A Jester's Guide to Creative See[K]Ing Across Disciplines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Deacon As Wise Fool: a Pastoral Persona for the Diaconate

ATR/100.4 The Deacon as Wise Fool: A Pastoral Persona for the Diaconate Kevin J. McGrane* Deacons often sit with the hurt and marginalized. It is in keeping with our ordination vows as deacons in the Episcopal Church, which say, “God now calls you to a special ministry of servanthood. You are to serve all people, particularly the poor, the weak, the sick, and the lonely.”1 Ever task focused, deacons look for the tangible and concrete things we can do to respond to the needs of the least of Jesus’ broth- ers and sisters (Matt. 25:40). But once the food is served, the money given, the medicine dispensed, then what? The material needs are supplied, but the hurt and the trauma are still very much present. What kind of pastoral care can deacons bring that will respond to the needs of the hurting and traumatized? I suggest that, if we as deacons are going to be sources of contin- ued pastoral care beyond being simple providers of material needs, we need to look to the pastoral model of the wise fool for guidance. With some exceptions here and there, deacons are uniquely fit to practice the pastoral persona of the wise fool. The wise fool is a clinical pastoral persona most identified and de- veloped by the pastoral theologians Alastair V. Campbell and Donald Capps. The fool is an archetype in human culture that both Campbell and Capps view as someone capable of rendering pastoral care. In his essay “The Wise Fool,”2 Campbell describes the fool as a “necessary figure” to counterpoint human arrogance, pomposity, and despo- tism: “His unruly behavior questions the limits of order; his ‘crazy’ outspoken talk probes the meaning of ‘common sense’; his uncon- ventional appearance exposes the pride and vanity of those around * Kevin J. -

Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation in the Intermountain Region Part 1

United States Department of Agriculture Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation in the Intermountain Region Part 1 Forest Rocky Mountain General Technical Report Service Research Station RMRS-GTR-375 April 2018 Halofsky, Jessica E.; Peterson, David L.; Ho, Joanne J.; Little, Natalie, J.; Joyce, Linda A., eds. 2018. Climate change vulnerability and adaptation in the Intermountain Region. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-375. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Part 1. pp. 1–197. Abstract The Intermountain Adaptation Partnership (IAP) identified climate change issues relevant to resource management on Federal lands in Nevada, Utah, southern Idaho, eastern California, and western Wyoming, and developed solutions intended to minimize negative effects of climate change and facilitate transition of diverse ecosystems to a warmer climate. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service scientists, Federal resource managers, and stakeholders collaborated over a 2-year period to conduct a state-of-science climate change vulnerability assessment and develop adaptation options for Federal lands. The vulnerability assessment emphasized key resource areas— water, fisheries, vegetation and disturbance, wildlife, recreation, infrastructure, cultural heritage, and ecosystem services—regarded as the most important for ecosystems and human communities. The earliest and most profound effects of climate change are expected for water resources, the result of declining snowpacks causing higher peak winter -

The Evolution of Animal Play, Emotions, and Social Morality: on Science, Theology, Spirituality, Personhood, and Love

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 12-2001 The Evolution of Animal Play, Emotions, and Social Morality: On Science, Theology, Spirituality, Personhood, and Love Marc Bekoff University of Colorado Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_sata Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Behavior and Ethology Commons, and the Comparative Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Bekoff, M. (2001). The evolution of animal play, emotions, and social morality: on science, theology, spirituality, personhood, and love. Zygon®, 36(4), 615-655. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Evolution of Animal Play, Emotions, and Social Morality: On Science, Theology, Spirituality, Personhood, and Love Marc Bekoff University of Colorado KEYWORDS animal emotions, animal play, biocentric anthropomorphism, critical anthropomorphism, personhood, social morality, spirituality ABSTRACT My essay first takes me into the arena in which science, spirituality, and theology meet. I comment on the enterprise of science and how scientists could well benefit from reciprocal interactions with theologians and religious leaders. Next, I discuss the evolution of social morality and the ways in which various aspects of social play behavior relate to the notion of “behaving fairly.” The contributions of spiritual and religious perspectives are important in our coming to a fuller understanding of the evolution of morality. I go on to discuss animal emotions, the concept of personhood, and how our special relationships with other animals, especially the companions with whom we share our homes, help us to define our place in nature, our humanness. -

