A Brief Introduction to Aoki Rosui and Annotated Translation of His Text Otogi Hyaku Monogatari

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei By ©2016 Alison Miller Submitted to the graduate degree program in the History of Art and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko ________________________________ Dr. Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Dr. David Cateforis ________________________________ Dr. John Pultz ________________________________ Dr. Akiko Takeyama Date Defended: April 15, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Alison Miller certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko Date approved: April 15, 2016 ii Abstract This dissertation examines the political significance of the image of the Japanese Empress Teimei (1884-1951) with a focus on issues of gender and class. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Japanese society underwent significant changes in a short amount of time. After the intense modernizations of the late nineteenth century, the start of the twentieth century witnessed an increase in overseas militarism, turbulent domestic politics, an evolving middle class, and the expansion of roles for women to play outside the home. As such, the early decades of the twentieth century in Japan were a crucial period for the formation of modern ideas about femininity and womanhood. Before, during, and after the rule of her husband Emperor Taishō (1879-1926; r. 1912-1926), Empress Teimei held a highly public role, and was frequently seen in a variety of visual media. -

Kyoto Confidential

japan // asia K YOTO CONFIDENTIAL From the charming hot spring town of Kinosaki Onsen where visitors dress up to strip down, to a heritage fishing village unchanged in 300 years on the Sea of Japan… Rhonda Bannister veers off the tourist trail to discover the captivating treasures of Kyoto Prefecture 94 holidaysforcouples.travel 95 japan // asia Chilling in a hot spring Delving deeper into the Kyoto Prefecture (an administration area that’s a little like a state or territory), our next stop was around 100 kilometres north, on the Sea of Japan. Kinosaki Onsen is defined by its seven public bathhouses, dozens of ryokans (a traditional Japanese inn) with private hot spring baths, and a warm welcome wherever you wander. The town is adorable at first sight. The further we roamed the streets and laneways, criss-crossing the willow-lined Otani River on little stone bridges, the more enamoured we became – especially in the evening when lanterns bathe the river and trees in their seductive glow. The mystical history of Kinosaki Onsen fter the tourists have left and reaches back 1300 years when a Buddhist priest the streets are quiet, the ancient received a vision from an oracle telling him to area of Gion in Kyoto appears pray for a thousand days for the health of the straight from the pages of Memoirs people. Legend says that in addition to prayer, of a Geisha. This is one of Kyoto’s he fasted the entire time and on the last day, best-preservedA historical areas, and Japan’s most a hot spring shot up from the ground. -

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine

In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Patricia Shehan Campbell, Chair Jeffrey M. Perl Christina Sunardi Paul S. Atkins Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music ii ©Copyright 2017 Michiko Urita iii University of Washington Abstract In Silent Homage to Amaterasu: Kagura Secret Songs at Ise Jingū and the Imperial Palace Shrine in Modern and Pre-modern Japan Michiko Urita Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Patricia Shehan Campbell Music This dissertation explores the essence and resilience of the most sacred and secret ritual music of the Japanese imperial court—kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku—by examining ways in which these two songs have survived since their formation in the twelfth century. Kagura taikyoku and kagura hikyoku together are the jewel of Shinto ceremonial vocal music of gagaku, the imperial court music and dances. Kagura secret songs are the emperor’s foremost prayer offering to the imperial ancestral deity, Amaterasu, and other Shinto deities for the well-being of the people and Japan. I aim to provide an understanding of reasons for the continued and uninterrupted performance of kagura secret songs, despite two major crises within Japan’s history. While foreign origin style of gagaku was interrupted during the Warring States period (1467-1615), the performance and transmission of kagura secret songs were protected and sustained. In the face of the second crisis during the Meiji period (1868-1912), which was marked by a threat of foreign invasion and the re-organization of governance, most secret repertoire of gagaku lost their secrecy or were threatened by changes to their traditional system of transmissions, but kagura secret songs survived and were sustained without losing their iv secrecy, sacredness, and silent performance. -

Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture David Endresak [email protected]

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2006 Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture David Endresak [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Recommended Citation Endresak, David, "Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture" (2006). Senior Honors Theses. 322. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/322 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture Degree Type Open Access Senior Honors Thesis Department Women's and Gender Studies First Advisor Dr. Gary Evans Second Advisor Dr. Kate Mehuron Third Advisor Dr. Linda Schott This open access senior honors thesis is available at DigitalCommons@EMU: http://commons.emich.edu/honors/322 GIRL POWER: FEMININE MOTIFS IN JAPANESE POPULAR CULTURE By David Endresak A Senior Thesis Submitted to the Eastern Michigan University Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors in Women's and Gender Studies Approved at Ypsilanti, Michigan, on this date _______________________ Dr. Gary Evans___________________________ Supervising Instructor (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Kate Mehuron_________________________ Honors Advisor (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Linda Schott__________________________ Dennis Beagan__________________________ Department Head (Print Name and have signed) Department Head (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Heather L. S. Holmes___________________ Honors Director (Print Name and have signed) 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Printed Media.................................................................................................. -

Approach for International Exchange of River Restoration Technology

Approach for International Exchange of River Restoration Technology Ito, Kazumasa Head of planning office, Research Center for Sustainable Communities, CTI Engineering Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan Senior Councilor, Technical Coordination and Cooperation Division, Foundation for River Improvement and Restoration Tokyo, Japan Lecturer Musashi Institute of Technology Dept. of Civil Engineering Faculty of Engineering, Tokyo, Japan Abstract : About 50% of the population and 75% of the properties concentrate on the flood plain in Japan. The rivers have intimate relationship with our lives. Those conditions have been seen after modern river improvement projects that began about a century ago. The technology which was introduced from foreign countries was improved in conformity with geographical features and the climate condition of our nation, and has redeveloped as a Japanese original technology. In 1940's, Japan had serious natural disasters that were caused by large- scale typhoons. Those typhoons wiped out everything completely. Even though the government realized the importance of flood control and management after those natural disasters, civil work still aimed to economic development. Those construction works have become the one of factors for concentrating population and degrading natural environment in urban areas. Deterioration of river environment has become serious issue in urban development and main cause of pollution. The approaches for environmental restorations which were started about 30 years ago aimed to harmonize with nature environment and cities and human lives. There have been going on many projects called “river environmental improvement projects”, the “nature friendly river works” and “natural restoration projects.” The society has tried to find a way to live in harmony with nature. -

Kyoto Sightseeing Route

Imamiya-jinja Nearest bus stop ❾● Nearest bus stop ❾● Eizan Elec. Rwy. Specialty Shrine For Shimogamo-jinja Shrine For Ginkaku-ji Templeダミー銀閣寺の説明。□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□ Free Wi-Fi on board Operate every 5~10 min. Operate every 5~10 min. ( to Kibune/Kurama) Specialty SSID:skyhopbus_Free PW:skyhopbus ABURI MOCHIダミー金閣寺の説明。□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□ □□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□ 1 2 GOLD LEAF aitokuji 【Kyoto City Bus】 【Kyoto City Bus】 yoto ta. arasuma ojo roasted□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□D □□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□ Sky Hop K S K G SOFT CREAM rice cakes Bus route No.203 & No.102 BusKita-Oji route St. No.203 & No.102 □□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□Temple Bus □□□ Koto-in Karasuma Imadegawa Demachiyanagi Sta. Karasuma Imadegawa Ginkakuji-michi Ichijoji Sta. SKYHOP BUS Kyoto With Kyoto as the gateway to Hotel New Kyoto Tower ↑ Nearby Byodo-ji Temple was Temple 8 ※Walking about 3 min. from❾ ※Walking about 12 min. ※Walking about 3 min. from❾ ※Walking about 10 min. ダミー下鴨神社の説明。□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□ history, the station features a Hankyu Kyoto Hotel established when a statue of 2 Ryogen-in Temple to Shimogamo-jinja Shrine to Ginkaku-ji Temple (1 trip 99 min./every 30 min.) Kinkakuji 7 廬山寺 □□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□ Japanese Go board tile design. Yakushi Nyorai was drawn from ※A separate fare fromShimei the SkySt. Hop Bus Kyoto ticket is ※A separate fare from the Sky Hop Bus Kyoto ticket is Gojo Shimogamo Hon-dori St. Hon-dori Shimogamo □□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□ required. This fareKarasuma St. is 230 yen (one way). required. This fare is 230 yen (one way). Visitors from abroad will the sea and enshrined in 997. Temple □□□□ 500m 法然院 Subway Karasuma Line ダミー銀閣寺の説明。□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□ Tomb of Murasaki Shikibu 1 appreciate the large tourist Information 京都The principle image of Yakushi □□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□ Central Gojo St. -

