Labarque Creek Watershed Conservation Plan and Pledge Our Support for Its Contents and Implementation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hanging on to the Edges Hanging on to the Edges

DANIEL NETTLE Hanging on to the Edges Hanging on to the Edges Essays on Science, Society and the Academic Life D ANIEL Essays on Science, Society I love this book. I love the essays and I love the overall form. Reading these essays feels like entering into the best kind of intellectual conversati on—it makes me want and the Academic Life to write essays in reply. It makes me want to get everyone else reading it. I almost N never feel this enthusiasti c about a book. ETTLE —Rebecca Saxe, Professor of Cogniti ve Science at MIT What does it mean to be a scien� st working today; specifi cally, a scien� st whose subject ma� er is human life? Scien� sts o� en overstate their claim to certainty, sor� ng the world into categorical dis� nc� ons that obstruct rather than clarify its complexi� es. In this book Daniel Ne� le urges the reader to unpick such DANIEL NETTLE dis� nc� ons—biological versus social sciences, mind versus body, and nature versus nurture—and look instead for the for puzzles and anomalies, the points of Hanging on to the Edges connec� on and overlap. These essays, converted from o� en humorous, some� mes autobiographical blog posts, form an extended medita� on on the possibili� es and frustra� ons of the life scien� fi c. Pragma� cally arguing from the intersec� on between social and biological sciences, Ne� le reappraises the virtues of policy ini� a� ves such as Universal Basic Income and income redistribu� on, highligh� ng the traps researchers and poli� cians are liable to encounter. -

Meramec River Watershed Demonstration Project

MERAMEC RIVER WATERSHED DEMONSTRATION PROJECT Funded by: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency prepared by: Todd J. Blanc Fisheries Biologist Missouri Department of Conservation Sullivan, Missouri and Mark Caldwell and Michelle Hawks Fisheries GIS Specialist and GIS Analyst Missouri Department of Conservation Columbia, Missouri November 1998 Contributors include: Andrew Austin, Ronald Burke, George Kromrey, Kevin Meneau, Michael Smith, John Stanovick, Richard Wehnes Reviewers and other contributors include: Sue Bruenderman, Kenda Flores, Marlyn Miller, Robert Pulliam, Lynn Schrader, William Turner, Kevin Richards, Matt Winston For additional information contact East Central Regional Fisheries Staff P.O. Box 248 Sullivan, MO 63080 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Project Overview The overall purpose of the Meramec River Watershed Demonstration Project is to bring together relevant information about the Meramec River basin and evaluate the status of the stream, watershed, and wetland resource base. The project has three primary objectives, which have been met. The objectives are: 1) Prepare an inventory of the Meramec River basin to provide background information about past and present conditions. 2) Facilitate the reduction of riparian wetland losses through identification of priority areas for protection and management. 3) Identify potential partners and programs to assist citizens in selecting approaches to the management of the Meramec River system. These objectives are dealt with in the following sections titled Inventory, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Analyses, and Action Plan. Inventory The Meramec River basin is located in east central Missouri in Crawford, Dent, Franklin, Iron, Jefferson, Phelps, Reynolds, St. Louis, Texas, and Washington counties. Found in the northeast corner of the Ozark Highlands, the Meramec River and its tributaries drain 2,149 square miles. -

Fuller’S Leadership and Over- Vincent of the Refuge Staff Are Notable for Having Sight Were Invaluable

Acknowledgments Acknowledgments Many people have contributed to this plan over many detailed and technical requirements of sub- the last seven years. Several key staff positions, missions to the Service, the Environmental Protec- including mine, have been filled by different people tion Agency, and the Federal Register. Jon during the planning period. Tom Palmer and Neil Kauffeld’s and Nita Fuller’s leadership and over- Vincent of the Refuge staff are notable for having sight were invaluable. We benefited from close col- been active in the planning for the entire extent. laboration and cooperation with staff of the Illinois Tom and Neil kept the details straight and the rest Department of Natural Resources. Their staff par- of us on track throughout. Mike Brown joined the ticipated from the early days of scoping through staff in the midst of the process and contributed new reviews and re-writes. We appreciate their persis- insights, analysis, and enthusiasm that kept us mov- tence, professional expertise, and commitment to ing forward. Beth Kerley and John Magera pro- our natural resources. Finally, we value the tremen- vided valuable input on the industrial and public use dous involvement of citizens throughout the plan- aspects of the plan. Although this is a refuge plan, ning process. We heard from visitors to the Refuge we received notable support from our regional office and from people who care about the Refuge without planning staff. John Schomaker provided excep- ever having visited. Their input demonstrated a tional service coordinating among the multiple level of caring and thought that constantly interests and requirements within the Service. -

