Simulation of Trace Gas Redistribution by Convective Clouds–Liquid Phase Processes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nitrogen Trace Gas Emissions from a Riparian Ecosystem in Sot&Em

CHEMOSPHERE PERGAMON Chemosphere 49 (2002) 1389-l 398 www.elsevier.com/locate/chemosphere Nitrogen trace gas emissions from a riparian ecosystem in sot&em Appalachia John T. Walker aP*, Christopher D. Geron a, James M. Vose b, Wayne T. Swank b ’ US Enviromental Protection Agency, Natkmal R&k Managmt Research Laboratory, iUD-63, Research Triangk Park, NC 27711, USA b US Department of Agricdture, Forest Service, Coweeta Hydrologic Laboratory, Otto, NC 28763, USA Received 11 July 2001; received in revised form 21 May 2002; accepted 19 June 2002 Abstract In this paper, we present two years of seasonal nitric oxide (NO), ammonia (NH3), and nitrous oxide (NrO) trace gas fluxes measured in a recovering riparian zone with cattle excluded and adjacent riparian zone grazed by cattle. In the recovering riparian zone, average NO, NH3, and NrO fluxes were 5.8,2.0, and 76.7 ngNm-* s-i (1.83,0.63, and 24.19 kg N ha-’ y-t), respectively. Fluxes in the grazed riparian zone were larger, especially for NO and NHr, measuring 9.1, 4.3, and 77.6 ng Nm-* s-* (2.87, 1.35, and 24.50 kg N ha-’ y-l) for NO, NHr, and N20, respectively. On average, NzO accounted for greater than 85% of total trace gas flux in both the recovering and grazed riparian zones, though NrO fluxes were highly variable temporally. In the recovering riparian zone, variability in seasonal average fluxes was ex- plained by variability in soil nitrogen (N) concentrations. Nitric oxide flux was positively correlated with soil ammo- nium (NH:) concentration, while N20 flux was positively correlated with soil nitrate (NO;) concentration. -

Relative Importance of Gas Uptake on Aerosol and Ground Surfaces Characterized by Equivalent Uptake Coefficients

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 10981–11011, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-10981-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Relative importance of gas uptake on aerosol and ground surfaces characterized by equivalent uptake coefficients Meng Li1,a, Hang Su1, Guo Li1, Nan Ma2, Ulrich Pöschl1, and Yafang Cheng1 1Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, Mainz, 55118, Germany 2Center for Air Pollution and Climate Change Research (APCC), Institute for Environmental and Climate Research (ECI), Jinan University, Guangzhou, 511443, China anow at: Chemical Science Division, Earth System Research Laboratory, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Boulder, Colorado 80305, USA Correspondence: Hang Su ([email protected]) and Yafang Cheng ([email protected]) Received: 19 March 2019 – Discussion started: 2 April 2019 Revised: 9 July 2019 – Accepted: 19 July 2019 – Published: 29 August 2019 Abstract. Quantifying the relative importance of gas up- Given the fact that most models have considered the up- take on the ground and aerosol surfaces helps to determine takes of these species on the ground surface, we suggest also which processes should be included in atmospheric chem- considering the following processes in atmospheric models: istry models. Gas uptake by aerosols is often characterized N2O5 uptake by all types of aerosols, HNO3 and SO2 uptake by an effective uptake coefficient (γeff), whereas gas uptake by mineral dust and sea salt aerosols, H2O2 uptake by min- on the ground is usually described by a deposition velocity eral dust, NO2 uptakes by sea salt aerosols and O3 uptake by (Vd). -

