in shape. Then there are the fossil and mineral replacement agates that take the shape of the structure replaced. To those basics, we can add whole arrays of identifiers; some descriptive of patterns like fortification and moss or plume. Other identifiers are based on location like 'Lake Superior', 'Death Valley', 'Bloody Basin'; and some are proprietary trademarked names like 'Prudent Man' and 'Royal Aztec Lace'. Some of the more common terms describing the Brazilian Agate appearance of agate are wall banded, water-level, onyx, shadow, lace, eye, moss, plume, dendritic, tube, drape, sagenite, pseudomorph, geode, flame, stalactite, floating, brecciated, and ruin. Even stringing several of these classifiers together, as in “Laguna Lace”, or “Lake Superior Sagenite” can't adequately describe the simplest agate but it will put it in the ball park. Coming up is a section describing and attempting to explain some of the structures we see in agate. Realizing that one photo is worth a thousand words, we'll look at numerous of examples of these structures as we go along. Speaking of Agates and God, and Man – Agate Structures, Part 1 © 2015 Bill Kitchens Color and Color Banding Please recall from a few pages back (if you take these pdfs in series), that I spoke of crystallization and banding as inextricably interconnected, which they are – but also complexly interconnected. -

Artist Jewellery Is Enjoying a Renaissance. Aimee Farrell Looks At

Artist jewellery Right: Catherine Deneuve wearing Man Ray’s Pendantif-Pendant earrings in a photo by the artist, 1968. Below: Georges Braque’s Circé, 1962 brooch Photo: Sotheby’s France/ArtDigital Studio © Man Ray Trust/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017; Braque jewellery courtesy Diane Venet; all other jewellery shown here © Louisa Guinness Gallery Frame the face Artist jewellery is enjoying a renaissance. Aimee Farrell looks at its most captivating – and collectible – creations, from May Ray’s mega earrings to Georges Braque’s brooches 16 Fashion has long been in thrall of artist jewellery. In the 1930s, couturier Elsa Schiaparelli commissioned her circle of artist friends including Jean Cocteau and Alberto Giacometti to create experimental jewels for her collections; art world fashion plate Peggy Guggenheim boasted of being the only woman to Clockwise from left: wear the “enormous mobile earrings” conceived Man Ray’s La Jolie, 1970 pendant with lapis; The by kinetic artist Alexander Calder; and Yves Saint Oculist, 1971 brooch Laurent, a generous patron of the French husband- in gold and malachite; and his photograph of and-wife artist duo “Les Lalannes” summoned Claude Nancy Cunard, 1926 © Man Ray Trust/ADAGP, Lalanne to conjure a series of bronze breast plates, Paris and DACS, London akin to armour, for his dramatic autumn/winter 2017; Telimage, 2017 1969 show. So when Maria Grazia Chiuri enlisted Lalanne, now in her nineties, to devise the sculptural copper Man Ray jewels for her botanical-themed Christian Dior A brooch portraying Lee Miller’s lips, rings complete with tiny Couture debut this year, she put artist jewellery firmly tunnels that offer an alternative perspective on the world and 24 carat gold sunglasses – it’s no surprise that the avant-garde back on the agenda. -