Surdex Case History Meramec Flooding Articlev Page 1.Eps

30 Hours from Acquisition to Online: Surdex’s Emergency Orthoimagery of the Meramec River Flood (2017) From Emergency Responders to local authorities to insurance companies, those responding to the flooding of Missouri’s Meramec River could access imagery within 30 hours of acquisition. Despite tremendous rains and poor atmospheric conditions, Surdex was able to capture critical imagery to help the community quickly respond to the disaster. The Meramec River Flood Area Missouri’s Meramec River is one of the largest free-flowing The Meramec crested on Wednesday, 3 May, at 36.52’, waterways in the state. Its meandering 220 miles drains breaking the over 100 year record by three feet. This was nearly 4,000 square miles in a watershed covering six preceded by a crest of 31.48’ on December 19, 2015 — Missouri counties. In late April 2017, the St. Louis region essentially exhibiting two nearly “100-year” floods within a experienced exceptionally heavy rains. In Sullivan, Missouri, 16-month period. The Meramec Caverns attraction was again nearly 7 inches of rain fell from April 29 through May 1. Local temporarily closed , along with several campgrounds, boat authorities watched with concern as the rivers swelled access areas, etc. beyond capacity. Being a St. Louis County-based company, Surdex monitored the flood waters and was able to conduct aerial imagery acquisition — despite the exceptionally cloudy and rainy conditions – to pull together a complete coverage of the flooded area for local communities and disaster recovery officials. Surdex was able to capture the imagery at a timely point during the flooding and use our tested With the projection that the flood would crest early on Wednesday, May 3, Surdex acquired aerial imagery on May emergency response processes to ensure 2, processed the images, and provided web services expedited products to the government and the containing the orthoimagery within 24 hours. -

Klondike Road Bridge HAER No. MO-71 (Votaw Road Bridge) Patf

Klondike Road Bridge HAER No. MO-71 (Votaw Road Bridge) patf? Spanning Big River at Klondike Road nrtcfc Morse Mill vicinity /77D Jefferson County SD-^on7 '' Vj Missouri , PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Engineering Record National Park Service Rocky Mountain Regional Office U. S. Department of the Interior P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD Klondike Road Bridge (Votaw Road Bridge) / - HAER No. MO-71 Original Location: The bridge was originally part of the Votaw Road Bridge over the Meramec River between Times Beach and Eureka from 1900 to 1933. Present Location: Spanning the Big River at Klondike Road Morse Mill vicinity, Jefferson County, Missouri UTM: Zone 15 N 4241040320 E 706950 Quad: Cedar Hill, 7.5 minute series Date of Construction: Built in 1900 as the two-span Votaw Road Bridge, one span was reconstructed in 1933 as the Klondike Road Bridge. Builder: St. Louis Bridge and Iron Company Present Owner: Jefferson County Courthouse Jefferson County Hillsboro, Missouri Present Use: Vehicular traffic bridge Significance: The bridge is the longest and oldest of eight surviving pinned Camelback through truss bridges in Missouri. The bridge is also the fifth longest of all the pinned through truss bridges in the state. Historians: Tom Gage, Ph.D., American History Craig Sturdevant, M.A., Anthropology John Carrel, Research Associate, ERC Klondike Road Bridge (Votaw Road Bridge) HAER No. MO-71 (Page 2) I. HISTORY The Votaw Road Bridge, later partially reconstructed in Jefferson County as the Klondike Road Bridge, was constructed across the Meramec River on the Votaw Road.1 The bridge provided the major thoroughfare between St. -

HIKING Fall Is Prime Time to Hit NW Trails

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2013 • VOLUME 107 • NO. 5 MountaineerE X P L O R E • L E A R N • C O N S E R V E HIKING Fall is prime time to hit NW trails INSIDE: 2013-14 Course Guide, pg. 13 Foraging camp cuisine, pg. 19 Bear-y season, pg. 21 Larches aglow, pg. 27 inside Sept/Oct 2013 » Volume 107 » Number 5 13 2013-14 Course Guide Enriching the community by helping people Scope out your outdooor course load explore, conserve, learn about, and enjoy the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. 19 Trails are ripe with food in the fall Foraging recipes for berries and shrooms 19 21 Fall can be a bear-y time of year Autumn is often when hiker and bear share the trail 24 Our ‘Secret Rainier’ Part III A conifer heaven: Crystal Peak 27 Fall is the right time for larches Destinations for these hardy, showy trees 37 A jewel in the Olympics 21 The High Divide is a challenge and delight 8 CONSERVATION CURRENTS Makng a case for the Wild Olympics 10 OUTDOOR ED Teens raising the bar in oudoor adventure 28 GLOBAL ADVENTURES European resorts: winter panaceas 29 WEATHERWISE 37 Indicators point to an uneventful fall and winter 31 MEMBERSHIP MATTERS October Board of Directors Elections 32 BRANCHING OUT See what’s going on from branch to branch 46 LAST WORD Innovation the Mountaineer uses . DISCOVER THE MOUNTAINEERS If you are thinking of joining—or have joined and aren’t sure where to start—why not set a date to meet The Mountaineers? Check the Branching Out section of the magazine (page 32) for times and locations of informational meetings at each of our seven branches. -

