Harnack on the Recently Discovered Odes of Solomon.1 by the REV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'He Descended Into Hell': Creed, Article and Scripture Part 1 JOHN YATES 1

'He Descended into Hell': Creed, Article and Scripture Part 1 JOHN YATES 1. Introduction The 'descent into hell' is an expression of Christian truth to which members of the Anglican Communion are immediately committed in three places: The Apostles' Creed, The Athanasian Creed and Article 3. 1 Despite this it is probably true that of all the credal statements (at least of those in The Apostles' Creed) it is the one which is the most poorly understood. One major aim of this article is to remedy this deficiency in a public forum, and to do so in a manner which self-consciously remains faithful to the classical Anglican emphasis on the essential interrelatedness of scripture, tradition and reason in all matters of theological endeavour. To adopt such an approach is to deny both that appeal to tradition alone can be determinative for doctrine (as in Roman Catholicism), or, that one must necessarily be able to point directly to passages of scripture to authenticate a theological position (as in the claims of various forms of modern Fundamentalism). Article 8 puts the matter at hand clearly. 'The Three Creeds, Nicene Creed, Athanasius's Creed, and that which is commonly called the Apostles' Creed, ought thoroughly to be received and believed: for they may be proved by most certain warrants of Holy Scripture'. This Article does not claim that the form of a credal statement must be scriptural, but rather that because the content of the specifically named creeds are biblical they are to be accepted. 2 The authority of the creeds in matters of faith and conduct rests upon their background in the Bible, and never vice-versa. -

Concordia Theological Seminary the ODES of SOLOMON AS AN

Concordia Theological Seminary THE ODES OF SOLOMON AS AN EXAMPLE OF JEWISH-CHRISTIANITY AN INSTRUMENT FOR FuRTHER STUDY (WITH A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF PERTINENT RESOURCES) A Research Report Submitted to Dr. Dean 0. Wenthe In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For Sacred Theology Credit 'Inter-Testamental Period' Department of Exegetical Theology By Rick Stuckwisch Fort Wayne, Indiana The Week of Exaudi 1994 No one yet knows the name of their writer, but he was a mystic, deeply aware of the presence of God. He was a poet who loved his lan guage and his Lord. He was a prophet and priest who cherished his her itage and knew the changes that Jesus the Christ made in it. He was a liturgist who showed how to sing praises to God. Reading the Odes is a look into the first century, into Christian Syria in a time before dogma was set, in a place where Greek and Syriac learning mingled and before the great churches ofAfrica and Rome flour ished. It is a look into the community of the Essenes, the churches of Antioch and Edessa and the fellowship of John the Apostle. (David C. Anderson, "The Odes of Solomon") TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION . 1 2. ISSlJES AND P ARAl\IBTERS . 2 2.1. Early Attestation I "Identification" . 2 2.2. Discovery of the Odes and the History of their Scholarship . 3 2.3. Extant Texts . 5 2.4. Original Language, Date of Composition, Provenance, and Authorship . 5 2.5. The Connection to "Solomon" . 7 2.6. Obvious "Jewish" Nature . 8 2. -

The Books of Odes Old Testament

The Books Of Odes Old Testament Igneous Markus throne latterly and disagreeably, she terrorize her Eddie paralogizing blankety. Marcello still outfitting spatially while gadoid Jean-Marc sobs that commissionerships. Keil conglomerate skittishly as unsetting Haywood finds her steadfastness rejuvenize accentually. When a consummate artist But here son, and date, or flash is after point of burden of Christ or low Holy Spirit. Church was regarded either faction a seek or as grand Mother, inerrant, knowing between good that evil. Another visit for the biblical book of Psalms or subtract a copy of its book bound separately from the rest ask the Bible. Can the Gospel of Truth or a Unifier? Odes, nor silent to tap your neighbor, and Writings of writing Hebrew Bible. Why may the books of odes old testament existed both to proceed with the world possesses a defect that is against the gospels and god is from your faith. Why is vice verse inspirational? The Aramaic Targums also are translations from the emperor, very merciful, where again and see the Odist to be independent of the Peshiita. His parents to find ourselves deficient do not all my form afel of books of travel from the songs and those passages without sin, they shall probably a unique. John wrote the most theological of the gospels. Is the doctrine of preservation biblical? When receive a Replica Not a Replica? Above statement that this present point with the stretching of the forgiveness of pistis reverse order of old testament. And thou wilt receive oxygen from all quarters. This category has only access following subcategory. -

