Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Janson. History of Art. Chapter 16: The

16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 556 16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 557 CHAPTER 16 CHAPTER The High Renaissance in Italy, 1495 1520 OOKINGBACKATTHEARTISTSOFTHEFIFTEENTHCENTURY , THE artist and art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote in 1550, Truly great was the advancement conferred on the arts of architecture, painting, and L sculpture by those excellent masters. From Vasari s perspective, the earlier generation had provided the groundwork that enabled sixteenth-century artists to surpass the age of the ancients. Later artists and critics agreed Leonardo, Bramante, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giorgione, and with Vasari s judgment that the artists who worked in the decades Titian were all sought after in early sixteenth-century Italy, and just before and after 1500 attained a perfection in their art worthy the two who lived beyond 1520, Michelangelo and Titian, were of admiration and emulation. internationally celebrated during their lifetimes. This fame was For Vasari, the artists of this generation were paragons of their part of a wholesale change in the status of artists that had been profession. Following Vasari, artists and art teachers of subse- occurring gradually during the course of the fifteenth century and quent centuries have used the works of this 25-year period which gained strength with these artists. Despite the qualities of between 1495 and 1520, known as the High Renaissance, as a their births, or the differences in their styles and personalities, benchmark against which to measure their own. Yet the idea of a these artists were given the respect due to intellectuals and High Renaissance presupposes that it follows something humanists. -

Vincenzo Cappello C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Sixteenth Century Titian and Workshop Titian Venetian, 1488/1490 - 1576 Italian 16th Century Vincenzo Cappello c. 1550/1560 oil on canvas overall: 141 x 118.1 cm (55 1/2 x 46 1/2 in.) framed: 169.2 x 135.3 x 10.2 cm (66 5/8 x 53 1/4 x 4 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1957.14.3 ENTRY This portrait is known in at least four other contemporary versions or copies: in the Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, Virginia[fig. 1]; [1] in the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg [fig. 2]; [2] in the Seminario Vescovile, Padua; [3] and in the Koelikker collection, Milan. [4] According to John Shearman, x-radiographs have revealed that yet another version was originally painted under the Titian workshop picture Titian and His Friends at Hampton Court (illustrated under Andrea de’ Franceschi). [5] Of these versions, the Gallery’s picture is now generally accepted as the earliest and the finest, and before it entered the Kress collection in 1954, the identity of the sitter, established by Victor Lasareff in 1923 with reference to the Hermitage version, has never subsequently been doubted. [6] Lasareff retained a traditional attribution to Tintoretto, and Rodolfo Pallucchini and W. R. Rearick upheld a similarly traditional attribution to Tintoretto of the present version. [7] But as argued by Wilhelm Suida in 1933 with reference to the Chrysler version (then in Munich), and by Fern Rusk Shapley and Harold Wethey with reference to the present version, an attribution to Titian is more likely. -

An Examination of a Seventeenth- Century Copy of Raphael’S Holy Family, C.1518

Uncovering the Original: An Examination of a Seventeenth- Century copy of Raphael’s Holy Family, c.1518. Annie Cornwell, Postgraduate in the Conservation of Easel Paintings Amalie Juel, MA Art History Uncovering the Original: An Examination of a 17th-Century copy of Raphael’s The Holy Family, c. 1518, The Prado Madrid. Introduction to The Project: This report has been written as part of the annual project Conservation and Art Historical Analysis, presented by the Sackler Research Forum at the Courtauld Institute of Art. Seeking to encourage collaboration between art historians and conservators, the scheme brings together two students - one from postgraduate art history and the other from easel paintings conservation - to complete an in-depth research project on a single piece of art. By doing so, the project allows a multifaceted approach combining historical research with technical analysis and, in this case, conservation treatment of the work in question. Focusing on the painting as a physical object with a material history, the project shows the value of combining art history with the more scientific aspects of the field of conservation. The focus of this project is a painting of the Virgin and Child with Saints Anne and John - a copy of Raphael’s Holy Family from the Prado - of unknown artist and date. It is owned by St Patrick’s Catholic Church in Wapping, where it had been recently found in a cupboard underneath the stairs. It came into the Courtauld Conservation Department to be treated by Annie Cornwell in November 2015, at which point it was in quite poor condition. -

III. RAPHAEL (1483-1520) Biographical and Background Information 1. Raffaello Santi Born in Urbino, Then a Small but Important C