Rites of Blind Biwa Players

ASIA 2017; 71(2): 567–583 Saida Khalmirzaeva* Rites of Blind Biwa Players DOI 10.1515/asia-2017-0034 Abstract: Not much is known about the past activities of blind biwa players from Kyushu. During the twentieth century a number of researchers and folklorists, such as Tanabe Hisao, Kimura Yūshō,KimuraRirō,Nomura(Ga) Machiko, Narita Mamoru, Hyōdō Hiromi and Hugh de Ferranti, collected data on blind biwa players in various regions of Kyushu, made recordings of their performances and conducted detailed research on the history and nature of their tradition. However, despite these efforts to document and publicize the tradition of blind biwa players and its representatives and their repertory, it ended around the end of the twentieth century. The most extensively docu- mented individual was Yamashika Yoshiyuki 山鹿良之 (1901–1996), one of the last representatives of the tradition of blind biwa players, who was known among researchers and folklorists for his skill in performing and an abundant repertory that included rites and a great many tales. Yamashika was born in 1901 in a farmer family in Ōhara of Tamana District, the present-day Kobaru of Nankan, Kumamoto Prefecture. Yamashika lost the sight in his left eye at the age of four. At the age of twenty-two Yamashika apprenticed with a biwa player named Ezaki Shotarō 江崎初太郎 from Amakusa. From his teacher Yamashika learned such tales as Miyako Gassen Chikushi Kudari 都合戦筑紫 下り, Kikuchi Kuzure 菊池くづれ, Kugami Gassen くがみ合戦, Owari Sōdō 尾張 騒動, Sumidagawa 隅田川 and Mochi Gassen 餅合戦. After three years Yamashika returned home. He was not capable of doing much farm work because his eyesight had deteriorated further by then. -

The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’S Subjugation of Silla

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1993 20/2-3 The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’s Subjugation of Silla Akima Toshio In prewar Japan, the mythical tale of Empress Jingii’s 神功皇后 conquest of the Korean kingdoms comprised an important part of elementary school history education, and was utilized to justify Japan5s coloniza tion of Korea. After the war the same story came to be interpreted by some Japanese historians—most prominently Egami Namio— as proof or the exact opposite, namely, as evidence of a conquest of Japan by a people of nomadic origin who came from Korea. This theory, known as the horse-rider theory, has found more than a few enthusiastic sup porters amone Korean historians and the Japanese reading public, as well as some Western scholars. There are also several Japanese spe cialists in Japanese history and Japan-Korea relations who have been influenced by the theory, although most have not accepted the idea (Egami himself started as a specialist in the history of northeast Asia).1 * The first draft of this essay was written during my fellowship with the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, and was read in a seminar organized by the institu tion on 31 January 199丄. 1 am indebted to all researchers at the center who participated in the seminar for their many valuable suggestions. I would also like to express my gratitude to Umehara Takeshi, the director general of the center, and Nakanism Susumu, also of the center, who made my research there possible. -