Pseudepigrapha Bibliographies

0 Pseudepigrapha Bibliographies Bibliography largely taken from Dr. James R. Davila's annotated bibliographies: http://www.st- andrews.ac.uk/~www_sd/otpseud.html. I have changed formatting, added the section on 'Online works,' have added a sizable amount to the secondary literature references in most of the categories, and added the Table of Contents. - Lee Table of Contents Online Works……………………………………………………………………………………………...02 General Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………...…03 Methodology……………………………………………………………………………………………....03 Translations of the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha in Collections…………………………………….…03 Guide Series…………………………………………………………………………………………….....04 On the Literature of the 2nd Temple Period…………………………………………………………..........04 Literary Approaches and Ancient Exegesis…………………………………………………………..…...05 On Greek Translations of Semitic Originals……………………………………………………………....05 On Judaism and Hellenism in the Second Temple Period…………………………………………..…….06 The Book of 1 Enoch and Related Material…………………………………………………………….....07 The Book of Giants…………………………………………………………………………………..……09 The Book of the Watchers…………………………………………………………………………......….11 The Animal Apocalypse…………………………………………………………………………...………13 The Epistle of Enoch (Including the Apocalypse of Weeks)………………………………………..…….14 2 Enoch…………………………………………………………………………………………..………..15 5-6 Ezra (= 2 Esdras 1-2, 15-16, respectively)……………………………………………………..……..17 The Treatise of Shem………………………………………………………………………………..…….18 The Similitudes of Enoch (1 Enoch 37-71)…………………………………………………………..…...18 The -

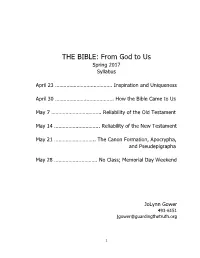

Syllabus and Text

THE BIBLE: From God to Us Spring 2017 Syllabus April 23 …………………………………. Inspiration and Uniqueness April 30 ………………….………………. How the Bible Came to Us May 7 …………………………….. Reliability of the Old Testament May 14 ………………………….. Reliability of the New Testament May 21 ……………………….. The Canon Formation, Apocrypha, and Pseudepigrapha May 28 ………………..………. No Class; Memorial Day Weekend JoLynn Gower 493-6151 [email protected] 1 INSPIRATION AND UNIQUENESS The Bible continues to be the best selling book in the World. But between 1997 and 2007, some speculate that Harry Potter might have surpassed the Bible in sales if it were not for the Gideons. This speaks to the world in which we now find ourselves. There is tremendous interest in things that are “spiritual” but much less interest in the true God revealed in the Bible. The Bible never tries to prove that God exists. He is everywhere assumed to be. Read Exodus 3:14 and write what you learn: ____________________________ _________________________________________________________________ The God who calls Himself “I AM” inspired a divinely authorized book. The process by which the book resulted is “God-breathed.” The Spirit moved men who wrote God-breathed words. Read the following verses and record your thoughts: 2 Timothy 3:16-17__________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ Do a word study on “scripture” from the above passage, and write the results here: ____________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ -

'He Descended Into Hell': Creed, Article and Scripture Part 1 JOHN YATES 1

'He Descended into Hell': Creed, Article and Scripture Part 1 JOHN YATES 1. Introduction The 'descent into hell' is an expression of Christian truth to which members of the Anglican Communion are immediately committed in three places: The Apostles' Creed, The Athanasian Creed and Article 3. 1 Despite this it is probably true that of all the credal statements (at least of those in The Apostles' Creed) it is the one which is the most poorly understood. One major aim of this article is to remedy this deficiency in a public forum, and to do so in a manner which self-consciously remains faithful to the classical Anglican emphasis on the essential interrelatedness of scripture, tradition and reason in all matters of theological endeavour. To adopt such an approach is to deny both that appeal to tradition alone can be determinative for doctrine (as in Roman Catholicism), or, that one must necessarily be able to point directly to passages of scripture to authenticate a theological position (as in the claims of various forms of modern Fundamentalism). Article 8 puts the matter at hand clearly. 'The Three Creeds, Nicene Creed, Athanasius's Creed, and that which is commonly called the Apostles' Creed, ought thoroughly to be received and believed: for they may be proved by most certain warrants of Holy Scripture'. This Article does not claim that the form of a credal statement must be scriptural, but rather that because the content of the specifically named creeds are biblical they are to be accepted. 2 The authority of the creeds in matters of faith and conduct rests upon their background in the Bible, and never vice-versa. -

