The Art of Community Seven Principles for Belonging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies –

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan Published by Self Improvement Online, Inc. http://www.SelfGrowth.com 20 Arie Drive, Marlboro, NJ 07746 ©Copyright by David Riklan Manufactured in the United States No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Limit of Liability / Disclaimer of Warranty: While the authors have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents and specifically disclaim any implied warranties. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. The author shall not be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Spiritual Cinema 8 About SelfGrowth.com 10 Newer Inspirational Movies 11 Ranking Movie Title # 1 It’s a Wonderful Life 13 # 2 Forrest Gump 16 # 3 Field of Dreams 19 # 4 Rudy 22 # 5 Rocky 24 # 6 Chariots of -

3Fjowfoujoh $Mbttjdt

THE TM 911 Franklin Street Weekly Newspaper Michigan City, IN 46360 Volume 36, Number 3 Thursday, January 23, 2020 3FJOWFOUJOH$MBTTJDT by Edmund Lawler Dan Schaaf (right) records dialogue for his latest project, “Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler,” with Sherri Waddle-Cummings. Photos by Paul Kemiel Suddenly, quite by accident, Dan Schaaf discov- ered a wildly creative artistic pursuit — breathing new life into classic silent fi lms by composing musi- cal scores and scripting dialogue performed by local stage actors. “Channel 20 used to run silent fi lms at midnight,” Schaaf recalls of his epiphany in the late 1990s. “They ran the Fritz Lang classic ‘Metropolis,’ a 1927 sci-fi that I had never seen. I fi gured I needed to see it once in my life, so I set the VCR to record it at midnight.” He watched it the next morning and was enchant- ed by the epic work of cinema from the legendary German director. But there was one problem. “It had this dreadful musical score that sounded like it came from a Laurel and Hardy comedy, and it had absolutely nothing to do with the fi lm,” Schaaf says. “I told myself, ‘I can do better than this.’” And he did. Schaaf, who fi rst began composing music as a Marquette High School student and later while studying English and electrical engineering at Pur- due University, penned a score for “Metropolis.” Un- Sherri Waddle-Cummings infuses emotion into her dialogue for the fi lm. Continued on Page 2 THE Page 2 January 23, 2020 THE 911 Franklin Street • Michigan City, IN 46360 219/879-0088 • FAX 219/879-8070 Beacher Company Directory -

1-22-21 Tribune/Sentinel.Indd

6 TTribune/Sentinelribune/Sentinel EEntertainmentntertainment FFriday,riday, JJanuaryanuary 22,22, 22021021 ‘Cobra Kai’ never dies: Q&A with stars of Netfl ix series Left: “Cobra Kai” features original “The Karate Kid” stars Ralph Macchio, left, as Daniel LaRusso, and William Zabka as Johnny Lawrence. (Cr. Curtis Bonds Baker/Netfl ix © 2020) • Middle: Samantha LaRusso (Mary Mouser) turns to Daniel to rediscover her strength. • Right: John Kreese (Martin Kove) is back on “Cobra Kai.” (Courtesy of Netfl ix © 2020) BY JOSHUA MALONI issues of yesteryear. campaign to close down Johnny’s lyzed from the waist down. Sam is simple because, walking back onto GM/Managing Editor But now imagine this: In season chop-shop. The two old rivals become shell-shocked and scarred from her the set is usually what just brings it Just like the three tenets scrolled one, Daniel LaRusso (Ralph Mac- new enemies (sometimes frenemies), fi ght with Tory. Johnny has gone on all back all of a sudden. I can have across the dojo wall suggest, “Cobra chio) – sans the deceased Mr. Miyagi each trying to convince California a bender, and Daniel – at Amanda’s several months away from it, and Kai” struck fi rst, struck hard, and (Pat Morita) – has become a little youth theirs is the true karate. request – has ceased teaching karate. then I walk back into the backyard showed no mercy when it debuted on unlikable. No longer an underdog, Of course, in the season fi nale, Kreese, believing he has won, contin- of Mr. Miyagi’s house and it’s like, Netfl ix in 2020. -