Flood-Inundation Maps for the Meramec River at Valley Park and at Fenton, Missouri, 2017

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, St. Louis Metropolitan Sewer District, Missouri Department of Transportation, Missouri American Water, and Federal Emergency Management Agency Region 7 Flood-Inundation Maps for the Meramec River at Valley Park and at Fenton, Missouri, 2017 Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5116 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Flooding from the Meramec River in Valley Park, Missouri. Upper left photograph taken December 30, 2015, by David Carson, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, used with permission. Lower right photograph taken December 31, 2015, by J.B. Forbes, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, used with permission. Back cover. Flooding from the Meramec River near Eureka, Missouri, December 30, 2015. Photographs by David Carson, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, used with permission. Flood-Inundation Maps for the Meramec River at Valley Park and at Fenton, Missouri, 2017 By Benjamin J. Dietsch and Jacob N. Sappington Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, St. Louis Metropolitan Sewer District, Missouri Department of Transportation, Missouri American Water, and Federal Emergency Management Agency Region 7 Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5116 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey William H. Werkheiser, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2017 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. -

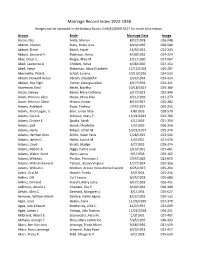

Marriage Record Index 1922-1938 Images Can Be Accessed in the Indiana Room

Marriage Record Index 1922-1938 Images can be accessed in the Indiana Room. Call (812)949-3527 for more information. Groom Bride Marriage Date Image Aaron, Elza Antle, Marion 8/12/1928 026-048 Abbott, Charles Ruby, Hallie June 8/19/1935 030-580 Abbott, Elmer Beach, Hazel 12/9/1922 022-243 Abbott, Leonard H. Robinson, Berta 4/30/1926 024-324 Abel, Oscar C. Ringle, Alice M. 1/11/1930 027-067 Abell, Lawrence A. Childers, Velva 4/28/1930 027-154 Abell, Steve Blakeman, Mary Elizabeth 12/12/1928 026-207 Abernathy, Pete B. Scholl, Lorena 10/15/1926 024-533 Abram, Howard Henry Abram, Elizabeth F. 3/24/1934 029-414 Absher, Roy Elgin Turner, Georgia Lillian 4/17/1926 024-311 Ackerman, Emil Becht, Martha 10/18/1927 025-380 Acton, Dewey Baker, Mary Cathrine 3/17/1923 022-340 Adam, Herman Glen Harpe, Mary Allia 4/11/1936 031-273 Adam, Herman Glenn Hinton, Esther 8/13/1927 025-282 Adams, Adelbert Pope, Thelma 7/14/1927 025-255 Adams, Ancil Logan, Jr. Eiler, Lillian Mae 4/8/1933 028-570 Adams, Cecil A. Johnson, Mary E. 12/21/1923 022-706 Adams, Crozier E. Sparks, Sarah 4/1/1936 031-250 Adams, Earl Snook, Charlotte 1/5/1935 030-250 Adams, Harry Meyer, Lillian M. 10/21/1927 025-376 Adams, Herman Glen Smith, Hazel Irene 2/28/1925 023-502 Adams, James O. Hallet, Louise M. 4/3/1931 027-476 Adams, Lloyd Kirsch, Madge 6/7/1932 028-274 Adams, Robert A. -

ED311449.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 449 CS 212 093 AUTHOR Baron, Dennis TITLE Declining Grammar--and Other Essays on the English Vocabulary. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1073-8 PUB DATE 89 NOTE :)31p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 10738-3020; $9.95 member, $12.95 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *English; Gr&mmar; Higher Education; *Language Attitudes; *Language Usage; *Lexicology; Linguistics; *Semantics; *Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS Words ABSTRACT This book contains 25 essays about English words, and how they are defined, valued, and discussed. The book is divided into four sections. The first section, "Language Lore," examines some of the myths and misconceptions that affect attitudes toward language--and towards English in particular. The second section, "Language Usage," examines some specific questions of meaning and usage. Section 3, "Language Trends," examines some controversial r trends in English vocabulary, and some developments too new to have received comment before. The fourth section, "Language Politics," treats several aspects of linguistic politics, from special attempts to deal with the ethnic, religious, or sex-specific elements of vocabulary to the broader issues of language both as a reflection of the public consciousness and the U.S. Constitution and as a refuge for the most private forms of expression. (MS) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY J. Maxwell TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." U S. -