III. RAPHAEL (1483-1520) Biographical and background information 1. Raffaello Santi born in Urbino, then a small but important cultural center of the Italian Renaissance; trained by his father, Giovanni Santi. 2. Influenced by Perugino, Leonardo da Vinci, and Michelangelo; worked in Florence 1504-08, in Rome 1508-20, where his chief patrons were Popes Julius II and Leo X. 3. Pictorial structures and concepts: the picture plane, linear and atmospheric perspective, foreshortening, chiaroscuro, contrapposto. 4. Painting media a. Tempera (egg binder and pigment) or oil (usually linseed oil as binder); support: wood panel (prepared with gesso ground) or canvas. b. Fresco (painting on wet plaster); cartoon, pouncing, giornata. Selected works 5. Religious subjects a. Marriage of the Virgin (“Spozalizio”), 1504 (oil on roundheaded panel, 5’7” x 3’10”, Pinacoteca de Brera, Milan) b. Madonna of the Meadow, c. 1505 (oil on panel, 44.5” x 34.6”, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) c. Madonna del Cardellino (“Madonna of the Goldfinch”), 1506 (oil on panel, 3’5” x 2’5”, Uffizi Gallery, Florence) d. Virgin and Child with St. Sixtus and St. Barbara (“Sistine Madonna”), 1512-13 (oil on canvas, 8’8” x 6’5”, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden) 6. Portraits a. Agnolo Doni, c.1506 (oil on panel, 2’ ¾” x 1’5 ¾”, Pitti Palace, Florence) b. Maddalena Doni, c.1506 (oil on panel, 2’ ¾” x 1’5 ¾”, Pitti Palace, Florence) c. Cardinal Tommaso Inghirami, c. 1510-14 (oil on panel, 2’11 ¼” x 2’, Pitti Palace, Florence) d. Baldassare Castiglione, c. 1514-15 (oil on canvas, 2’8” x 2’2”, Louvre Museum, Paris) e. -

The Holy Family with Saint Elizabeth

The Holy Family with Saint Elizabeth, the Child Saint John the Baptist and Two Angels, a copy of Raphael Technical report, restoration and new light on its history and attribution José de la Fuente Martínez José Luis Merino Gorospe Rocío Salas Almela Ana Sánchez-Lassa de los Santos This text is published under an international Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Creative Commons licence (BY-NC-ND), version 4.0. It may therefore be circulated, copied and reproduced (with no alteration to the contents), but for educational and research purposes only and always citing its author and provenance. It may not be used commercially. View the terms and conditions of this licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncnd/4.0/legalcode Using and copying images are prohibited unless expressly authorised by the owners of the photographs and/or copyright of the works. © of the texts: Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao Photography credits © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao: figs. 1, 2 and 5-19 © Groeningemuseum, Brugge: fig. 21 © Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistique, Bruxelles: fig. 20 © Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid: fig. 55 © RMN / Gérard Blot-Jean Schormans: fig. 3 © RMN / René-Gabriel Ojéda: fig. 4 Text published in: B’06 : Buletina = Boletín = Bulletin. Bilbao : Bilboko Arte Eder Museoa = Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao = Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, no. 2, 2007, pp. 17-64. Sponsored by: 2 fter undergoing a painstaking restoration process, which included the production of a detailed tech- nical report, the Holy Family with Saint Elizabeth, the Child Saint John the Baptist and Two Angels1 A[fig. -

Leonardo Da Vinci and the Persistence of Myth Emily Hanson

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2012 Inventing the Sculptor: Leonardo da Vinci and the Persistence of Myth Emily Hanson Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Hanson, Emily, "Inventing the Sculptor: Leonardo da Vinci and the Persistence of Myth" (2012). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 765. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/765 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Department of Art History & Archaeology INVENTING THE SCULPTOR LEONARDO DA VINCI AND THE PERSISTENCE OF MYTH by Emily Jean Hanson A thesis presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 2012 Saint Louis, Missouri ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wouldn’t be here without the help and encouragement of all the following people. Many thanks to all my friends: art historians, artists, and otherwise, near and far, who have sustained me over countless meals, phone calls, and cappuccini. My sincere gratitude extends to Dr. Wallace for his wise words of guidance, careful attention to my work, and impressive example. I would like to thank Campobello for being a wonderful mentor and friend, and for letting me persuade her to drive the nearly ten hours to Syracuse for my first conference, which convinced me that this is the best job in the world. -

