John Smith: a Charismatic and Transformational Religious Leader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Story – Monday 13 November, 8Pm, ABC and ABC Iview BEHIND the MASK – MIKE WILLESEE, PART TWO

RELEASED: Thursday 9 November, 2017 Australian Story – Monday 13 November, 8pm, ABC and ABC iview BEHIND THE MASK – MIKE WILLESEE, PART TWO Introduced by Ray Martin. The conclusion to Australian Story’s two-part exclusive on current affairs legend Mike Willesee as he faces the fight of his life – a cancer diagnosis. The episode begins in 1993 when Mike returned to A Current Affair for a year, conducting some of his most memorable interviews. He drew wide praise for an interview with opposition leader John Hewson, during which the prime ministerial hopeful tied himself in knots over a question about the GST. Many considered it the moment Hewson lost the election. Four weeks later praise turned to condemnation when Mike interviewed two young children held captive by killers during the Cangai siege. “I think this is a classic case where we misjudged the audience reaction,” admits former Nine news chief Peter Meakin. Tiring of nightly current affairs, Mike turned his attention to a variety of business interests and documentary making. While in Kenya on his way to film in Sudan he had a premonition that the small plane he was boarding would crash. Shortly after take-off, it did. Although Mike was unhurt, the experience had a profound impact on him and led him on a long journey back to the Catholic faith of his childhood. In the years since he has invested much of his time into trying to find scientific proof for various religious miracles. It is Mike’s strong religious faith, along with the support of his family, that has helped him since being diagnosed with cancer in October last year. -

Australian Story – Monday 6 November, 8Pm, ABC and ABC Iview BEHIND the MASK – MIKE WILLESEE

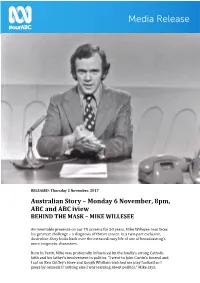

RELEASED: Thursday 2 November, 2017 Australian Story – Monday 6 November, 8pm, ABC and ABC iview BEHIND THE MASK – MIKE WILLESEE An inimitable presence on our TV screens for 50 years, Mike Willesee now faces his greatest challenge – a diagnosis of throat cancer. In a two-part exclusive, Australian Story looks back over the extraordinary life of one of broadcasting’s more enigmatic characters. Born in Perth, Mike was profoundly influenced by the family’s strong Catholic faith and his father’s involvement in politics. “I went to John Curtin’s funeral and I sat on Ben Chifley’s knee and Gough Whitlam watched me play football so I guess by osmosis if nothing else I was learning about politics,” Mike says. As a 10-year-old, Mike was sent briefly to the notorious Bindoon Boy’s Town by his father in order to toughen him up. It was a brutal experience. “I still don't know why my father thought I needed to toughen up,” Mike says, “but I did toughen up. You know, it changed me.” Later, a split within the Labor party saw the family ostracised by the Catholic church. His father was railed against from the pulpit and Mike was forced out of school a year early by the Catholic brothers who taught him. These events, and an emerging interest in girls, saw Mike turn his back on the church. After school, Mike fell into journalism, working for papers in Perth and Melbourne before ending up in Canberra. When the ABC launched the ground- breaking current affairs program This Day Tonight, he found himself in the right place at the right time. -

Lobby Loyde: the G.O.D.Father of Australian Rock

Lobby Loyde: the G.O.D.father of Australian rock Paul Oldham Supervisor: Dr Vicki Crowley A thesis submitted to The University of South Australia Bachelor of Arts (Honours) School of Communication, International Studies and Languages Division of Education, Arts, and Social Science Contents Lobby Loyde: the G.O.D.father of Australian rock ................................................. i Contents ................................................................................................................................... ii Table of Figures ................................................................................................................... iv Abstract .................................................................................................................................. ivi Statement of Authorship ............................................................................................... viiiii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. ix Chapter One: Overture ....................................................................................................... 1 Introduction: Lobby Loyde 1941 - 2007 ....................................................................... 2 It is written: The dominant narrative of Australian rock formation...................... 4 Oz Rock, Billy Thorpe and AC/DC ............................................................................... 7 Private eye: Looking for Lobby Loyde ......................................................................... -