Psychoethological Perspective on Play: Implications for Research and Practice

Psicologia USP http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0103-656420160122 358 Brincar na perspectiva psicoetológica: implicações para pesquisa e prática Emma Otta* Universidade de São Paulo, Instituto de Psicologia, Departamento de Psicologia Experimental. São Paulo, SP, Brasil Resumo: Este ensaio trata do brincar a partir da perspectiva psicoetológica e examina implicações para a pesquisa e a prática. Ao longo das últimas décadas, crianças vêm ganhando oportunidades de escolarização e atividades dirigidas por adultos, mas perdendo oportunidades de brincadeira livre autogerenciada. Isto é preocupante, considerando as indicações de modelos animais de que a brincadeira social autogerenciada é importante para o desenvolvimento do cérebro social e da capacidade de autorregulação de emoções. Este estudo representa um convite-justificativa para que as crianças recuperem oportunidades de brincadeira natural das quais vêm sendo privadas. Quanto mais conhecermos sobre o brincar, mais adequados seremos nas oportunidades que poderemos oferecer a elas. Precisamos de mais pesquisa sobre este tema na academia, num ambiente intelectual que facilite a colaboração entre etólogos, psicólogos, educadores e neurocientistas, promovendo interação bidirecional entre teoria e prática. Palavras-chave: brincar, cérebro social, desenvolvimento, emoções, natureza. Introdução A razão da etóloga, fascinada pela observação do comportamento Este ensaio trata do brincar a partir da perspectiva psicoetológica e examina as implicações desta Por que convidar a estudar o comportamento de abordagem para pesquisa e prática relativas a um tema brincar dos animais? A resposta mais simples que poderia que considero negligenciado na área acadêmica. O termo dar é o fascínio pela observação do comportamento “abordagem psicoetológica” foi cunhado por Walter espontâneo, livre de limites artificiais. -

Class Clown and Court Jester: a Case Study Approach to the Tradition of the Fool

CLASS CLOWN AND COURT JESTER: A CASE STUDY APPROACH TO THE TRADITION OF THE FOOL By DAVID CHEVREAU B.A., York University, 1979 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Counselling Psychology We accept this Thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1994 © David Chevreau, 1994 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of (jOO^fr^fr ^SfObL^y The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date Apm- ^ 1*T^ DE-6 (2/88) -ii- ABSTRACT Though he is well known, the Class Clown is not particularly well understood. With the exception of one quantitative study by Damingo and Purkey (1978), no significant research has been written on this witty character. The educational community has viewed the Class Clown by and large as an under-achieving student who, in his efforts to get attention, is a disruptive force in the classroom. As such, his behaviour, though often enormously funny, is a threat to the conformity and stability that good classroom discipline demands. -

The Inevitability of Evolutionary Psychology and the Limitations of Adaptationism: Lessons from the Other Primates

International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 2001, 14, 25-42. Copyright 2001 by the International Society for Comparative Psychology The Inevitability of Evolutionary Psychology and the Limitations of Adaptationism: Lessons from the other Primates Frans B. M. de Waal Emory University, U.S.A. The arrival of Evolutionary Psychology (EP) has upset many psychologists. Partly, this reflects resistance to what is perceived as genetic reductionism, partly worry about yet another step closer to the life sciences. Are the life sciences going to devour the social sciences? This essay starts out with a list of pitfalls for the beginning Darwinists that many EP followers are, warning against simplistic adptationist scenarios, and the frag- mentation of the organism, the human brain (a module for every capacity), and the ge- nome (a gene for this and a gene for that). Despite these criticisms, the author is generally sympathetic to the evolutionary approach, however, and feels that EP is inevitable. It may show growing pains, but psychology does need to move under the evolutionary umbrella, which is the only framework that can provide coherence to a fragmented discipline. The essay concludes with several illustrations of the usefulness of evolutionary theory to ex- plain the social behavior of primates. Primatologists face many of the same dilemmas as followers of EP in that primate behavior seems almost endlessly variable. Examples of political strategy, peacemaking, and reciprocal exchange show the complexity, the pro- found similarity to human behavior, and the promise of the evolutionary framework. I am honored and pleased to address psychologists at their annual conven- tion. -