Development Team

Paper No: 16 Environmental Chemistry Module: 01 Environmental Concentration Units Development Team Prof. R.K. Kohli Principal Investigator & Prof. V.K. Garg & Prof. Ashok Dhawan Co- Principal Investigator Central University of Punjab, Bathinda Prof. K.S. Gupta Paper Coordinator University of Rajasthan, Jaipur Prof. K.S. Gupta Content Writer University of Rajasthan, Jaipur Content Reviewer Dr. V.K. Garg Central University of Punjab, Bathinda Anchor Institute Central University of Punjab 1 Environmental Chemistry Environmental Environmental Concentration Units Sciences Description of Module Subject Name Environmental Sciences Paper Name Environmental Chemistry Module Name/Title Environmental Concentration Units Module Id EVS/EC-XVI/01 Pre-requisites A basic knowledge of concentration units 1. To define exponents, prefixes and symbols based on SI units 2. To define molarity and molality 3. To define number density and mixing ratio 4. To define parts –per notation by volume Objectives 5. To define parts-per notation by mass by mass 6. To define mass by volume unit for trace gases in air 7. To define mass by volume unit for aqueous media 8. To convert one unit into another Keywords Environmental concentrations, parts- per notations, ppm, ppb, ppt, partial pressure 2 Environmental Chemistry Environmental Environmental Concentration Units Sciences Module 1: Environmental Concentration Units Contents 1. Introduction 2. Exponents 3. Environmental Concentration Units 4. Molarity, mol/L 5. Molality, mol/kg 6. Number Density (n) 7. Mixing Ratio 8. Parts-Per Notation by Volume 9. ppmv, ppbv and pptv 10. Parts-Per Notation by Mass by Mass. 11. Mass by Volume Unit for Trace Gases in Air: Microgram per Cubic Meter, µg/m3 12. -

The Vertical Distribution of Soluble Gases in the Troposphere

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title The vertical distribution of soluble gases in the troposphere Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7gc9g430 Journal Geophysical Research Letters, 2(8) ISSN 0094-8276 Authors Stedman, DH Chameides, WL Cicerone, RJ Publication Date 1975 DOI 10.1029/GL002i008p00333 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Vol. 2 No. 8 GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCHLETTERS August 1975 THE VERTICAL DISTRIBUTION OF SOLUBLE GASES IN THE TROPOSPHERE D. H. Stedman, W. L. Chameides, and R. J. Cicerone Space Physics Research Laboratory Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48105 Abstrg.ct. The thermodynamic properties of sev- Their arg:uments were based on the existence of an eral water-soluble gases are reviewed to determine HC1-H20 d•mer, but we consider the conclusions in- the likely effect of the atmospheric water cycle dependeht of the existence of dimers. For in- on their vertical profiles. We find that gaseous stance, Chameides[1975] has argued that HNO3 HC1, HN03, and HBr are sufficiently soluble in should follow the water-vapor mixing ratio gradi- water to suggest that their vertical profiles in ent, based on the high solubility of the gas in the troposphere have a similar shape to that of liquid water. In this work, we generalize the water va•or. Thuswe predict that HC1,HN03, and moredetailed argumentsof Chameides[1975] and HBr exhibit a steep negative gradient with alti- suggest which species should exhibit this nega- tude roughly equal to the altitude gradient of tive gradient and which should not. -

Inelastic Scattering in Ocean Water and Its Impact on Trace Gas Retrievals from Satellite Data

