A Critical Study of Western Views on Hadith with Special Reference to the Views of James Robson and John Burton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hérésies : Une Construction D’Identités Religieuses

Hérésies : une construction d’identités religieuses Quelles sortes de communautés réunissent les hommes ? Comment sont- elles construites ? Où est l’unité, où est la multiplicité de l’humanité ? Les hommes peuvent former des communautés distinctes, antagonistes, s’opposant violemment. La division externe est-elle nécessaire pour bâtir une cohésion interne ? Rien n’est plus actuel que ces questions. Parmi toutes ces formes de dissensions, les études qui composent ce volume s’intéressent à l’hérésie. L’hérésie se caractérise par sa relativité. Nul ne se revendique hérétique, sinon par provocation. Le qualificatif d’hérétique est toujours subi par celui qui le porte et il est toujours porté DYE BROUWER, GUILLAUME CHRISTIAN PAR EDITE ROMPAEY VAN ET ANJA Hérésies : une construction sur autrui. Cela rend l’hérésie difficilement saisissable si l’on cherche ce qu’elle est en elle-même. Mais le phénomène apparaît avec davantage de clarté si l’on analyse les discours qui l’utilisent. Se dessinent dès lors les d’identités religieuses représentations qui habitent les auteurs de discours sur l’hérésie et les hérétiques, discours généralement sous-tendus par une revendication à EDITE PAR CHRISTIAN BROUWER, GUILLAUME DYE ET ANJA VAN ROMPAEY l’orthodoxie. Hérésie et orthodoxie forment ainsi un couple, désuni mais inséparable. Car du point de vue de l’orthodoxie, l’hérésie est un choix erroné, une déviation, voire une déviance. En retour, c’est bien parce qu’un courant se proclame orthodoxe que les courants concurrents peuvent être accusés d’hérésie. Sans opinion correcte, pas de choix déviant. La thématique de l’hérésie s’inscrit ainsi dans les questions de recherche sur l’altérité religieuse. -

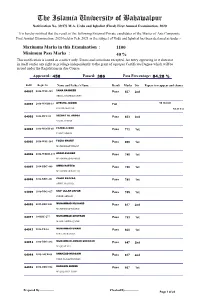

M.A Urdu and Iqbaliat (Final)

The Islamia University of Bahawalpur Notification No. 39/CS M.A. Urdu and Iqbaliat (Final) First Annual Examination, 2020 It is hereby notified that the result of the following External/Private candidates of the Master of Arts Composite First Annual Examination, 2020 held in Feb, 2021 in the subject of Urdu and Iqbaliat has been declared as under:- Maximum Marks in this Examination : 1100 Minimum Pass Marks : 40 % This notification is issued as a notice only. Errors and omissions excepted. An entry appearing in it does not in itself confer any right or privilege independently to the grant of a proper Certificate/Degree which will be issued under the Regulations in due Course. -5E -4E Appeared: 458 Passed: 386 Pass Percentage: 84.28 % Roll# Regd. No Name and Father's Name Result Marks Div Papers to reappear and chance 64001 2016-WST-348 SANA RASHEED Pass 637 2nd ABDUL RASHEED KHAN VII IX X XI 64002 2016-WNDR-19 AYESHA JAVAID Fail JAVAID AKHTAR R/A till S-22 64003 2014-IWY-88 SEERAT UL AROOJ Pass 653 2nd NASIR AHMAD 64004 2016-MOCB-05 FAZEELA BIBI Pass 712 1st JAM GAMMON 64005 2016-WST-164 FOZIA SHARIF Pass 690 1st MUHAMMAD SHARIF 64006 2016-WBDR-173 ANAM ASGHAR Pass 740 1st MUHAMMAD ASGHAR 64007 2018-BDC-440 AMNA RAFEEQ Pass 730 1st MUHAMMAD RAFEEQ 64008 2016-BDC-481 ZAHID RAZZAQ Pass 741 1st ABDUL RAZZAQ 64009 2016-BDC-427 SAIF ULLAH ZAFAR Pass 745 1st ZAFAR AHMAD 64010 2015-BDC-623 MUHAMMAD MUJAHID Pass 617 2nd MUHAMMAD AKRAM 64011 10-BDC-277 MUHAMMAD GHUFRAN Pass 753 1st MALIK ABDUL QADIR 64012 2016-US-16 MUHAMMAD UMAIR Pass 660 1st GHULAM RASOOL 64013 2016-BDC-434 MUHAMMAD AHMAD SHEHZAD Pass 647 2nd LIAQUAT ALI 64014 2015-AICB-08 SHAHZAD HUSSAIN Pass 617 2nd SYED SAJJAD HUSSAIN 64015 2016-BDC-542 HASNAIN AHMED Pass 667 1st MULAZIM HUSSAIN Prepared By--------------- Checked By-------------- Page 1 of 24 Roll# Regd. -