GEMSTONES by Donald W

GEMSTONES By Donald W. Olson Domestic survey data and tables were prepared by Christine K. Pisut, statistical assistant, and the world production table was prepared by Glenn J. Wallace, international data coordinator. Gemstones have fascinated humans since prehistoric times. sustaining economically viable deposits (U.S. International They have been valued as treasured objects throughout history Trade Commission, 1997, p. 23). by all societies in all parts of the world. The first stones known The total value of natural gemstones produced in the United to have been used for making jewelry include amber, amethyst, States during 2001 was estimated to be at least $15.1 million coral, diamond, emerald, garnet, jade, jasper, lapis lazuli, pearl, (table 3). The production value was 12% less than the rock crystal, ruby, serpentine, and turquoise. These stones preceding year. The production decrease was mostly because served as status symbols for the wealthy. Today, gems are not the 2001 shell harvest was 13% less than in 2000. worn to demonstrate wealth as much as they are for pleasure or The estimate of 2001 U.S. gemstone production was based on in appreciation of their beauty (Schumann, 1998, p. 8). In this a survey of more than 200 domestic gemstone producers report, the terms “gem” and “gemstone” mean any mineral or conducted by the USGS. The survey provided a foundation for organic material (such as amber, pearl, and petrified wood) projecting the scope and level of domestic gemstone production used for personal adornment, display, or object of art because it during the year. However, the USGS survey did not represent possesses beauty, durability, and rarity. -

Early Diamond Jewelry See Inside Cover

ti'1 ;i' .{"n b"' HH :U 3 c-r 6E au) -:L _lH brD [! - eF o 3 Itr-| i:j,::]': O .a E cl!+ r-Ri =r l\+ - x':a @ o \<[SFs-X : R 9€ 9.!-o I* & = t t-Y ry ,;;4 fr o a ts(\ 3 tug -::- ^ ,9 QJH 7.oa : l-] X 'rr l]i @ ex b :<; i-o ld o o-! :. i (n z )@N -.; :!t Fml \"-DF i :\ =orD =\ ^:a -nft< oSr-n ppr= HDV '- s\C r 6- "?tJz* Jlt : ni . s' o c'l.!..4< F' ryl - i o5 F ; {: Ll-l> Fr \ ='/E<- a5. {E j*yt p.y. .o n O S_ sr = = i o - ;iar x'i@ xo ia\=i, -G; t- z i i *O ^ > :.r - : ' - , i--! i---:= -i -z-- l:-\i i- t-3 j'-a : =: S ---i--.-- a- F == :\- O z O - -- - a s =. e ?.a !':ii1 : = - / - . :: i *a !- z : C CI =2 7 \- ^ t =r- l! t! lv- Iv -5 ":. -_r ! c\ co =- \] N TJ ?ti:iE€ i; 5j:; LLI ;;tttE3 E;Ei!iiii'E ri l.T-1 j F-{ i aEE g;iij 1=,iE 3iE;i; ; a;E{ i ii is: :i E-r ''l FJ; l- r s r+ss U f{ r E ci! :?: i; E : nl L *ii;i;i;ili j Eiii!igiaiiiiii il -3€ ;l jii = c-l Le s it5 ;gt,*:ii;$ii; Fi F \JU a .lS IU H\ sit! gi;iig: g lJr )< :,i S i rsr ii: is Ei :n*J f,'i;i;t: a- -r UJ { FJi .i' E-u+Efi€ E sa !E ei E i E F-r tr< ;E;: iE; 3?$s?s t-J ;: z r'l .-u*s re,,r gs E;ig;lii:ii;:ii*5t.! ti:; +-J \ \H trl - L9 \ gEi F-r 'Eq E;*it[; ;i;E iE Hr IE €i;i ! i*;: I tr-r s ct) i EE:i:r! t E;fe; s E;ttsE H;i;{i; sE+ FJ-l S aS H5; e '-\ q/ E th i st*E;iuF€;EEEFi;iE;'a:€:; g F! n1 Ii;:i 3;t g;:s :;sErr; i;:ti i;;i: :E F rt;;;igic; iitiTEi :E ;: r ;ac i; I;; FiE$es;i* Hsi s=+ qE H;{;5FH $;!iiEg tJ L-J S- Nll ^llo.\ ll e*[r+;sir{+giiiE gEa,E s;ee=ltlfFE E5sfr;r ; +rfi [FE 1:8;$ il r;*;rc*€ i'[;*+EI tl ;i ili$;l$s rgiT;i;licE;{ i;E;fi il5! f,r 1l ;lFaE€iHiiifx;a$;as