A Letter to Daniel Larusso, the Karate Kid Ryan Shoemaker

Booth Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 4 1-24-2014 A Letter to Daniel Larusso, the Karate Kid Ryan Shoemaker Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/booth Recommended Citation Shoemaker, Ryan (2014) "A Letter to Daniel Larusso, the Karate Kid," Booth: Vol. 6: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/booth/vol6/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Booth by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Letter to Daniel Larusso, the Karate Kid Abstract Dear Daniel, Good talking with you at the All-Valley Karate Championships. What a story you have! Inspiring. Seriously. The tus ff movies are made of. Consider me a big fan. I don’t know, maybe I saw something of myself in you, the lanky underdog trying to get his footing in that first match and then finding his stride, fighting, really, for his life and not just some trophy or title. Keywords fiction, karate, California Cover Page Footnote "A Letter to Daniel Larusso, the Karate Kid" was originally published at Booth. This article is available in Booth: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/booth/vol6/iss1/4 Shoemaker: A Letter to Daniel Larusso, the Karate Kid ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! January 24,! 2014! A Letter to Daniel Larusso, the Karate Kid ! by Ryan Shoemaker ! Dear Daniel, ! Good talking with you at the All-Valley Karate Championships. What a story you have! Inspiring. Seriously. The stuff movies are made of. -

New Jersey's Medal of Honor Recipients in the Civil War

NEW JERSEY’S MEDAL OF HONOR RECIPIENTS IN THE CIVIL WAR 1861-1865 By Michael R. Horgan, LTC William H. Kale, USA (Ret), and Joseph Francis Seliga 1 Preface This booklet is a compilation of the panels prepared for an exhibit at the General James A. Garfield Camp No. 4, Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War Museum to commemorate the Sesquicentennial of the Civil War. This museum is co-located with the National Guard Militia Museum of New Jersey in the Armory at 151 Eggerts Crossing Road, Lawrenceville, NJ. Volunteers who work in both museums prepared the exhibit over the past year. The exhibit opened on May 23, 2011, the 150th anniversary of the New Jersey Brigade’s crossing over the Potomac River into the Confederacy on that date in 1861. The two museums are open on Tuesdays and Fridays from 9:30 am to 3:00 pm. Group tours may be scheduled for other hours by leaving a message for the Museum Curator at (609) 530-6802. He will return your call and arrange the tour. Denise Rogers, a former Rider University student intern at the Militia Museum, and Charles W. Cahilly II, a member and Past Commander of the General James A. Garfield Camp No. 4, assisted with research in the preparation of this exhibit. Cover Picture: Medal of Honor awarded to Sergeant William Porter, 1st New Jersey Cavalry Regiment. Photo courtesy of Bob MacAvoy. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM PAGE NO. Title Page 1 Preface 2 Table of Contents 3 The Medal of Honor in the Civil War 4 New Jersey's Civil War Medal of Honor Recipients 5-6 Earning the Medal of Honor 7-8 Counting Medals of Honor 9 Terminology 10-13 The Army Medal of Honor 84 The Navy Medal of Honor 85 Blank Page 86 3 The Medal of Honor in the Civil War An Act of Congress in 1861 established the Medal of Honor to “promote efficiency in the Navy.” President Abraham Lincoln signed it into law on December 21, 1861. -