Remedial Investigation Report, Chemsol Inc. Superfund Site

REMEDIAL INVESTIGATION REPORT CHEM8OL INC. SUPERFUND SITE PREPARED FOR: U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY REGION II VOLUME I OCTOBER 1996 CDM FEDERAL PROGRAMS CORPORATION a subsidiary of Camp Dresser & McKee Inc. REMEDIAL INVESTIGATION REPORT CHEMSOL INC. SUPERFUND SITE PISCATAWAY TOWNSHIP, MIDDLESEX COUNTY, NEW JERSEY Prepared for U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY, REGION H 290 Broadway New York, New York FPA Work Assignment No. 046-2LC3 EPA Region n Contract No. 68-W9-C024 CDM Federal Programs Corporation Document No. 7720-046-RI-CLYK Prepared By CDM FEDERAL PROGRAMS CORPORATION Work Assignment Man&ger Maheyar R. Bilimoria Telephone Number (212) 785-9123 EPA Work Assignment Manager James S. HakJar Telephone Number (212) 637-4414 Date Prepared October 17, 1996 Federal Programs Corporation A Subsidiary of Camp Dresser S McKee Inc 125 Maiden Lane. 5th Floor New York. New York 10038 Tel: 212 785-9123 Fax:212785-6114 October 17, 1996 Ms. Alison Devine Project Officer U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 290 Broadway, 18th Floor, Rm E34 New York, NY 10007-1866 Mr. James S. Haklar, P.E. Remedial Project Manager U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 290 Broadway, 19th Floor, Rm W32 New York, NY 10007-1866 PROJECT: ARCS H Contract No. 68-W9-0024 Work Assignment 046-2LC3 DCN: 7720-046-EP-CLYJ SUBJECT: Remedial Investigation Report Chemsol, Inc. Site, Township of Piscataway, Middlesex County, New Jersey Dear Ms. Devine and Mr. Haklar: CDM FEDERAL PROGRAMS CORPORATION (COM Federal) is pleased to submit this Remedial Investigation Report for the Chemsol, Inc. Superfund Site in Piscataway, New Jersey. CDM Federal has incorporated EPA's comments. -

HONOR ROLL of DONORS 1 Mack D

FALL 2014 Recognition of and appreciation for those donors Honor Roll who made a gift to support the students of Le Moyne College from June 1, 2013 to May 31, 2014 of Donors By the time Le Moyne’s 14th president, Linda Le Mura, Ph.D., welcomed the members of the College’s largest-ever freshman class to campus in August, they already had completed their first assignment. As part of the new Core Curriculum, the Freshman Seminar requires that every student, whether studying biological sciences, finance or film, read, most for the first time, a classic, canonical text to introduce them to the practice of academic inquiry. As one of the few colleges to expect as much from its incoming freshmen, Le Moyne has earned kudos from the National Association of Scholars. The Narrative of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave is not an easy read. It is neither fluid nor simple. It demands fortitude and rigor, and challenged the freshman to confront difficult and complex questions about the human condition. Will this reading transform these students? Will it help them land a job in four years? Will it be worth the investment? The answer is yes … if they are willing to push through the complexity and not give up. These young men and women will live and work in a complicated world, and Le Moyne’s president, faculty and staff are committed to helping them to meet the challenges and opportunities ahead. Throughout the College’s history, great leaders and teachers – including Don Monan, S.J., Hap Ridley, S.J., Robert O’Brien, S.J., Charles McCain, Ph.D, Dr. -

Index to Register of Death 1881-1920

Index to Register of Deaths Town of Oyster Bay Compiled by Town Historian John E. Hammond When Theodore Roosevelt died in 1919 his death was duly recorded by Oyster Bay Town Clerk Charles Weeks. Roosevelt was buried in Youngs Memorial Cemetery on January 8, 1919. RICHARD LaMARCA JOHN E. HAMMOND Town Clerk Town Historian A Message from Town Clerk RICHARD LaMARCA Dear Genealogy Enthusiast, Death certificates are filled with useful information for anyone compiling a family genealogy. While most states started requiring death certificates around the turn of the last century, the Town of Oyster Bay has records dating back to 1881. This booklet now does a lot of the work for you by listing those death certificates filed in the Town of Oyster Bay between the years 1881 to 1920. If you have been working on your family’s genealogy for a while, you are probably familiar with these little treasure troves. However, if you’re just starting out, you may not be aware of the valuable data they contain. Gener-ally speaking, the Towns’ death certificates include the name of the deceased, the deceased’s date and place of birth, the cause of death, the deceased’s place of burial, the names and birth places of both parents (a death certificate is a great resources for maiden names), and the name of the doctor. Just a word of caution: These are not perfect documents. Usually, the infor-mation was supplied by a relative, also known as the “informant.” This means the information was correct if the person knew it or could recall it under rather emotional circumstances.