UC Santa Barbara Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Protestant Missions, Seminaries and the Academic Study of Islam in the United States A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Religious Studies by Caleb D. McCarthy Committee in charge: Professor Juan E. Campo, Chair Professor Kathleen M. Moore Professor Ann Taves June 2018 The dissertation of Caleb D. McCarthy is approved. _____________________________________________ Kathleen M. Moore _____________________________________________ Ann Taves _____________________________________________ Juan E. Campo, Committee Chair June 2018 Protestant Missions, Seminaries and the Academic Study of Islam in the United States Copyright © 2018 by Caleb D. McCarthy iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS While the production of a dissertation is commonly idealized as a solitary act of scholarly virtuosity, the reality might be better expressed with slight emendation to the oft- quoted proverb, “it takes a village to write a dissertation.” This particular dissertation at least exists only in light of the significant support I have received over the years. To my dissertation committee Ann Taves, Kathleen Moore and, especially, advisor Juan Campo, I extend my thanks for their productive advice and critique along the way. They are the most prominent among many faculty members who have encouraged my scholarly development. I am also indebted to the Council on Information and Library Research of the Andrew C. Mellon Foundation, which funded the bulk of my archival research – without their support this project would not have been possible. Likewise, I am grateful to the numerous librarians and archivists who guided me through their collections – in particular, UCSB’s retired Middle East librarian Meryle Gaston, and the Near East School of Theology in Beriut’s former librarian Christine Linder. -

Amr and Muawiya Pact

Edinburgh Research Explorer The Pact (amna) Between Muwiya Ibn Ab Sufyn and Amr Ibn Al- (656 or 658 CE) Citation for published version: Marsham, A 2012, 'The Pact (amna) Between Muwiya Ibn Ab Sufyn and Amr Ibn Al- (656 or 658 CE): ‘Documents’ and the Islamic Historical Tradition', Journal of Semitic Studies, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 69-96. https://doi.org/10.1093/jss/fgr034 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1093/jss/fgr034 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Early version, also known as pre-print Published In: Journal of Semitic Studies Publisher Rights Statement: © Marsham, Andrew / The Pact (amna) Between Muwiya Ibn Ab Sufyn and Amr Ibn Al- (656 or 658 CE) : ‘Documents’ and the Islamic Historical Tradition. In: Journal of Semitic Studies, Vol. 57, No. 1, 2012, p. 69-96. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 The Pact (amāna) between Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān and ʿAmr ibn al-ʿĀṣ (656 or 658 CE): ‘Documents’ and the Islamic Historical Tradition* Andrew Marsham University of Edinburgh The limits of uncritical approaches to the Islamic historical tradition are now widely accepted. -

A Textual Analysis of the Hadīths of Āishah's Age at the Time of Her Marriage to the Prophet Muhammad (Saw)