Popular Music, Stars and Stardom

POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM EDITED BY STEPHEN LOY, JULIE RICKWOOD AND SAMANTHA BENNETT Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN (print): 9781760462123 ISBN (online): 9781760462130 WorldCat (print): 1039732304 WorldCat (online): 1039731982 DOI: 10.22459/PMSS.06.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design by Fiona Edge and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2018 ANU Press All chapters in this collection have been subjected to a double-blind peer-review process, as well as further reviewing at manuscript stage. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Contributors . ix 1 . Popular Music, Stars and Stardom: Definitions, Discourses, Interpretations . 1 Stephen Loy, Julie Rickwood and Samantha Bennett 2 . Interstellar Songwriting: What Propels a Song Beyond Escape Velocity? . 21 Clive Harrison 3 . A Good Black Music Story? Black American Stars in Australian Musical Entertainment Before ‘Jazz’ . 37 John Whiteoak 4 . ‘You’re Messin’ Up My Mind’: Why Judy Jacques Avoided the Path of the Pop Diva . 55 Robin Ryan 5 . Wendy Saddington: Beyond an ‘Underground Icon’ . 73 Julie Rickwood 6 . Unsung Heroes: Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown’s Funk Brothers . 95 Vincent Perry 7 . When Divas and Rock Stars Collide: Interpreting Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballé’s Barcelona . -

BB-1971-12-25-II-Tal

0000000000000000000000000000 000000.00W M0( 4'' .................111111111111 .............1111111111 0 0 o 041111%.* I I www.americanradiohistory.com TOP Cartridge TV ifape FCC Extends Radiation Cartridges Limits Discussion Time (Based on Best Selling LP's) By MILDRED HALL Eke Last Week Week Title, Artist, Label (Dgllcater) (a-Tr. B Cassette Nos.) WASHINGTON-More requests for extension of because some of the home video tuners will utilize time to comment on the government's rulemaking on unused TV channels, and CATV people fear conflict 1 1 THERE'S A RIOT GOIN' ON cartridge tv radiation limits may bring another two- with their own increasing channel capacities, from 12 Sly & the Family Stone, Epic (EA 30986; ET 30986) month delay in comment deadline. Also, the Federal to 20 and more. 2 2 LED ZEPPELIN Communications Commission is considering a spin- Cable TV says the situation is "further complicated Atlantic (Ampex M87208; MS57208) off of the radiated -signal CTV devices for separate by the fact that there is a direct connection to the 3 8 MUSIC consideration. subscriber's TV set from the cable system to other Carole King, Ode (MM) (8T 77013; CS 77013) In response to a request by Dell-Star Corp., which subscribers." Any interference factor would be mul- 4 4 TEASER & THE FIRECAT roposes a "wireless" or "radiated signal" type system, tiplied over a whole network of CATV homes wired Cat Stevens, ABM (8T 4313; CS 4313) the FCC granted an extension to Dec. 17 for com- to a master antenna. was 5 5 AT CARNEGIE HALL ments, and to Dec. -

Australian Broadcasting Tribunal Annual Report 1981-82 Annual Report Australian Broadcasting Tribunal 1981-82

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL ANNUAL REPORT 1981-82 ANNUAL REPORT AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL 1981-82 Australian Government Publishing Service Canberra 1982 © Commonwealth of Australia 1982 ISSN 0728-606X Printed by Canberra Publishing & Printing Co .. Fyshwick. A.C.T. 2609 The Honourable the Minister for Communications In conformity with the provisions of section 28 of the Broadcasting and Television Act 1942, as amended, I have pleasure in presenting the Annual Report of the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal for the period l July 1981 to 30 June 1982. David Jones Chairman iii CONTENTS PART/ INTRODUCTION Page Legislation 1 Functions of the Tribunal 1 Membership of the Tribunal 1 Meetings of the Tribunal 2 Addresses given by Tribunal Members and Staff 2 Organisation and Staff of the Tribunal 4 Location of the Tribunal's Offices 4 Overseas Visits 5 Financial Accounts of the Tribunal 5 PART II GENERAL Broadcasting and Television Services in operation since 1953 6 Financial results - commercial broadcasting and television stations 7 Fees for licences for commercial broadcasting and television stations 10 Broadcasting and Televising of political matter 13 Political advertising 15 Administration of Section 116(4) of the Act 16 Complaints about programs and advertising 18 Appeals or reviews of Tribunal Decisions and actions by Commonwealth 20 Ombudsman, AdministrativeReview Council and Administrative Appeals Tribunal Reference of questions of law to the Federal Court of Australia pursuant 21 to Section 22B of the Act PART III PUBLIC INQUIRIES -