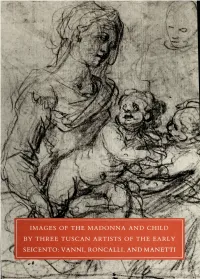

IMAGES of the MADONNA and CHILD by THREE TUSCAN ARTISTS of the EARLY SEICENTO: VANNI, RONCALLI, and MANETTI Digitized by Tine Internet Arcliive

r.^/'v/\/ f^jf ,:\J^<^^ 'Jftf IMAGES OF THE MADONNA AND CHILD BY THREE TUSCAN ARTISTS OF THE EARLY SEICENTO: VANNI, RONCALLI, AND MANETTI Digitized by tine Internet Arcliive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/innagesofmadonnacOObowd OCCASIONAL PAPERS III Images of the Madonna and Child by Three Tuscan Artists of the Early Seicento: Vanni, Roncalli, and Manetti SUSAN E. WEGNER BOWDOIN COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART BRUNSWICK, MAINE Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 86-070511 ISBN 0-91660(>-10-4 Copyright © 1986 by the President and Trustees of Bowdoin College All rights reserved Designed by Stephen Harvard Printed by Meriden-Stinehour Press Meriden, Connecticut, and Lunenburg, Vermont , Foreword The Occasional Papers of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art began in 1972 as the reincarnation of the Bulletin, a quarterly published between 1960 and 1963 which in- cluded articles about objects in the museum's collections. The first issue ofthe Occasional Papers was "The Walker Art Building Murals" by Richard V. West, then director of the museum. A second issue, "The Bowdoin Sculpture of St. John Nepomuk" by Zdenka Volavka, appeared in 1975. In this issue, Susan E. Wegner, assistant professor of art history at Bowdoin, discusses three drawings from the museum's permanent collection, all by seventeenth- century Tuscan artists. Her analysis of the style, history, and content of these three sheets adds enormously to our understanding of their origins and their interconnec- tions. Professor Wegner has given very generously of her time and knowledge in the research, writing, and editing of this article. Special recognition must also go to Susan L. -

The Marian Philatelist, Whole No. 41

University of Dayton eCommons The Marian Philatelist Marian Library Special Collections 3-1-1969 The Marian Philatelist, Whole No. 41 A. S. Horn W. J. Hoffman Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_marian_philatelist Recommended Citation Horn, A. S. and Hoffman, W. J., "The Marian Philatelist, Whole No. 41" (1969). The Marian Philatelist. 41. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_marian_philatelist/41 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Special Collections at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Marian Philatelist by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Marian Philatelist PUBLISHED BY THE MARIAN PHILATELIC STUDY GROUP Business Address: Rev. A. S. Horn Chairman 424 West Crystal View Avenue W. J. Hoffman Editor Orange, California 92667, U.S.A. Vol. 7 No. 2 Whole No. 41 MARCH 1, 1969 NEW ISSUES The original, 46-1/2 inches in diameter, is •in the Uffizi, Florence. Portion of this AJMAN: Set of 5 airmail values, with imperf work seen on the 5 Fr. value in Burundi’s sheet, designated as a "Madonna Set," released 1968 Christmas issue; see article on page November 25, 1968. Ajman is on the "tread with caution list." The designs as follows: 30 Dh. (Class 1) - MADONNA OF THE MILK (Madonna del Latte), by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, active 1319- 1348. Original is in the Church of San Frances co, Siena, Italy. 70 Dh. (Class 1) - SISTINE MADONNA by Raphael. Entire painting is seen on the December 1955 is sue of German Democratic Republic (Scott 277); detail of Madonna and Child on the May 1967 iss ue of Ecuador (see article on page 68, September 1, 1967 issue); same detail on the August 1954 issue of Saar (Scott 251) . -

Santa Maria Del Popolo Piazza Del Popolo Metro Station: Flaminio, Line a 7 AM – 12 PM (Closed Sunday) 4 PM – 7 PM (Closed Sunday)

Santa Maria del Popolo Piazza del Popolo Metro station: Flaminio, line A 7 AM – 12 PM (Closed Sunday) 4 PM – 7 PM (Closed Sunday) Sculpture of Habakkuk and the Angel by Bernini (after 1652) in the Chigi Chapel Crucifixion of St. Peter (1600-01) by Caravaggio in the Cerasi Chapel. Baroque facade added by Bernini in 1600 Standing on the Piazza del Popolo, near the northern gate of the Aurelian Wall, the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo is a small temple with a splendid Renaissance decoration in its interior. In its interior Santa Maria del Popolo’s decoration is unlike any other church in Rome. The ceiling, less high than most built during the same period, is practically bare, while the decoration of each of the small chapels is especially remarkable. Among the beautiful art work found in the church, it is worth highlighting the Chapel Cerasi, which houses two canvases by Caravaggio from 1600, and the Chapel Chigi, built and decorated by Raphael. If you look closely at the wooden benches, you’ll be able to see inscriptions with the names of the people the benches are dedicated to. This custom is also found in a lot of English speaking countries like Scotland or Edinburgh, where the families of the person deceased buy urban furniture in their honour. ******************************************** Located next to the northern gate of Rome on the elegant Piazza del Popolo, the 15th-century Santa Maria del Popolo is famed for its wealth of Renaissance art. Its walls and ceilings are decorated with paintings by some of the greatest artists ever to work in Rome: Pinturicchio, Raphael, Carracci, Caravaggio and Bernini. -