A Textual Analysis of the Hadīths of Āishah’s Age at the Time of Her Marriage to the Prophet Muhammad (saw) “Hz. Âişe’nin Hz. Peygamber (s.a.v.) ile Evlendiğindeki Yaşına Sulaiman Kamal-deen OLAWALE, Dr.* Dair Hadislerin Metin Tenkîdi” Özet: Bu makale, Hz. Âişe’nin Hz. Peygamber ile söz kesildiğinde altı, zifafa girdiğine ise dokuz yaşında olduğuna dair hadislerin tenkîdî bir tahlîlini konu edinmektedir. Bu konuya dair hadisler İslâm’da, genellikle çocuk yaştaki çocukların evlendirilmesinin câiz olduğu inancına yol açmıştır. Bu meseleye yönelik, İslâm dünyasında karışık bir tepki meydana getirmiştir. Bazı kimseler Hz. Âişe’nin, Hz. Peygamberin eşi olarak evine girdiğinde dokuz yaşında olduğunda ısrar ederken, diğer bir kesim de on dokuz yaşında olduğunu savunmuştur. Sözkonusu yaklaşım, Kur’ân-ı Kerîm ve hadisler yanında tamamıyla el yazmaları, kitaplar, akademik dergiler, internet, dergiler gibi tamamen yazılı kaynaklardan hareketle ortaya konulmuştur. Bu çalışma, Hz. Âişe’nin yaşının hadislerin rivâyeti esnasında ciddi derecede yanlış rivâyet edildiğini ortaya koymaktadır. Kaldı ki, bu olayı tarihî verilere dayalı olarak anlatan rivâyetler güvenilirliğin üst düzeyinde değildir. Bu makale, konuyu nesnel bir noktadan ele almayı önermekte ve şayet Hz. Peygamber (s.a.v.) insanlık için bir modelse ve hayatı boyunca Kur’ân’a göre hayat sürdüyse ve Allah Kur’ân’da onun sağlam karakterine şâhitlik etmişse, onun altı veya dokuz yaşında, olgunlaşmamış, oyun çağında bir kız çocuğu ile evlenemeyeceği sonucuna ulaşmaktadır. Atıf: Sulaiman Kamal-deen OLAWALE, “A Textual Analysis of the Hadīths of Āishah’s Age at the Time of Her Marriage to the Prophet Muhammad (saw)”, Hadis Tetkikleri Dergisi, (HTD), XII/1, 2014, ss. 23-34. -

Ignaz Goldziher Example

147-105 :5 ,2020 / ديسمبر / Aralık / December A Study on the Historical Foundations of Jewish Orientalism: Ignaz Goldziher Example Yahudi Oryantalizminin Tarihi Temelleri Üzerine Bir Araştırma: Ignaz Goldziher Örneği دراسة حول ا ألسس التارخيية لﻻسترشاق الهيودي: اجنا س جودلتس هير منوذج ا Hafize Yazıcı Arş. Gör. Atatürk Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi, Erzurum/Türkiye Res. Ast., Ataturk University Faculty of Theology, Erzurum/Turkey [email protected] ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6675-5890 Makale Bilgisi | Article Information Makalenin Türü / Article Type : Araştırma Makalesi / Research Article Geliş Tarihi / Received Date: 12.12.2020 Kabul Tarihi / Accepted Date: 30.12.2020 Yayın Tarihi / Published Date: 31.12.2020 Yayın Sezonu / Publication Date Season: Aralık / December DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4429234 Yazıcı, Hafize. “A Study on the Historical Foundations of Jewish Orientalism: Ignaz Goldziher : ا قتباس / Atıf / Citation Example / Yahudi Oryantalizminin Tarihi Temelleri Üzerine Bir Araştırma: Ignaz Goldziher Örneği”. HADITH 5 (Aralık/December 2020): 105-147. doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4429234. İntihal: Bu makale, iTenticate yazılımınca taranmıştır. İntihal tespit edilmemiştir. Plagiarism: This article has been scanned by iThenticate. No plagiarism has been detected. انتحال: مت فحص البحث بواسطة برانمج ﻷجل السرقة العلمية فلم يتم إجياد أي سرقة علمية. web: http://dergipark.gov.tr/hadith | mailto: [email protected] HADITH 5 (Aralık/December 2020): 105-147 A Study on the Historical Foundations of Jewish Orientalism: Ignaz Goldziher Example Hafize YAZICI Keywords: ABSTRACT Jewish Orientalism While Christians had a long history of Islamic Studies in the West, Jewish also made remarkable Islām contributions to this field beginning from the early periods, and they have had a pioneering role Judaism in this field thanks to the scientists they educated. -