The Value of Using an Evolutionary Framework for Gauging Children's

In Narvaez, D., Panksepp, J., Schore, A., & Gleason, T. (Eds.) (2013). Evolution, Early Experience and Human Development: From Research to Practice and Policy. New York: Oxford University Press. The Value of Using an Evolutionary Framework for Gauging Children’s Well-Being Darcia Narvaez, Jaak Panksepp, Allan Schore, and Tracy Gleason Earlier conceptions of the essential nature of developmental experiences found axiomatic that “early childhood is destiny.” This view was deeply embedded in two paradigms—psychoanalysis under the Freudian view, which emphasized parenting influences, and behaviorism, which emphasized early conditioning and reinforcement history (although both psychoanalytic psychotherapists and behaviorists assumed that patterns could be unlearned with some effort). When developmental psychology changed in paradigm to an ecological system perspective that acknowledges multiple levels of influence (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), emphasis shifted to a focus on human resiliency in the face of risk factors (Lester, Masten, & McEwen, 2007). Neuroscience has bolstered the resilient view of development with evidence that the brain remains plastic throughout the life span (e.g., Doidge, 2007; Merzenich et al., 1996). Early childhood is thus viewed within the prism of lifelong interactions among ecosystems and individual neuro- affective propensities, highlighting developmental person-by-context interactions and abundant individual variability in emotional resilience (Suomi, 2006; Worthman, Plotsky, Schechter, & Cummings, 2010). In the enthusiasm to embrace ideas of life span resiliency, psychology has often soft- pedaled the lasting neurobiological influences of early childhood experience. When researchers have documented the remarkable resiliency of children (e.g., Lester et al., 2007), they often point to better outcomes than might be predicted from certain preclinical studies of early - i - developmental trajectories (Kagan, 1997). -

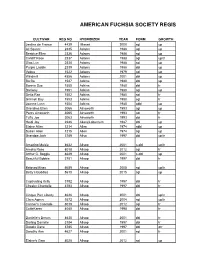

Regn Lst 1948 to 2020.Xls

AMERICAN FUCHSIA SOCIETY REGISTERED FUCHSIAS, 1948 - 2020 CULTIVAR REG NO HYBRIDIZER YEAR FORM GROWTH Jardins de France 4439 Massé 2000 sgl up All Square 2335 Adams 1988 sgl up Beatrice Ellen 2336 Adams 1988 sgl up Cardiff Rose 2337 Adams 1988 sgl up/tr Glas Lyn 2338 Adams 1988 sgl up Purple Laddie 2339 Adams 1988 dbl up Velma 1522 Adams 1979 sgl up Windmill 4556 Adams 2001 dbl up Bo Bo 1587 Adkins 1980 dbl up Bonnie Sue 1550 Adkins 1980 dbl tr Dariway 1551 Adkins 1980 sgl up Delta Rae 1552 Adkins 1980 sgl tr Grinnell Bay 1553 Adkins 1980 sgl tr Joanne Lynn 1554 Adkins 1980 sdbl up Grandma Ellen 3066 Ainsworth 1993 sgl up Percy Ainsworth 3065 Ainsworth 1993 sgl tr Tufty Joe 3063 Ainsworth 1993 dbl tr Heidi Joy 2246 Akers/Laburnum 1987 dbl up Elaine Allen 1214 Allen 1974 sdbl up Susan Allen 1215 Allen 1974 sgl up Grandpa Jack 3789 Allso 1997 dbl up/tr Amazing Maisie 4632 Allsop 2001 s-dbl up/tr Amelia Rose 8018 Allsop 2012 sgl tr Arthur C. Boggis 4629 Allsop 2001 s-dbl up Beautiful Bobbie 3781 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Beloved Brian 5689 Allsop 2005 sgl up/tr Betty’s Buddies 8610 Allsop 2015 sgl up Captivating Kelly 3782 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Cheeky Chantelle 3783 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Cinque Port Liberty 4626 Allsop 2001 dbl up/tr Clara Agnes 5572 Allsop 2004 sgl up/tr Conner's Cascade 8019 Allsop 2012 sgl tr CutieKaren 4040 Allsop 1998 dbl tr Danielle’s Dream 4630 Allsop 2001 dbl tr Darling Danielle 3784 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Doodie Dane 3785 Allsop 1997 dbl gtr Dorothy Ann 4627 Allsop 2001 sgl tr Elaine's Gem 8020 Allsop 2012 sgl up Generous Jean 4813 -