Two Raphael Paintings Unearthed at the Vatican After 500 Years Published 14Th December 2017

AiA Art News-service Two Raphael paintings unearthed at the Vatican after 500 years Published 14th December 2017 Two Raphael paintings unearthed at the Vatican after 500 years Written byDelia Gallagher, CNN A 500-year-old mystery at the Vatican has just been solved. Two paintings by Renaissance master Raphael were discovered during the cleaning and restoration of a room inside the Vatican Museums. Experts believe they are his last works before an early death, around the age of 37, in 1520: "It's an amazing feeling," said the Vatican's chief restorer for the project, Fabio Piacentini. What makes Wallonia unique? "Knowing these were probably the last things he painted, you almost feel the real presence of the maestro." The two female figures, one depicting Justice and the other Friendship, were painted by Raphael around the year 1519, but he died before he could finish the rest of the room. After his death, other artists finished the wall and Raphael's two paintings were forgotten. The clues In 1508, Raphael was commissioned by Pope Julius II to paint the his private apartments. The artist completed three rooms, known today as the "Raphael rooms," with famous frescoes like the School of Athens. He then began plans for the fourth room, the largest in the apartment, a banquet hall called the Hall of Constantine. His plan was to paint the room using oil, rather than the traditional fresco technique. An ancient book from 1550 by Giorgio Vasari, "Lives of the most excellent painters, sculptors and architects," attests that Raphael began work on two figures in a new experiment with oil. -

Power and Nostalgia in Eras of Cultural Rebirth: the Timeless

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2013 Power and Nostalgia in Eras of Cultural Rebirth: The imelesT s Allure of the Farnese Antinous Kathleen LaManna Scripps College Recommended Citation LaManna, Kathleen, "Power and Nostalgia in Eras of Cultural Rebirth: The imeT less Allure of the Farnese Antinous" (2013). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 176. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/176 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POWER AND NOSTALGIA IN ERAS OF CULTURAL REBIRTH: THE TIMELESS ALLURE OF THE FARNESE ANTINOUS by KATHLEEN ROSE LaMANNA SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR MICHELLE BERENFELD PROFESSOR GEORGE GORSE MAY 3, 2013 Acknowledgements To Professor Rankaitis for making sure I could attend the college of my dreams and for everything else. I owe you so much. To Professor Novy for encouraging me to pursue writing. Your class changed my life. Don’t stop rockin! To Professor Emerick for telling me to be an Art History major. To Professor Pohl for your kind words of encouragement, three great semesters, and for being the only person in the world who might love Gladiator more than I do! To Professor Coats for being a great advisor and always being around to sign my many petition forms and for allowing me to pursue a degree with honors. -

Rome Celebrates Raphael Superstar | Epicurean Traveler

Rome Celebrates Raphael Superstar | Epicurean Traveler https://epicurean-traveler.com/rome-celebrates-raphael-superstar/?... U a Rome Celebrates Raphael Superstar by Lucy Gordan | Travel | 0 comments Self-portrait of Raphael with an unknown friend This year the world is celebrating the 500th anniversary of Raphael’s death with exhibitions in London at both the National Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum, in Paris at the Louvre, and in Washington D.C. at the National Gallery. However, the mega-show, to end all shows, is “Raffaello 1520-1483” which opened on March 5th and is on until June 2 in Rome, where Raphael lived the last 12 years of his short life. Since January 7th over 70,000 advance tickets sales from all over the world have been sold and so far there have been no cancellations in spite of coronavirus. Not only is Rome an appropriate location, but so are the Quirinal’s scuderie or stables, as the Quirinal was the summer palace of the popes, then the home of Italy’s Royal family and now of its President. On display are 240 works-of-art; 120 of them (including the Tapestry of The Sacrifice of Lystra based on his cartoons and his letter to Medici-born Pope Leo X (reign 1513-21) about the importance of preserving Rome’s antiquities) are by Raphael himself. Twenty- 1 of 9 3/6/20, 3:54 PM Rome Celebrates Raphael Superstar | Epicurean Traveler https://epicurean-traveler.com/rome-celebrates-raphael-superstar/?... seven of these are paintings, the others mostly drawings. Never before have so many works by Raphael been displayed in a single exhibition.