What Genji Paintings Do

Beyond Narrative Illustration: What Genji Paintings Do MELISSA McCORMICK ithin one hundred fifty years of its creation, gold found in the paper decoration of their accompanying cal- The Tale of Genji had been reproduced in a luxurious ligraphic texts (fig. 12). W set of illustrated handscrolls that afforded privileged In this scene from Chapter 38, “Bell Crickets” (Suzumushi II), for readers a synesthetic experience of Murasaki Shikibu’s tale. Those example, vaporous clouds in the upper right corner overlap directly twelfth-century scrolls, now designated National Treasures, with the representation of a building’s veranda. A large autumn survive in fragmented form today and continue to offer some of moon appears in thin outline within this dark haze, its brilliant the most evocative interpretations of the story ever imagined. illumination implied by the silver pigment that covers the ground Although the Genji Scrolls represent a singular moment in the his- below. The cloud patch here functions as a vehicle for presenting tory of depicting the tale, they provide an important starting point the moon, and, as clouds and mist bands will continue to do in for understanding later illustrations. They are relevant to nearly Genji paintings for centuries to come, it suggests a conflation of all later Genji paintings because of their shared pictorial language, time and space within a limited pictorial field. The impossibility of their synergistic relationship between text and image, and the the moon’s position on the veranda untethers the motif from literal collaborative artistic process that brought them into being. Starting representation, allowing it to refer, for example, to a different with these earliest scrolls, this essay serves as an introduction to temporal moment than the one pictured. -

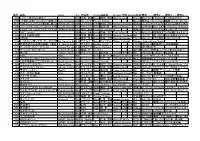

番号 曲名 Name インデックス 作曲者 Composer 編曲者 Arranger作詞

番号 曲名 Name インデックス作曲者 Composer編曲者 Arranger作詞 Words出版社 備考 備考2 備考3 備考4 595 1 2 3 ~恋がはじまる~ 123Koigahajimaru水野 良樹 Yoshiki鄕間 幹男 Mizuno Mikio Gouma ウィンズスコアWSJ-13-020「カルピスウォーター」CMソングいきものがかり 1030 17世紀の古いハンガリー舞曲(クラリネット4重奏)Early Hungarian 17thDances フェレンク・ファルカシュcentury from EarlytheFerenc 17th Hungarian century Farkas Dances from the Musica 取次店:HalBudapest/ミュージカ・ブダペスト Leonard/ハル・レナード編成:E♭Cl./B♭Cl.×2/B.Cl HL50510565 1181 24のプレリュードより第4番、第17番24Preludes Op.28-4,1724Preludesフレデリック・フランソワ・ショパン Op.28-4,17Frédéric福田 洋介 François YousukeChopin Fukuda 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2019年2月スコアは4番と17番分けてあります 840 スリー・ラテン・ダンス(サックス4重奏)3 Latin Dances 3 Latinパトリック・ヒケティック Dances Patric 尾形Hiketick 誠 Makoto Ogata ブレーンECW-0010Sax SATB1.Charanga di Xiomara Reyes 2.Merengue Sempre di Aychem sunal 3.Dansa Lationo di Maria del Real 997 3☆3ダンス ソロトライアングルと吹奏楽のための 3☆3Dance福島 弘和 Hirokazu Fukushima 音楽之友社バンドジャーナル2017年6月号サンサンダンス(日本語) スリースリーダンス(英語) トレトレダンス(イタリア語) トゥワトゥワダンス(フランス語) 973 360°(miwa) 360domiwa、NAOKI-Tmiwa、NAOKI-T西條 太貴 Taiki Saijyo ウィンズスコアWSJ-15-012劇場版アニメ「映画ドラえもん のび太の宇宙英雄記(スペースヒーローズ)」主題歌 856 365日の紙飛行機 365NichinoKamihikouki角野 寿和 / 青葉 紘季Toshikazu本澤なおゆき Kadono / HirokiNaoyuki Honzawa Aoba M8 QH1557 歌:AKB48 NHK連続テレビ小説『あさが来た』主題歌 685 3月9日 3Gatu9ka藤巻 亮太 Ryouta原田 大雪 Fujimaki Hiroyuki Harada ウィンズスコアWSL-07-0052005年秋に放送されたフジテレビ系ドラマ「1リットルの涙」の挿入歌レミオロメン歌 1164 6つのカノン風ソナタ オーボエ2重奏Six Canonic Sonatas6 Canonicゲオルク・フィリップ・テレマン SonatasGeorg ウィリアム・シュミットPhilipp TELEMANNWilliam Schmidt Western International Music 470 吹奏楽のための第2組曲 1楽章 行進曲Ⅰ.March from Ⅰ.March2nd Suiteグスタフ・ホルスト infrom F for 2ndGustav Military Suite Holst -