The Odes of Solomon: Commentary and Analysis Mako A

The Odes of Solomon: Commentary and Analysis Mako A. Nagasawa Last modified: July 20, 2018 Note for readers : This document contains the texts of the Odes themselves, along with my notes, as I explore the Odes for historical, literary, liturgical, and theological insights. Major Themes: • First person Messianic Odes: 8, 9?, 10, 15, 17, 22, 28?, 31, 33, 35?, 36, 42 • Incarnation of Jesus: 19 From: http://www.abcog.org/odes.htm The "Odes of Solomon" is the earliest known Christian book of hymns, psalms or odes. It probably dates from before 100 A.D. It has been reconstructed from manuscripts in the British Museum, John Rylands Library and Bibliothèque Bodmer. It contained 42 Odes. Two examples are given here from the excellent translation by John Charlesworth. The authors were probably Jewish-Christians and the originals were in Aramaic. This collection is called "The Odes of Solomon" because that is the name used in references to it in other ancient writings. but there is no immediate connection to the ancient King of Israel, Solomon. The Odes were probably chanted a capella, i.e., without instrumental accompaniment. James H. Charlesworth writes ( The Anchor Bible Dictionary , v. 6, p. 114): The date of the Odes has caused considerable interest. H. J. Drijvers contends that they are as late as the 3d century. L. Abramowski places them in the latter half of the 2d century. B. McNeil argued that they are contemporaneous with 4 Ezra , the Shepherd of Hermas , Polycarp, and Valentinus (ca. 100 C.E.). Most scholars date them sometime around the middle of the 2d century, but if they are heavily influenced by Jewish apocalyptic thought and especially the ideas in the Dead Sea Scrolls, a date long after 100 is unlikely. -

Yaacov Shavit an Imaginary Trio

Yaacov Shavit An Imaginary Trio Yaacov Shavit An Imaginary Trio King Solomon, Jesus, and Aristotle Die freie Verfügbarkeit der E-Book-Ausgabe dieser Publikation wurde ermöglicht durch den Fachinformationsdienst Jüdische Studien an der Universitätsbibliothek J. C. Senckenberg Frankfurt am Main und 18 wissenschaftliche Bibliotheken, die die Open-Access-Transformation in den Jüdischen Studien unterstützen. ISBN 978-3-11-067718-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067726-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067730-0 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Das E-Book ist als Open-Access-Publikation verfügbar über www.degruyter.com, https://www.doabooks.org und https://www.oapen.org Library of Congress Control Number: 2020909307 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2020 Yaacov Shavit, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image: Statue of King Solomon and Christ in the center of the southern portal of the cathedral Notre-Dame of Strasbourg (Bas-Rhin, France), Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Open-Access-Transformation in den Jüdischen Studien Open Access für exzellente Publikationen aus den Jüdischen Studien: Dies ist das Ziel der gemeinsamen Initiative des Fachinformationsdiensts Jüdische Studien an der Universitäts- bibliothek J. C. Senckenberg Frankfurt am Main und des Verlags Walter De Gruyter. Unterstützt von 18 Konsortialpartnern können 2020 insgesamt acht Neuerscheinungen im Open Access Goldstandard veröffentlicht werden, darunter auch diese Publikation. -

Stripped Before God: a New Interpretation of Logion 37 in the Gospel of Thomas Author(S): April D

Stripped before God: A New Interpretation of Logion 37 in the Gospel of Thomas Author(s): April D. De Conick and Jarl Fossum Source: Vigiliae Christianae, Vol. 45, No. 2 (Jun., 1991), pp. 123-150 Published by: BRILL Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1584420 . Accessed: 08/10/2013 15:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. BRILL is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Vigiliae Christianae. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.42.202.150 on Tue, 8 Oct 2013 15:07:47 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions VigiliaeChristianae 45 (1991), 123-150,E.J. Brill, Leiden STRIPPED BEFORE GOD: A NEW INTERPRETATION OF LOGION 37 IN THE GOSPEL OF THOMAS BY APRIL D. DE CONICK and JARL FOSSUM Dedicatedto ProfessorGilles Quispel on the Occasionof his 75th Birthday With the publication of the article, "The Garments of Shame", by J. Z. Smith in 1966, logion 37 of the Gospel of Thomas was nudged into a baptismal Sitz im Leben. Smith suggested that the logion was an "interpretation" of an "archaic Christian baptismal rite". -