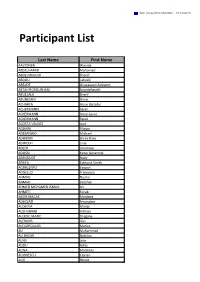

Participant List

Ref. Ares(2015)5922007 - 17/12/2015 Participant List Last Name First Name AALTONEN Wanida ABDELHAMID Mohamed ABDELMEGUID Sheref ABDOU Lahadji ABEJIDE Oluwaseun Adeyemi ABTAHIFOROUSHANI Seyedehasieh ABUELALA Sherif ABUNEMEH Omar ACHARYA Arjun Bahadur ACHERMANN Sarah ACKERMANN Anne-Laure ACKERMANN Raoul ACOSTA VALDEZ Jose ADDARII Filippo ADESANWO Michael ADHIKARI Shree Ram ADINOLFI Livia ADLER Jéromine ADOSSI Yawo Nevemde AERNOUDT Rudy AFRIFA Edmund Smith AGBALENYO Yawovi AGNELLO Francesca AHMAD Najma AHMAD Zeeshan AHMED MOHAMED ISMAIL Ali AHMETI Korab AKSIN MACAK Marijana ALBIZZATI Amandine ALCHEVA Marija ALDHUBAIBI Hitham ALEKSIC MATIC Dragana ALEXAKIS Ilias ALEXOPOULOS Marios ALI Muhammad ALI BACAR Nabilou ALIAS Jose ALIDU Adilu ALINA Marinoiu ALIONESCU Ciprian ALIX Nicole ALLET Marion ALMAZYAN Lida ALMEIDA Katia ALONSO Beatriz ALSAWALAH Abedallah ALTINOK Salih ALVARADO TANAMACHI Sayuri ALVAREZ Ana ALVES Filipe AMADIO Nicolas AMALFITANO Marie AMAZIT Anaïs AMBROSIO Giuseppe AMET Suzon AMITSIS Gabriel ANASTOPOULOS Konstantinos ANCA Gunta ANCEL Florian ANDRES Rodolphe ANDREU Tomás ANDREW Mwebaza ANDRICOPOULOU Anna ANDRIOT Patricia ANDRITSOU Anastasia ANESE Tobia ANGELOVA Milena ANNE Leautier ANSELM Cecile APOLLONI Guglielmo APOSTOLIDIS Catherine APPEL Ulrik ARNOLD David AROYAN Luciné ARREGUI Karin Arriaga Sierra Hermes ARROYO DE SANDE Carmen ARVANITI Chrysafo ASCHARI-LINCOLN Jessica ASLAN Ayse ASRAF Adeeba ASSABA Inès ATAMAN SCHARNING Ayşegül ATAYI Ayoko Veronique ATHANASIADOU Natasha Marie AUCONIE Sophie AUGER Christophe AVENTAGGIATO Giovanni -