To Download The

U Inn & Mini Golf ,\_, GI.JEST DIRECTORY Emerold Dolphin lnn 1211 S Moin Street Fort Brogg, CA 95437 707-964-6699 \--l L. I Inn & Mini Golf Welcome Fort Brogg, CA EMERATD DOTPHIN INN l2ll S Moin Street Fort Brogg, CA95437 707-964-6699 We wish to welcome you to the Emerold Dolphin lnn ond to the mojestic Mendocino coost, Pleose enjoy your stoy here ond everything the historic town of Fort Brogg hos to offer you. Whether you qre here for business or pleosure, we wont you to know thot we will do everything we con to moke your visit with us pleosuroble ond reloxing. This guest directory will provide voluoble informotion obout our property's focilities ond services, points of interest, ond o host of services provided by our locol oreo merchonts while you're in the oreo, Thonk you for stoying ot the Emerold Dolphin Inn, We hope the next time you visit the beoutiful city of Fort Brogg, Colifornio you will ogoin choose our property for your occommodotions. Sincerely, Kim Queen Monogement ond Stoff Mendocino County ln-Room Guest Services Directory Inn & Mini Go \,./ Guest lnfo Fort Brogg, CA Copy Service Copies ore ovoiloble ot the Front Desk from 7:00 om - l0:00 pm doily for 25C per poge. Credit Cords For your convenience we occept Viso, Moslercord, Americon Express ond Discover, Cribs A limited number of cribs ore ovoiloble on o first come, first served bosis. Pleose contoct the Froni Desk to request one, A chorge of $.l2 per night will opply, Disobililies Emerold Dolphin lnn is committed to providing occessible focilities for guests with disobilities, lf you encounter borriers during your stoy, pleose contoct the Monoger. -

Aspectos Educacionais Do Karate: Discutindo Suas Representações No Cinema1

SEÇÃO: ARTIGOS Aspectos educacionais do karate: discutindo suas representações no cinema1 Rafael Cava Mori2 ORCID: 0000-0001-6301-2795 Gilmar Araújo de Oliveira3 ORCID: 0000-0002-7617-6235 Resumo O karate é uma luta originária de Okinawa, ilha ao sul do Japão. Historicamente, atravessou três períodos: a partir do século XVII, como bujutsu, técnica clandestina de luta; depois, como budo, quando foi convertido em luta tradicional japonesa, em fins do século XIX, propugnando valores educacionais e identitários; e finalmente, como esporte de luta, quando foi associado a performance motora e competitividade, no século XX. Ao considerar o papel do karate como veiculador de valores de um Japão idealizado – japonesidade –, este trabalho analisa representações cinematográficas dessa luta. A análise focou nos aspectos educativos retratados nos filmes, a série estadunidense The karate kid e o japonês Kuro obi, sendo conduzida conforme três categorias: a relação entre teoria e prática; ruídos e conflitos entre professor e aluno; e formação do aluno como futuro professor. Os resultados revelam que as obras criticam a esportivização do karate, enfatizando a representação de aspectos educacionais associados aos períodos do bujutsu e, principalmente, do budo. Também, colaboram para reafirmar e atualizar a japonesidade, ao tratar os princípios do budo e sua transmissão educacional de forma idealizada, sem aludir a seu caráter moderno. Ainda, os filmes apresentam divergências em relação à proposta contemporânea de uma pedagogia das lutas, fundamentada na ciência da motricidade humana. Por outro lado, as produções cinematográficas contribuem para a área educacional na medida em que possibilitam discussões a respeito dos processos formativos e seus percalços, retratados de forma original, recorrendo aos conceitos de yin/ yang relacionados aos princípios zen -budistas do budo. -