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 3, 1365–1375, 2003 www.atmos-chem-phys.org/acp/3/1365/ Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Inelastic scattering in ocean water and its impact on trace gas retrievals from satellite data M. Vountas, A. Richter, F. Wittrock, and J. P. Burrows Institute for Environmental Physics, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany Received: 4 April 2003 – Published in Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss.: 2 June 2003 Revised: 29 August 2003 – Accepted: 4 September 2003 – Published: 15 September 2003 Abstract. Over clear ocean waters, photons scattered within 1 Introduction the water body contribute significantly to the upwelling flux. In addition to elastic scattering, inelastic Vibrational Raman Backscattered light from waters with low concentrations of Scattering (VRS) by liquid water is also playing a role and chlorophyll and gelbstoff – which are commonly referred can have a strong impact on the spectral distribution of the to as oligotrophic waters – is significantly influenced by outgoing radiance. Under clear-sky conditions, VRS has an Vibrational Raman Scattering (VRS) within the water (e.g. influence on trace gas retrievals from space-borne measure- Stavn and Weidemann, 1988; Marshall and Smith, 1990; ments of the backscattered radiance such as from e.g. GOME Haltrin and Kattawar, 1993; Sathyendranath and Platt, 1998; (Global Ozone Monitoring Experiment). The effect is par- Vasilkov et al., 2002b). ticularly important for geo-locations with small solar zenith As inelastic scattering redistributes photons over wave- angles and over waters with low chlorophyll concentration. length, VRS fills-in solar Fraunhofer lines, as well as trace gas absorption lines and therefore changes the spectral dis- In this study, a simple ocean reflectance model (Sathyen- tribution of scattered light in the atmosphere. -

Package 'Marelac'

Package ‘marelac’ February 20, 2020 Version 2.1.10 Title Tools for Aquatic Sciences Author Karline Soetaert [aut, cre], Thomas Petzoldt [aut], Filip Meysman [cph], Lorenz Meire [cph] Maintainer Karline Soetaert <[email protected]> Depends R (>= 3.2), shape Imports stats, seacarb Description Datasets, constants, conversion factors, and utilities for 'MArine', 'Riverine', 'Estuarine', 'LAcustrine' and 'Coastal' science. The package contains among others: (1) chemical and physical constants and datasets, e.g. atomic weights, gas constants, the earths bathymetry; (2) conversion factors (e.g. gram to mol to liter, barometric units, temperature, salinity); (3) physical functions, e.g. to estimate concentrations of conservative substances, gas transfer and diffusion coefficients, the Coriolis force and gravity; (4) thermophysical properties of the seawater, as from the UNESCO polynomial or from the more recent derivation based on a Gibbs function. License GPL (>= 2) LazyData yes Repository CRAN Repository/R-Forge/Project marelac Repository/R-Forge/Revision 205 Repository/R-Forge/DateTimeStamp 2020-02-11 22:10:45 Date/Publication 2020-02-20 18:50:04 UTC NeedsCompilation yes 1 2 R topics documented: R topics documented: marelac-package . .3 air_density . .5 air_spechum . .6 atmComp . .7 AtomicWeight . .8 Bathymetry . .9 Constants . 10 convert_p . 11 convert_RtoS . 11 convert_salinity . 13 convert_StoCl . 15 convert_StoR . 16 convert_T . 17 coriolis . 18 diffcoeff . 19 earth_surf . 21 gas_O2sat . 23 gas_satconc . 25 gas_schmidt . 27 gas_solubility . 28 gas_transfer . 31 gravity . 33 molvol . 34 molweight . 36 Oceans . 37 redfield . 38 ssd2rad . 39 sw_adtgrad . 40 sw_alpha . 41 sw_beta . 42 sw_comp . 43 sw_conserv . 44 sw_cp . 45 sw_dens . 47 sw_depth . 49 sw_enthalpy . 50 sw_entropy . 51 sw_gibbs . 52 sw_kappa . -