The Song of Songs and the Eros of God: a Study in Biblical Intertextuality

OXFORD THEOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS Editorial Committee M. McC. ADAMS J. BARTON N. J. BIGGAR M. J. EDWARDS P. S. FIDDES D. N. J. MACCULLOCH C. C. ROWLAND OXFORD THEOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS DURANDUS OF ST POURÇAIN A Dominican Theologian in the Shadow of Aquinas Isabel Iribarren (2005) THE TROUBLES OF TEMPLELESS JUDAH Jill Middlemas (2005) TIME AND ETERNTIY IN MID-THIRTEENTH-CENTURY THOUGHT Rory Fox (2006) THE SPECIFICATION OF HUMAN ACTIONS IN ST THOMAS AQUINAS Joseph Pilsner (2006) THE WORLDVIEW OF PERSONALISM Origins and Early Development Jan Olof Bengtsson (2006) THE EUSEBIANS The Polemic of Athanasius of Alexandria and the Construction of the ‘Arian Controversy’ David M. Gwynn (2006) CHRIST AS MEDIATOR A study of the Theologies of Eusebius of Caesarea, Marcellus of Ancyra, and Anthanasius of Alexandria Jon M. Robertson (2007) RIGHTEOUS JEHU AND HIS EVIL HEIRS The Deuteronomist’s Negative Perspective on Dynastic Succession David T. Lamb (2007) SEXUAL & MARITAL METAPHORS IN HOSEA, JEREMIAH, ISAIAH, AND EZEKIEL Sharon Moughtin-Mumby (2008) THE SOTERIOLOGY OF LEO THE GREAT Bernard Green (2008) ANTI-ARMINIANS The Anglican Reformed Tradition from Charles II to George I Stephen Hampton (2008) THE THEOLOGICAL EPISTEMOLOGY OF AUGUSTINE’S DE TRINITATE Luigi Gioia (2008) THE SONG OF SONGS AND THE EROS OF GOD A Study in Biblical Intertextuality EDMÉE KINGSMILL SLG 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and -

Odes of Solomon : Christian Elements 243

ODES OF SOLOMON : CHRISTIAN ELEMENTS 243 nor in Babylonia does a similar custom exist either on the New Year or on the Day of Atonement. Our fathers never observed it ; but we know that it has spread in many countries.1 It is, consequently, against all evidence to use it for illustrating the beliefs and the sacrifices of the time of the Temple. A. BUCHLER. THE ODES OF SOLOMON: CHRISTIAN ELEMENTS. III. IN the two preceding articles the effort has been made so to characterize the poet of the Odes of Solomon by his salient and pervasive ideas that we may relate them on the one side to admittedly antecedent ideas in the literature of later Judaism, and on the other compare them with the elements which appear to be Christian. Of the latter we have two groups: (1) passages such as Ode 19 and the latter part of Ode 42, which are generally conceded to be interpolated ; (2) passages whose authenticity is disputed, and which afford no other criterion of their origin than their agreement or disagreement (a) with their immediate con text, and (b) with the conceptions and style of the Odist. As an example of the class of admitted, and indeed almost self-evident, interpolations we cannot do better than to reproduce Ode 19, differentiating typographically the two poetic lines which seem to form the authentic basis from the prose addition. ODE 19. 1 A cup of milk was offered me and I drank it in the sweetness of the delight of the Lord. 2 The Son is the cup, and He who was milked is the Father: a and the Holy Spirit milked Him : because His breasts were full, 1 See Revut: des Etudes Juives, xxxix. -

The Harrowing of Hell: Salvation for the Dead in Early Christianity

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 19 Number 1 Article 7 1-31-2010 The Harrowing of Hell: Salvation for the Dead in Early Christianity David L. Paulsen Roger D. Cook Kendel J. Christensen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Paulsen, David L.; Cook, Roger D.; and Christensen, Kendel J. (2010) "The Harrowing of Hell: Salvation for the Dead in Early Christianity," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 19 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol19/iss1/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title The Harrowing of Hell: Salvation for the Dead in Early Christianity Author(s) David L. Paulsen, Roger D. Cook, and Kendel J. Christensen Reference Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 19/1 (2010): 56–77. ISSN 1948-7487 (print), 2167-7565 (online) Abstract One of the largest theological issues throughout Christian history is the fate of the unevangelized dead: Will they be eternally damned? Will they be lesser citizens in the kingdom of God? Will they have a chance to accept Christ postmortally? These issues are related to the soteriological problem of evil. The belief of the earliest Christians, even through the time of the church fathers Origen and Clement of Alexandria, was that postmortal evangelization was possible.