View Stage Descriptions

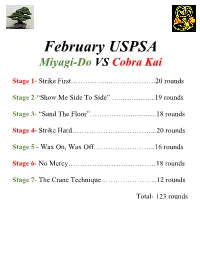

February USPSA Miyagi-Do VS Cobra Kai Stage 1- Strike First……….. …...……………….20 rounds Stage 2-“Show Me Side To Side” …....................19 rounds Stage 3- “Sand The Floor”……………….............18 rounds Stage 4- Strike Hard……………………………...20 rounds Stage 5 - Wax On, Wax Off……………………..16 rounds Stage 6- No Mercy………………………….……18 rounds Stage 7- The Crane Technique…………………...12 rounds Total- 123 rounds LIPSA Strike First Special Thanks: Johnny Lawrence, John Kreese RULES: Practical Shooting Handbook, Latest Edition Course Designer: Michael Linsalata START POSITION: Standing with hands flat on X’s. Gun loaded and holstered. PCC start is gun loaded, safety on. Muzzle touching mark on wall. Butt of gun touching belt. STAGE PROCEDURE SCORING At signal, engage all targets and steel as they SCORING: Comstock, 20 rounds, 100 points become visible from within the fault lines. TARGETS: 6 USPSA, 8 steel Remember, Cobra Kai for life! SCORED HITS: Best 2 per USPSA, Steel Down = 1A START-STOP: Audible-Last Shot P 1-8 T3 T4 T1 T6 T5 T2 X X Soft Cover Soft Cover Stage 1 LIPSA ”Show Me Side To Side” Special Thanks: Miyagi-Do, The Karate Kid RULES: Practical Shooting Handbook, Latest Edition Course Designer: Michael Linsalata START POSITION: Standing with toes touching RED mark, wrists below belt. Gun loaded and holstered. PCC start is gun loaded, safety on. Pointing down range. Butt of gun touching belt. STAGE PROCEDURE SCORING At signal, engage all targets and steel as they SCORING: Comstock, 19 rounds, 95 points become visible from within the fault lines. TARGETS: 7 IPSC, 5 steel Remember, Balance! SCORED HITS: Best 2 per IPSC, Steel Down = 1A START-STOP: Audible-Last Shot SS 1-2 PP 1-3 T2 T3 T4 T5 T6 T1 T7 Stage 2 LIPSA “Sand The Floor” Special Thanks: Miyagi-Do, The Karate Kid RULES: Practical Shooting Handbook, Latest Edition Course Designer: Michael Linsalata START POSITION: Standing directly behind table, wrists above shoulders. -

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Lead Actor In A Comedy Series Tim Allen as Mike Baxter Last Man Standing Brian Jordan Alvarez as Marco Social Distance Anthony Anderson as Andre "Dre" Johnson black-ish Joseph Lee Anderson as Rocky Johnson Young Rock Fred Armisen as Skip Moonbase 8 Iain Armitage as Sheldon Young Sheldon Dylan Baker as Neil Currier Social Distance Asante Blackk as Corey Social Distance Cedric The Entertainer as Calvin Butler The Neighborhood Michael Che as Che That Damn Michael Che Eddie Cibrian as Beau Country Comfort Michael Cimino as Victor Salazar Love, Victor Mike Colter as Ike Social Distance Ted Danson as Mayor Neil Bremer Mr. Mayor Michael Douglas as Sandy Kominsky The Kominsky Method Mike Epps as Bennie Upshaw The Upshaws Ben Feldman as Jonah Superstore Jamie Foxx as Brian Dixon Dad Stop Embarrassing Me! Martin Freeman as Paul Breeders Billy Gardell as Bob Wheeler Bob Hearts Abishola Jeff Garlin as Murray Goldberg The Goldbergs Brian Gleeson as Frank Frank Of Ireland Walton Goggins as Wade The Unicorn John Goodman as Dan Conner The Conners Topher Grace as Tom Hayworth Home Economics Max Greenfield as Dave Johnson The Neighborhood Kadeem Hardison as Bowser Jenkins Teenage Bounty Hunters Kevin Heffernan as Chief Terry McConky Tacoma FD Tim Heidecker as Rook Moonbase 8 Ed Helms as Nathan Rutherford Rutherford Falls Glenn Howerton as Jack Griffin A.P. Bio Gabriel "Fluffy" Iglesias as Gabe Iglesias Mr. Iglesias Cheyenne Jackson as Max Call Me Kat Trevor Jackson as Aaron Jackson grown-ish Kevin James as Kevin Gibson The Crew Adhir Kalyan as Al United States Of Al Steve Lemme as Captain Eddie Penisi Tacoma FD Ron Livingston as Sam Loudermilk Loudermilk Ralph Macchio as Daniel LaRusso Cobra Kai William H. -