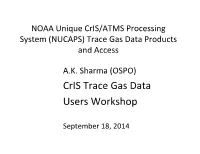

Cris Trace Gas Data Users Workshop

NOAA Unique CrIS/ATMS Processing System (NUCAPS) Trace Gas Data Products and Access A.K. Sharma (OSPO) CrIS Trace Gas Data Users Workshop September 18, 2014 The NOAA Unique CrIS/ATMS Processing System Products Retrieval Products gas Range Precisio d.o.f. Interfering Gases Science Cloud Cleared Radiances 660-750 cm-1 (cm-1) n Code 2200-2400 cm-1 T 650-800 1K/km 6-10 H2O,O3,N2O 100 levels Cloud fracon and Top 660-750 cm-1 2375-2395 emissivity Pressure Surface temperature window H2O 1200-1600 15% 4-6 CH4, HNO3 100 layers O 1025-1050 10% 1+ H2O,emissivity 100 layers Temperature 660-750 cm-1 3 2200-2400 cm-1 CO 2080-2200 15% ≈ 1 H2O,N2O 100 layers Water Vapor 780 – 1090 cm-1 1200-1750 cm-1 CH4 1250-1370 1.5% ≈ 1 H2O,HNO3,N2O 100 layers O3 990 – 1070 cm-1 CO2 680-795 0.5% ≈ 1 H2O,O3 100 layers CO 2155 – 2220 cm-1 2375-2395 T(p) CH4 1220-1350 cm-1 Volcanic 1340-1380 50% ?? < 1 H2O,HNO3 flag SO2 N2O 1290-1300cm-1 2190-2240cm-1 HNO3 860-920 50% ?? < 1 emissivity 100 layers 1320-1330 H2O,CH4,N2O HNO3 760-1320cm-1 N2O 1250-1315 5% ?? < 1 H2O 100 layers SO2 1343-1383cm-1 2180-2250 H2O,CO NH3 860-875 50% <1 emissivity BT diff CFCs 790-940 20-50% <1 emissivity Constant NUCAPS EDR Trace Gas Products The EDR product contains the following trace gas profiles calculated on each CrIS FOR: O3 layer column density (at 100 levels) O3 mixing ratio (at 100 levels) First Guess O3 layer column density (at 100 levels) First Guess O3 mixing ratio (at 100 levels) CH4 layer column density (at 100 levels) CH4 mixing ratio (at 100 levels) CO2 mixing ratio (at 100 levels) HNO3 layer column density (at 100 levels) HNO3 mixing ratio (at 100 levels) N2O layer column density (at 100 levels) N2O mixing ratio (at 100 levels) SO2 layer column density (at 100 levels) SO2 mixing ratio (at 100 levels) 3 AWIPS NUCAPS Products The retrieval product for AWIPS contains the following variaBles. -

Concentrations and Fluxes of Aerosol Particles During the LAPBIAT

Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss., 7, 709–751, 2007 Atmospheric www.atmos-chem-phys-discuss.net/7/709/2007/ Chemistry © Author(s) 2007. This work is licensed and Physics under a Creative Commons License. Discussions Concentrations and fluxes of aerosol particles during the LAPBIAT measurement campaign in Varri¨ o¨ field station T. M. Ruuskanen1, M. Kaasik2, P. P. Aalto1, U. Horrak˜ 2, M. Vana1,2, M. Martensson˚ 3, Y. J. Yoon4, P. Keronen1, G. Mordas1, D. Ceburnis4, E. D. Nilsson3, C. O’Dowd4, M. Noppel2, T. Alliksaar5, J. Ivask5, M. Sofiev6, M. Prank2, and M. Kulmala1 1University of Helsinki, Dept. of Physical Sciences, P.O. Box 64, 00014 University of Helsinki, Finland 2Institute of Environmental Physics, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia 3Department of Applied Environmental Science, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden 4Department of Experimental Physics, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland 5Institute of Geology, Tallinn University of Technology, Tallinn, Estonia 6Air Quality Research, Finnish Meteorological Institute, Finland Received: 21 November 2006 – Accepted: 8 January 2006 – Published: 17 January 2007 Correspondence to: T. M. Ruuskanen (taina.ruuskanen@helsinki.fi) 709 Abstract The LAPBIAT measurement campaign took place in the SMEAR I measurement station located in Eastern Lapland in the spring of 2003 between 26 April and 11 May. In this paper we describe the measurement campaign, concentrations and fluxes of aerosol 5 particles, air ions and trace gases, paying special attention to an aerosol particle for- mation event broken by a polluted air mass approaching from industrial areas of Kola Peninsula, Russia. Aerosol particle number flux measurements show strong downward fluxes during that time. -