Till Eulenspiegel As a “Recurring Character” in the Works of Hans Sachs

Narrative Arrangement in 16th-Century Till Eulenspiegel Texts: The Reinvention of Familiar Structures A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Isaac Smith Schendel IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advisor: Dr. Anatoly Liberman June 2018 © Isaac Smith Schendel 2018 i Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral advisor, Dr. Anatoly Liberman, for his kind direction, ideas, and guidance through the entire process of graduate school, from the first lectures on Middle High German grammar and Scandinavian Literature, to the preliminary exams, prospectus and multiple thesis drafts. Without his watchful eye, advice, and inexhaustible patience, this dissertation would have never seen the light of day. Drs. James A. Parente, Andrew Scheil, and Ray Wakefield also deserve thanks for their willingness to serve on the committee. Special gratitude goes to Dr. Parente for reading suggestions and leadership during the latter part of my graduate school career. His practical approach, willingness to meet with me on multiple occasions, and ability to explain the intricacies of the university system are deeply appreciated. I have also been helped by a number of scholars outside of Minnesota. The material discussed in the second chapter of the dissertation is a reformulated, expanded, and improved version of my article appearing in Daphnis 43.2. Although the central thesis is now radically different, I would still like to thank Drs. Ulrich Seelbach and Alexander Schwarz for their editorial work during that time, especially as they directed my attention to additional information and material within the S1515 chapbook. -

Art and Emotion: the Variety of Aesthetic Emotions and Their Internal Dynamics

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology 20, 2020 @PTPN Poznań 2020, DOI 10.14746/ism.2020.20.5 Piotr PrzybYSZ https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8184-3656 Faculty of Philosophy, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Art and Emotion: the variety of Aesthetic Emotions and their Internal Dynamics AbSTRACT: The aim of this paper is to propose an interpretation of aesthetic emotions in which they are treated as various affective reactions to a work of art. I present arguments that there are three different types of such aesthetic emotional responses to art, i.e., embodied emotions, epistemic emotions and contextual-associative emotions. I then argue that aesthetic emotions understood in this way are dynamic wholes that need to be explained by capturing and describing their internal temporal dynamics as well as by analyzing the relationships with the other components of aesthetic experience. Keywords: aesthetic emotions, aesthetic experience, art, music, neuroaesthetics Introduction There is no doubt that music, as well as other genres of art such as painting, is a reliable means of eliciting various emotional reactions. Exposure to a song or painting may result in feelings such as being touched or elated. beha- vioral reactions such as chills or tears may also appear in reaction to the work of art. In other situations, music or painting may serve to calm someone or can be used to improve one’s mood. Despite the unquestionable ability of art to evoke emotions, this ability is still not properly understood, and philosophers and re- searchers are constantly trying to explain it. The tradition of speculative inquiry and empirical studies concerning aes- thetic emotions is, naturally, very long. -

Project Summer Read 2020

Project SUMMER Read 2020 SUMMER READING SUGGESTIONS AND RESOURCES SUGERENCIAS DE LECTURE VERANO Y RECURSOS Elementary K-5 www.whiteplainspublicschools.org/read Parent Resources Recursos Para Padres Choosing Books for Children by Betsy Hearne Best of the Best for Children by Denise Perry Donavin, ed. The New Read‐Aloud Handbook by Jim Trelease For Reading Out Loud by Margaret May Kimmel Read to Me: Raising Kids Who Love to Read by Bernice E. Cullinan Parent’s Guide to the Best Books for Children by Eden Ross Lipson Reading Magic by Mem Fox Other Websites Otros sitios web White Plains Public Schools whiteplainspublicschools.org Westchester Libraries Online westchesterlibraries.org White Plains Public Library whiteplainslibrary.org White Plains Youth Bureau whiteplainsyouthbureau.org Barnes & Noble Booksellers barnesandnoble.com Common Sense Media commonsensemedia.org 2020 www.whiteplainspublicschools.org/read WHITE PLAINS PUBLIC SCHOOLS EDUCATION HOUSE FIVE HOMESIDE LANE WHITE PLAINS, NEW YORK 10605 914-422-2000 www.wpcsd.k12.ny.us Joseph L. Ricca, Ed.D. Superintendent of Schools June 2020 Dear Parent/Guardian, Many parents ask: “What can I do to help my child be a better student?” The key to a good education is reading with understanding. If you encourage your child to read, if you read to your child, if you discuss with your child what is being read, your child will develop a love for reading and learning. Reading is both fun and useful. Folktales, sports news, fashion news, business news, celebrity gossip, and comics –it all has value. Our Project Summer Read program is designed to make it easier to select books, for a full summer of reading.