Karate Kid | Whistlekickmartialartsradio.Com

Episode 67 – Karate Kid | whistlekickMartialArtsRadio.com Jeremy Lesniak: Hey there, everyone! It's episode 67 of whistlekick martial arts radio. The only place to hear the best conversations about the martial arts like today’s episode all about that classic movie, The Karate Kid. I’m the founder here at whistlekick but I'm better known as your host, Jeremy Lesniak. Whistlekick, in case you don’t know, makes the world’s best sparring gear and some excellent apparel and accessories for practitioners and fans of traditional martial arts. I’d like to welcome our new listeners and thank all of you that are listening again. If you're not familiar with our products, you can learn more about them at whistlekick.com. All of our past podcast episodes, show notes and a lot more are at whistlekickmartialartsradio.com. today’s episode also has a full transcript with lots of photos, videos, links and some other great stuff over on the website. If you're listening from a computer, you might want to follow along with everything we’ve posted there and while you're over at the website, go ahead and sign up for the newsletter. We offer exclusive content to subscribers and it's the only place to find out about upcoming guests. Now, when we talk about martial arts movies, there are a few that immediately come to mind for most people. If you're a martial artist or a fan of the genre, you likely know a lot of them but for those that do not train in the martial arts or are only casually interested in the movies, there's a much shorter list. -

LAAPFF 2015 Catalog

VISUAL COMMUNICATIONS presents the LOS ANGELES ASIAN PACIFIC FILM FESTIVAL APRIL 23 – 30, 2015 No. 31 LITTLE TOKYO _ KOREATOWN _ WEST HOLLYWOOD SEE YOU NEXT YEAR! CONTENTS 7 Festival Welcome 8 Festival Sponsors 10 Community Partners 12 “About VC” Update for 2015 14 Friends of Visual Communications 16 AWC Indiegogo Supporters 18 Year of The Question of the Year! 26 Why Arthur Dong Still Matters 32 Festival Awards: Past Awardees 36 Festival Award Nominees: Feature Narrative 39 Festival Award Nominees: Feature Documentary 42 Festival Award Nominees: Short Film 48 Programmers’ Recommendations 51 Conference for Creative Content 2015 56 Filmmaker Panels & Seminars 60 Program Schedule 61 Box Office Info 62 Venue Info 63 Parties & Afterhours 65 Festival Galas 75 Festival Special Presentations 83 Artist’s Spotlight: Arthur Dong 87 Narrative Competition Films 97 Documentary Competition Films 107 International Showcase Films 123 Short Film Programs 144 Acknowledgements 146 Print & Tape Sources 150 Title/Artist Index 152 Country Index The Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival • 2 The Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival • 3 The Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival • 4 The Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival • 5 The Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival • 6 WELCOME Welcome to the 31st edition of presentations, we are extremely proud to showcase the Los Angeles Asian Pacific returning, seasoned, and emerging Asian Pacific Film Festival! American and International artists and their stories to After a 5-year absence, Visual our communities throughout the Festival at the JACCC, Communications is excited to Japanese American National Museum, Downtown open the Festival at the Japanese Independent, The Great Company, CGV Cinemas, and American Cultural & Community the Directors Guild of America. -

Eugenics and the Holocaust

1 Eugenics and the Holocaust Dr. Karl Brandt – Madison Grant- Wilhelm Oder By Jerry Klinger Grandpa, you told me about the Holocaust. I don’t understand how it could happen? Chandler, I don’t think God does either. William Rabinowitz Ethics is clear if the fogginess of reality does not get in the way. Judith Rice He taught the Polish and Ukrainian volunteers how to kill Jews without feeling, like he did. W. Oder My wife has a first cousin, Simcha. He is a “Black Hat” and a Rosh Yeshivah in Jerusalem. Simcha and his wife Rifkah met us for dinner in Los Angeles. He was on one of his many fund raising trips for the Yeshivah. Simcha hugged me a large warm hello when we met at the restaurant but he would not even shake hands with my wife though she offered. The dinner started pleasantly at first. I guess Simcha wanted to release some angry experience from the day about the disgusting ethics he was finding in America. He brought up the subject of abortion. Simcha launched into a railing burst of anger as he talked about abortionists. 2 “They kill, they murder. Abortionists are the lowest vermin on the earth. The Jewish ones, the Jewish doctors who abort Jewish women, should have their souls cut off from everything, may God curse their names,” he hissed. I sat back and looked at him. The table was quiet after his outburst. Never one to speak loudly, I was easily heard. “Simcha, you know that my family were survivors,” I said looking deep into his eyes.