Calculation Exercises with Answers and Solutions

Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Calculation Exercises Contents Exercise A, chapter 1 - 3 in Jacob …………………………………………………… 2 Exercise B, chapter 4, 6 in Jacob …………………………………………………… 6 Exercise C, chapter 7, 8 in Jacob, OH on aerosols and booklet by Heintzenberg … 11 Exercise D, chapter 9 in Jacob………………………………………………………. 16 Exercise E, chapter 10 in Jacob……………………………………………………… 20 Exercise F, chapter 11 - 13 in Jacob………………………………………………… 24 Answers and solutions …………………………………………………………………. 29 Note that approximately 40% of the written exam deals with calculations. The remainder is about understanding of the theory. Exercises marked with an asterisk (*) are for the most interested students. These exercises are more comprehensive and/or difficult than questions appearing in the written exam. 1 Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics – Exercise A, chap. 1 – 3 Recommended activity before exercise: Try to solve 1:1 – 1:5, 2:1 – 2:2 and 3:1 – 3:2. Summary: Concentration Example Advantage Number density No. molecules/m3, Useful for calculations of reaction kmol/m3 rates in the gas phase Partial pressure Useful measure on the amount of a substance that easily can be converted to mixing ratio Mixing ratio ppmv can mean e.g. Concentration relative to the mole/mole or partial concentration of air molecules. Very pressure/total pressure useful because air is compressible. Ideal gas law: PV = nRT Molar mass: M = m/n Density: ρ = m/V = PM/RT; (from the two equations above) Mixing ratio (vol): Cx = nx/na = Px/Pa ≠ mx/ma Number density: Cvol = nNav/V 26 -1 Avogadro’s -

Lecture 3. the Basic Properties of the Natural Atmosphere 1. Composition

Lecture 3. The basic properties of the natural atmosphere Objectives: 1. Composition of air. 2. Pressure. 3. Temperature. 4. Density. 5. Concentration. Mole. Mixing ratio. 6. Gas laws. 7. Dry air and moist air. Readings: Turco: p.11-27, 38-43, 366-367, 490-492; Brimblecombe: p. 1-5 1. Composition of air. The word atmosphere derives from the Greek atmo (vapor) and spherios (sphere). The Earth’s atmosphere is a mixture of gases that we call air. Air usually contains a number of small particles (atmospheric aerosols), clouds of condensed water, and ice cloud. NOTE : The atmosphere is a thin veil of gases; if our planet were the size of an apple, its atmosphere would be thick as the apple peel. Some 80% of the mass of the atmosphere is within 10 km of the surface of the Earth, which has a diameter of about 12,742 km. The Earth’s atmosphere as a mixture of gases is characterized by pressure, temperature, and density which vary with altitude (will be discussed in Lecture 4). The atmosphere below about 100 km is called Homosphere. This part of the atmosphere consists of uniform mixtures of gases as illustrated in Table 3.1. 1 Table 3.1. The composition of air. Gases Fraction of air Constant gases Nitrogen, N2 78.08% Oxygen, O2 20.95% Argon, Ar 0.93% Neon, Ne 0.0018% Helium, He 0.0005% Krypton, Kr 0.00011% Xenon, Xe 0.000009% Variable gases Water vapor, H2O 4.0% (maximum, in the tropics) 0.00001% (minimum, at the South Pole) Carbon dioxide, CO2 0.0365% (increasing ~0.4% per year) Methane, CH4 ~0.00018% (increases due to agriculture) Hydrogen, H2 ~0.00006% Nitrous oxide, N2O ~0.00003% Carbon monoxide, CO ~0.000009% Ozone, O3 ~0.000001% - 0.0004% Fluorocarbon 12, CF2Cl2 ~0.00000005% Other gases 1% Oxygen 21% Nitrogen 78% 2 • Some gases in Table 3.1 are called constant gases because the ratio of the number of molecules for each gas and the total number of molecules of air do not change substantially from time to time or place to place. -