Remembering Joseph Schacht (1902‑1969) by Jeanette Wakin ILSP

ILSP Islamic Legal Studies Program Harvard Law School Remembering Joseph Schacht (1902-1969) by Jeanette Wakin Occasional Publications January © by the Presdent and Fellows of Harvard College All rghts reserved Prnted n the Unted States of Amerca ISBN --- The Islamic Legal Studies Program s dedcated to achevng excellence n the study of Islamc law through objectve and comparatve methods. It seeks to foster an atmosphere of open nqury whch em- braces many perspectves, both Muslm and non-Mus- lm, and to promote a deep apprecaton of Islamc law as one of the world’s major legal systems. The man focus of work at the Program s on Islamc law n the contemporary world. Ths focus accommodates the many nterests and dscplnes that contrbute to the study of Islamc law, ncludng the study of ts wrt- ngs and hstory. Frank Vogel Director Per Bearman Associate Director Islamc Legal Studes Program Pound Hall Massachusetts Ave. Cambrdge, MA , USA Tel: -- Fax: -- E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/ILSP Table of Contents Preface v Text, by Jeanette Wakin Bblography v Preface The followng artcle, by the late Jeanette Wakn of Columba Unversty, a frend of our Program and one of the leaders n the field of Islamc legal studes n the Unted States, memoralzes one of the most famous of Western Islamc legal scholars, her men- tor Joseph Schacht (d. ). Ths pece s nvaluable for many reasons, but foremost because t preserves and relably nterprets many facts about Schacht’s lfe and work. Equally, however—especally snce t s one of Prof. -

University of Lo Ndo N Soas the Umayyad Caliphate 65-86

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SOAS THE UMAYYAD CALIPHATE 65-86/684-705 (A POLITICAL STUDY) by f Abd Al-Ameer 1 Abd Dixon Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philoso] August 1969 ProQuest Number: 10731674 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731674 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2. ABSTRACT This thesis is a political study of the Umayyad Caliphate during the reign of f Abd a I -M a lik ibn Marwan, 6 5 -8 6 /6 8 4 -7 0 5 . The first chapter deals with the po litical, social and religious background of ‘ Abd al-M alik, and relates this to his later policy on becoming caliph. Chapter II is devoted to the ‘ Alid opposition of the period, i.e . the revolt of al-Mukhtar ibn Abi ‘ Ubaid al-Thaqafi, and its nature, causes and consequences. The ‘ Asabiyya(tribal feuds), a dominant phenomenon of the Umayyad period, is examined in the third chapter. An attempt is made to throw light on its causes, and on the policies adopted by ‘ Abd al-M alik to contain it. -

Khwaja Abdul Hamied

On the Margins <UN> Muslim Minorities Editorial Board Jørgen S. Nielsen (University of Copenhagen) Aminah McCloud (DePaul University, Chicago) Jörn Thielmann (Erlangen University) volume 34 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/mumi <UN> On the Margins Jews and Muslims in Interwar Berlin By Gerdien Jonker leiden | boston <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: The hiking club in Grunewald, 1934. PA Oettinger, courtesy Suhail Ahmad. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Jonker, Gerdien, author. Title: On the margins : Jews and Muslims in interwar Berlin / by Gerdien Jonker. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2020] | Series: Muslim minorities, 1570–7571 ; volume 34 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019051623 (print) | LCCN 2019051624 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004418738 (hardback) | ISBN 9789004421813 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Jews--Germany--Berlin--Social conditions--20th century. | Muslims--Germany--Berlin--Social conditions--20th century. | Muslims --Cultural assimilation--Germany--Berlin. | Jews --Cultural assimilation --Germany--Berlin. | Judaism--Relations--Islam. | Islam --Relations--Judaism. | Social integration--Germany--Berlin. -

International Conference on Qur'an and Hadith Studies (ICQHS 2017)