College of Arts, Education and Social Sciences Inaugural Research Conference

Papers presented at the COLLEGE OF ARTS, EDUCATION AND SOCIAL SCIENCES INAUGURAL RESEARCH CONFERENCE Scholarship and Community University of Western Sydney Bankstown campus 7 to 9 October 2005 ISBN 1 74108 127 0 Scholarship and Community was the theme of the inaugural research conference for the College of Arts, Education and Social Sciences. It was chosen to entice broad participation from all College disciplines as an enabler to thinking about the nexus between research and community. The conference also aimed to enhance the perception of College’s research culture and ambience as part of the postgraduate experience. It included keynote addresses from national and international scholars; symposia and workshops; and the presentation of music, sound art and video. Of the 150 papers presented, 68 were blind peer refereed and are included in this publication. The majority of the papers were written by Higher Degree Research candidates of the University. Other than adhering to submission guidelines and publication style and formatting, the papers have mostly been edited and corrected by their authors in consultation with colleagues, supervisors and peers. This publication highlights the diverse and interdisciplinary focus of the College’s research activities. I commend all the papers to you. Professor Michael Atherton Associate Dean (Research) Editor NB: All papers within these conference proceedings have been blind peer refereed. PAPERS Papers are listed by author alphabetically. Father-infant interaction: A review of current research. Brooke Adam, Stephen Malloch, Rudi Črnčec & Ben Bradley Brooke Adam, Hons Psych (1st Class) 2004 – Title ‘Here’s Looking at You! Eye gaze and Social Interaction of Nine-Month-Old Infants in Trios’. -

Impactos Turísticos-Económicos Y Socio-Culturales De Los Festivales

Impactos turísticos-económico y socio-culturales de los Festivales Musicales en la Comunidad Valenciana Laura Pérez Platero Impactos turístico-económicos y socioculturales de los festivales musicales en la Comunidad Valenciana Universidad de Alicante Departamento de Sociología I Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales IMPACTOS TURÍSTICO-ECONÓMICOS Y SOCIO-CULTURALES DE LOS FESTIVALES MUSICALES EN LA COMUNIDAD VALENCIANA Laura Pérez Platero Tesis presentada para aspirar al grado de DOCTOR POR LA UNIVERSIDAD DE ALICANTE Programa de doctorado: SOCIOLOGÍA: SOCIEDAD Y CULTURA CONTEMPORÁNEAS Dirigida por: Dr. Tomás Mazón Martínez: Profesor titular de Universidad I Impactos turístico-económicos y socioculturales de los festivales musicales en la Comunidad Valenciana II Impactos turístico-económicos y socioculturales de los festivales musicales en la Comunidad Valenciana “En verdad, si no fuera por la música, habría más razones para volverse loco” Piotr Ilich Tchaikovski (1840-1893) III Impactos turístico-económicos y socioculturales de los festivales musicales en la Comunidad Valenciana IV Impactos turístico-económicos y socioculturales de los festivales musicales en la Comunidad Valenciana AGRADECIMIENTOS Después del gran esfuerzo y dedicación que ha supuesto la realización de esta tesis, es inevitable estar agradecida a las personas que directa o indirectamente han participado en ella. En primer lugar, a mi director de tesis, Tomás Mazón, por creer en mí, acompañarme, aconsejarme, guiarme y alentarme. Su experiencia y dedicación han sido mi fuente de inspiración. A todas y cada una de las personas que se prestaron para ser entrevistadas y cuyos conocimientos y opiniones han hecho posible esta tesis. A Ester y Yolanda por su amistad y paciencia en mis momentos más bajos. -

Australia: a Cultural History (Third Edition)

AUSTRALIA A CULTURAL HISTORY THIRD EDITION JOHN RICKARD AUSTRALIA Australia A CULTURAL HISTORY Third Edition John Rickard Australia: A Cultural History (Third Edition) © Copyright 2017 John Rickard All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/ach-9781921867606.html Series: Australian History Series Editor: Sean Scalmer Design: Les Thomas Cover image: Aboriginal demonstrators protesting at the re-enactment of the First Fleet. The tall ships enter Sydney Harbour with the Harbour Bridge in the background on 26 January 1988 during the Bicentenary celebrations. Published in Sydney Morning Herald 26 January, 1988. Courtesy Fairfax Media Syndication, image FXJ24142. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Creator: Rickard, John, author. Title: Australia : a cultural history / John Rickard. Edition: Third Edition ISBN: 9781921867606 (paperback) Subjects: Australia--History. Australia--Civilization. Australia--Social conditions. ISBN (print): 9781921867606 ISBN (PDF): 9781921867613 First published 1988 Second edition 1996 In memory of John and Juan ABOUT THE AUTHOR John Rickard is the author of two prize-winning books, Class and Politics: New South Wales, Victoria and the Early Commonwealth, 1890-1910 and H.B. -