Interactions Between Polymers and Nanoparticles : Formation of « Supermicellar » Hybrid Aggregates

1 Interactions between Polymers and Nanoparticles : Formation of « Supermicellar » Hybrid Aggregates J.-F. Berret@, K. Yokota* and M. Morvan, Complex Fluids Laboratory, UMR CNRS - Rhodia n°166, Cranbury Research Center Rhodia 259 Prospect Plains Road Cranbury NJ 08512 USA Abstract : When polyelectrolyte-neutral block copolymers are mixed in solutions to oppositely charged species (e.g. surfactant micelles, macromolecules, proteins etc…), there is the formation of stable “supermicellar” aggregates combining both components. The resulting colloidal complexes exhibit a core-shell structure and the mechanism yielding to their formation is electrostatic self-assembly. In this contribution, we report on the structural properties of “supermicellar” aggregates made from yttrium-based inorganic nanoparticles (radius 2 nm) and polyelectrolyte-neutral block copolymers in aqueous solutions. The yttrium hydroxyacetate particles were chosen as a model system for inorganic colloids, and also for their use in industrial applications as precursors for ceramic and opto-electronic materials. The copolymers placed under scrutiny are the water soluble and asymmetric poly(sodium acrylate)-b-poly(acrylamide) diblocks. Using static and dynamical light scattering experiments, we demonstrate the analogy between surfactant micelles and nanoparticles in the complexation phenomenon with oppositely charged polymers. We also determine the sizes and the aggregation numbers of the hybrid organic-inorganic 1 2 complexes. Several additional properties are discussed, such -

Dual Laser Trace Gas Monitor Sensitive, Rapid, Highly Specific and Continuous Measurements of Multiple Atmospheric Trace Gases in Ambient Air

Dual Laser Trace Gas Monitor Sensitive, rapid, highly specific and continuous measurements of multiple atmospheric trace gases in ambient air. APPLICATIONS ADVANTAGES • Extremely sensitive detection of a wide variety of • Absolute trace gas concentrations with atmospheric trace gases, such as: methane, out calibration gases. nitrous oxide, nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, formaldehyde, • Fast time response. formic acid, ethylene, acetylene, carbonyl sulfide, acrolein, ammonia and others. • Free from interferences by other atmospheric gases or water vapor. • Combustion monitoring and characterization. • Turnkey and unattended operation. • Isotopic monitoring of CH4 and N2O for source/ sink characterization. • Ready to be deployed in field measurements and on moving platforms. • Eddy Covariance measurements. • Two lasers allow simultaneous • Fast response plume studies. measurement of more species. • Air quality monitoring. • Optical pathlength of either 76 meters or 210 meters. • Mobile measurements from ship, truck, and Aircraft platforms. AERODYNE RESEARCH, Inc. 45 MANNING ROAD, BILLERICA, MA 01821 (978) 663 9500 www.aerodyne.com CAEC_TILDAS_DUAL POPULAR INSTRUMENTS HIGHER PRECISION AND ACCURACY IS OBTAINABLE WITH MID-INFRARED LASERS Clumped CO2 Isotopes* CH4 Isotopes CO2, Water Isotopes N2O Isotopes NO, NO2 CH4, N2O, CO,CO2, H2O, C2H6 MECHANICAL SPECIFICATIONS FOR DUAL LASER TRACE GAS MONITOR: Dimensions: 560 mm x 770 mm x 640 mm (W x D x H) Weight: 75 kg Electrical Power: 250-500 W, 120/240 V, 55/60 Hz (without pump) MULTIPASS CELL: Choice of 76 meter standard cell (V=0.5 liters) or 210 meter “Super Cell” (V=2liters) *Image attribution by Psammophile [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons REFERENCES: Nelson, D.D.