2020 H.C.Andersen Award Nominee from Japan

Yoko Tomiyasu 2020 H.C.Andersen Award Nominee from Japan 1 CONTENTS Biographical information .............................................................3 Statement ................................................................................4 Translation.............................................................................. 11 Bibliography and Awards .......................................................... 18 Five Important Titles with English text Mayu to Oni (Mayu & Ogree) ...................................................... 28 Bon maneki (Invitation to the Summer Festival of Bon) ......................... 46 Chiisana Suzuna hime (Suzuna the Little Mountain Godness) ................ 67 Nanoko sensei ga yatte kita (Nanako the Magical Teacher) ................. 74 Mujina tanteiktoku (The Mujina Ditective Agency) ........................... 100 2 © Yoko Tomiyasu © Kodansha Yoko Tomiyasu Born in Tokyo in 1959, Tomiyasu grew up listening to many stories filled with monsters and wonders, told by her grandmother and great aunts, who were all lovers of storytelling and mischief. At university she stud- ied the literature of the Heian period (the ancient Japanese era lasting from the 8th to 12 centuries AD). She was deeply attracted to stories of ghosts and ogres in Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji), and fell more and more into the world of traditional folklore. She currently lives in Osaka with her husband and two sons. There was a long era of writing stories that I wanted to read for myself. The origin of my creativity is the desire to write about a wonderous world that children can walk into from their everyday life. I want to write about the strange and mysterious world that I have loved since I was a child. 3 STATEMENT Recommendation of Yoko Tomiyasu for the Hans Christian Andersen Award Akira Nogami editor/critic Yoko Tomiyasu is one of Japan’s most popular Pond).” One hundred copies were printed. It authors and has published more than 120 was 1977 and Tomiyasu was 18. -

Yinger 1983-06.Pdf

, ~" " •. """~" > ACKN OWLEDGE1VIENTS This thesis has been an interna.tional effort, produced with trle cooperation of a grea.t many people in Japan~ Korea, England, and the United States. With no .i.l1tentionof diminishing the cor:tributi.qn of anyone not. mentioned below, I would like to single out a. few people for special thanks. I wish to thank the IJcmgwood Program at the University of Delavv"are for th8 award of the fell.owE}hip which helped to support this project. I am particularly indebted to my thesis committee--Dr. Richard W. Lighty, Mr. William H. Frederick, ,Jr., and Dr. Donald Huttleston-- for their very patient assistance. In Japan I wish to thank Dr. Sumihiko Hatsushima, Dr. FU"TIioMaekawa., Mr. Tadanori 'I'animura, Mr. Eiji Yamaha.ta, and Mr. NIatoshi Yoshida for patiently respondi.ng to my endless questions and for providing much of the research material cited herein. In addition, Mr. Yoshimichi Hirose, Mr. Mikinori Ogisu, Dr. Yotaro rrsuka.moto, and iii Dr. Ma,sato Yokol have earned my gratitude for directing me to useful research material. Among the many people who helped me in Japan, I must single out the efforts of Dr. Toshio Ando who so often arranged my itinerary in Japan and helped me with the translation of Japanese source material. For the privilege of examining herbarium specimens I wish to thank Dr. TchaT1;gBok 1,ee and h.is staff at Seoul. National University, Korea, and Mr. Ian Beier and his staff at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, England. My thanks too to Mr. Yong-,Jun Chang (Korea), Mr.