NEWMEDIA Greig ‘Boldy’ Bolderrow, 103.5 Mix FM (103.5 Triple Postal Address: M)/ 101.9 Sea FM (Now Hit 101.9) GM, Has Retired from Brisbane Radio

Volume 29. No 9 Jocks’ Journal May 1-16,2017 “Australia’s longest running radio industry publication” ‘Boldy’ Bows Out Of Radio NEWMEDIA Greig ‘Boldy’ Bolderrow, 103.5 Mix FM (103.5 Triple Postal Address: M)/ 101.9 Sea FM (now Hit 101.9) GM, has retired from Brisbane radio. His final day was on March 31. Greig began PO Box 2363 his career as a teenage announcer but he will be best Mansfield BC Qld 4122 remembered for his 33 years as General Manager for Web Address: Southern Cross Austereo in Wide Bay. The day after www.newmedia.com.au he finished his final exam he started his job at the Email: radio station. He had worked a lot of jobs throughout [email protected] the station before becoming the general manager. He started out as an announcer at night. After that he Phone Contacts: worked on breakfast shows and sales, all before he Office: (07) 3422 1374 became the general manager.” He managed Mix and Mobile: 0407 750 694 Sea in Maryborough and 93.1 Sea FM in Bundaberg, as well as several television channels. He says that supporting community organisations was the best part of the job. Radio News The brand new Bundy breakfast Karen-Louise Allen has left show has kicked off on Hitz939. ARN Sydney. She is moving Tim Aquilina, Assistant Matthew Ambrose made the to Macquarie Media in the Content Director of EON move north from Magic FM, role of Direct Sales Manager, Broadcasters, is leaving the Port Augusta teaming up with Sydney. -

Popular Music, Stars and Stardom

POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM EDITED BY STEPHEN LOY, JULIE RICKWOOD AND SAMANTHA BENNETT Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN (print): 9781760462123 ISBN (online): 9781760462130 WorldCat (print): 1039732304 WorldCat (online): 1039731982 DOI: 10.22459/PMSS.06.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design by Fiona Edge and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2018 ANU Press All chapters in this collection have been subjected to a double-blind peer-review process, as well as further reviewing at manuscript stage. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Contributors . ix 1 . Popular Music, Stars and Stardom: Definitions, Discourses, Interpretations . 1 Stephen Loy, Julie Rickwood and Samantha Bennett 2 . Interstellar Songwriting: What Propels a Song Beyond Escape Velocity? . 21 Clive Harrison 3 . A Good Black Music Story? Black American Stars in Australian Musical Entertainment Before ‘Jazz’ . 37 John Whiteoak 4 . ‘You’re Messin’ Up My Mind’: Why Judy Jacques Avoided the Path of the Pop Diva . 55 Robin Ryan 5 . Wendy Saddington: Beyond an ‘Underground Icon’ . 73 Julie Rickwood 6 . Unsung Heroes: Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown’s Funk Brothers . 95 Vincent Perry 7 . When Divas and Rock Stars Collide: Interpreting Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballé’s Barcelona . -

The Living Daylights 2(3) 22 January 1974 Richard Neville Editor

University of Wollongong Research Online The Living Daylights Historical & Cultural Collections 1-22-1974 The Living Daylights 2(3) 22 January 1974 Richard Neville Editor Follow this and additional works at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/livingdaylights Recommended Citation Neville, Richard, (1974), The Living Daylights 2(3) 22 January 1974, Incorporated Newsagencies Company, Melbourne, vol.2 no.3, January 22 - 28, 28p. http://ro.uow.edu.au/livingdaylights/13 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The Living Daylights 2(3) 22 January 1974 Publisher Incorporated Newsagencies Company, Melbourne, vol.2 no.3, January 22 - 28, 28p This serial is available at Research Online: http://ro.uow.edu.au/livingdaylights/13 Vol.2 No.3 Jan.22-28 1974 S CREW IN 6 T HE PETRO L GIAN TS «. A ballsy interview with oil maverick Ian Sykes BLACK & PROUD & ABOUT TO BE LYNCHED... In death row with Michael X WHAT S ON in Sydney & Melbourne (plus Sunbury details) a OLLOWING our US bases feature F last fortnight, there have been sev eral repercussions, the least important of which was the front page o f Melbourne’s Truth, sat, jan 19. n t n j l f As the source o f Truth's hallucinations (“ BLOOD WILL FLOW” ), we were cited as a “ left wing newspaper” (ha ha marx- ists) and credited with a variety o f dast ardly intentions. We would like to thank Truth for publicising the march on the US bases, leaving Melbourne early in may Richard Beckett and driving through the other major cities.