International Conference on Qur’an and Hadith Studies (ICQHS 2017) Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research Volume 137 Jakarta, Indonesia 6 – 8 November 2017 Editors: Yusuf Rahman Kusmana ISBN: 978-1-5108-5695-0 Printed from e-media with permission by: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 Some format issues inherent in the e-media version may also appear in this print version. Copyright© (2018) by Atlantis Press All rights reserved. http://www.atlantis-press.com/php/pub.php?publication=icqhs-17 Printed by Curran Associates, Inc. (2018) For permission requests, please contact the publisher: Atlantis Press Amsterdam / Paris Email: [email protected] Additional copies of this publication are available from: Curran Associates, Inc. 57 Morehouse Lane Red Hook, NY 12571 USA Phone: 845-758-0400 Fax: 845-758-2633 Email: [email protected] Web: www.proceedings.com TABLE OF CONTENTS A CONTEXTUAL METHOD OF INTERPRETING THE QUR'AN: A SEARCH FOR THE COMPATIBILITY OF ISLAM AND MODERNITY ........................................................................................................1 Dede Rosyada FREEDOM OF RELIGION IN RASHID RIDA'S PERSPECTIVE ................................................................................7 Moh. Abdul Kholiq Hasan MODERN THEOLOGICAL READING OF THE QUR'AN, AND GENDER ISSUES: THREE CASES OF FEMALE MUSLIM SCHOLARS ................................................................................................................. 11 Kusmana "GOD IS BEYOND SEX/GENDER" -

Non-Muslim Integration Into the Early Islamic Caliphate Through the Use of Surrender Agreements

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK History Undergraduate Honors Theses History 5-2020 Non-Muslim Integration Into the Early Islamic Caliphate Through the Use of Surrender Agreements Rachel Hutchings Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/histuht Part of the History of Religion Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Citation Hutchings, R. (2020). Non-Muslim Integration Into the Early Islamic Caliphate Through the Use of Surrender Agreements. History Undergraduate Honors Theses Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/histuht/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Non-Muslim Integration Into the Early Islamic Caliphate Through the Use of Surrender Agreements An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Honors Studies in History By Rachel Hutchings Spring 2020 History J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences The University of Arkansas 1 Acknowledgments: For my family and the University of Arkansas Honors College 2 Table of Content Introduction…………………………………….………………………………...3 Historiography……………………………………….…………………………...6 Surrender Agreements…………………………………….…………….………10 The Evolution of Surrender Agreements………………………………….…….29 Conclusion……………………………………………………….….….…...…..35 Bibliography…………………………………………………………...………..40 3 Introduction Beginning with Muhammad’s forceful consolidation of Arabia in 631 CE, the Rashidun and Umayyad Caliphates completed a series of conquests that would later become a hallmark of the early Islamic empire. Following the Prophet’s death, the Rashidun Caliphate (632-661) engulfed the Levant in the north, North Africa from Egypt to Tunisia in the west, and the Iranian plateau in the east. -

Modern Hadith Studies Between Arabophone and Western Scholarship 09-10 January 2017

CALL FOR PAPERS Modern Hadith Studies Between Arabophone and Western Scholarship 09-10 January 2017 Organised by: Belal Alabbas, Prof. Christopher Melchert, Dr Nicolai Sinai Pembroke College, University of Oxford Hadith literature is part and parcel of disciplines related to Islam and Muslim societies. At some point during their research scholars are likely to encounter primary sources containing hadith material related to history, law, sociology, or the complex science of kalam. However, hadith studies present two significant challenges. First, the hadith corpus is immense and large parts of it remain insufficiently explored. Second, it has bifurcated the world of Islamicists to a sceptic and a sanguine. Many academic scholars in the Arab world continue to view the study of hadith in Western secular universities as a colonialist project that aims to attack the tenets of Islam. The inverse also holds, whereby scholars in secular universities in the Anglophone view Islamic scholarship on the hadith corpus as biased and uncritical. The absence of proper scholarly interaction between both scholarly communities is deplorable and unnecessary, given that some of their premises, methods, and results actually exhibit significant convergence. This conference therefore invites scholars from Arabophone and Western institutions to discuss current research on the hadith corpus, aiming to bridge the divide between Anglophone and Arabophone research in hadith studies. It is based on the belief that the absence of any engagement of the scholarly communities with one another inhibits any significant methodological convergence. A more sustained dialogue and debate between scholars from various disciplines would bring to light further areas of historiographical and methodological agreement, provide stimuli for further research, and facilitate a mutually beneficial exchange of expertise.